Volume 23, Number 4

Tsige GebreMeskel Aberra and Mogamat Noor Davids

University of South Africa (UNISA)

This study assessed students’ level of satisfaction with the quality of student support services provided by an open distance e-learning (ODeL) university in Ethiopia. The target population was doctoral students who had been registered at the ODeL university for more than a year. To conduct a quantitative investigation, data were collected by means of a 34-item six-dimensional standardized questionnaire. Data analysis methods included linear as well as stepwise regressions. Using the gaps model as the theoretical framework, findings showed that the doctoral students were dissatisfied with four aspects of the student support services, namely supervision support, infrastructure, administrative support, and academic facilitation. In contrast, students were satisfied with the corporate image (reputation) of the ODeL university. For this ODeL university to play an effective role that coheres with the country’s socio-economic development plan, more attention should be given to the provision of supervision support, as there was strong dissatisfaction with this. The university could also build on or leverage aspects of their corporate image, for which there was strong satisfaction. Doing so will help the university make ongoing contributions and strengthen its commitment to the field of higher education and human capacity development in Ethiopia.

Keywords: doctoral students, gaps model, ODeL, satisfaction, service quality, student support

The socio-economic developmental goals of countries around the world are realised through the continued growth of human resource capacity. The higher education sector has a decisive role to play, especially as its contribution to human capital development, which is expected to bring about positive and meaningful changes in countries’ socio-economic conditions (Van Deuren et al., 2016). In its effort to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), the government of Ethiopia emphasised human capital development as one of its key strategies. The government has been working towards ensuring the availability of requisite human resource and skills capacity at all levels of expertise. The Ethiopian National Science Policy and Strategy identifies human capacity development “as a major driving force for the progress and advancement of a nation” (Ministry of Science and Higher Education [MoSHE], 2020b, p. 18).

For Ethiopia to become “the African Beacon of Prosperity by 2030” (MoSHE, 2020a, p. 10), higher education will be on the frontier of development. In this regard, the Ethiopian Ministry of Science and Higher Education has been working aggressively towards producing 5,000 PhDs within five years (2021-2025). This plan called for universities to work collaboratively, sharing resources to support doctoral students. The facilities needed for PhD studies can be enriched through the development of partnerships, as well as networking with local and international academic and research institutions. Experts from industry, academia, and the diaspora should form part of the supporting structure. These plans were intended to meet the national reform objectives in which doctoral education has a role to play. In turn, doctoral graduates were expected to have a strong impact on the socio-economic development of Ethiopia by contributing towards an improved standard of living for all its citizens (MoSHE, 2020a).

With this developmental objective in mind, the 51 public universities in Ethiopia have been classified into three categories—research, applied science, and comprehensive universities. The research universities were meant to focus on scientific research by offering masters’ and PhD programmes. To do so, these universities established research centres to collaborate among one another, and with international academic institutions. Staff members at these universities were expected to conduct research and publish in internationally recognized academic journals. This expectation differed from universities that prepared professionals to practise in the world of work (e.g., business and industry) and do research supported by their links to institutions and indusandtries. The comprehensive universities in turn were expected to teach undergraduates, and to conduct research as academic institutions, (Sisay, 2020; Wodwossen, 2020).

For the past decade and a half, Open, Distance, and e-Learning (ODeL) has been successfully supporting the Ethiopian higher education landscape as it is offered by international universities that operate in collaboration with public and private higher education institutions. This sector has arguably contributed positively towards the human capacity development of the country. However, the authors of this article, who are employed at one of these ODeL institutions operating in Ethiopia, were aware of grassroots rumblings from both students and lecturers that may cause reputational damage, if not addressed timeously. For example, the quality of service that the universities have provided to postgraduate students is of major concern and should not be taken for granted. This study focused on identifying Ethiopian students’ levels of satisfaction and dissatisfaction in relation to the support services provided by one of the ODeL universities.

In an ODeL system, student support services play a pivotal role, providing students with the necessary academic and emotional support during their doctoral journey (Ngaaso & Abbam, 2016). While it is always beneficial to support research students through academic workshops and seminars, supervisors’ support should be responsive to students’ needs. For example, timely, constructive, and consistent feedback to students’ submissions has been shown to keep the momentum and tempo of their work steady and increases student satisfaction (O’Shea et al., 2015; Paposa & Paposa, 2022).

Students’ feelings of loneliness could be managed by offering guidelines, and motivating them to join electronic networks and groups with students of similar academic interest. When students worked in groups, their belongingness to the university was heightened, which may have increased their sense of satisfaction (Dzakiria, 2005). A lack of student support may have resulted in lower success rates and increased dropout rates (Sibai et al., 2021). Hence, student support services served as anchors, particularly in ODeL institutions (Southard & Mooney, 2015).

In addition to the quality of the academic and emotional support provided to students, the concept of satisfaction was integral to the research reported in this article. Satisfaction has been understood as a key aspect of service quality (Teeroovengadum et al., 2016). From a marketing perspective, satisfied customers were ambassadors to sell the services provided by the business (Dann, 2008). Similarly, in the higher education ODeL sector, students were cared for because they were regarded as customers of and ambassadors for their affiliated institution. Students have been perceived as customers of higher education because major services like library facilities, course materials, and supervision systems were prepared specifically for students. They pay fees that have sustained higher education institutions (Tsige, 2016; Farooq et al., 2019). It is therefore imperative that educational service providers continuously strive towards satisfying and retaining students throughout their journey from application for admission until graduation (Jain et al., 2010).

This study investigated whether support services offered to doctoral students by an ODeL university satisfied their expectations. We designed a quantitative methodology with a questionnaire for data collection. The results from the responses to the questionnaire have been presented in the findings section below.

The gaps model (Parasuraman, et al., 1985) was adopted as an analytical framework, because it was argued that students’ complaints and apparent dissatisfaction resulted from the gap between students’ expectations and their actual experiences.

Considering the need for doctoral throughput to achieve Ethiopia’s developmental objectives, the higher education sector should be proactive in identifying potential obstacles that may derail the production of doctorates. To this end, this study

The rest of this article explores studies related to the research problem, the theoretical framework used, a brief description of the methodology, the findings, and discussion. The article ends with conclusions and recommendations.

The relationship between service quality and satisfaction has been a concern in various service-providing industries, including (a) education, (b) health, (c) hospitality and tourism, and (d) the police service. The main purpose for discussing service quality and its relationship with satisfaction has been to identify the drawbacks of the service provider and find solutions to overcoming such challenges. This process of assuring quality has helped companies retain existing customers and attract new ones (Nyenya & Bukaliya, 2015).

Since this study focused on service quality and satisfaction with particular reference to doctoral students enrolled in an ODeL university, we reviewed literature from the field of education. Accordingly, the literature focused on students’ satisfaction and/or dissatisfaction with the quality of services offered by the educational service providers in different countries.

Using the SERVQUAL model, Sibai et al. (2021) undertook a study on the relationship of service quality with satisfaction. They collected data from 189 medical college students in Saudi Arabia and analysed data by means of descriptive statistics and regression analysis. The authors found that the students were dissatisfied with three dimensions of SERVQUAL, namely responsiveness, empathy, and tangibles. Similarly, Wael (2015) used SERVQUAL to collect data from students of all faculties at Pavia University, located in Italy. The study found that students’ satisfaction was low on all five dimensions (i.e., tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy) because the students’ experiences were less than their expectations of service quality. On the other hand, Napitupulu et al. (2018) measured student satisfaction with service facilities by using a 14-item, 2-dimensional questionnaire. They found that expectations were higher than experiences, and concluded that the services on offer by the XYZ University were not yet satisfactory to the users. A similar finding (i.e., negative relationship between service quality and satisfaction) was recorded by Khalil et al. (2018) who identified the extent of student satisfaction with service quality dimensions. Their study population was private schools in Egypt where 900 students were selected to fill out a questionnaire on SERVQUAL with the concept of institutional image as an added dimension. Their findings showed that among the five dimensions of SERVQUAL, reliability and responsiveness had a negative relationship with satisfaction. Datt and Singh (2021) studied students, graduates, and dropouts who were exposed to the different e-services offered by a university in India. They sent an e-questionnaire to this purposely selected group and used descriptive statistics (percentages) to analyse the results. They found that the respondents were dissatisfied with the (a) mobile application that was employed by the university, (b) grievance-handling system, (c) inaccessibility of the e-learning portal, and (d) unavailability of video-recorded lectures.

As opposed to the above, positive relationships between service quality dimensions and satisfaction were recorded in many studies, including Kara et al. (2016) who identified service quality dimensions related to student satisfaction. A 70-item, 5-point Likert scale questionnaire was distributed to 1,062 undergraduate students at eight public universities in Kenya. The study found that service quality and student satisfaction were statistically significantly and moderately related in seven of the ten dimensions. Student satisfaction was positively related to six quality dimensions, namely (a) quality of teaching facilities, (b) availability of textbooks, (c) administrative service quality, (d) reliability of university examinations, (e) perceived learning gains, and (f) quality of students’ welfare services.

Ngaaso and Abbam (2016) also showed positive relationships between student support service quality and satisfaction. Respondents were 564 distance learning students at the University of Education in Ghana who filled out a four-point Likert scale questionnaire. The following were found to be the most important contributors to students’ satisfaction: (a) self-check questions and exercises at the end of each chapter, (b) readiness of help desk staff to give the necessary assistance, and (c) the knowledge and skills of professors and tutors. On the other hand, Khalil et al. (2018), found tangibles, empathy, and assurance were positively related with satisfaction. In addition, school image was found to have a positive relationship with satisfaction, and contributed the biggest share in explaining satisfaction.

Ntabathia (2013) also showed positive relationships between service quality and satisfaction, after collecting data using HEdPERF, a 41-items scale with 5 dimensions, distributed to 180 private university students in Nairobi, Kenya. The findings showed that the dimensions of reputation (i.e., university’s image in the eyes of the public and employers) and programme issues (i.e., the importance of offering a variety of reputable academic programmes in a flexible manner) had statistically significant relationships with satisfaction. Secreto and Pamulaklakin (2015) focused on ODeL students’ level of satisfaction with the Open University of Philippines student portal, developed for the purpose of facilitating students’ academic journey. They sent a 14-item online survey questionnaire to undergraduate and postgraduate students at the university. They deliberately addressed students who had experienced both manual and online systems for registration, making payments, checking grades, accessing the online library, contacting their course lecturers, and the like. Generally, students were more satisfied with the online system, which they said was characterized by “reliability, accessibility, simplicity and clarity of instructions” (Secreto & Pamulaklakin, 2015, p. 40).

Similarly, Sembiring (2015) distributed a questionnaire to distance education graduates from Terbuka University in Indonesia to determine if there were any correlations between the five dimensions of SERVQUAL and satisfaction. This study showed that reliability, empathy, and responsiveness were directly related with the graduates’ satisfaction when they were students at the university. Sembeiring recommended that the university focus on continuing to improve on these three dimensions of service quality so that satisfaction, which in turn had a direct impact on student retention and persistence, would be secured.

As indicated, various studies on student satisfaction were conducted with both negative and positive findings, and they provided concrete ideas on the relationship between the service quality and satisfaction. In a similar manner, this study was conducted to determine the level of student satisfaction with the different student support services offered to doctoral candidates registered at an ODeL institution. There is scant literature on doctoral students’ satisfaction, with specific reference to ODeL mode of learning in Ethiopia and other African countries. Our study contributed to addressing this knowledge gap.

This study used the gaps model (Parasuraman, et al., 1985) as an analytical framework so as to identify gaps between expectations and experiences in service quality. Examining the gaps between these two constructs served a diagnostic purpose, revealing the causes of customers’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction with services and highlighting ways to sustain and improve customer satisfaction.

According to the gaps model (Parasuraman, et al., 1985), if services are found to be better than expected, then customers are satisfied. If customers’ experiences are the same as their expectations, this is mere satisfaction. However, if customers’ expectations exceed their experiences of the services on offer, they may experience dissatisfaction. In measuring this phenomenon, the authors of the model developed 10 service quality determinants from an exploratory study that involved different service-providing firms.

In a further study, the authors (Parasuraman et al., 1988) elaborated on the gaps model for measuring service quality by using empirical research on different service providers. Rigorous statistical methods, including Cronbach’s alpha and factor analysis, were used to test and re-test the model. The procedures assisted in reducing the dimensions of service quality from 10 dimensions to 5 by removing redundancies and combining the similar ones. Test items were generated for each dimension. This resulted in a 22-item questionnaire that elaborated the following five dimensions (Parasuraman et al., 1988, p. 23):

The target population for this study was 465 doctoral students in an ODeL university operating in Ethiopia. The sample was selected through convenience sampling. The students were reached by telephone and asked to consent to and participate in the study. Those who agreed were asked for their private e-mail address to which the questionnaire, that is shown in Appendix I, was sent. As a result, 260 questionnaires were collected. Out of these, only 227 were suitable for analysis (N = 227). Of the 227 respondents, 85% were aged 31 to 50 years, 96% were males, and 83% were married. The respondents were enrolled in various disciplines offered by the university, including education, health, business, agriculture, and science.

The questionnaire was standardised by means of (a) inter-rater reliability (K = 0.89); (b) content validity (I-CVIs ranging from 0.88-1.00 and S-CVI = 1.00); (c) pilot testing to identify redundant items; (d) Cronbach’s alpha (α ranging from 0.76-0.90 for the five dimensions); and (e) factor analysis procedures (factor loadings ranging from 0.475-0.819) in subsequent orders as stated here. These procedures, the last two of which are shown in appendix II, contributed towards the questionnaire’s validity and reliability. The result of this rigorous process was a 34-item Likert scale questionnaire. The five dimensions of support served as independent variables, whereas one dimension, satisfaction, served as the dependent variable. Table 1 shows each dimension and its meaning in the context of this study.

Table 1

Definitions of Study Dimensions

| Dimension | Meaning as used in this study |

| Supervision support | Timely and constructive feedback should be provided by supervisors in the process of guiding students to facilitate their academic journey. |

| Infrastructure | Provisions the university makes available to students in physical as well as soft formats (e.g., online library, ICT services). |

| Administrative support | Support schemes that relay valuable information and assistance regarding processes students should follow during application for admission and registration. |

| Academic facilitation | Academic support programmes that fast-track students’ academic progress to decrease dropouts and increase graduation rates. |

| Corporate image | Issues related to how stakeholders evaluate the status or reputation of the university. |

| Satisfaction | Students’ feelings of fulfilment that result from their perception of the services the university provides. |

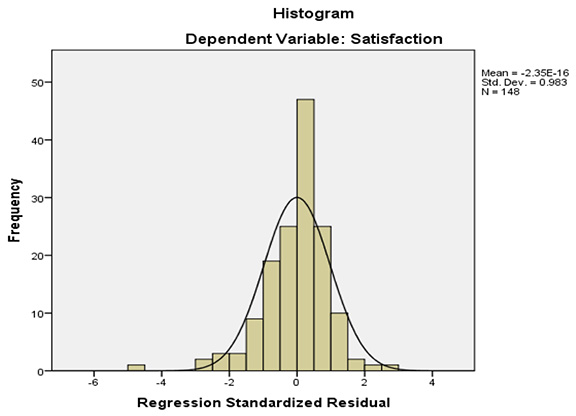

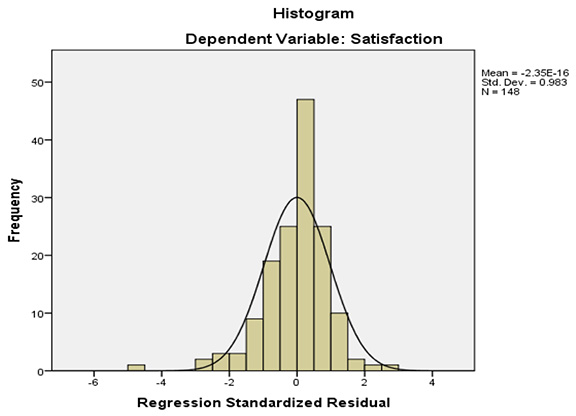

The data were found to be normally distributed; the peak fell on the mode of the normal curve as shown in Figure 1. Such normal distribution assures that data can be analysed using inferential statistics.

Figure 1

Data Distribution

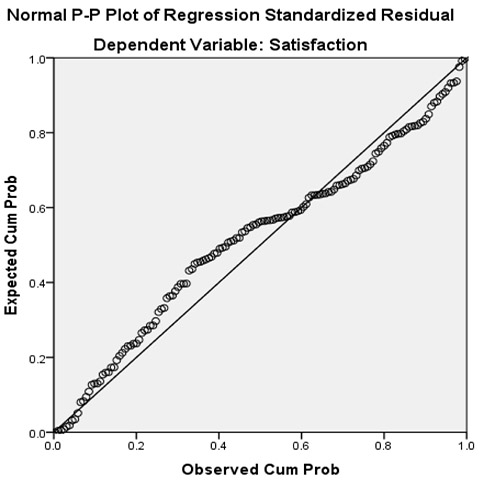

In addition, as shown in Figure 2, the linearity of the data was observed before running linear regression, and the data were found to be close to the linear line. This also ensures the data is fit to be analysed through the regression model.

Figure 2

Linearity of the Relationship Between Satisfaction and the Independent Variables

The relationship between each student support dimension and satisfaction was observed by using simple (linear) regression. Moreover, to determine which dimension(s) among the five better explain(ed) students’ satisfaction, stepwise regression was used to filter out and indicate which dimensions contributed most.

Using average scores of the doctoral students’ expectations and experiences of service quality, the linear regression method was used to observe the relationship of each dimension with satisfaction for the first four dimensions. As shown in Table 2, each of the four dimensions of service quality (i.e., supervision support, infrastructure, administrative support, and academic facilitation) had significant negative relationships with satisfaction whereas corporate image and satisfaction were significantly and positively related.

Table 2

The Relationship Between the Five Dimensions and Satisfaction

| Independent variable | Dependent variable: Satisfaction | ||||

| Beta | t value | p value | R | R2 | |

| Supervision support | -0.091 | -5.544 | 0.001 | 0.377 | 0.138 |

| Infrastructure | -0.045 | -1.986 | 0.048 | 0.141 | 0.015 |

| Administrative support | -0.118 | -3.762 | 0.001 | 0.251 | 0.058 |

| Academic facilitation | -0.110 | -2.542 | 0.012 | 0.175 | 0.026 |

| Corporate image | 0.439 | 16.412 | 0.001 | 0.744 | 0.552 |

As shown in Table 2, supervision support explained 14% of the variance in satisfaction; the relationship between the two variables was significant and negative (R2 = 0.138, F(1,185) = 30.739, p < 0.001). Regarding infrastructure and satisfaction, the relationship was significant and negative. Infrastructure explained only 1.5% of the variation in satisfaction (R2 = 0.015, F(1,195) = 3.95, p < 0.05). Similarly, satisfaction was significantly and negatively related to the dimension of administrative support, which explained 6% of the variation in satisfaction (R2 = 0.058, F(1,211) = 14.154, p < 0.001). Finally, the dimension of academic facilitation explained only 2.6% of the variation in satisfaction (R2 = 0.026, F(1,204) = 6.46, p < 0.005). The relationship was negative and significant.

These findings show that the doctoral students’ satisfaction was statistically significant and negatively related with the four dimension of service quality (i.e., supervision support, infrastructure, administrative support, and academic facilitation).

Similar findings (i.e., statistically significant negative relationships between service quality dimensions and satisfaction), were recorded by Napitupulu, et al. (2018), Sibai et al. (2021), and Wael (2015). Similarly, Datt and Singh (2021) showed that students were dissatisfied with most of the e-services on offer. Conversely, however, Kara et al. (2016), Secreto and Pamulaklakin (2015), and Ngaaso and Abbam (2016) found statistically significant positive relationships between service quality dimensions and satisfaction.

By contrast, we found that corporate image and satisfaction were significantly and positively related (R2 = 0.552, F(1,217) = 269.34, p < 0.001). This dimension accounted for the highest variation in satisfaction, at 55%. The two variables were strongly related, and one can conclude that the doctoral students were satisfied by the corporate image of the ODeL university. This result was in line with Khalil et al. (2018) and Ntabathia (2013).

As shown above, the relationships between satisfaction and all the five dimensions of service quality were statistically significant. However, the magnitude of relationship with the four dimensions with negative relationships was too small to make meaningful conclusions from the findings without further measuring the weight of the dimensions’ contributions to satisfaction.

We sought to identify whether any dimensions made greater contributions to explaining the students’ satisfaction. This procedure was deemed helpful in focusing on issues that need improvement to guarantee students’ satisfaction in the provision of student support services. Accordingly, stepwise regression was run, and the findings showed that two dimensions, namely supervision support and corporate image, stood out. Together, these dimensions explained 60% of the variance in satisfaction (R2 = 0.599, F(2,145) = 110.684, p < 0.001) as shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3

Explanatory Dimensions

| Independent variable | Dependent variable: Satisfaction | ||||

| Beta | t value | p value | R | R2 | |

| Corporate image | 0.420 | 12.543 | 0.001 | 0.777 | 0.599 |

| Supervision support | -0.041 | -3.233 | 0.002 | ||

These findings showed that the students’ satisfaction was positively influenced by the university’s corporate image, whereas the other dimensions were negatively related with satisfaction. Ntabathia (2013) also found that reputation was positively related with satisfaction. In addition, Khalil et al. (2018) and Sibai et al. (2021) found a negative relationship between satisfaction and responsiveness (which focuses on interaction between customers and service providers). Similarly, we found a negative relationship between satisfaction and supervision support, which included (a) acknowledging receipt of students’ submissions, (b) responding to students’ queries, (c) giving students adequate and timely information, (d) alerting students of useful materials, (e) giving guidance on research policies, and (f) encouraging students to work hard.

This study explored the level of Ethiopian doctoral ODeL students’ satisfaction with five dimensions of student support services. We concluded that four dimensions among the five—namely supervision support, infrastructure, administrative support, and academic facilitation—were negatively related with satisfaction. The dimension of corporate image had a significant and positive relationship with satisfaction. To determine the relative contribution of the five dimensions in explaining satisfaction, stepwise regression was run; corporate image and supervision support were the greatest contributing factors. These two dimensions explained 60% of the variation in the doctoral students’ satisfaction. This is a very important finding because supervision support and image/reputation are relevant to both conventional and ODeL institutions that offer doctoral degrees, hence the findings of this article give good insights internationally.

To enhance quality, we recommend that the university focuses more on the dimensions of supervision support and corporate image in order to improve doctoral students’ satisfaction. We emphasise that supervision support should entail timely responses with meaningful and constructive feedback on students’ proposals or chapters. This can have an important impact on keeping students active and energised with the ultimate effect of increasing the number of graduates. Moreover, guiding research students with important information regarding relevant literature, rules, and policies of research, as well as motivating and encouraging them would increase throughput. Improving the use of current technological media that facilitate ease of communication with the students would improve supervision support services and increase success rates. The university should also work on building its corporate image and that of ODeL in general, as this mode of delivery affords access to many, especially disadvantaged students who cannot access conventional modes of learning. ODeL’s flexibility, affordability, use of technology in enhancing access to knowledge, and eventually bringing the qualifications home should all be emphasised, especially to assist those who work while enrolled in postgraduate education.

Other studies using the SERVQUAL or similar models could be undertaken in Africa and internationally. Future studies could identify ODeL doctoral students’ levels of satisfaction and/or dissatisfaction with support services at educational institutions that employ e-learning models.

The standardized questionnaire from this study may also be adopted and modified in any way deemed important.

Dann, S. (2008). Applying services marketing principles to postgraduate supervision. Quality Assurance in Education, 16(4), 333-346. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880810906481

Datt, G., & Singh, G. (2021). Learners’ satisfaction with website performance of an open and distance learning institution: A case study. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 22(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v22i1.5097

Dzakiria, H. (2005). The role of learning support in open & distance learning: Learners’ experiences and perspectives. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 6(2), 95-109.

Farooq, M., Khalil-Ur-Rehman, F., Tijjani, A. D., Younas, W., Sajjad, S., & Zreen, A. (2019). Service quality analysis of private universities libraries in Malaysia in the era of transformative marketing. International Journal for Quality Research, 13(2), 269-284. https://doi.org/10.24874/IJQR13.02-02

Jain, R., Sinha, G., & De, S. K. (2010). Service quality in higher education: An exploratory study. Asian Journal of Marketing, 4(3), 144-154. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajm.2010.144.154

Kara, A. M., Tanui, E., & Kalai, J. M. (2016). Educational service quality and students’ satisfaction in public universities in Kenya. International Journal of Education and Social Science, 3(10), 37-48.

Khalil, A. A., Ragheb, M. A., Ragab, A. A., & Elsamadicy, A. M. (2018, September 21-22). Effect of service quality on student satisfaction on SMEs: The case of private schools in Egypt [Conference paper]. International Conference on Management and Information Systems 2018, Bangkok, Thailand. (pp. 94-103). http://www.icmis.net/icmis18/ICMIS18CD/pdf/S184-final.pdf

Ministry of Science and Higher Education. (2020a). Discussion document on quality human capital for quality higher education and national prosperity. Addis Ababa.

Ministry of Science and Higher Education. (2020b). National science policy and strategy. Addis Ababa.

Napitupulu, D., Rahim, R., Abdullah, D., Setiawan, M. I., Abdillah, L.A., Ahmar, A. S., Simarmata, J., Hidayat, R., Nurdiyanto, H., & Pranolo, A. (2018). Analysis of student satisfaction toward quality of service facility. Journal of Physics Conference Series, Indonesia, 954(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/954/1/012019

Ngaaso, C. K., & Abbam, A. (2016). An appraisal of students’ level of satisfaction of support services of distance education at the University of Education, Winneba. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 6(10), 168-173.

Ntabathia, M. (2013). Service quality and student satisfaction of students in private universities in Nairobi County [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Nairobi.

Nyenya, T., & Bukaliya, R. (2015). Comparing students’ expectations with the students’ perceptions of service quality provided in open and distance learning institutions in Zimbabwe’s Mashonaland East Region. International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies, 2(4), 45-53.

O’Shea, S. E., Stone, C., & Delahunty, J. (2015). “I ‘feel’ like I am at university even though I am online.” Exploring how students narrate their engagement with higher education institutions in an online learning environment. Distance Education, 36(1), 41-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2015.1019970

Paposa, K. K., & Paposa, S. S. (2022). From brick to click classrooms: A paradigm shift during the pandemic—Identifying factors influencing service quality and learners’ satisfaction in click classrooms. Management and Labour Studies, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X211066234

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298504900403

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12-40.

Secreto, P. V., & Pamulaklakin, R. L. (2015). Learners’ satisfaction level with online student portal as a support system in an open and distance e-learning environment (ODeL). Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education-TOJDE, 16(3), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.32741

Sembiring, M. G. (2015). Student satisfaction and persistence: Imperative features for retention in open and distance learning. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 10(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-10-01-2015-B002

Sibai, M. T., Bay, B., & Rosa, R. D. (2021) Service quality and student satisfaction using ServQual model: A study of a private medical college in Saudi Arabia. International Education Studies, 14(6), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v14n6p51

Sisay, S. (2020, January 4). Ministry seeks excellence with plan to classify public universities Ethiopian Monitor. https://ethiopianmonitor.com/2020/01/04/ministry-seeks-excellence-with-plan-to-classify-public-universities/

Southard, S., & Mooney, M. (2015). A comparative analysis of distance education quality assurance standards. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 16(1), 55-68.

Teeroovengadum, V., Kamalanabhan, T. J. & Seebaluck, A. K. (2016). Measuring service quality in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 24(2), 244-258. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-06-2014-0028

Tsige G. A. (2016). Ensuring the quality of doctoral student support services in open distance learning [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of South Africa.

Van Deuren, R., Tsegazeab, K., Seid, M., & Wondimu W. (2016). Ethiopian new public universities: Achievements, challenges and illustrative case studies. Quality Assurance in Education, 24(2), 158-172. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-12-2014-0054

Wael, T. (2015). Using SERVQUAL model to assess service quality and students’ satisfaction in Pavia University, Italy. International Journal of Research in Business Studies and Management, 2(3), 24-31.

Wodwossen, T. (2020, October 01). What next for a partially differentiated HE system? University World News, Issue No. 285. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200929080901365

Dear Colleague,

Thank you so much for your willingness to complete this questionnaire. The questionnaire involves two types of expected responses. First, please indicate your expectations of the student support services that should be provided. Second, respond regarding your actual experiences of the student support services provided to you since you enrolled. Kindly respond frankly and accurately.

Please record your responses regarding student support services in columns A and B.

Indicate your expectations in column A and your actual experiences in column B.

Respond using the following scale: 0 = None, 1 = Little, 2 = Some, 3 = Much, and 4 = Very Much

Please highlight/underline/encircle the one response that best describes your views in both columns A and B.

| Service | A To what extent do you feel that supervisors should provide this type of service? | B In your experience, to what extent do supervisors actually provide this type of service? | ||||||||

| 1) give clear comments on students’ submissions like proposals or chapters | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 2) acknowledge the receipt of students’ submissions without delay | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 3) give adequate information to students on ethical clearance procedures | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 4) alert students of useful resources related to the students’ doctoral projects | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 5) communicate with students via different technological media like e-mail, Skype, chatting, and the like | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 6) give guidance to students regarding policies and rules (e.g., plagiarism, structural requirements of the thesis) that govern doctoral studies | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 7) respond to students’ submissions within an agreed upon period of time | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 8) periodically encourage students to make the required submissions (e.g., chapters) | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 9) be fairly consistent over time in the comments they give to students unless new developments in the field dictate otherwise | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 10) provide information about research fund possibilities | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 11) ensure that the library is rich in e-journal and e-book collections | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 12) ensure that the online library is accessible seven days a week throughout the year | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 13) make myLife e-mail account user-friendly | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 14) ensure that ICT resources are up-to-date | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 15) provide technical assistance when students face ICT-related problems | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 16) ensure that library possesses a wide range of subject-related materials | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 17) ensure that library is equipped with recent research books | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 18) make computer labs accessible to students | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 19) Centre be in a location accessible to students | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 20) provide information on doctoral applications in both hard copy and digital (online) format | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 21) provide a response regarding admission decisions on first applications within a reasonable period | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 22) ensure that registration and re-registration processes are user-friendly | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 23) ensure that decisions of departmental higher degrees committees on doctoral students’ proposals are communicated to students as quickly as possible | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 24) provide information about administrative procedures involving doctoral students (e.g., intention to submit, library procedures) | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 25) provide training to students on how to develop a doctoral proposal | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 26) make sure doctoral workshops/seminars/training address issues are relevant to the research projects students are involved in | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 27) provide training programs in the form of seminars/colloquia for students who have progressed beyond the proposal phase | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 28) provide training on data analysis software packages (e.g., SPSS, Atlas-ti) | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 29) the university is a leading open distance e-learning university | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 30) graduates of this university have a favourable image in Ethiopia | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 31) university grants doctoral degrees that are of international standard | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 32) Ethiopians who have graduated from this university are proud of their qualifications | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 33) I recommend this university to friends/relatives/family members | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| 34) overall, I am satisfied with the services rendered by the university | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much | 0 None | 1 Little | 2 Some | 3 Much | 4 Very Much |

| Questionnaire Items | Support service component | ||||

| Supervision support | Infrastructure | Administrative support | Academic facilitation | Corporate image | |

| Clear comments from supervisors | 0.751 | ||||

| Supervisors acknowledge receipt of students’ submissions | 0.738 | ||||

| Information on ethical clearance procedures | 0.642 | ||||

| Alerting students on useful resources | 0.702 | ||||

| Using different technological media for communication | 0.715 | ||||

| Guidance on governing rules and policies | 0.732 | ||||

| Supervisors’ timely responses to students’ submissions | 0.759 | ||||

| Supervisors periodically encourage their students | 0.738 | ||||

| Supervisors’ comments consistent over time | 0.727 | ||||

| Supervisors give information on research fund possibilities | 0.726 | ||||

| α = 0.90 | |||||

| Library contains e-book and e-journal collections | 0.661 | ||||

| Online library accessible throughout the year | 0.705 | ||||

| ICT resources up-to-date | 0.664 | ||||

| Assistance for ICT-related challenges | 0.612 | ||||

| Centre library stocking subject-relating materials | 0.708 | ||||

| Centre library stocks recent research books | 0.649 | ||||

| Accessibility of computer labs | 0.597 | ||||

| Accessibility of location | 0.484 | ||||

| α = 0.84 | |||||

| User-friendliness of myLife e-mail | 0.475 | ||||

| Provision of information on doctoral application | 0.671 | ||||

| Responses on admission decisions | 0.713 | ||||

| User-friendliness of registration and re-registration | 0.769 | ||||

| Time span in communicating HDC decisions on proposal | 0.547 | ||||

| Provision of information on administrative procedures | 0.551 | ||||

| α = 0.78 | |||||

| Doctoral proposal development training | 0.664 | ||||

| Relevance of training to students’ research | 0.735 | ||||

| Provision of programs for post-proposal students | 0.711 | ||||

| Training on data analysis software | 0.648 | ||||

| α = 0.76 | |||||

| University is a leading ODL university | 0.781 | ||||

| Public image of graduates | 0.819 | ||||

| Degree meets international standard | 0.761 | ||||

| Graduates have pride in their qualifications | 0.816 | ||||

| α = 0.83 | |||||

Open Distance and e-Learning: Ethiopian Doctoral Students' Satisfaction with Support Services by Tsige GebreMeskel Aberra and Mogamat Noor Davids is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.