Volume 24, Number 1

Courtney N. Hanny1, Charles R. Graham1, Richard E. West1, and Jered Borup2

1Brigham Young University, 2George Mason University

Despite increased interest in K-12 online education, student engagement deficits and the resulting student attrition remain widespread issues. The Academic Communities of Engagement (ACE) framework theorizes that two groups support online student engagement: the personal community of support and the course community of support. However, more evidence is needed to understand how members of these communities, especially parents, support students in various contexts. Using insights gleaned from 14 semi-structured interviews of parents with students enrolled in online secondary school, this study adds support to the roles identified in the ACE framework by presenting real examples of parents supporting their online students’ affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement. Findings also confirm patterns found in previous research that are not explained using the ACE framework, such as parental advocacy, communication with teachers, and self-teaching. We discuss how a systems approach to conceptualizing the ACE communities allows the framework to more accurately capture parents' perceived experiences within the personal community of support. We also discuss implications for both practitioners and members of students’ support structures.

Keywords: learner engagement, distance education, electronic learning, virtual schools, secondary education, parent role

Enrollment in K-12 online learning continues to increase, despite attrition rates that are higher than those for in-person classes (Freidhoff, 2021). One explanation could be a lack of student engagement (Borup, 2016), defined as a student’s ability and drive to apply themselves cognitively, affectively, and behaviorally to their coursework—something that may be more difficult to develop in online settings due to fewer opportunities for interaction and increased learner isolation (Martin & Bolliger, 2018).

In the Academic Communities of Engagement (ACE) framework, Borup et al. (2020) proposed that student engagement in online courses increases when two communities support students: the course community, which includes teachers, classmates, and other supports within the course, and the personal community, which exists independently of students’ course enrollment. K-12 students’ parents or guardians are primary actors within their personal community of support, as research has shown parental influence is important to student achievement in traditional, in-person classes as well as online courses (Black, 2009; Jeynes, 2007).

The ACE framework also highlights types of support students could receive from their personal communities to increase their affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement, such as academic mentoring, behavior monitoring, and encouragement (Borup et al., 2020). However, limited research exists on specific parental roles within the personal community of support, how those roles appear in various contexts, and how they support student engagement. Without such evidence, researchers lack a foundation to explore the implications of the framework. Additionally, practitioners, parents, and other supportive actors in students’ education may struggle to apply implications built on theoretical underpinnings instead of relatable case studies.

This research sought to more deeply understand the roles parents play in secondary students’ online education through the lens of the ACE framework. Parental roles in the personal community of support are particularly important in online school settings, as parents or guardians are often the adults who are physically present when students are engaging in remote education. Understanding the parental role is therefore an important step in knowing how to assist both students and their support structures in these settings. In exploring this problem, we analyzed parents’ support from the parents’ perspectives to understand how they perceive both their supportive roles and their experiences therein.

The purpose of this review is to (a) briefly introduce the research base studying student engagement, (b) explain what the ACE framework adds to our understanding of student engagement, and (c) review current research regarding parental support roles.

Student engagement has been described as the “holy grail of learning” (Sinatra et al., 2015, p. 1)—an appropriate phrase emphasizing both the importance and elusiveness of the construct. Its importance has been reaffirmed by research linking engagement to student achievement, academic persistence, better mental health, and fewer delinquent behaviors (Wang & Degol, 2014). However, research has also confirmed the construct’s elusiveness, as many can agree on its multidimensional nature but not on the specific dimensions that compose it (Reschly & Christenson, 2012). These disagreements relate to what types of engagement are considered in defining student engagement and what grain, or scope, should be considered as affecting student engagement (Sinatra et al., 2015).

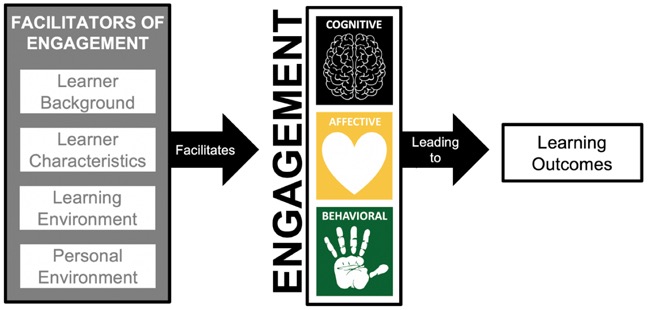

For the purposes of this study, we adopted Borup et al.’s (2020) definition of engagement. Specifically, following a review of the literature, Borup et al. (2020, p. 813) identify and define three dimensions of learner engagement: affective (“emotional energy associated with involvement”), behavioral (“physical behaviors [energy] required to complete course learning activities”), and cognitive (“mental energy exerted towards productive involvement”). For scope, we consider the individual student, as opposed to a school or class, but we attempt to account for the learner’s characteristics and their personal and learner environments, since each of these influences the student’s ability to engage in learning activities (Borup et al., 2020; Figure 1). With engagement, as Reschly, Christenson, and Wylie (2012) summarize, “both the individual and context matter” (p. vi).

Figure 1

Facilitators, Dimensions, and Results of Engagement

Note. Adapted from “Academic Communities of Engagement: An Expansive Lens for Examining Support Structures in Blended and Online Learning,” by J. Borup, C. R. Graham, R. E. West, L. Archambault, & K. J. Spring, 2020, Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), p. 811 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x). Copyright 2020 by Springer Nature.

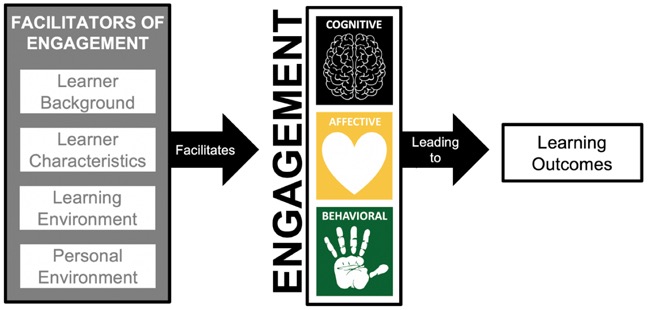

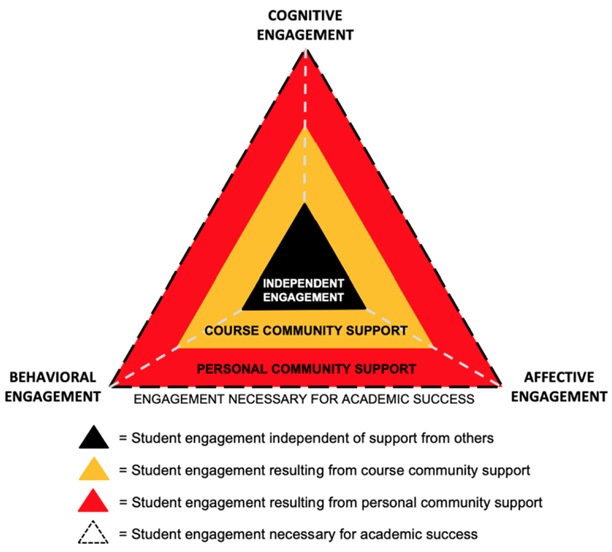

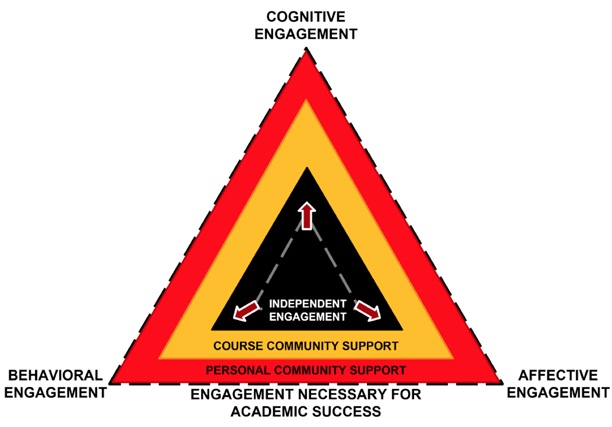

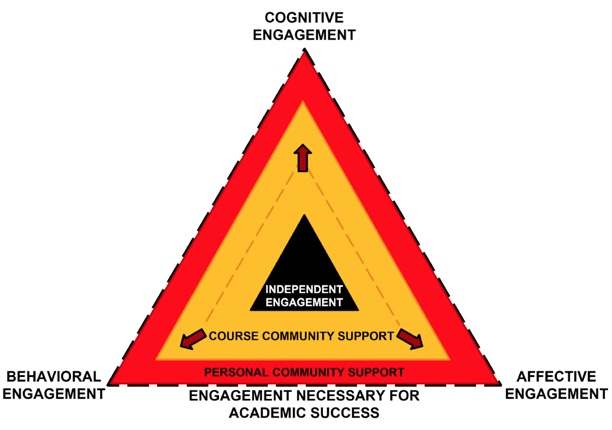

The ACE framework is founded on the theory that others’ support can increase students’ academic engagement. This theory considers the entire system supporting the learner and has ideological roots in Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) ecological theory of child well-being and development and Vygotsky’s (1978) zone of proximal development, which postulates that the level of achievement students can accomplish is greater with the help of others. The ACE framework groups the support actors within Bronfenbrenner’s mesosystem of support into two communities: the personal community of support (i.e., the actors who support a student before, during, and after a specific course) and the course community of support (i.e., the actors associated with the student because of and for the duration of a particular course) (see Figure 2). Given online students’ lack of physical contact with the course community, the personal community—especially the parent(s)/guardian(s)—is of particular importance in online school settings.

Figure 2

Academic Communities of Engagement (ACE) Framework

Note. The support communities help bridge the gap between what the student can do alone (inner black triangle) and what they need for academic success (outer triangle depicted with black, dashed lines). From “Academic Communities of Engagement: An Expansive Lens for Examining Support Structures in Blended and Online Learning,” by J. Borup, C. R. Graham, R. E. West, L. Archambault, & K. J. Spring, 2020, Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), p. 810 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x). Copyright 2020 by Springer Nature.

This section summarizes typical parental support roles in online settings. While some roles serve multiple dimensions, most can be categorized as supporting either affective, behavioral, or cognitive engagement. Hanny (2022) conducted a thorough examination of parental roles and how they fit into the three dimensions of engagement; highlights are given here.

Previous studies have shown several ways parents help their online students emotionally invest in learning. For example, parents help students have a positive academic experience by encouraging and nurturing them (Borup et al., 2019; Borup et al., 2015; Hasler Waters, 2012). They also provide support by motivating students and helping them set goals (Borup, 2016; Curtis & Werth, 2015; Hasler Waters, 2012; Hasler Waters & Leong, 2014; Keaton & Gilbert, 2020).

Parents can inspire behavioral engagement by supporting and enabling student participation in course-based activities. These can be one-time acts, such as providing space to complete schoolwork (Downes, 2013; Novianti & Garzia, 2020), or occasional acts, such as monitoring student work (Borup et al., 2015; Oviatt et al., 2018) and helping with weekly schedules (Hasler Waters, 2012; Oviatt et al., 2018). Similarly, parents can support student participation in extracurricular activities, and for some families, this schedule flexibility is the primary motivation behind enrolling their children in online courses (Harvey et al., 2014). However, behavioral support can also be constant, such as when parents manage student work (e.g., checking every submission for completeness; Borup et al., 2019; Rice et al., 2019) or provide daily organizational support (Hasler Waters & Leong, 2014; Curtis & Werth, 2015).

Parents also help online students cognitively engage in their work. This primarily occurs as tutoring or teaching students required content (Borup & Kennedy, 2017; Keaton & Gilbert, 2020). However, a few studies have reported parents providing cognitive support by assessing student knowledge (Cwetna, 2016; Downes, 2013) and otherwise reinforcing learned content (Hasler Waters, 2012).

Additional roles exist in the literature that do not fit cleanly in the ACE framework. These roles include leveraging external resources (Cwetna, 2016; Rice et al., 2019), communicating with the teacher or school (Borup et al., 2019), analyzing student needs (Downes, 2013; Hasler Waters, 2012), self-teaching content (Curtis & Werth, 2015; Cwetna, 2016), aiding student development (e.g., helping students develop study skills or integrity; Borup & Kennedy, 2017; Hasler Waters, 2012), and advocating on behalf of the student (Franklin et al., 2015; Rice et al., 2019). These roles are important aspects of what parents do within the personal community of support, but the ACE framework does not currently account for them.

While the abovementioned studies provide a view of parental roles in various capacities and environments, additional case studies in varied contexts are needed to develop the transferability of the ACE framework. Just as important as the situations in which the ACE framework explains parental roles are those it cannot explain, as these negative cases may reveal additional insights. Finally, a variety of sources is necessary to understand these roles, including self-reported data from parents of online students.

In this study, we sought to further understand the role of parents in the personal support community as well as the interconnections between parental support, students’ abilities to independently engage, and the support of course communities. In this section, we will describe the school setting and our method for recruiting participants. Then we will describe our methods for data collection and analysis, as well as possible limitations and ethical considerations in our research design.

Participants in this study were parents of students enrolled full-time in a public online secondary school in the Intermountain West region of the United States. We administered a recruitment survey via the school’s regular parent e-mail and selected participants from those who responded based primarily on students’ grade levels and parents’ self-reported involvement levels. Within these strata, we considered other demographic information to recruit diverse experiences and voices.

Sampling limitations include limited transferability of parents’ experiences since we recruited from a single school. Self-selection bias was possible, as parents willing to complete a recruitment survey and commit to an interview are likely more engaged in their child’s education. We did not collect demographic information such as sex and socioeconomic characteristics, so it is unclear if interviewed parents represented a distribution across these and other demographics.

The fully online school served students in grades 7 to 12. Each grade level housed 200 to 300 students, all from within the state. The school website contained an information page encouraging parents to participate in their child’s education but reassuring them that involvement was optional due to low teacher-student ratios. The website also advertised an optional parent-teacher social media connection and regular parent-focused meetings. While the school’s characteristics and approach to parent-school partnerships may limit transferability for this study’s results, it provided an environment in which parents were neither required nor pressured to participate.

We sampled and interviewed 14 parents. The purpose of the 30-45-minute, semi-structured interviews was to reveal parents’ roles and involvement in their students’ online education. Initial questions inquired about parents’ typical roles, parents’ levels of involvement, and how parental roles interacted with other elements of students’ education. However, the semi-structured format allowed for the exploration of themes within parents’ responses.

We analyzed the interview data in two phases. The first phase followed open coding based on Creswell and Poth’s (2018) approach to grounded theory. Open coding was the most appropriate coding approach for this study due to its exploratory and case study nature (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Three researchers formed the data analysis team. We each read one to two interviews, looking for roles that parents described having in their student’s online education. We then discussed the codes we found before analyzing two to four more interviews each. At the next meeting, we combined codes into common categories (axial codes) for use in analyzing the remaining interviews.

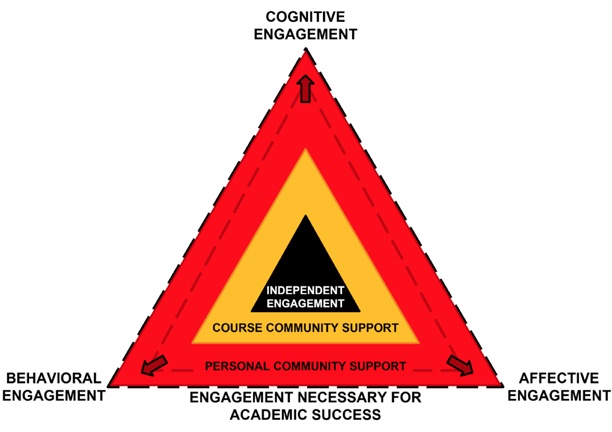

Next, the three researchers met again to discuss the axial codes. While this first set of axial codes was influenced by prior research completed regarding the ACE framework, another underlying coding structure that ran across these axial codes was noticed. While they were not true “selective” codes as defined by Creswell and Poth (2018), these categories acted as another axis by which the codes could be arranged in a matrix (Figure 3). The initial axial codes related to how parents were supporting their students (affectively, behaviorally, or cognitively), but the secondary axial codes reflected patterns in how parents delivered this support, whether directly to the students or by influencing one of the other communities of support.

Figure 3

Matrix Depicting Intersections Between Initial and Secondary Codes

| Initial Axial Codes | ||||

| Affective Roles | Behavioral Roles | Cognitive Roles | ||

| Secondary Axial Codes | Supporting Students Directly | |||

| Increasing the Parent’s Ability | ||||

| Cultivating Student Capability | ||||

| Pursuing Course Community Support | ||||

Intrigued by this second set of codes, we read through the interviews, looking specifically for examples that fit within each box of the matrix. Codes were indexed based on interview number, a subjective rating on the example’s strength, and a rough description or quote indicative of the example. The primary author then organized the strongest and most prevalent examples into a summary of results that was confirmed with the research team and the original interview participants.

In qualitative research, the researchers are considered the “primary instruments” (Merriam, 1992, p. 20); as such, proving the trustworthiness of the data analysis is important. In this study, the researchers were a mix of parents, nonparents, and grandparents, and were biased to some extent in that they believed the role of the parent was important in children’s education. While only one of the researchers has had children enrolled in full-time online education, each has studied student support, student engagement, and online education. As blended and online modalities of education become more prevalent, we believe the role of parents will become more important and that the gap between students with home support and those without will become increasingly apparent.

We sought to strengthen the trustworthiness of our findings through member checks on themes and findings, a diverse selection of authors for this research, and thick description in the form of extensive quotations within the results section. Five parents (36%) responded to member checks; each agreed with our findings. Some provided additional comments, but on all accounts, these addressed topics outside the scope of this paper. The trustworthiness of our results was further strengthened by stratifying research participants and considering each individual’s responses as a form of source triangulation to ensure the findings were not isolated occurrences.

Limitations for this study include the usual transferability concerns of convenience sampling. However, the participants within the school were purposively chosen to collect diverse experiences. Further limitations include nonresponse bias created by lack of survey responses and availability for interviews. Observational and additional case study research may be required to include experiences of parents who are less likely to participate in a study such as this one.

As foreshadowed by Figure 3, this study provided additional evidence for the ACE framework’s personal community of support, including case studies for parental affective, behavioral, and cognitive support mechanisms. However, the data also revealed a phenomenon new to the ACE framework: outside of the ACE roles, parents support students indirectly by influencing the support the student, parents, and course community can each provide. The results first present the direct support offered by parents, then the indirect support they provided. Each section is subdivided by how parents’ actions benefited student engagement.

Parents in this study performed many roles similar to those found in previous research and corresponding to roles of the personal community of support as defined in the ACE framework (Borup et al., 2020; see Figure 2).

In this study, the most represented affective roles parents played were in increasing student interest and motivation and creating an emotionally secure environment. Motivating students when their internal motivation failed is an echo of findings from previous research (Hasler Waters, 2012; Oviatt et al., 2018), but parents also emphasized encouraging students to pursue topics the students found engaging. Parents talked about being a “cheerleader” and “being present” so their children could feel like home was a healthy environment where “school is just a positive thing.” Previous research has mentioned parents needing to love and nurture school-aged children (Borup et al., 2019; Borup & Kennedy, 2017; Borup et al., 2015), but more research could be done on how parents create emotionally healthy home environments when children participate in online school. Research in higher education suggests emotional support may have a greater impact on student outcomes than financial support (Roksa & Kinsley, 2019), underscoring the need for researchers and practitioners to understand the impact and practice of providing emotional support in secondary education.

Results of this study emphasize three ways parents behaviorally support their students: organizing, monitoring, and managing—role tasks found in previous research. However, this study revealed important new nuances.

For example, while many researchers have noted that parents help their online students with organization (Borup, 2016; Downes, 2013), parents in this study emphasized two subcategories: organizing time—such as scheduling and setting routines—and organizing space, by providing materials necessary for participation.

While previous research has described both monitoring (Borup et al., 2015; Curtis & Werth, 2015; Cwetna, 2016; Oviatt et al., 2018) and managing roles (Borup et al., 2017; Hasler Waters, 2012), this study illuminated an important differentiation. Monitoring was an almost universal role task; even the least involved parents expressed thoughts such as this: “My involvement was zero except for checking his grades.” Monitoring included checking on students, occasionally interfering to remove distractions, and tracking student progression. However, parents noted that this “depend[ed] on how [their children were] doing in school. If [they were] not doing well, it is harder, because we do have to be a little bit more strict with how we’re approaching [them].” This inclination sometimes compelled parents more comfortable in a monitoring role to assimilate a managing role, even metaphorically “holding [the student’s] hand” as they worked. Other managing roles included waking students, keeping them on a schedule, and “making sure that they get food throughout the day, meals, and making sure they also get outside.” While former research has noted that monitoring activities “varie[s] greatly across parents” (Borup et al., 2017, p. 7) and flexes based on students’ self-regulation (Borup et al., 2015), this study adds that this spectrum involves more than the time parents dedicate to their student’s academics; it also includes ownership as management of students’ schooling shifts from student to parental control.

Similar to that reported in previous research, most cognitive support roles parents reported involved tutoring (Borup, 2016; Borup & Kennedy, 2017; Keaton & Gilbert, 2020). Parents described this role on a wide spectrum, from editing papers to answering questions to “basically, be[coming] a teacher for seven or whatever hours of the day, because [my child] needed me to be.” Some parents had the academic and experiential background for these roles (e.g., “My degree is in accounting and finance [and] I have a strong science background, too”), but others needed help from external sources (e.g., “For the most part we’ve been able to Google stuff and find videos to help [our students] ... If you [want to] figure something out, you can find it on the Internet”). The varied sources parents report using for their tutoring information give merit to Stevens and Borup’s (2015) concern that parents should be careful in offering cognitive support, as their lack of subject matter expertise may disadvantage students (see also Borup, 2016).

Parents realized they could not always support their children in their schooling as much as they desired, or enough to guide students to academic success. The second major finding of this study was that parental support included more than directly helping students with their academic needs, as presented in the ACE framework. One indirect category of support is when parents increase their capacity to further support students. Instead of acting as the personal community, parents seek to increase the support the personal community can provide in the future (see Figure 4). Like the direct support roles parents play, indirect roles in this category can be grouped into affective, behavioral, and cognitive roles.

Figure 4

Parents Increasing Their Own Abilities: Effect on the Personal Community of Support

Note. To help students reach the engagement necessary for academic success, parents increased the support the personal community could provide. Adapted from “Academic Communities of Engagement: An Expansive Lens for Examining Support Structures in Blended and Online Learning,” by J. Borup, C. R. Graham, R. E. West, L. Archambault, & K. J. Spring, 2020, Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), p. 810 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x). Copyright 2020 by Springer Nature.

Parents reported many indirect affective role tasks, but the most prevalent were increasing parental ability to motivate and changing parental perspectives of success. For example, one parent said she had not yet mastered motivating her son, but she was learning by “just do[ing] things by trial and error.” Another mom echoed these sentiments, saying, “I’m learning how to motivate my kids, what works best.” She then explained she had learned to let her son work independently, but her daughter needed someone present to motivate her. Parents often initially struggled to motivate their children because “some things that worked in the past, maybe, on [another] day doesn’t really work because [the student is] just not in the mood.” It took time to learn effective techniques for offering affective support.

Additionally, parents initially found offering emotional support difficult because their expectations clashed with their children’s desires or capabilities. Previous research has mentioned the parental role of setting expectations (Borup et al., 2019; Borup et al., 2015; Hasler Waters & Leong, 2014), but parents also have the prerequisite task of learning what expectations are appropriate. A parent in a study by Curtis and Werth (2015) also describes this role, calling it a “painful process” (p. 182). In our study, a mother explained,

I’ve had to learn that not everyone was like me ... Her [the student’s] talents and interests are so different from mine ... and so just learning to appreciate that her school experience is going to be different from mine and that’s okay and her grades are going to be different from mine and that’s okay.

Working to understand and change her perspective helped this mother situate herself to better motivate and encourage her daughter.

The most prevalent way parents built their capacity to offer behavioral support was rearranging their schedules to be present while their child worked. Research has shown parents view physical presence as a supportive role (Curtis & Werth, 2015; Hasler Waters & Leong, 2014). Some parents found it sufficient, and had the flexibility, to change the hours they worked professionally. For example, one parent said, “[I] ended up starting my day super early so that I could get a big chunk of work done before he was up and going, and then I would be available” (for another example, see Hasler Waters, 2012). Other parents quit professional work to increase their availability. One mom was working and attending evening classes at a local college when she moved her children to online school. She recounted, “When we made the decision to go online, that made the decision for me to stay at home.” She left her job to be present with her students during the day and continue her own schooling at night.

Parents’ indirect cognitive engagement support roles frequently centered around a need for direct cognitive roles. Two frequent scenarios were (a) students requiring tutoring, for which parents needed to refresh their memory on a topic or teach themselves with the course resources, and (b) students soliciting help with an assignment, for which parents needed to learn to navigate software, such as a learning management system. One parent commented that online school facilitates parents’ ability to learn content for tutoring their children, because “if I need to help them ... I can watch and do the materials. As opposed to a brick-and-mortar school where ... they bring homework and I was like, ‘sorry can’t help you, you don’t have a textbook.’” Other studies have also noted that parents watch students’ class sessions before tutoring their students (Curtis & Werth, 2015; Cwetna, 2016).

In addition to parents increasing their ability to support their students, they also indirectly supported students by increasing students’ capability to help themselves (see Figure 5). By teaching students to be more independent in the future, parents often found their role in students’ personal community of support could decrease.

Figure 5

Parents Cultivating Student Capability: Effect on Independent Engagement

Note. To help students reach the engagement necessary for academic success, parents increased students’ ability to independently engage. Adapted from “Academic Communities of Engagement: An Expansive Lens for Examining Support Structures in Blended and Online Learning,” by J. Borup, C. R. Graham, R. E. West, L. Archambault, & K. J. Spring, 2020, Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), p. 810 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x). Copyright 2020 by Springer Nature.

As a counterpart to monitoring and managing, some parents taught students to create schedules and manage assignment expectations independently. This usually involved more work upfront—parents walked students through processes, gave them organizational tools, and consistently set expectations that they needed to monitor themselves. While this support did not directly impact students’ immediate success in specific classes, it gradually allowed parents to reduce direct behavioral roles without compromising academic success. Interestingly, parents did not always attribute this act to supporting academic success; instead, they were helping students “be prepared to be out on their own.” Previous research supports this finding as parents report feeling a duty to teach students “how to learn” (Hasler Waters, 2012; see also Borup et al., 2015; Hasler Waters et al., 2018).

Parents increased the long-term affective independent engagement of their children by helping them become emotionally resilient. One parent repeatedly taught the mantra “I just haven’t learned this yet” to help her son overcome his frequent frustration in education and sports. Another parent described helping her daughter develop the perspective that effort in school affects opportunities to attend desired college programs. One mother allowed her high-achieving child to gain this perspective by experience; she stated, “You have to let kids fail [struggle] so they can learn.” This mother deliberately watched her daughter’s progress from afar, allowing her to work through obstacles and intervening only occasionally. Unlike establishing high expectations (Borup et al., 2019; Borup et al., 2015; Hasler Waters & Leong, 2014), giving perspective increases intrinsic motivation and students’ future ability to independently engage.

A final indirect role clarified by this research was the support parents offered students by engaging with and helping to expand the influence of the course community (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Parents Pursuing Course Community Support: Effect on Course Community of Support

Note. To help students reach the engagement necessary for academic success, parents increased the support the course community was providing. Adapted from “Academic Communities of Engagement: An Expansive Lens for Examining Support Structures in Blended and Online Learning,” by J. Borup, C. R. Graham, R. E. West, L. Archambault, & K. J. Spring, 2020, Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), p. 810 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x). Copyright 2020 by Springer Nature.

This study is not unique in noting that participants actively chose to switch their children from traditional to online school environments (Borup & Stevens, 2016; Curtis & Werth, 2015). Usual reasons for this choice confirmed those noted in previous research (Borup & Stevens, 2016): a perceived deficit in the local traditional school, a family need, or, in the case of previously homeschooling parents, a perceived deficit in their own support. However, previous research has not acknowledged that entirely changing the course community of support is a primary task parents take on in helping their children receive the support necessary for academic success. Many parents spent extensive time researching school environments, experimenting with school systems, and asking for references from friends and family in trying to fulfill this role.

Parents also played a role in connecting students to resources and support offered by the school. Especially because students were physically distant from their teachers, parents often redirected questions or concerns from the student, asking if they had contacted the teacher for support or reminding them to e-mail the teacher during office hours. Parents reported the importance of reading school communications so that both they and their children could be informed of school programs and other available resources. Cwetna (2016) notes that parents “make sure their child gets help, whether it be from the parent, teacher, or another resource” (p. 94). When schools make resources easy for parents and students to find, parents can support student engagement by helping students access these resources.

In addition to ensuring students’ awareness of school resources, parents also occasionally advocated with the school to increase awareness of students’ needs. This was especially true for parents of students with disabilities and parents whose children struggled with specific subjects. Researchers studying these populations often identify advocate as an important role (Franklin et al., 2015; Rice et al., 2019). However, this study adds that advocacy is also important when students are enrolled in online and traditional schools simultaneously, as some physical schools were unaccustomed to the policies involved in dual enrollment, necessitating parental involvement to ensure students were not penalized for their online school enrollment.

This study has provided additional evidence supporting the ACE framework and identified patterns in past literature’s roles that did not neatly fit into the ACE framework, such as advocating and aiding student personal development. With this expanded view of the functions of the personal community of support comes important implications for research and practice.

The ideological background for the ACE framework is founded in part on Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) ecological systems theory—that is, the idea that social interactions cannot be studied as individual pieces but must instead be studied within the systems in which they occur. Applying this ideology to the present study, student engagement cannot only be studied from the sole perspective of students, teachers, or parents but rather in terms of the interactions among the three.

The ACE framework currently depicts interactions, but only those between the individual community actors and the student or, more precisely, their interactions with the student’s engagement (referred to as an egocentric approach in social network analysis; see Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). This study suggests that the ACE framework could be used more broadly to analyze the interactions between the various actors and how these interactions enhance or deter online student engagement. It further suggests that parental roles move beyond direct interactions with a student’s engagement in a specific course. Additional research could study whether the student, the course community, or other actors within the personal community also have indirect roles in supporting student engagement. Research could also triangulate these self-reported results with evidence from teachers and students and analyze the respective effects of indirect and direct roles on student engagement.

Another aspect of studying student engagement as a system is understanding that students are not the only actors that have context to consider. Parents, as the target of this research, also have individual backgrounds impacting the amount and type of support they provide. Parents make decisions and hold different roles based on these contexts. Additional research could study the motivations and contexts of parents to better understand parents’ desires and obstacles in providing both direct and indirect support. In this study, parents interacted not just with teachers but with the school itself. This indicates the course community also brings the context of existing within a larger school community. Interactions between this community and the individual course communities, as well as the personal community, may also shed light on the support students can receive from various support actors.

While implications for the various community actors are vast and nuanced by context, practitioners, parents, and students can all benefit from research surrounding student engagement and academic success.

The importance of parents in the personal community of support is expanded when they become the supervising adult in their student’s education, as made evident during the COVID-19 pandemic (Novianti & Garzia, 2020). This research revealed that while parents almost universally accepted and filled many roles, some stumbled upon roles they did not anticipate. For example, multiple parents were surprised when they realized they could move their students out of brick-and-mortar school. Parents also discovered that if they invested time into understanding students’ needs, preparing themselves to support students and delegating responsibility to students, they had fewer direct supportive roles. Borup et al. (2013) found the amount of time parents were involved in supporting student schoolwork was not directly correlated with student academic success, which they attributed to parents becoming more involved after students fall short. Based on our findings, we agree that, in these situations, monitoring often changes to managing. However, this change involves not only an increase in parents’ time but also in parental control of students’ academic progress. This increase in control potentially decreases student ownership over their own work and may negatively affect students’ long-term academic engagement.

While the parents in this study strove to improve their own abilities, it is important to remember that most parents of secondary students have never attended online school due to its recently becoming a mainstream option. Like families of first-generation college students that struggle in knowing how to offer support (Irlbeck et al., 2014), parents who never attended online school may need help understanding how to best support their children in online school. Additionally, while the increased availability of subject-specific content for parents enables them to perform direct cognitive support in ways more similar to those attributed to teachers (Borup et al., 2020), such increased confidence without formal instructional training may prove problematic if it leads to parents trying to replace the teacher as the content matter expert (Stevens & Borup, 2015).

Practitioners might benefit from knowing that, in this study, even in a school that emphasized student independence, almost all parents held an active role. While the course community supports students directly, practitioners can develop indirect support systems to help parents in their efforts to support students. Many parents noted the importance of open, regular communication with the school and teachers in helping them provide behavioral support; it may also be helpful to provide resources for parents giving affective and cognitive support as well. This can be as simple as making course materials available for parents in order to avoid parental reliance on YouTube and other external sources for tutoring support. Organizing parent help groups, in which parents can trade advice on effective strategies for helping online students, could also be helpful. Practitioners could lighten their supportive load in the same way parents do: by increasing student ability. For example, online schools could provide student training and templates for organization, making them available to parents who may also be helping students with self-development.

The importance of practitioner support may depend on the household. For example, parents in this study often increased the personal community’s indirect support by rearranging or reducing professional work schedules. However, some parents may lack the flexibility and financial means to use these strategies. Parents sometimes struggled to navigate school software, an even more difficult task for parents doing so in a second language. Parents with multiple children attuned to their students’ needs to prioritize their involvement with the most dependent child, but this strategy may leave other children unsupported. Practitioners should seek awareness of students’ and parents’ greater contexts so they can provide increased support, whether directly for the student or indirectly by mentoring parents about the demands of online school, the needs of their students, and the resources available for support.

In conclusion, the ACE framework is a valuable depiction of student engagement support structures, with many of the roles currently held by parents nicely fitting within its umbrella. However, by using the framework as a tool to analyze the networks and interactions between the communities of support, we have gained a more complete view of how student support plays out in real contexts. What we lose in parsimony, we gain in ability to use the framework to capture the experiences of those supporting student engagement and, therefore, to understand and influence student academic success.

Black, E. W. (2009). An evaluation of familial involvements’ influence on student achievement on K-12 virtual schooling (Publication No. 3367406) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/openview/d97ed5dad5b56aa10611a18d4c95c664/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

Borup, J. (2016). Teacher perceptions of parent engagement at a cyber high school. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 48(2), 67-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2016.1146560

Borup, J., Chambers, C., & Srimson, R. (2019). Online teacher and on-site facilitator perceptions of parental engagement at a supplemental virtual high school. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20(2), 79-95. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1214394

Borup, J., Chambers, C. B., & Stimson, R. (2017, September 28). Helping online students be successful: Parental engagement. Michigan Virtual University. https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/helping-online-students-be-successful-parental-engagement/

Borup, J., Graham, C. R., & Davies, R. S. (2013). The nature of parental interactions in an online charter school. American Journal of Distance Education, 27(1), 40-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2013.754271

Borup, J., Graham, C. R., West, R. E., Archambault, L., & Spring, K. J. (2020). Academic communities of engagement: An expansive lens for examining support structures in blended and online learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), 807-832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x

Borup, J., & Kennedy, K. (2017). The case for K-12 online learning. In R. A. Fox & N. K. Buchanan (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of school choice (pp. 403-420). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119082361.ch28

Borup, J., & Stevens, M. (2016). Parents’ perceptions of teacher support at a cyber charter high school. Journal of Online Learning Research, 2(3), 227-246. http://www.learntechlib.org/p/173212/

Borup, J., Stevens, M. A., & Waters, L. H. (2015). Parent and student perceptions of parent engagement at a cyber charter high school. Online Learning, 19(5), 69-91. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1085792

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513-531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Chapter 8: Data analysis and representation. In Q ualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed., pp. 182-200). Sage Publications. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-inquiry-and-research-design/book246896

Curtis, H., & Werth, L. (2015). Fostering student success and engagement in a K-12 online school. Journal of Online Learning Research, 1(2), 163-190. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1148836

Cwetna, K. G. (2016). Real parenting in a virtual world: Roles of parents in online mathematics courses [Doctoral Dissertation, Georgia State University]. https://doi.org/10.57709/8584504

Downes, N. (2013). The challenges and opportunities experienced by parent supervisors in primary school distance education. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 23(2), 31-42. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1061557

Franklin, T. O., Rice, M., East, T. B., & Mellard, D. F. (2015, November). Parent preparation and involvement. The Center on Online Learning and Students with Disabilities. http://www.centerononlinelearning.res.ku.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Superintendent_Topic_2_Summary_November2015.pdf

Freidhoff, J. R. (2021). Michigan’s K-12 virtual learning effectiveness report 2019-20. Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute. https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/michigans-k-12-virtual-learning-effectiveness-report-2019-20/

Hanneman, R. A., & Riddle, M. (2005). Introduction to social network methods. University of California, Riverside. http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/

Hanny, C. N. (2022). Conceptualizing parental support in K-12 online education. (Publication No. 9394) [Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University]. BYU Scholars Archive. http://hdl.lib.byu.edu/1877/etd12031

Harvey, D., Greer, D., Basham, J., & Hu, B. (2014). From the student perspective: Experiences of middle and high school students in online learning. American Journal of Distance Education, 28(1), 14-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2014.868739

Hasler Waters, L. (2012). Exploring the experiences of learning coaches in a cyber charter school: A qualitative case study (Publication No. 3569079) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Hawai’i at Manoa]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/openview/4633f6308b456602110095858a37d411/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

Hasler Waters, L., Borup, J., & Menchaca, M. P. (2018). Parental involvement in K-12 online and blended learning. In R. E. Ferdig & K. Kennedy (Eds.), Handbook of research on K-12 online and blended learning (2nd ed., pp. 403-422). Carnegie Mellon University: ETC Press. https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/6686813

Hasler Waters, L., & Leong, P. (2014). Who is teaching? New roles for teachers and parents in cyber charter schools. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 22( 1), 33-56. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/112373/

Irlbeck, E., Adams, S., Akers, C., Burris, S., & Jones, S. (2014). First generation college students: Motivations and support systems. Journal of Agricultural Education, 55(2), 154-166. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2014.02154

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Urban Education, 42(1), 82-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085906293818

Keaton, W., & Gilbert, A. (2020). Successful online learning: What does learner interaction with peers, instructors and parents look like? Journal of Online Learning Research, 6(2), 129-154. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1273659

Martin, F., & Bolliger, D. U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning, 22(1), 205-222. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092

Merriam, S. B. (1992). Qualitative research and case study applications in education: Revised and expanded from case study research in education. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Novianti, R., & Garzia, M. (2020). Parental engagement in children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Teaching and Learning in Elementary Education, 3(2), 117-131. https://doi.org/10.33578/jtlee.v3i2.7845

Oviatt, D. R., Graham, C. R., Borup, J., & Davies, R. S. (2018). Online student use of a proximate community of engagement at an independent study program. Online Learning, 22(1), 223-251. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1153

Reschly, A. L., Christenson, S. L., & Wylie, C. (2012). Front Matter. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. i-xxvii). Springer. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/bfm:978-1-4614-2018-7/1?pdf=chapter%20toc

Roksa, J., & Kinsley, P. (2019). The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students. Research in Higher Education, 60(4), 415-436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9517-z

Rice, M., Ortiz, K., Curry, T., & Petropoulos, R. (2019). A case study of a foster parent working to support a child with multiple disabilities in a full-time virtual school. Journal of Online Learning Research, 5(2), 145-168. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/184933/

Sinatra, G. M., Heddy, B. C., & Lombardi, D. (2015). The challenges of defining and measuring student engagement in science. Educational Psychologist, 50(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.1002924

Stevens, M., & Borup, J. (2015). Parental engagement in online learning environments: A review of the literature. Advances in Research on Teaching, 25, 99-119. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-368720150000027005

Wang, M. T., & Degol, J. (2014). Staying engaged: Knowledge and research needs in student engagement. Child Development Perspectives, 8(3), 137-143. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12073

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, Ed.). Harvard University Press. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674576292

"Someone in Their Corner": Parental Support in Online Secondary Education by Courtney N. Hanny, Charles R. Graham, Richard E. West, and Jered Borup is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.