Volume 26, Number 2

Richard F. Heller1,* and Stephen R. Leeder2

1University of Newcastle, Australia; 2University of Sydney, Australia; *Corresponding author

This paper documents biases in the creation of knowledge through underrepresentation of diverse populations and population groups in the way research is conducted and published, and subsequently, in the way educational resources are developed and delivered. Research that incorporates the experience of distributed population groups will have greater local applicability, and knowledge published and disseminated in ways that make it available to distributed populations will increase likelihood that the research findings will be incorporated into policy and action across the population. The incorporation of knowledge gained from distributed population groups into the educational experience will enrich it and, like the knowledge, make it more relevant to the whole population. We explore the potential for distributing knowledge creation to contribute in these ways and what changes are required in the way that higher education is organised to maximise distributed knowledge creation, including collaborative co-creation of knowledge and a collaborative capacity-building programme to ensure its sustainability. We propose that the principles described for a distributed university, where education is disseminated largely online through regional hubs to correct local and global inequalities in access, would be suitable to support the development of structures for distributing knowledge creation. Appropriate governance structures should be developed, of which co-creation of knowledge would be an essential component.

Keywords: distributed knowledge creation, knowledge dissemination, co-creation of knowledge, collaboration, open educational resources

While the dissemination of knowledge through distributed and online education is well established in today’s academic scene, distributed knowledge creation is not. Despite this, research that incorporates the experience of distributed population groups will have greater local applicability. Also, knowledge published and disseminated in ways that make it available to distributed populations will increase the likelihood that research findings will be incorporated into policy and action across the population. The incorporation of knowledge gained from distributed population groups into the educational experience will enrich it and, like the knowledge, make it more relevant to the whole population.

The way that knowledge is created through research has evolved in three modes. Mode 1 knowledge creation is the traditional linear style with description or hypothesis-testing within controlled (often laboratory) contexts. Mode 2 knowledge is produced more broadly across disciplines and is set in the context of its application (Gibbons, 2013). Mode 3 knowledge production incorporates both modes 1 and 2, operates in the context of current problems, and is collaborative with both a local and global reach (Carayannis et al., 2016). Mode 3 knowledge creation mirrors the role that many universities have taken, with serious attention to the context and the social and practical applications of the research. We explore the idea of distributing knowledge creation, as a corollary to the dissemination of knowledge through education by distributed means.

Universities play the major role in knowledge creation for society through research, and also in the dissemination of knowledge through education. There is a rich history of distributing education through open and distance learning (ODL), which started before but has been heavily influenced by open universities (Chawinga & Zozie, 2016). Increasing access to education has been the key to the value of ODL, and there are a number of delivery models. Distinct from universities offering some of their courses online, and the open university model where most of the education is delivered online at a distance to individuals from large centralised campuses, a distributed university model has been described (Heller, 2022). This model comprises small, centralised administrative and support functions while education is delivered through local hubs which may be virtual or physical. Distributed learning ecosystems have also been described, which establish “a link between decentralised learning ecosystems (consisting of content repositories and educational resources)... [which]... serve as an integrated approach that enables learners to access and use learning content and share resources” (Otto & Keres, 2023, p. 13).

Research on many topics can be enriched by the perspectives that come with the distribution of talent and representation of voices. Current research studies frequently exclude women, certain geographical areas (especially those in the Global South), and marginalised groups. For example, the lack of female and racial representation in the conducting of clinical trials in medicine diminishes the application of the research findings (Tysinger & Hlávka, 2022). Research in psychology and human behaviour has been criticised for focusing on western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) societies (Henrich et al., 2010). Oxford historian Peter Frankopan, in his wide-ranging The Earth Transformed: An Untold History (2023), wrote:

Study of the past has been dominated by the attention paid to the “global north”... with the history of other regions often relegated to secondary significance or ignored entirely. That same pattern applies to climate science and research into climate history, where there are vast regions, periods and peoples that receive little attention, investment, and investigation.... Much of history has been written by people living in cities, for people living in cities, and has focused on the lives of those who lived in cities. (pp. 77-78)

Hungarian social researcher Márton Demeter wrote:

the accumulation of academic capital is radically uneven with very high concentrations in a few core countries.... the world of science can be separated for a few “winner” or core and many more “loser” or peripheral countries .... loser-country scientists were cited less frequently than winner-country scientists, even in cases where they had been published in the very same journal (Demeter, 2019, p. 121)

The philosophical concept of standpoint epistemology (or standpoint theory of knowledge) is relevant and nicely boiled down by Georgetown University philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò (2021) as: (a) knowledge is socially situated; (b) marginalized people have some positional advantages in gaining some forms of knowledge; and, (c) research programs ought to reflect these facts. Amy Allen (2017), a liberal arts research professor of philosophy and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at The Pennsylvania State University, stated: “Feminist standpoint theory has expanded beyond gender to encompass categories such as race and social class. Recent scholarship calls for studying standpoints of Third World groups in Western societies and marginalized groups in international contexts” (Abstract section, para 1).

Underrepresentation of Indigenous Peoples in research is now widely recognised. An example comes from Arctic Peoples:

Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge systems hold methodologies and assessment processes that provide pathways for knowing and understanding the Arctic, which address all aspects of life, including the spiritual, cultural, and ecological, all in interlinked and supporting ways. For too long, Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic and their knowledges have not been equitably included in many research activities. (Yua et al., 2022, Abstract section, para 1)

The authors proposed a framework for co-production of knowledge—a matter to which we return later in this paper.

During the seminar Decolonizing Knowledge Production. Perspectives From the Global South (Maria Sibylla Merian Center for Advanced Latin American Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences, 2020), representatives of the five Maria Sibylla Merian Centers (India, Mexico, Brazil, Ghana, and Tunisia) discussed the distribution of knowledge production.

The production of knowledge in the global academic field is still highly unevenly distributed. Western knowledge, which originated in Western Europe and was deepened in the transatlantic exchange with North America, is still considered an often unquestioned reference in many academic disciplines. Thus, this specific, regional form of knowledge production has become universalized. (para 1)

In a supplementary issue of the Journal of the British Academy, titled “Repositioning of Africa in Knowledge Production: Shaking off Historical Stigmas,” Crawford et al. (2021) summarised:

Contemporary debates on decolonising knowledge production, inclusive of research on Africa, are crucial and challenge researchers to reflect on the legacies of colonial power relations that continue to permeate the production of knowledge about the continent, its peoples, and societies. (Abstract section, para 1)

A prestigious medical journal, following this theme in The Lancet, said:

Institutions for knowledge production and dissemination, including academic journals, were central to supporting colonialism and its contemporary legacies.... Around the turn of the 20th century, The Lancet helped legitimise the field of tropical medicine, which was designed to facilitate exploitation of colonised places and people by colonisers.... The Lancet must recognise and engage more with different methodologies of knowledge production, beyond the ways of knowing and the types of knowledge that it currently publishes.... The Lancet must divest from the power of its centrality that makes it perpetuate various forms of colonialism. (Khan et al., 2024, pp. 1304-1307)

Abimbola and colleagues (2024), from the universities of Sydney and Utrecht, identified unfair knowledge practices, enacted by those in the centre on behalf of those in the periphery which have affected the ability to achieve global health equity between and within countries.

This bias is due both to lack of research capacity and biases in the publication system. Even when research is undertaken with or on these populations, it may not be accessible to those who might apply the results. The relative lack of scientific publications by authors in the Global South has been widely discussed. Political scientists Medie and Kang (2018) reported that fewer than 3% of articles in four gender and politics journals published in the Global North were written by authors from the Global South. Boyes (2018) had an interesting overview of this issue from a knowledge management perspective, while a geographical perspective on sub-Saharan Africa found that digital content was more evenly geographically distributed than academic articles (Ojanperä et al., 2017).

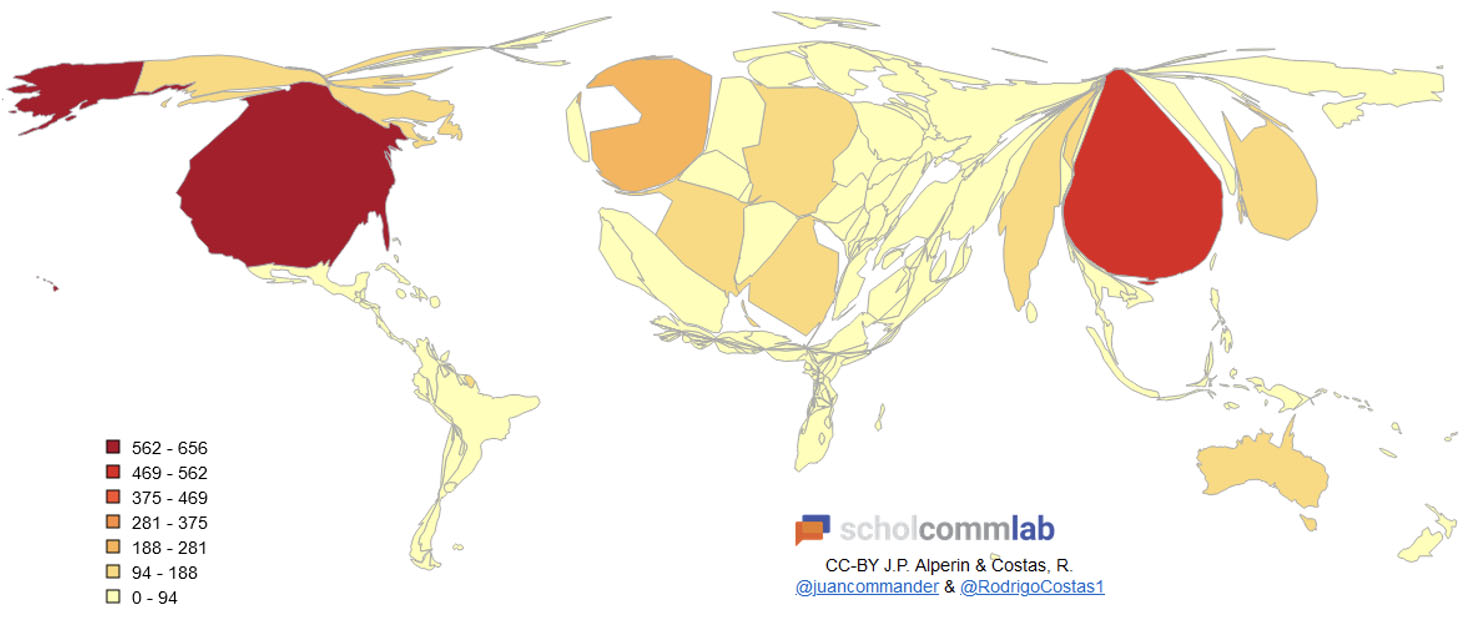

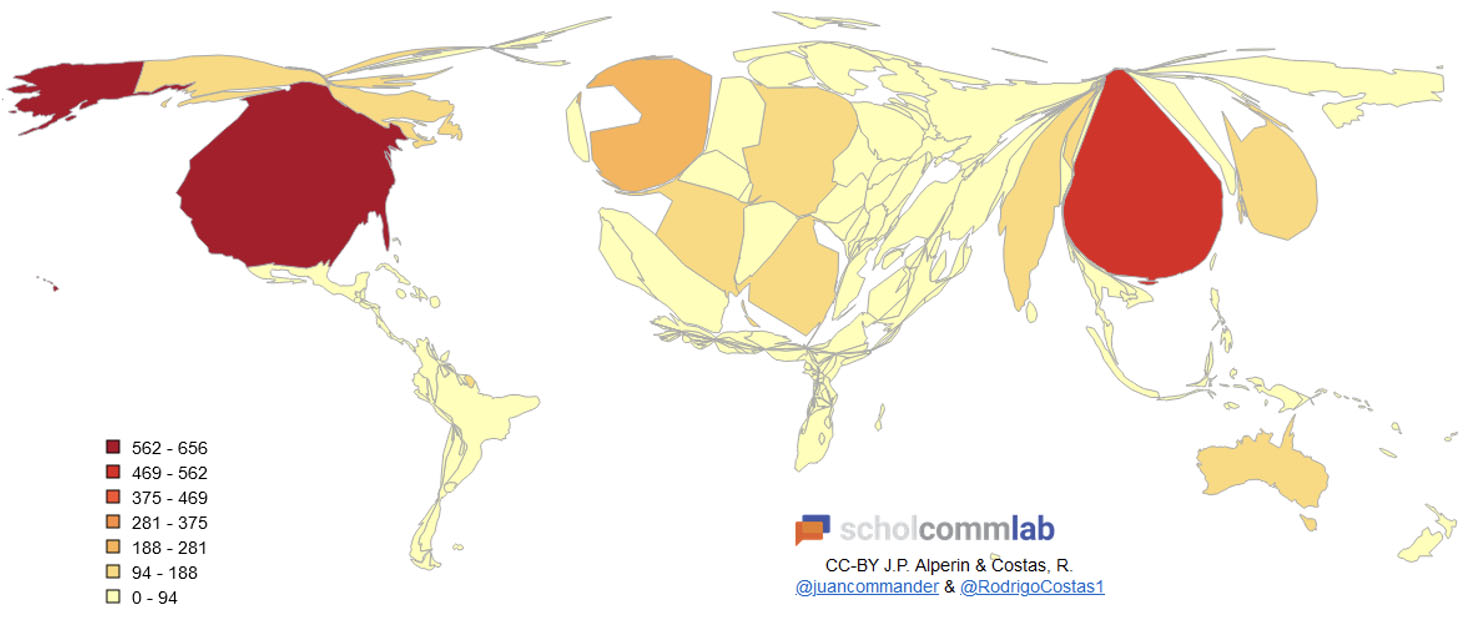

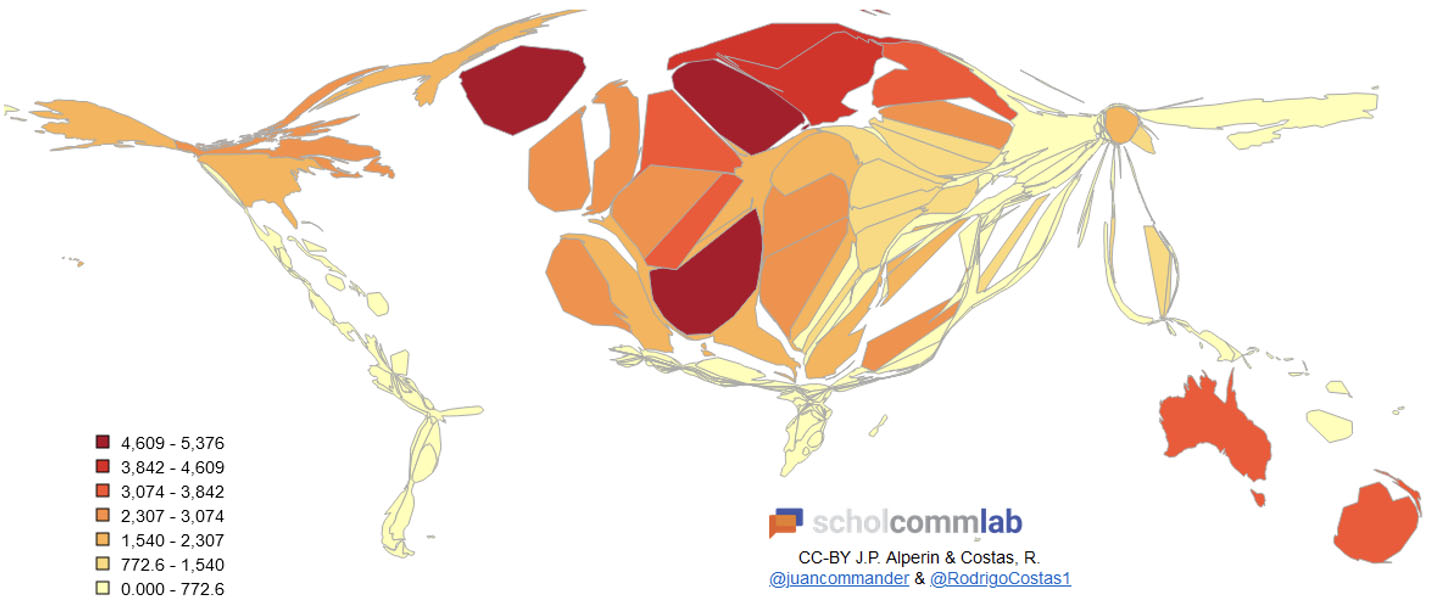

Three world maps scale the apparent size of each country according to the authorship of documents cited on the Web of Science platform (Alperin & Costas, n.d.). When the raw numbers are examined by country, there are gross global differences (Figure 1). These differences are attenuated when the numbers are adjusted for the population size of each country (Figure 2). However, it is not until the figures are adjusted for GDP (Figure 3) that African countries at last become visible on the map.

Figure 1

World Scaled by Number of Documents Cited in the Web of Science in 2017

Note. From World Scaled by Number of Documents Published in 2017 With Authors From Each Country (Publications Counted Once per Country), by J. P. Alperin and R. Costas, n.d., ScholCommLab (https://scholcommlab.ca/cartogram/). CC BY.

Figure 2

World Scaled by Number of Documents Cited in the Web of Science in 2017 as a Proportion of the Population

Note. From World Scaled by Number of Documents Published in 2017 With Authors From Each Country as a Proportion of the Population in 2017, by J. P. Alperin & R. Costas, n.d., ScholCommLab (https://scholcommlab.ca/cartogram/). CC BY.

Figure 3

World Scaled by Number of Documents Cited in the Web of Science in 2017 as a Proportion of Gross Domestic Product

Note. From World Scaled by Number of Documents Published in 2017 With Authors From Each Country as a Proportion of the GDP in 2017, by J. P. Alperin & R. Costas, n.d., ScholCommLab (https://scholcommlab.ca/cartogram/). CC BY.

The patterns may underestimate the geographical disparities as the Web of Science has been criticised for being “structurally biased against research produced in non-Western countries, non-English language research, and research from the arts, humanities, and social sciences” (Tennant, 2020, Abstract section, para 1). Our research on health journals published in 13 African countries found that most journals were not indexed (Agyei et al., 2023). Other valuable research may not appear in journals biased against non-Global North sources. Article processing charges levied on the authors or their institutions are further barriers to publication.

A Global Knowledge Index, developed to guide development programmes, includes areas such as education, ICT, research, development, and economy, and individual country indices (https://www.knowledge4all.com/gki).

If population groups and geographical regions are relatively underrepresented in the research literature, educational examples from these populations are unlikely to find their way into the curriculum. This may be compounded by similar underrepresentation among the academic staff of educational institutions. Postian (2023), an Armenian American writer and a current student at Villanova University in the USA, reviewed the literature and confirmed demographic disparity of authors. She reviewed the courses at Villanova University and found that of the authors represented in undergraduate introductory courses, 70% were men, 90% worked in or originated from the Global North, and 7% were Black academic authors.

Ghai and colleagues (2023), who represent an ethnically diverse group of students and faculty in the Department of Psychology in the University of Cambridge, UK, audited recommended reading materials in the undergraduate curriculum for the psychological and behavioural sciences bachelor’s degree in their institution. They wrote:

All first authors of primary research papers were affiliated with a university in a high-income country—60% were from the United States, with 20% from the United Kingdom, 17% from Europe, and 3% from Oceania. No author was affiliated with an institution based in Africa, Asia, or Latin America.... most of the research studies taught to undergraduates were also based on groups that were predominantly (67%) from the global north. Only 12% of articles included research participants from both the global north and the global south; no study in our reading lists focused on a group solely from the global south. Our syllabus lacked diversity even within the studies: less than 20% of articles reported diversity markers such as income or race, and only 3% mentioned participants’ urban or rural location. (Western bias section, paras 1-2)

Others have reported similar findings. Tamimi et al. (2023) from the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at King’s College London identified a curriculum biased towards white, male scholars and research from the Global North and set this in the context of an exploration of decolonising their curriculum.

Schucan Bird and Pitman (2019) examined reading lists in an undergraduate science module on genetics methodology and a postgraduate social science module on research methods at University College London. The lists were dominated by white, male, and Eurocentric authors, although on the social science reading list, equal proportions of the authors were male and female, and almost a third of authors on the science list identified as Asian. They discussed implications for the growing interest in decolonising curricula across disciplines and institutions. Interest in this area comes from a wide range of disciplines, including the biomedical sciences (Burton & McKinnon, 2013).

Within Africa, attention is being paid to decolonising education. Ifejola Adebisi (2021), a law academic at Bristol University, has provided a thoughtful review:

Essentially, people in Africa have inadequate knowledge of Africa because the inherited colonial systems were not designed to enable them to acquire such knowledge. And people who are outside Africa, who determine what amounts to good knowledge, know even less. Decolonial thought requires us to build global structures that allow all knowledges to equally complete our understanding of the world. (Main Conclusions from the Article section, para 3)

This is echoed in the paper “Gender, Knowledge Production, and Transformative Policy in Africa” where N’Dri Thérèse Assié-Lumumba (2020), a professor and director of the Institute for African Development at Cornell University, argued that:

Contemporary formal African education has been deficient since its inception as it was designed to negate, suppress, and eliminate African culture, promoting inadvertent and deliberate “epistemicide”.... In its philosophy, this received system was also gendered and unequal, with limited access and a less valued curriculum designed for the female population. (Abstract section, para 1)

Zimbabweans Thondhlana and Garwe (2021), in their introduction to the supplementary issue of the Journal of the British Academy titled “Repositioning of Africa in Knowledge Production: Shaking off Historical Stigmas,” concluded that the high quality of the articles “showcases our conviction that Africa can indeed shake off historical stigmas and reposition itself as a giant in knowledge production” (Abstract section, para 1).

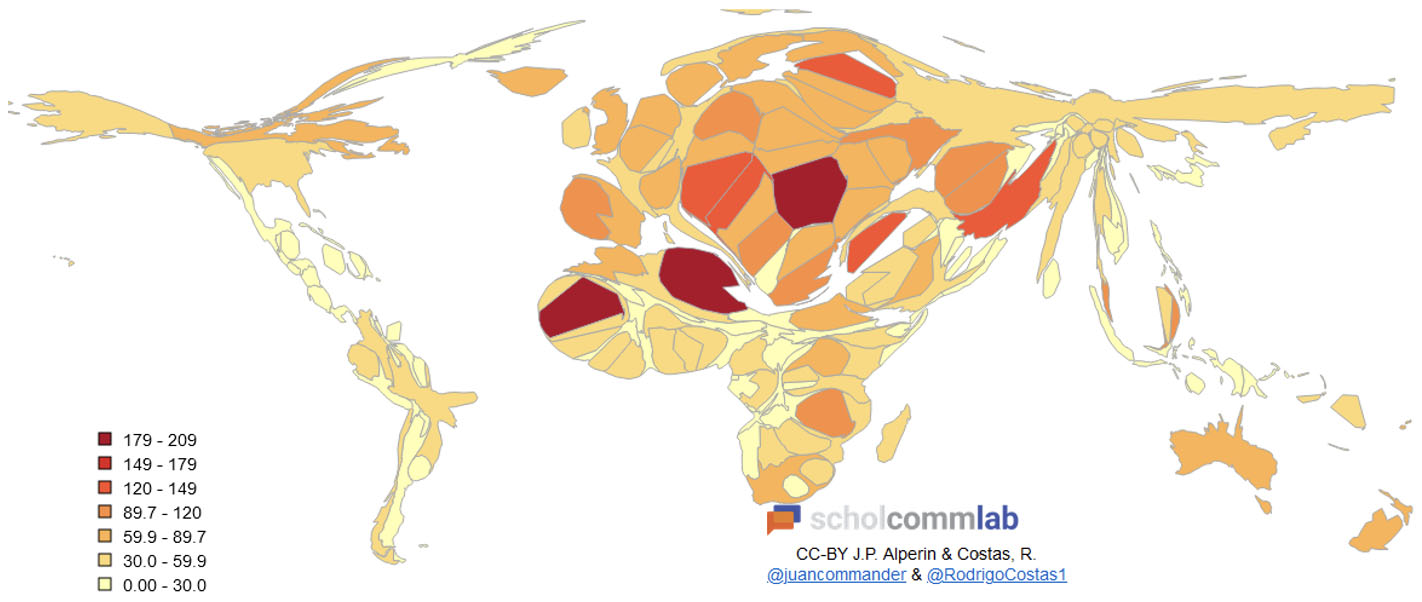

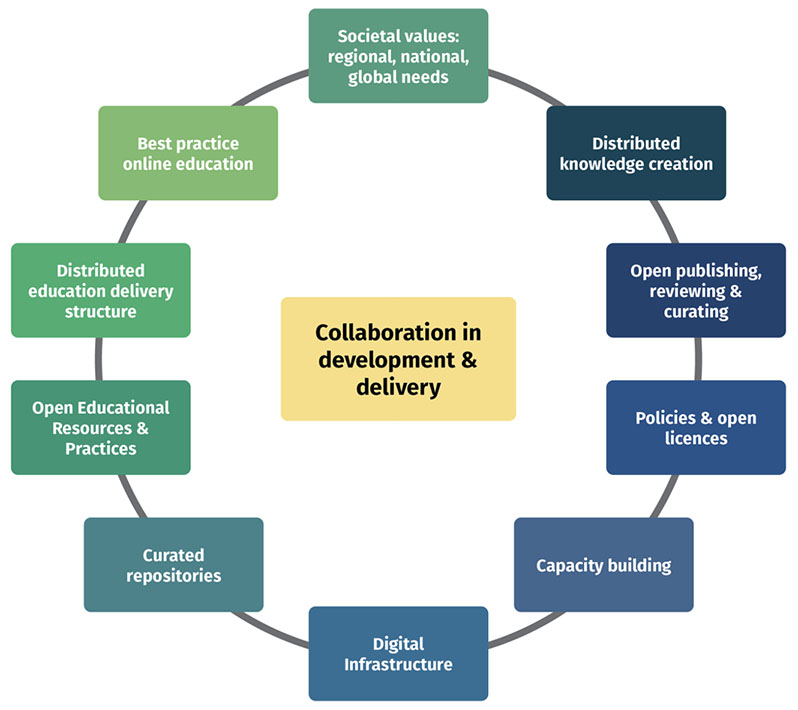

There are many constructs in common between distributing knowledge creation and distributing education, in the broad context of knowledge for equity. The diagram in Figure 4 illustrates a theoretical framework for distributing knowledge for equity into which fits distributed knowledge creation as well as distributed education. This could be considered within the theoretical concept of knowledge equity “a social science concept referring to social change concerning expanding what is valued as knowledge and how communities may have been excluded from this discourse through imbalanced structures of power and privilege” (Knowledge Equity, n.d.). Knowledge equity has been described as one of the foundations of knowledge management (Baskerville & Dulipovici, 2006). Epistemic injustice, as articulated by Bhaumik (2024) is the counterpoint to knowledge equity, and also relevant to our exploration of how the distribution of the creation of knowledge can reduce inequity.

Connectivism is a learning theory for the digital age which “provides insight into learning skills and tasks needed for learners to flourish in a digital era” (Siemens, 2005, Conclusion section, para 2). We have previously described examples of global open online educational programmes as extensions of connectivism (Madhok et al., 2018), and a further extension to include distributed knowledge creation, with its dependence on open digital technologies, would seem appropriate.

Figure 4

Framework for Distributing Knowledge for Equity

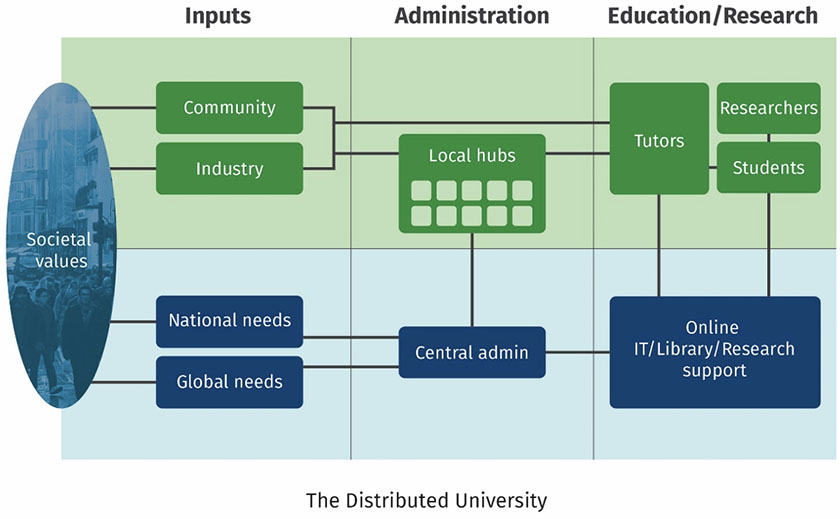

Figure 5 shows the structure of a proposed distributed university which would provide education largely online “where it is needed, reducing local and global inequalities in access, and emphasising local relevance” (Heller, 2022, About this book section, para 1). It could also be relevant to distributing knowledge creation, as well as knowledge dissemination.

Figure 5

The Structure of a Distributed University

Note. From The Distributed University for Sustainable Higher Education (p. 56), by R.F. Heller, 2022, Springer Nature (https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6506-6). CC BY 4.0.

Following the notion of a focus on online education with infrastructure being distributed away from central inner-city campuses towards regional hubs, a similar structure would encourage knowledge creation among the populations to which the education is distributed. The distributed model would encourage co-creation of knowledge—through collaboration with local communities, industries, minority groups, and geographic regions (local, regional, and international).

Researchers and advocates have identified a number of features that would enable the creation of knowledge through distributed means. Some of these are in common with other proposals, which may involve large-scale system change. For example, Laura Czerniewicz (2015), an educational policy innovator from Cape Town, has focused on the north/south publication inequity. She suggested improvements in funding and technology infrastructure, a broadening of concepts of “science,” changing the reward system for publications, and a broadening of the open access movement to participate in knowledge creation. George Richards (2022), from an independent global organisation advancing science, writing for the World Economic Forum, also recommended structural changes, “including access to grants, boosting capital flows, and improving research collaboration” (Summary section, para 3). Dev Nathan (2024), a social scientist from Johannesburg, in a wide-ranging review of knowledge and global inequality, advocated for a new political economy, but suggested some small steps to begin, including attention to intellectual property licencing.

In a policy paper for the OECD, knowledge co-creation was defined as “the process of the joint production of innovation between industry, research and possibly other stakeholders, notably civil society” (Kreiling & Paunov, 2021, p. 6). The paper identified four factors that are essential for successful co-creation: engagement with stakeholders; effective governance and operational management structures; agreement on ownership and intellectual property; and adjustment for changing environments. Although the report focuses on science, technology, and industry, these concepts are applicable to education. Melanie Zurba (2021) from Dalhousie University makes the point with her colleagues that contextual diversity needs to feature with the context of Indigenous knowledge co-creation—a field where there is much activity (Maclean et al., 2022; Yua et al., 2022). Carina Wyborn, an interdisciplinary social scientist at the Australian National University, and international colleagues from the sustainability sciences, insisted co-creation processes should lead to societal outcomes (2019).

There is a substantial literature about students learning together and co-creating knowledge (Bovill, 2020), and a whole journal is devoted to “students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education” ( International Journal for Students as Partners, https://mulpress.mcmaster.ca/ijsap/about). Lay involvement in co-production of knowledge also has potential, including citizen science projects (Curtis, 2018; Palumbo et al., 2021).

We assert that, in the pursuit of greater equity, knowledge creation should be distributed among populations and groups currently underrepresented. However, that does not lead automatically to greater publication of that knowledge. A desirable goal would be that publication of the knowledge produced should be accessible both to the scientific community and potential users. The lines shown in Figure 5 do not have arrows: the flow of knowledge should be two-way, with feedback coming from the community and industry to the knowledge creators, and vice versa. The role of open publishing of research, including preprints and open reviews, has potential to make a contribution (Corker et al., 2024; Ruredzo et al., 2024; Smith et al., 2017). As for research, open access to educational materials is relevant. Open educational resources (OER) and practices are offered by many providers. Proposals have been made for a distributed learning ecosystem for OER (Otto & Kerres, 2023) and for free public access to a broader range of educational materials (Heller, 2023).

There is much activity among universities in decolonising their curricula (Shahjahan et al., 2021). We propose that distributing knowledge creation is a necessary step in this process. However, as for publication, structures will be needed that encourage the incorporation of knowledge generation into these programmes. Open access to educational resource repositories will be important, as will other drivers, as discussed by US educationalists Shahjahan and colleagues, that may flow from increasing the diversity of academic staff. Community open online courses have been developed that demonstrate the benefits of widening the range of who is involved in producing educational programmes (Shukie, 2019).

As was shown in Figure 5, the distributed university model envisages direct collaboration between both industry and community with teachers and researchers who are mainly based in regional hubs—which can be physical or virtual. As with education, research activities can be performed collaboratively online but others require physical co-location. Wet lab research will need to be carried out in physical hubs, and these may be co-located with industry partners. A taxonomy of the type of research best suited to a distributed mode would clarify a range of possibilities.

Managing the organisation of research among distributed teams can be tackled in several ways. The transdisciplinary scientist from Catalonia, Hidalgo (2019), has described the importance of teamwork and the benefits of agile project management. Management through distributed leadership has been proposed as an alternative to bureaucracy by Lumby (2019), an educationalist from Southampton University. Many distributed research networks are well established, for example, multicentre clinical trials (Marsolo et al., 2020), supported with innovative software (Davies et al., 2016). Many of the same imperatives would apply to distributed education.

There is a need to build capacity among academics and collaborative partners for distributing knowledge creation. This could be in tandem with increasing capacity for distributing knowledge dissemination, as some of the structures and participants may be the same. One approach might be the collaborative development of a course which, in the process, could help refine the necessary structures and lead to a cadre of advocates. The online course Distributing learning and knowledge creation (Peoples-Praxis, n.d.) is such an example.

We have focused on the underrepresentation of diverse populations and population groups in research studies, research publications, and educational programmes. We propose that the principles described for a distributed university, where education is disseminated largely online through regional hubs to correct local and global inequalities in access, would be suitable to support the development of structures for distributing knowledge creation. Appropriate governance structures should be developed, of which co-creation of knowledge would be an essential component.

This approach should be seen in the context of an overall framework for the equitable distribution of knowledge, of which open education and publishing, as well as distributed knowledge creation, are key components.

Abimbola, S., van de Kamp, J., Lariat, J., Rathod, L., Kerstin-Grobusch, K., van der Graaf, R., & Bhakuni, H. (2024). Unfair knowledge practices in global health: A realist synthesis. Health Policy and Planning, 39(6), 636-650. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czae030

Adebisi, F. I. (2021, February 1). Decolonising education in Africa—Five years on. African Skies. https://folukeafrica.com/decolonising-education-in-africa-five-years-on/

Agyei, D.D., Sangare, M., Anyiam, F.E., Ruredzo, P.I.M., Warnasekara, J., & Heller, R.F. (2023) Open access publication of public health research in African journals. Insights: the UKSG Journal, 36(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.605

Allen, B. J. (2017). Standpoint theory. In Y. Y. Kim (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of intercultural communication (pp. 1-9). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783665.ieicc0234

Alperin, J. P., & Costas, R. (n.d.). World scaled by number of documents published in 2017 with authors from each country as a proportion of the GDP in 2017. ScholCommLab. Retrieved May 21, 2024, from https://scholcommlab.ca/cartogram/

Alperin, J. P., & Costas, R. (n.d.). World scaled by number of documents published in 2017 with authors from each country as a proportion of the population in 2017. ScholCommLab. Retrieved May 21, 2024, from https://scholcommlab.ca/cartogram/

Alperin, J. P., & Costas, R. (n.d.). World scaled by number of documents published in 2017 with authors from each country (publications counted once per country). ScholCommLab. Retrieved May 21, 2024, from https://scholcommlab.ca/cartogram/

Assié-Lumumba, N’D. T. (2020). Gender, knowledge production, and transformative policy in Africa: Background paper for the Futures of Education initiative. UNESCO, Education Sector. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374154

Baskerville, R., & Dulipovici, A. (2006). The theoretical foundations of knowledge management. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 4(2), 83-105. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.kmrp.8500090

Bhaumik, S. (2024). On the nature and structure of epistemic injustice in the neglected tropical disease knowledge ecosystem. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 18(12), e0012781. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0012781

Bovill, C. (2020). Co-creation in learning and teaching: The case for a whole-class approach in higher education. Higher Education, 79(6), 1023-1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w

Boyes, B. (2018, August 9). How do we fix the world’s very unequal knowledge—and knowledge management—map? RealKM Magazine. https://realkm.com/2018/08/09/how-do-we-fix-the-worlds-very-unequal-knowledge-and-knowledge-management-map/

Burton, B., & McKinnon, C. (2022, March 17). Decolonising the immunology curriculum: Starting to interrogate structural inequalities in science. British Society for Immunology. https://www.immunology.org/news/decolonising-immunology-curriculum-starting-interrogate-structural-inequalities-science

Carayannis, E. G., Campbell, D. F. J., & Rehman, S. S. (2016). Mode 3 knowledge production: Systems and systems theory, clusters and networks. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 5(1), Article 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-016-0045-9

Chawinga, W. D., & Zozie, P. A. (2016). Increasing access to higher education through open and distance learning: Empirical findings from Mzuzu University, Malawi. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(4), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i4.2409

Corker, K. S., Waltman, L., & Coates, J. A. (2024, October 10). Understanding the Publish-Review-Curate (PRC) model of scholarly communication. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/h7swt

Crawford, G., Mai-Bornu, Z., & Landström, K. (2021). Decolonising knowledge production on Africa: Why it’s still necessary and what can be done. Journal of the British Academy, 9(s1), 21-46. https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/009s1.021

Curtis, V. (2018). Online citizen science and the widening of academia: Distributed engagement with research and knowledge production. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77664-4

Czerniewicz, L. (2015, July 8). It’s time to redraw the world’s very unequal knowledge map. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/its-time-to-redraw-the-worlds-very-unequal-knowledge-map-44206

Davies, M., Erickson, K., Wyner, Z., Malenfant, J., Rosen, R., & Brown, J. (2016). Software-enabled distributed network governance: The PopMedNet experience. EGEMS (Washington, DC), 4(2), 1213. https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1213

Demeter, M. (2019). The world-systemic dynamics of knowledge production: The distribution of transnational academic capital in the social sciences. Journal of World-Systems Research, 25(1), 111-144. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2019.887

Frankopan, P. (2023). The earth transformed: An untold history. Bloomsbury.

Ghai, S., de-Wit, L., & Mak, Y. (2023, March 1). How we investigated the diversity of our undergraduate curriculum. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00614-z

Gibbons, M. (2013). Mode 1, mode 2, and innovation. In E. G. Carayannis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of creativity, invention, innovation and entrepreneurship (pp. 1285-1292). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3858-8_451

Heller, R. F. (2022). The distributed university for sustainable higher education. In SpringerBriefs in Education. Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6506-6

Heller, R. F. (2023). Plan E for education: Open access to educational materials created in publicly funded universities. Insights: The UKSG Journal, 36(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.607

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x0999152x

Hidalgo, E. S. (2019). Adapting the scrum framework for agile project management in science: Case study of a distributed research initiative. Heliyon, 5(3), Article e01447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01447

Khan, M. S., Naidu, T., Torres, I., Noor, M. N., Bump, J. B., & Abimbola, S. (2024). The Lancet and colonialism: Past, present, and future. The Lancet, 403(10433), 1304-1308. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00102-8

Knowledge Equity. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved January 8, 2025, from https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knowledge_equity

Kreiling, L., & Paunov, C. (2021). Knowledge co-creation in the 21st century: A cross-country experience based policy report. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/innovation/knowledge-co-creation-in-the-21st-century-c067606f-en.htm

Lumby, J. (2019). Distributed leadership and bureaucracy. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 47(1), 5-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217711190

Maclean, K., Greenaway, A., & Grünbühel, C. (2022). Developing methods of knowledge co-production across varying contexts to shape Sustainability Science theory and practice. Sustainability Science, 17(2), 325-332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01103-4

Madhok, R., Frank, E., & Heller, R.F. (2018) Building public health capacity through online global learning, Open Praxis, 10(1), 91-97. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.1.746.

Maria Sibylla Merian Center for Advanced Latin American Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences. (2020). Decolonizing knowledge production. Perspectives from the Global South. http://calas.lat/en/eventos/decolonizing-knowledge-production-perspectives-global-south

Marsolo, K. A., Brown, J. S., Hernandez, A. F., Hammill, B. G., Raman, S. R., Syat, B., Platt, R., & Curtis, L. H. (2020). Considerations for using distributed research networks to conduct aspects of randomized trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 17, Article 100515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100515

Medie, P. A., & Kang, A. J. (2018, July 29). Global South scholars are missing from European and US journals. What can be done about it. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/global-south-scholars-are-missing-from-european-and-us-journals-what-can-be-done-about-it-99570

Nathan, D. (2024). Knowledge and global inequality since 1800: Interrogating the present as history. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009455183

Ojanperä, S., Graham, M., Straumann, R. K., De Sabbata, S., & Zook, M. (2017). Engagement in the knowledge economy: Regional patterns of content creation with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Information Technologies & International Development, 13, 33-51. https://itidjournal.org/index.php/itid/article/view/1479.html

Otto, D., & Kerres, M. (2023). Distributed learning ecosystems in education: A guide to the debate. In D. Otto, G. Scharnberg, M. Kerres, & O. Zawacki-Richter (Eds) Distributed learning ecosystems (pp. 13-30), Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-38703-7_2

Palumbo, R., Manna, R., & Douglas, A. (2021). Toward a socially-distributed mode of knowledge production: Framing the contribution of lay people to scientific research. International Journal of Transitions and Innovation Systems, 6(4), 381-402. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtis.2021.116851

Peoples-Praxis. (n.d.). Distributing learning and knowledge creation. https://courses.peoples-praxis.org/course/view.php?id=30

Postian, T. (2023). Who is represented? An evaluation of demographic disparity across Villanova University’s syllabi. Veritas: Villanova Research Journal, 1, 56-66. https://veritas.journals.villanova.edu/index.php/veritas/article/view/2892/2752

Ruredzo, P. I. M., Agyei, D. D., Sangare, M., & Heller, R. F. (2024). Open publishing of public health research in Africa: an exploratory investigation of the barriers and solutions. Insights: The UKSG Journal, 37(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.635

Richards, G. (2022, February 4). Three ways to address the North-South divide in scientific research. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/02/north-south-divide-scientific-research/

Schucan Bird, K., & Pitman, L. (2019). How diverse is your reading list? Exploring issues of representation and decolonisation in the UK. Higher Education, 79(5), 903-920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00446-9

Shahjahan, R. A., Estera, A. L., Surla, K. L., & Edwards, K. T. (2021). “Decolonizing” curriculum and pedagogy: A comparative review across disciplines and global higher education contexts. Review of Educational Research, 92(1), 73-113. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211042423

Shukie, P. (2019). Teaching on Mars: Some lessons learned from an earth-bound study into community open online courses (COOCs) as a future education model rooted in social justice. Sustainability, 11(24), Article 6893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246893

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1). http://itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm

Smith, E., Haustein, S., Mongeon, P., Shu, F., Ridde, V., & Larivière, V. (2017). Knowledge sharing in global health research—The impact, uptake and cost of open access to scholarly literature. Health Research Policy and Systems, 15, Article 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0235-3

Táíwò, O. (2021). Being-in-the-room privilege: Elite capture and epistemic deference. The Philosopher, 108(4). https://www.thephilosopher1923.org/post/being-in-the-room-privilege-elite-capture-and-epistemic-deference

Tamimi, N., Khalawi, H., Jallow, M. A., Torres Valencia, O. G., & Jumbo, E. (2023). Towards decolonising higher education: A case study from a UK university. Higher Education, 88, 815-837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01144-3

Tennant, J. (2020). Web of Science and Scopus are not global databases of knowledge. European Science Editing, 46, Article e51987. https://doi.org/10.3897/ese.2020.e51987

Thondhlana, J., & Garwe, C. (2021). Repositioning of Africa in knowledge production: Shaking off historical stigmas—Introduction. Journal of the British Academy, 9(s1), 1-17.

Tysinger, B., & Hlávka, J. P. (2022, May 17). Why diverse representation in clinical research matters and the current state of representation within the clinical research ecosystem. In K. Bibbins-Domingo, & A. Helman (Eds.), Improving representation in clinical trials and research: Building research equity for women and underrepresented groups (pp. 23-46). National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK584396/

Wyborn, C., Datta, A., Montana, J., Ryan, M., Leith, P., Chaffin, B., Miller, C., & van Kerkhoff, L. (2019). Co-producing sustainability: Reordering the governance of science, policy, and practice. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 44(1), 319-346. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-101718-033103

Yua, E., Raymond-Yakoubian, J., Daniel, R. A., & Behe, C. (2022). A framework for co-production of knowledge in the context of Arctic research. Ecology and Society, 27(1), Article 34. https://doi.org/10.5751/es-12960-270134

Zurba, M., Petriello, M. A., Madge, C., McCarney, P., Bishop, B., McBeth, S., Denniston, M., Bodwitch, H., & Bailey, M. (2021). Learning from knowledge co-production research and practice in the twenty-first century: Global lessons and what they mean for collaborative research in Nunatsiavut. Sustainability Science, 17(2), 449-467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00996-x

Distributing Knowledge Creation to Include Underrepresented Populations by Richard F. Heller and Stephen R. Leeder is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.