Many college students and their families are concerned about the high costs of textbooks. A company called Flat World Knowledge both gives away and sells open-source textbooks in a way it believes to be financially sustainable. This article reports on the financial sustainability of the Flat World Knowledge open-source textbook model after one year of operation.

Keywords: Open educational resources; open textbooks; electronic textbooks; Flat World Knowledge; open access; sustainability

Money is tight for college students in any economy, but during difficult economic times students work harder than ever to reduce expenses. One of the key expenses students face is the price of textbooks. The National Association of College Stores (2009) estimates that the average student in the United States spends $702 on textbooks per year. In total, students in the United States spend $5.5 billion each year on required textbooks—and this includes only purchases made at on-campus bookstores (National Association of College Stores, 2009).

Whether or not e-books can solve the problem of high textbook costs is still open to debate (Butler, 2009; Albanese, 2009). Many companies are rushing forward to distribute electronic textbooks that are substantially cheaper than printed copies. There has been a consistent hype stating that e-book sales will eclipse those of print books (Nelson, 2008), and this happened for the first time on Amazon.com on Christmas Day of 2009 (Allen, 2009). While the rising prominence of e-books in general (e.g., Amazon’s Kindle, Apple iBooks, and the Google Bookstore) may indicate a growing opportunity for electronic textbooks, e-books are hampered by some disadvantages. For example, digital rights management technologies prevent some e-books from being downloaded or used on multiple computers, and it is difficult or impossible to resell an e-book (Foster, 2005).

From a student’s perspective, the most attractive textbook would likely be a free one. Hilton and Wiley (2010) discuss a variety of organizations that make free digital textbooks available to college students. In some cases, government initiatives are sponsoring projects to make digital textbooks available to students for free or at a low cost. For example, the U.S. state of Washington has an initiative that would cap the cost of classroom materials at $30.00 per class (Overland, 2011). The United States Department of Labor has also announced grants that could be used to fund open-textbook projects (Gonzalez, 2011).

In other cases, for-profit and non-profit organizations are working to make free digital textbooks available. Because these organizations provide their textbooks for free, their long-term financial sustainability is an issue. Hilton and Wiley (2010) provide background on some of these organizations. Multiple authors have presented information about the sustainability of open educational resources in general (Downes, 2007; Koohang & Harman, 2007; Wiley, 2006). The present study focuses on the financial sustainability of one for-profit company that produces free and openly licensed textbooks: Flat World Knowledge.

Established in 2007, Flat World Knowledge (FWK) is trying to build a sustainable business based on open textbooks (i.e., textbooks licensed with a Creative Commons license). According to the FWK model, an expert author writes a textbook and receives editorial and design support from FWK. The finished book is made available online for free access under a Creative Commons Attribution, Noncommercial, Share Alike license (BY-NC-SA, Creative Commons, n.d.). Alternate formats of the book (such as printed and audio versions) as well as supplemental materials are created and made available for purchase. Hilton and Wiley (2010) provide additional detail about the FWK model and outline a variety of ways that FWK believes its pro-openness stance is educationally beneficial, including allowing professors to remix textbook content more easily (and legally) and offering students a free digital option for their required textbooks.

Hilton and Wiley (2010) examined the results of FWK’s alpha and beta tests. During alpha testing, a majority of surveyed faculty members and students expressed interest in the FWK open approach. For the beta test, FWK made six of their textbooks available to students in 27 different classes. In total, approximately 750 students enrolled in these classes. Each of these students had access to the free online version of the textbook and no purchase was required. Of these 750 students, 442 (59%) placed at least one order with FWK, with the average student spending $28.20. Approximately 40% of students chose to purchase a print copy of the textbook even though the online version was available for free (printed books were sold from the same site where the free version was available).

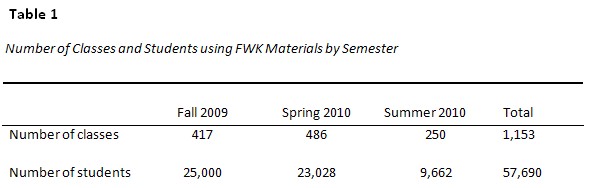

Flat World Knowledge left beta status and began allowing public adoptions of their textbooks at the start of the 2009–2010 school year. What follows is data gathered by the authors from FWK’s internal reporting and e-commerce systems. 57,690 students in 1,153 different classes used FWK textbooks during the first year the company was open to the public (10 textbooks were available at the time of this study). These classes occurred in three semesters: fall 2009, spring 2010, and summer 2010. Table 1 shows the number of classes participating and the number of students enrolled for each of these semesters.

Students in these classes could access their textbook in a variety of ways. They could (1) buy a print copy of the book from their local university bookstore or from an online site such as Amazon.com; (2) buy a complete print, PDF, or audio version of the text directly from FWK; (3) buy specific chapters, but not the whole book, from FWK; or (4) access the textbook online for free.

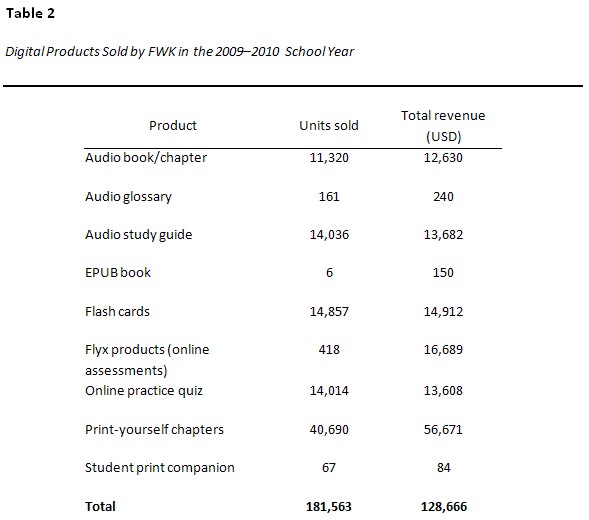

A total of 16,461 print textbooks were purchased over the three semesters, generating $479,259 of revenue. Of these print copies, 10,970 (67%) were purchased through a campus bookstore. In total, approximately 29% of students purchased a print copy of the textbook. In addition to these print textbook purchases, many students purchased digital products directly from FWK. Table 2 shows the number of additional products purchased as well as the revenue associated with these products.

65.7% of students taking a class that used FWK materials registered on the FWK website. Approximately one in four of the students who registered on the site made a purchase there. The average buyer made 1.3 purchases, with the average purchase totaling $30.89. Because many of these purchases were collections of resources bundled together the number of total unit purchases (181,563) is much higher than the average number of purchases.

FWK published its first 10 textbooks at an average cost of approximately $150,000 per book. Since these first 10 books were published, the average cost of producing a book has decreased to $120,000 per book due to increases in operational efficiencies. Broken down, those new costs are

In addition to the production costs of creating the textbooks, there are additional costs involved in getting faculty members to adopt them. For the academic year 2009–2010, FWK experimented with new sales and marketing programs to attract faculty to adopt their textbooks. The financial results of those programs did not appear to be sustainable. The cost to acquire one faculty member under this model was over $2,500, and on average that faculty member’s course delivered about $225 in gross profit. Clearly, those marketing strategies needed further analysis.

For the academic year 2010–2011, Flat World Knowledge made greater use of their internal customer relationship management system, a new lead-generation technique, aggressive and creative public relations, and a Faculty Advocates program. This Faculty Advocates program includes faculty advisors organizing educational workshops on their campuses about the benefits of open textbooks. The results were significantly better. FWK reported that the average cost of faculty acquisition dropped to under $900. And with improvements to the student commerce side of the business, gross profit per adoption climbed above $300. In essence, it takes a faculty member using the textbook for three semesters in order to pay for the costs of acquiring that faculty member. The company hopes for full payback of a faculty acquisition in a single semester by the academic year 2011–2012.

Of the approximately 500 faculty adopters that Flat World Knowledge attracted in the summer and fall of 2009, only 9% were referred to the company via a colleague. Of the almost 1,200 faculty adopters for the summer and fall of 2010, 27% were referred to Flat World Knowledge by a colleague. This may indicate that faculty are having a good first experience with the company’s products and business model and are proactively sharing their experiences with their colleagues. If so, it bodes well for continued efficiency in the cost of acquiring faculty customers and the company’s long-term sustainability.

During the beta period, 59% of students made a purchase through Flat World Knowledge with the average purchase totaling $28.20. Bookstores and other outlets did not sell FWK products during the beta period. During the first year of public operation, 16% of students made purchases directly from FWK with the average purchase totaling $30.89. When bookstore purchases are taken into account, 34% of students purchased a FWK product. Although 39% of students purchased a printed book during the beta period, only 29% purchased a printed book during the first public year. This decrease in the overall percentage of students making a purchase may be problematic for FWK if the trend continues downward as the number of adoptions increases.

For the 2009–2010 school year, the average textbook was responsible for approximately $48,000 in revenue. If the same number of textbooks were sold during each year, it would take approximately three years to recoup the costs of producing these initial books ($150,000, as stated previously). Of course, these numbers do not include administrative, overhead, and other costs not related to the production of books.

We should note, however, that enrollment grew from 790 students in the private beta period to 57,690 students in the first year of normal operation. Should enrollment continue to increase, the amount of time required to recover the costs of book production and to become profitable will decrease.

Many people in higher education have been looking at the possibility of using free and open textbooks (Baker, 2008; Baker, Thierstein, Fletcher, Kaur, & Emmons, 2009). Digital media drives down the marginal cost of additional copies of books, making it possible for many to access the resources at a potentially low cost. Currently, electronic texts represent less than 10% of existing textbook sales (Butler, 2009). Will this figure change soon? Nicholas and Lewis (2009) point out that although “every year is predicted to be the year that electronic textbooks take off,” they haven’t yet done so (p. 4). However, in a small-scale study of middle-class students, they did find that “if an e-textbook were just $25 less than a print version, 75% of the students would select it” (p. 7). They further hypothesized that “at a school with a more diverse student population, such as a community college, cost is likely to be even more of a determining factor” (p. 7). Thus, if textbooks can be given away online for free, e-textbook adoption could really take off.

Although “free” may sound good to consumers, it can be very difficult to make money if you are giving away your product (Anderson, 2009). Michael Jensen of the National Academies Press recently reported that his organization (which makes all of its materials available for free) is facing declining sales (Hadro, 2010). Only a few years earlier, Jensen reported that giving digital books away had increased sales (Jensen, 2007). Thus, when dealing with free digital content, what worked today may not work tomorrow. As FWK moves forward with its specific model, it may encounter challenges if an increasing number of students become comfortable with the free version of its textbooks and choose not to purchase printed books or ancillary materials.

However, if FWK (or other organizations) can find sustainability while distributing free digital textbooks, the textbook market could be dramatically altered. Because it is so hard to compete with “free,” textbook prices would likely come down and eventually become only a small part of the cost of higher education. The potential for the disruption of the textbook publishing industry, as well as the potential savings to students, is enormous if one or more organizations can create a sustainable business model. Whether this can be done remains to be seen.

Albanese, A. (2009, April 21). At London Book Fair, panel says two-year British e- textbook study is myth-shattering. Publishers Weekly. Retrieved from http://www.webcitation.org/5gMCLli4D

Allen, K. (2009, December 28). Amazon e-book sales overtake print for first time. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.webcitation.org/5wCyS7E4r

Anderson, C. (2009). Free: The future of a radical price. New York: Hyperion.

Baker, J. (2008). Culture of shared knowledge: Developing a strategy for low-cost textbook alternatives. New England Journal of Higher Education, 21(1), 30.

Baker, J., Thierstein, J., Fletcher, K., Kaur, M., & Emmons, J. (2009). Open textbook proof-of-concept via Connexions. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(5).

Butler, D. (2009, April 1). Technology: The textbook of the future. Nature, 458, 568–570.

Creative Commons (n.d.). Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/

Downes, S. (2007). Models for sustainable open educational resources. Interdisciplinary Journal of Knowledge & Learning Objects, 3, 29–44. Retrieved from http://ijklo.org/Volume3/IJKLOv3p029-044Downes.pdf

Flat World Knowledge (n.d.). Interview with Preston McAfee. Retrieved from http://www.flatworldknowledge.com/McAfee-Podcast

Foster, A. (2005, August 9). Digital textbook pilot project begins this month in 10 college bookstores. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.webcitation.org/5gMDFKCY5

Gonzalez, J. (2011, January 20). 2-year colleges get details of $2-billion grant program. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/2-Year-Colleges-Get-Details-of/126006/

Hadro, J. (2010, January 21). At SPARC-ACRL forum, reality check on open access monographs. Retrieved from http://www.libraryjournal.com/lj/community/academiclibraries/853514-419/at_sparc-acrl_forum_reality_check.html.csp

Hilton, J., & Wiley, D. (2010). A sustainable future for open textbooks? The Flat World Knowledge story. First Monday, 15(8). Retrieved from http://www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2800/2578

Jensen, M. (2007, Spring). The deep niche. The Journal of Electronic Publishing, 10(2). Retrieved from http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/textidx?c=jep;view=text;rgn=main;idno=3336451.0010.206

Koohang, A., & Harman, K. (2007). Advancing sustainability of open educational resources. Issues in Informing Science & Information Technology, 4, 535–544.

National Association of College Stores. (2009). Higher education retail market facts & figures 2009. Retrieved from http://www.webcitation.org/5gMDN9Htr

Nelson, M. (2011, January 20). E-books in higher education: Nearing the end of the era of hype? Educause Review, 43(2) (March/April 2008). Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/EDUCAUSE+Review/EDUCAUSEReviewMagazineVolume43/EBooksinHigherEducationNearing/162677

Nicholas, A., & Lewis, J. (2009). The net generation and e-textbooks. Salve Regina University Faculty and Staff—Articles & Papers (Paper 17). Retrieved from http://escholar.salve.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=fac_staff_pub

Overland, M. (2011, January 9). State of Washington to offer online materials as texts. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/State-of-Washington-to-Offer/125887/

Wiley, D. (2006). On the sustainability of open educational resource initiatives in higher education. White paper commissioned by OECD. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/33/9/38645447.pdf