Kavita Rao

University of Hawaii, USA

Charles Giuli

Pacific Resources for Education and Learning, USA

Keywords: Distance Learning; Pacific Islands; indigenous education

Access to higher education in the U.S-affiliated Pacific Islands is limited. The island nations and territories in this Pacific region are geographically dispersed and separated by thousands of miles of ocean. Although local and regional colleges offer undergraduate degrees (associate’s and bachelor’s levels), islanders who seek graduate-level education have to move away from home or avail themselves of distance education opportunities in order to earn degrees at the master’s and doctoral levels.

To address a need for building the capacity of educational leaders in the Pacific to conduct and utilize program evaluation appropriately and effectively, Pacific Resources for Education and Learning (PREL) and the University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM) partnered to deliver a two-year, online master’s degree program. With funds provided by a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), PREL and UH developed the Regional Education Master’s Online Training in Evaluation (REMOTE) program to provide this educational opportunity to students located on several islands in the geographically vast and diverse Pacific region.

In this paper, we present the results from an evaluation of the two-year program. The program evaluation was conducted to understand the issues that an online student in the Pacific region faces. These Pacific island students are from indigenous communities and live in rural settings. Many speak English as a foreign language. As adult learners who are mid-career working professionals, they undertake an online program with many concurrent commitments to family, work, and community.

Nineteen students were selected for the REMOTE program through a process that involved island chiefs of education and the University of Hawaii. Students were nominated by State Educational Agency chiefs and Institute of Higher Education presidents from islands across the U.S.-affiliated Pacific, including American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), the Federated States of Micronesia (Chuuk, Kosrae, Pohnpei), Guam, Hawaii, the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), and the Republic of Palau. The nominees applied to the University of Hawaii Graduate Division and had to meet admission requirements.

After all selection criteria were met, the original cohort consisted of three students from America Samoa, two students from the islands of RMI, Kosrae, Chuuk, and CNMI, and one student from the islands of Pohnpei, Palau, Guam, and Hawaii. These 15 students were joined by four more whose tuition was paid by the American Samoa Department of Education. This original cohort of 19 students represented a group scattered across thousands of miles of ocean and located on nine different islands.

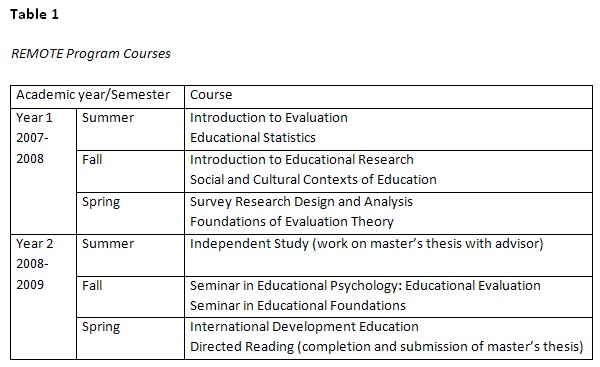

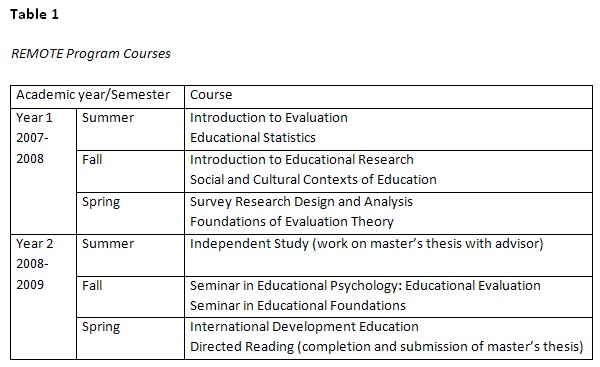

The curriculum was administered by the Department of Educational Foundations of the UHM’s College of Education. The department created a special track, within its existing Master’s in Education program, specifically for the Pacific cohort. The REMOTE cohort had to complete 10 courses (see Table 1) during the two-year program and submit a master’s thesis in order to graduate.

All courses were taught online, using WebCT and Sakai course management systems. The only exception was a face-to-face meeting for part of the first summer semester, funded by the grant. Students convened in Honolulu in person for two weeks at the start of the program as an orientation and kickoff. They met some of the REMOTE instructors and received training on the online technologies they would be using during the two years of study. Instructors of the two summer courses also delivered part of their courses during this two-week orientation. Students completed those two courses online after returning to their islands. The remaining eight courses were conducted entirely online, with no additional face-to-face meetings.

Courses were offered largely in an asynchronous format, with course management software and email as the primary means of communication. When students first returned to their islands, program staff implemented ways to bring the cohort together using synchronous technologies. The staff began using teleconferencing and web-conferencing as a way to bring students together to discuss questions and issues. Course instructors also began to use web-conferencing (using Elluminate Live! software) to convene students in their courses periodically. These synchronous meetings were optional and informal, not a required element of the program.

During the two years of the program, students’ primary interactions were with course instructors and the REMOTE program director. The instructors were all professors or adjunct professors at the UHM Educational Foundations department, and the program director was an educational technology specialist at PREL. The program director managed the project and played a significant role in organizing operations and interfacing with students regarding operational matters. Students were also assigned individual advisors to help them with their master’s thesis papers.

To guide the design of this program evaluation and our development of questions for the surveys and interviews, we narrowed our examination of the extensive body of literature on online learning to studies conducted with students who have similar cultural and geographical profiles to the participants of the REMOTE program. The following section provides an overview of findings from prior studies conducted with indigenous learners, some of whom lived in similar rural and underresourced settings as did the Pacific Islanders in the REMOTE cohort. This section also provides background on evaluation methods for online learning that informed our formative and summative evaluation of the REMOTE program.

Researchers note that online learners from indigenous communities face unique challenges (Berkshire & Smith, 2000; McLoughlin, 1999; Zepke & Leach, 2002). These researchers suggest that to give students a chance to succeed in online programs and courses, instructional design should consider the cultural modes and preferences of the students being served. Berkshire and Smith discussed the unique cultural circumstances of the native Alaskan student, basing their study on the Rural Alaska Native Adult (RANA) program at the Alaska Pacific University. They noted that family duties and obligations are central to the lives of many native Alaskans and highlighted the importance of accommodating these cultural components in the courses offered.

Based on her work with adult indigenous learners in Australia, McLoughlin (1999) discussed the need to incorporate the skills and values of the community in order to create authentic learning contexts. She recommended designing instruction that takes into account cultural traditions, issues, and problems. She highlighted the necessity of asking learners about their preferences before designing a course, rather than assuming that the characteristics of one group will fit others. Zepke and Leach (2002) described the importance of community and collaboration in their studies of online learners from Maori communities in New Zealand.

Researchers also note that Pacific Islanders involved in distance learning experiences value face-to-face meetings and synchronous opportunities for communication and interactions (Ho & Burniske, 2005; Rao, 2007). Ho and Burniske studied the use of videoconferencing in courses developed for students in American Samoa. Rao studied the use of web-conferencing in courses developed for students in Micronesia. In both cases, students found that these synchronous technologies helped mitigate feelings of isolation and helped create a sense of community and a relationship with instructors, which they missed in asynchronous forms of distance learning.

Toth, Foulger, and Amrein-Beardsley (2008) emphasized the importance of embedding continuous evaluation measures into hybrid degree programs in order to improve instruction and student learning within the program. They noted the importance of implementing lessons learned from formative evaluation to increase satisfaction, learning, and success for participants.

Research designs that utilize quantitative and qualitative data can be a useful way to assess online courses (Lebec & Luft, 2007). These mixed methods studies can provide descriptive and statistical data as well as additional contextual information on teaching and learning processes that aid the interpretation of results.

For example, Lebec and Luft (2007) noted that quantitative studies of DL suggest that there is no essential difference between courses taught via distance and those taught face-to-face. They stated that these results often assess superficial learning outcomes, but do not evaluate the meaningful learning and deeper levels of understanding of content. By merging quantitative and qualitative data in their study of an online biology course, they were able to analyze more finely what factors worked for students in this distance learning format. The mixed method format allowed researchers to examine student attitudes that hindered the learning experience and resulted in a lack of engagement, such as a lack of intrinsic motivation and frustrations with some facets of the course.

The purpose of this study was to identify promising practices and common challenges faced by students enrolled in a multiyear, online degree program. We also sought to determine (a) the unique challenges experienced by students from rural areas and traditional cultures and (b) what factors helped them to stay on track and graduate on time. The students in this program were all mid-career working professionals who lived in rural settings and who were from traditional cultures and indigenous communities.

Evaluations of online programs often focus on student experiences in a single course; this study examined the processes that took place during the two-year program in order to understand the issues faced by Pacific Islanders as they undertake a rigorous online course of study. From this study of students’ perspectives on their experience as online learners in a graduate degree program, we developed recommendations for designers of online programs for students in similar settings and situations.

Our approach to the evaluation activities and design was governed by our purpose of understanding and improving the delivery of online learning through the experiences participants had completing the course. The majority of evaluation activities conducted for this study were formative rather than summative (Scriven, 1967; 1991). The primary purpose of this program evaluation effort was to include ongoing and continuous improvement of program components during program implementation. A secondary purpose was to obtain information that would allow us to reach summative conclusions of the students’ perceptions of the program overall. Surveys administered throughout the duration of the program helped us understand the significance of student experiences for continuous course improvement. The information obtained from these surveys, often called quantitative data, added a critical perspective to our evidence. The information obtained from the interviews, often called qualitative data, was important for informing our understanding of the program in ways not available from quantitative information (Green, 1997; Maxwell, 2004; Lincoln, 2002; Patton, 2002).

To examine the factors of an online graduate degree program that affect the students’ experiences in the program, the following research questions were developed:

We collected data using end-of-course surveys and end-of-program interviews with students, instructors, and program administrators. The end-of-course surveys contained fixed-response questions with five-point Likert scales and open-ended questions.

Data were collected from students, instructors, advisors, and program administrators. Of the original cohort of 19 students, 8 completed the required coursework and graduated in the two-year time span of the course; 7 students dropped out; and 4 students were close to completion with no more than two courses and the master’s thesis not completed. These four students stated their intention to complete the program by finishing their coursework in two additional semesters. Five course instructors, six advisors, and three program administrators participated in the majority of the two-year program. All were based in Honolulu, Hawaii and were affiliated with either PREL or UHM.

Students completed the end-of-course surveys (Appendix A) using an online survey tool. Responses were anonymous. At the end of the two-year program, an evaluator contacted all 19 students who were originally enrolled in the program. Students were asked whether they could be contacted by phone and were given the choice of answering questions via email. Six students who were enrolled for the full two years participated in interviews by phone and two students who had dropped out of the program responded to the questions by email. The interview protocol can be found in Appendix B.

Three of the five instructors who taught REMOTE courses responded to the instructor interview questionnaire (Appendix C). All five program administrators who were queried responded to the administrator interview questionnaire (Appendix D) via email.

Results are presented in the following subsections: (a) end-of-course survey, closed-ended responses; (b) student comments, which include responses from the open-ended survey items and interviews; c) instructor comments; and d) administrator comments.

At the completion of each REMOTE course, students completed a 22-item end-of-course questionnaire like those typically used to evaluate course satisfaction (Appendix A). Seventeen items were closed-ended and used five response categories (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree). These fixed-choice items were divided in two sections with roughly the same number of items. The first section assessed the pedagogical practices of the instructors (such as clarity of expectations, provision of feedback, and use of culturally relevant perspectives – items 2, 3, and 7, respectively). The second section of the questionnaire assessed the instructional climate generally (whether different learning styles were accommodated, whether the distance learning format was successful, and whether students felt isolated – items 9, 12, and 16, respectively).

The percentage of responses given for the agree responses (agree and strongly agree aggregated) were interpreted to indicate a satisfactory outcome. The average percentage of responses across all questionnaires that were either agree or strongly agree was 82. That is, on average, 82% of respondents felt favorably about the instructional practices of the REMOTE instructors as well as the general instructional climate. Because the overall feelings of participants about the courses were quite positive, and because there was little variation on these responses, the fixed-choice results for the end-of-course questionnaires were not analyzed further.

In this section, we report key themes that emerged from the end-of-course survey, open-ended questions, and the interview data gathered at the end of the program. Students reported challenges to their progress, factors that helped them succeed in the program, ways to improve the course, and the relevance of the course to their work.

Finding time to do coursework was the most common challenge stated. As professionals who had jobs and obligations to family and community, most students reported difficulty keeping up with deadlines and completing coursework. Issues with technology were the second most prevalent challenge. Students cited various problems, for instance slow Internet connections and a lack of knowledge about basic computing skills. The University changed course management software in the middle of the program, and this change created challenges for many students who had gotten used to the interface of the older course management system. Students also said that assignments in some courses were overwhelming at times, with too much reading to do or textbooks that were too complicated to understand.

The factors that helped students succeed included personal interactions during the course, organization and clarity of the course, and appreciation for course content. In the end-of-course surveys, students noted that they valued opportunities to interact with one another as part of their course activities. The discussion forum in the online course was useful and engaging. Students also stated that they appreciated it when courses were well laid out (in the course management software), instructors stated expectations clearly, and the course was well organized. Students emphasized that they appreciated course content that had relevance to their local scenarios. They found the resources used in courses, such as textbooks and articles, useful and thought provoking.

When students were interviewed at the end of the two year program and reflected on the program as a whole, they felt that the factors that helped them succeed were support from the program staff (instructors, program director, and advisors), the face-to-face group meeting at the start of the program, and the fact that course content was locally relevant. Many students said they liked having web-conference meetings during the courses, during which they could interact with instructors and other students synchronously. Students appreciated the communication they had with advisors, instructors, and program staff and cited the extra time put in by all staff to reach out and keep the students engaged as key factors in their ability to complete the program. The instructors’ flexibility and personal touches were often cited as factors that made students persevere when it became difficult to juggle coursework and other life responsibilities.

Asked what changes they would make to the program, student suggestions included a mandatory weekly meeting by phone or web-conferencing, having local coordinators on their home islands for the program, and more opportunities for face-to-face meetings.

In addressing interview questions about the efficacy of the two-year program, students stated that they were able to use what they learned in their jobs. They learned the importance of using assessment in their various positions, and they used their new skills in their work settings. Reflecting on what they thought about the distance learning format, they said that although learning online was challenging, it was a great opportunity to earn a degree without having to leave behind families and jobs.

Instructors commented that factors in student success included face-to-face sessions, web-conferencing, and discussion boards within courses. They noted that a student’s individual drive played a large part in his or her success.

They felt that the greatest challenges for students included English language proficiency, finding time to do coursework, and problems with technical infrastructure. Because of these, instructors said that students often had trouble meeting course deadlines. To address these challenges, instructors said that in future courses they would find more accessible texts for speakers of English as a foreign language, reduce the number of assignments, and be more realistic about how much content they could teach in one semester.

In reflecting on their own challenges as online instructors for this group, they noted that it took longer to establish rapport with students in the online format than it would in a face-to-face format. They also noted that it was far more time consuming to teach online; at times, they felt as though they were conducting multiple individual tutorials. One instructor noted that she was astonished at how much time students were putting into coursework each week.

Instructors commented that in order to have coherence and consistency in a program like this, only a few faculty members should teach all courses. One instructor noted that a two-year program like this may be too long for students who have many other responsibilities and that a series of single-year certificate programs may be a better option.

The administrators noted that the factors in the success of the program included the face-to-face session during the first summer, the oversight by the program director, and the fact that the program was successfully implemented on a limited budget. They noted that the hard work and flexibility of the instructors were key to the success of the program. They were also impressed by the goodwill and attitude of the students.

The challenges noted by administrators included the competition for time that students faced in balancing work and life commitments with program demands. They also noted that the computer and Internet infrastructure created hurdles for students to learn online and that writing an academically rigorous final thesis was challenging for those who used English as a foreign language. One administrator noted that the program may have been too short and suggested adding another semester to give students extra time and flexibility to complete all requirements. Another administrator noted that it was challenging for students to work on inquiry-based projects for their final thesis in this distance format.

Administrators stated that the challenges for the program as a whole included the relatively small budget for this program, the issues created by the cultural barriers and maintaining the integrity of a master’s degree program, the failure to provide sustained mentoring for students, and the lack of applicants who were better qualified for graduate work.

The administrators agreed that more synchronous meetings should be built into the program via face-to-face sessions or a more systematic use of web-conferencing software. Administrators also emphasized the need to build in more structures to support students, such as program advisors who could travel to their sites and advisors who were paid staff (in the case of REMOTE, advisors volunteered their time to the project).

Eight students (42%) of the original 19 REMOTE cohort graduated on time. Four students (21%) came close to completion. Although this graduation rate (42%) is not low for online programs, it is worth considering what supports and strategies online degree programs need in order to keep students motivated and on track for course completion and graduation. In rural and isolated settings, such as the Pacific island nations served by the REMOTE program, it is also important to keep in mind the cultural and environmental factors that affect a student’s participation in an online degree program.

We discuss the major findings and propose some considerations for future program and course designers working with similar populations or in similar settings. End-of-course surveys illustrate that student satisfaction with all courses was high; analysis of their open-ended responses and interview data allows us to draw conclusions about specific challenges they faced and elements that helped them succeed. Although the sample of students studied here was somewhat limited, some of these findings may be useful for other cohorts of online students who are similar to the students in the REMOTE cohort, for instance adult learners, working professionals, and students who live in rural areas and in traditional cultural settings.

Balancing work, family, and community commitments with coursework was a significant challenge to the students in the REMOTE program. This was reiterated by all the students interviewed. Four of the seven students who dropped out of the program noted that they simply were unable to juggle all their life commitments along with online coursework. As might be expected, several students encountered significant transitions in life during the two years: marriages, divorces, births, illnesses, deaths in the family, and job changes. These life events resulted in students taking incomplete grades in some semesters. Although some students were able to catch up and complete courses later, some dropped out after falling behind over several semesters of coursework.

REMOTE was structured as a two-year program with no redundancy built into courses. Because it was a pilot program with a limited budget, it was not possible to offer courses multiple times. This tight scheduling caused problems. If students missed a semester of coursework or took incompletes in courses, they had to make it up on their own, with the instructors providing one-on-one assistance. Several students took incompletes and finished courses one or two semesters after the courses were done, but this required instructors to volunteer time to prepare an independent course of study and to grade student work.

Because the amount of engagement and flexibility required for instructors is large, it may be unreasonable to expect this level of commitment. This is an important consideration for program developers. When students, owing to other commitments and life situations that arise, are unable to finish coursework during a semester, ways for them to retake courses should be found. Otherwise, a student who falls behind for several semesters may have no other choice than to drop out of the program because it requires an overwhelming individual effort to finish coursework.

Even the students who successfully completed the program in two years stated that balancing life demands with coursework was challenging throughout. Students often said that face-to-face learning would have been preferable because it would have helped them stay on task and accountable.

One irony for adult learners who enroll in distance learning programs is that they choose an online program because they have limited time to enroll in an on-campus program. However, the reality remains that students need to find or make time for online coursework.

It might help to make students aware that they will need to find strategies to make time to finish coursework. One way to do this might be to address this issue explicitly during their orientation to the program. It can be useful for adult learners, who are juggling full-time day jobs and family commitments after work, to consider their schedules and figure out how to prioritize time for coursework compared with other obligations.

All stakeholders in the program – students, instructors, and administrators – noted the importance of the interactive elements within the program. The initial two-week, face-to-face meeting in Honolulu was highly valued by students. It gave them the opportunity to meet and bond with others in the cohort and with the instructors. Throughout the program, the desire to have more opportunities like this was repeatedly expressed in student comments, both informally and formally.

The students also valued the online discussions with one another during each course. The power of interacting and sharing information about the relevance of course content to their own island contexts was interesting and engaging to students. Although students encountered some technical frustrations with the online discussion board at times (owing to changes in the course management system), the resounding message from students was that interactions with others in the cohort were useful for them. Getting feedback from peers and gaining understanding of the course content as it applied to their fellow students’ island contexts were deemed by students to be motivating, engaging, and informative.

Instructors used Elluminate Live web-conferencing software to offer synchronous online meetings during their courses. These sessions were informal and optional, not built into the program’s framework as an essential component of each course. These web-conferencing sessions allowed students to gather as a group and discuss course content and other course-related issues with one another and with the instructor. Although only a few students attended the Elluminate sessions each time, students did state that they were useful. Students cited conflicts with work times and Internet issues as reasons they were not able to attend. Had the Elluminate sessions been built into courses as a requirement, students may have had the motivation and incentive to make these sessions a priority when making choices amongst their many commitments to jobs, personal lives, and coursework.

The REMOTE project’s budget did not allow more than one face-to-face meeting to be planned. One way to foster interactions within such limitations would be to build synchronous online meetings more formally throughout the program. For example, as mentioned above, instructors could require attendance at synchronous sessions as part of their courses. These synchronous sessions could be used to deliver course content and foster discussion between students and instructors, thereby creating an interactive environment. Sessions required in the context of their classes may have provided added incentive for people to make the time to attend. If such sessions were mandatory and built into courses throughout the program, students would have had consistent opportunities to come together and stay connected with one another and with instructors synchronously in addition to the asynchronous interactions within the online discussion boards.

Consistent support of online learners is another aspect that can make the difference between success and failure for students. As REMOTE students noted, instructor flexibility and understanding were key to their ability to finish courses. In their efforts to support students, instructors often went beyond the expectations for them as instructors, even conducting one-on-one sessions to help students complete coursework after deadlines had passed.

Although this close, individualized attention should not be an expectation placed on instructors, a key lesson for course designers and instructors is to build in instructional activities and assignments that are flexible. The REMOTE instructors noted that after teaching a first course, they changed the amount of content covered and selected more accessible texts for the students. Instructors also incorporated synchronous Elluminate sessions to conduct discussions with students.

Of the five instructors who taught a REMOTE program course, three taught two or more courses. Having instructors who taught more than one course was of great benefit to the program and to the students’ progress. In a graduate-level program, much of the content is built on prior courses. Having a few instructors teach a bulk of the courses helped to maintain consistency of content, of format, and of the process by which courses were taught. The instructors who taught two or more courses got to know the students. These relationships helped them support each student. Because relationships can take longer to establish in an online program, this was a good way for students and instructors to build trust and to understand one another’s teaching and learning styles. Instructors also learned about the students’ cultural contexts and realities over time and were able to design course content that was connected and relevant to the students’ local settings.

Unlike a traditional degree program, in which students attend courses on campus and have the benefit of informally sharing program information with one another, online students do not automatically see the bigger picture of the scope of their programs. REMOTE students also noted the support provided by their advisors and by the program director. The program director provided information to the students on the bigger picture of their two-year program, keeping them abreast of upcoming deadlines and courses and tracking individual student progress.

The advisors, a group of volunteers, helped students write their final theses, serving as one-to-one mentors. Students found these regular communications from the program director and from their advisors useful and motivating. Some noted that this sort of one-on-one communication, coming at some key moment when they were ready to drop out of the program, gave them the push and determination to continue.

Online learners have a variety of personal circumstances and learning preferences. Although it is not possible to foresee all the issues that a particular cohort or program will encounter, it is possible to consider the major challenges that adult learners taking online courses are likely to face and to build in support structures at the start of a program. In a traditional face-to-face degree program, students have the benefit of a structure that comes with being on a campus, interacting at regular intervals with peers, and having informal interactions with faculty and staff. For online learners, specific structures can be designed and implemented to address their needs for information, communication, and interaction. We conclude this paper with a set of recommendations for multiyear degree programs in settings such as the Pacific Islands:

Online learning is indeed a unique opportunity for many people in rural and geographically dispersed settings to further their education. With forethought about the factors that will keep students engaged and the realities of their lives that may impede sustained focus on academic matters, program developers and instructors can create learning environments that help students complete their course of study and earn their degrees.

This project was funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation to the Pacific Resources for Education and Learning, award number S004D080009.

Berkshire, S., & Smith, G. (2000). Bridging the great divide: Connecting Alaska native learners and leaders via “high touch-high tech” DL. In L. Berry (Ed.), Monograph series of the National Association of African American Studies. Houston TX: National Association of African American Studies.

Green, J. C., & Caracelli, V. J. (Eds.). (1997). Advances in mixed-methods evaluation: The challenges and benefits of integrating diverse paradigms. New Direction for Program Evaluation (Vol. 74). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ho, C., & Burniske, R. (2005). The evolution of a hybrid classroom: Introducing online learning to educators in American Samoa. TechTrends, 49(1), 24-29.

Lebec, M., & Luft, J. (2007). A mixed methods analysis of learning in online teacher professional development: A case report. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 7(1), 554-574.

Lincoln, Y. S. (2002, November). On the nature of qualitative evidence. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Sacramento, CA.

Maxwell, J. A. (2004). Causal explanation, qualitative research, and scientific inquiry in education. Educational Researcher, 33(2), 3-11.

McLoughlin, C. (1999). Culturally responsive technology use: Developing an on-line community of learners. British Journal of Educational Technology, 30(3), 231-243.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rao, K. (2007). Distance learning in Micronesia: Participants’ experiences in a virtual classroom using synchronous technologies. Innovate, 4(1), Retrieved from http://www.innovateonline.info/pdf/vol4_issue1/Distance_Learning_in_Micronesia-__Participants%27_Experiences_in_a_Virtual_Classroom_Using_Synchronous_Technologies.pdf

Scriven, M. (1967). The methodology of evaluation. In R. W. Tyler, R.M. Gagne & M. Scriven (Eds.), Perspectives of curriculum evaluation (pp. 39-83). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Scriven, M. (1991). The evaluation thesaurus (4th ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Toth, M., Foulger, T., & Amrein-Beardsley, A. (2008, June 1). Post-implementation insights about a hybrid degree program. TechTrends: Linking Research and Practice to Improve Learning, 52(3), 76-80.

Zepke, N., & Leach, L. (2002). Appropriate pedagogy and technology in a cross-cultural distance education context. Teaching in Higher Education, 7(3), 309–321.

Section I and Section II are closed-ended questions answered on a five point scale (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree)

Section I: Instructor Practices

Section II: Course Content and Instructional Strategies

Section III: Open-Ended Questions