International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning

Volume 21, Number 2

April - 2020

An Empirical Study on Service Recovery Satisfaction in an Open and Distance Learning Higher Education Institution in Malaysia

Mohd Rushidi bin Mohd Amin1, Shishi Kumar Piaralal1, Yon Rosli bin Daud1, and Baderisang bin Mohamed2

1Open University Malaysia, 2Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia

Abstract

This study investigated the relationships among justice dimensions (distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational), university image, service recovery satisfaction, and customer behavioural outcomes (trust, word of mouth, repurchase intention, and loyalty). This study adopted a cross-sectional survey approach and data were collected through a survey of 303 students of Open University Malaysia in Malaysia who experienced service failure and service recovery. The framework was tested via partial least square structural equation modelling, and the results revealed a significant relationship between justice dimensions and service recovery satisfaction in terms of procedural and interpersonal justice. Service recovery satisfaction had a significant effect on all customer behavioural outcomes investigated. University image did not have a moderating effect on the relationship between justice dimensions and service recovery satisfaction. Theoretical and practical implications of the study are discussed in this paper.

Keywords: justice dimensions, service recovery satisfaction, university image, behavioural outcomes, open and distance learning

Introduction

The business landscape in the education sector has become more complicated due to the offering of similar academic programmes by many higher education institutions. With a large number of universities and colleges operating in Malaysia, one would expect stiff competition ahead in the higher education industry in this country (Çakıroğlu, Kokoç, Gökoğlu, Öztürk, & Erdoğdu, 2019). However, higher education institutions often neglect to recover their students’ satisfaction right after the occurrence of service failure, and scarce information is available about the determinants of service recovery satisfaction and its outcomes. An unsuccessful service recovery effort may cause the customer to leave, leading to potential adverse effects on the service provider’s financial bottom line (Tamta & Rao, 2017). Research on service failure and recovery is still progressing, and more research is required in the area of service failure to facilitate the provision of satisfactory recovery and to transform students’ dissatisfaction into satisfaction (Phuong, 2018). There is a lack of research on service recovery in Malaysia’s private higher education institutions, specifically open and distance learning (ODL) institutions. This study was carried out in the context of such institutions in order to offer useful information about the justice dimensions, service recovery satisfaction, and its outcomes.

Significance of the Study

This study contributed to the further understanding of the role of service recovery particularly in the context of ODL in Malaysia. Institutions should adopt recovery strategies that will improve their relationship with students, and further increase students’ overall satisfaction (Chahal & Devi, 2015). Therefore, service failure must be overcome and the institution must have an effective service recovery strategy in place. Service recovery through various justice dimensions is one of the potential solutions that can reinstate the level of satisfaction after the customer has experienced service failure (Smith & Mpinganjira, 2015). Implementing service recovery is one of the fundamental requirements for maintaining overall customer satisfaction and will create positive customer outcomes which can minimise customer defection (Knox & van Oest, 2014). This study will help the institution better understand the essentials of providing service right the first time, and how to deal with challenges positively if service failure does happen.

Literature Review

The leading theoretical perspective in service recovery studies has centred on justice theory (Maxham III & Netemeyer, 2002a). They explained that justice is the most suitable concept for understanding the determinants and outcomes of service recovery satisfaction. Justice theory states that in an exchange, customers evaluate a service recovery attempt as just or unjust (Bajaj & Krishnan, 2016). For researchers in service failure and recovery, justice theory is the main framework for investigating service recovery strategies and clearly understanding what constitutes a successful service recovery (McColl-Kennedy & Sparks, 2003). Thus, justice theory seems appropriate in explaining the customers’ attitude and behaviour in response to service recovery (Juhari, Awais Bhatti, & Kumar Piaralal, 2016).

Research Model

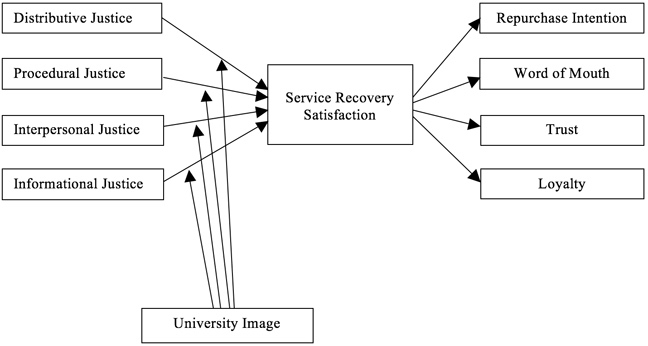

Figure 1. Theoretical framework. Adapted from “Relationships of Perceived Justice to Service Recovery, Service Failure Attributions, Recovery Satisfaction, and Loyalty in the Context of Airline Travelers,” by D. Nikbin, M. Marimuthu, S. S. Hyun, and I. Ismail, 2015, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(3), p. 243. CC BY.

The research model depicted in Figure 1 can be interpreted as made up of two parts, namely, antecedents of service recovery satisfaction that consists of distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational justice, as well as outcomes of service recovery satisfaction which consists of word of mouth, loyalty, trust, and repurchase intention. Justice theory offers theoretical support for this model. In addition, university image is included as the moderator variable, identifying the moderating effect in the relationship between the four-justice dimensions with service recovery satisfaction (Nikbin, Ismail, & Marimuthu, 2013).

Theoretical Foundation and Hypotheses Development

In this study, the four dimensions of justice were used as the determinants of service recovery satisfaction. The first dimension, distributive justice, looks at individuals’ impression of the fairness of the results they receive. In a situation of service failure, distributive justice can be defined as the fairness of the outcome of service recovery (Nikbin, Ismail, Marimuthu, & Abu-Jarad, 2011). The second dimension of justice is procedural justice. Mattila (2001) stated that procedural justice is the perception of justice in terms of processes or procedures to recover from service failure. It refers to individuals’ view of the fairness of the procedures and processes used to determine the results they received (Greenberg, 2009).

Krishna, Dangayach, and Jain (2011) and Leticia Santos‐Vijande, María Díaz‐Martín, Suárez‐Álvarez, and Belén del Río‐Lanza (2013) indicated that interactional justice should be further separated into two different dimensions, namely, interpersonal justice and informational justice. Interpersonal treatment refers to the interactional component of the service delivery process, whereas informational justice refers to the perceived adequacy and truthfulness of information explaining the causes of unfavourable outcomes (Colquitt, 2001; Greenberg, 1994). Informational justice serves to adjust responses to procedures, in that explanations provide the information needed to assess the parts of the process. Informational injustice mirrors a perceived insufficiency of fairness in a condition of sufficient information about a change (Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter, & Ng, 2001; Timming, 2012). It has been given less attention in the service marketing literature and has only lately been applied to this context (Lee & Park, 2010). This conceptualisation has not been thoroughly tested in Malaysia, particularly in the ODL context, by using the four dimensions of justice. Hence, it represents a research gap that forms the main foundation of this study. Based on the literature discussed, the hypotheses can be set out as follows:

- Hypothesis 1 (H1): Distributive justice has a significant relationship with service recovery satisfaction.

- Hypothesis 2 (H2): Procedural justice has a significant relationship with service recovery satisfaction.

- Hypothesis 3 (H3): Interpersonal justice has a significant relationship with service recovery satisfaction.

- Hypothesis 4 (H4): Informational justice has a significant relationship with service recovery satisfaction.

Customers who encounter a fair procedure, fair interpersonal treatment, and fair information dissemination regarding a process and outcome are likely to develop higher service recovery satisfaction towards the service provider. Also, customers who are treated fairly are likely to develop higher behavioural outcomes in the future (Kumar Piaralal, Kumar Piaralal, & Awais Bhatti, 2014).

Repurchase intention is one of the key outcomes of service recovery satisfaction (Thomas, Blattberg, & Fox, 2004). It refers to an individual’s decision to purchase a product or service from the same organisation again while considering their present positions (Sabharwal, Soch, & Kaur, 2010). Past researchers have found a significant relationship between service recovery and repurchase intention (Goodwin & Ross, 1992; Kelley, Hoffman, & Davis, 1993). Referral in the form of word of mouth has been identified as one of the fundamental approaches to spreading information about a product or service, either positively or negatively. Past studies demonstrated a positive relationship between service recovery satisfaction and word of mouth (WOM; Wen & Chi, 2013). Customers who receive effective service recovery will probably patronise the service provider and even spread positive WOM about the service provider, and subsequently disseminate goodwill.

Crosby, Evans, and Cowles (1990) characterised trust as a conviction created by a customer in light of the belief that the service provider is dependable and would act in the best interest of the customer. When effective service is delivered, customer satisfaction and loyalty are gained through trust, which can eliminate or minimise uncertainties and risks (Wang & Chang, 2013). An effective service recovery will likely lead to redeveloped trust because customers then believe that the service provider is honest in solving their problems.

Customer loyalty refers to customers’ commitment to a service provider, demonstrated through customers’ continued patronage with the same provider (Mahalakshmi & Karthikeyan, 2018). The application of relationship marketing in cultivating customer loyalty is gaining interest among organisations; including customers in service recovery efforts may trigger customers’ perception of recovery satisfaction and enhance their behavioural outcomes such as inducing loyalty (Bandyopadhyay, 2018). Therefore, based on the literature discussed, this study proposed the following hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 5 (H5): Service recovery satisfaction has a significant relationship with repurchase intention.

- Hypothesis 6 (H6): Service recovery satisfaction has a significant relationship with WOM.

- Hypothesis 7 (H7): Service recovery satisfaction has a significant relationship with trust.

- Hypothesis 8 (H8): Service recovery satisfaction has a significant relationship with loyalty.

The topic of university image has attracted the interest of researchers, and it is important to see how universities are creating value and developing research on their image (Osman, Saputra, & Luis, 2018). This issue is receiving increased attention because of growing competition among universities, as well as the importance and contribution of university image in attracting and recruiting students (Aghaz, Hashemi, & Sharifi Atashgah, 2015). This research enhances the existing literature in ODL and service recovery by proposing a relationship between both of these constructs but also by suggesting a moderating role for university image. Given the high level of interest in this relationship, this investigation will constitute one of the research contributions in this area. Therefore, it is posited that:

- Hypothesis 9 (H9): The relationship between distributive justice and service recovery satisfaction will be stronger when the interaction effect of university image is significant.

- Hypothesis 10 (H10): The relationship between procedural justice and service recovery satisfaction will be stronger when the interaction effect of university image is significant.

- Hypothesis 11 (H11): The relationship between interpersonal justice and service recovery satisfaction will be stronger when the interaction effect of university image is significant.

- Hypothesis 12 (H12): The relationship between informational justice and service recovery satisfaction will be stronger when the interaction effect of university image is significant.

Methodology

This study adopted a cross-sectional survey approach. The unit of analysis was the students who experienced service failure and service recovery. The Power Analysis - G*Power program was used to calculate the minimum sample size of this study (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2017). In this study, the researcher was interested in learning about students’ service recovery satisfaction, in which the students must have experienced both service failure and service recovery as provided by the institution. The university classified the information of those students who experienced service failure as private and confidential, and due to the sensitivity of the data that contained confidential information about the institution, the university was unwilling to disclose it. Due to the unavailability of the list of ODL students who experienced service failure, a purposive sampling method was adopted. Under the circumstances, random sampling was almost impossible to conduct. In this study, the data was collected through self-administered questionnaires and carried out at five OUM learning centre in Klang Valley which have been identified to have a high number of students that experienced service failure and service recovery compared to other learning centre throughout the country.

A pilot study involving 39 Open University Malaysia (OUM) students tested the instrument before conducting the main survey. Items addressing justice dimensions, service recovery satisfaction, university image, trust, repurchase intention, word of mouth, and a loyalty construct were adopted from previous studies (Andreassen, 2001; Brown, Cowles, & Tuten, 1996; Cengiz, Er, & Kurtaran, 2007; del Río-Lanza, Vázquez-Casielles, & Díaz-Martín, 2009; Kau & Loh, 2006; Maxham III & Netemeyer, 2002b; Richard & Zhang, 2012). The questionnaire was further evaluated by a group of experts comprising two academicians and a practitioner. In addition, a focus group discussion was conducted with 10 OUM students to discuss the context of the study, to ensure the questions were well understood, and to gather suggestions and comments from the respondents. Data was collected through self-administered questionnaires and carried out at OUM Learning Centre in Klang Valley. The data collection was conducted early in the January 2017 semester and spanned approximately six months. The researcher was given a timetable and dates because the seniors and newly enrolled students were having different class on different dates. The intended respondents were not newly enrolled students but rather senior students who had completed at least one semester. Therefore, the researcher only conducted the data collection on the dates when the senior students is having their classes.

Results

Data Screening

All the returned questionnaires were checked, coded, recoded, and recorded using SPSS statistical software version 23. Out of the 750 questionnaires distributed, 450 were returned. Out of 450 returned questionnaires, 90 were not usable because more than 25% of the items were unanswered, resulting in a sample of 360 questionnaires (48% response rate). The response rate is adequate and justified, as service failure and service recovery are exceptional phenomena and the response rate obtained is common in service recovery studies (Nikbin, Marimuthu, Hyun, & Ismail, 2015). Since this study was only interested in respondents that experience service failure and service recovery, 22 samples out of 360 were identified as not fulfilling this criterion. Based on inspection of the box plots of each variable, 35 cases were considered as outliers. After deleting the outliers, the previous sample of 338 respondents was reduced to 303 respondents for further analysis as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic Profile of Respondents

| Demographic profile | n | % |

| Country |

| Malaysia | 303 | 100.0 |

| Gender |

| Male | 105 | 34.7 |

| Female | 198 | 65.3 |

| Age |

| 24 years old and below | 37 | 12.2 |

| 25-29 years old | 84 | 27.7 |

| 30-34 years old | 74 | 24.4 |

| 35-39 years old | 44 | 14.5 |

| 40-44 years old | 43 | 14.2 |

| 45-49 years old | 10 | 3.3 |

| 50-54 years old | 6 | 2.0 |

| 55-59 years old | 4 | 1.3 |

| 60 years old and above | 1 | .3 |

| Education level |

| Diploma | 55 | 18.2 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 199 | 65.7 |

| Master’s degree | 39 | 12.9 |

| PhD/Doctorate | 10 | 3.3 |

| Programme |

| Accounting | 2 | .7 |

| Business Administration | 27 | 8.9 |

| Information Technology | 11 | 3.6 |

| Management | 33 | 10.9 |

| Human Resource Management | 31 | 10.2 |

| Occupational Safety and Health Management | 33 | 10.9 |

| Nursing | 36 | 11.9 |

| Islamic Studies | 13 | 4.3 |

| Early Childhood Education | 48 | 15.8 |

| Communication | 3 | 1.0 |

| TESL | 7 | 2.3 |

| Others | 59 | 19.5 |

| Year of Study |

| Year 1 | 88 | 29.0 |

| Year 2 | 86 | 28.4 |

| Year 3 | 52 | 17.2 |

| Year 4 | 47 | 15.5 |

| Year 5 | 19 | 6.3 |

| Year 6 | 6 | 2.0 |

| Year 7 | 2 | .7 |

| Year 8 | 3 | 1.0 |

This study followed the treatment recommended by Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Lee, and Padsakoff (2003) for minimising common method bias (CMB) effects. The respondents were aware that there were no correct or incorrect responses to the items in the questionnaire. As well, they were assured that their responses would be kept confidential throughout the inquiry procedure. The scale items were improved to reduce CMB by avoiding vague concepts in the questionnaire, and when such concepts were used, simpler terms were offered. To further improve the scale items and content validity, all the questions in the survey were written in an easy, precise, and simple language. Harman’s one-factor test, one of the most widely used techniques to address the issue of common method variance, was performed to examine the presence of CMB (Podsakoff et al., 2003); the variance should be less than 50%. In this study, no single factor accounted for most of the variance. Therefore, it can be concluded that CMB was not a major concern in this study.

Assessment of the Measurement Model

According to Hair, Black, Babin, and Anderson (2010), convergent validity can be assessed using factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR). According to Hair et al. (2010), factor loading should be at least 0.5. Table 2 shows that the loading values were satisfactory with a range of 0.71 to 0.92. Internal consistency refers to the extent that indicators measure the same construct consistently. The Cronbach’s alpha values in this study were in the range of 0.79 to 0.90 while the CR values were 0.88 to 0.93, indicating satisfactory convergent validity. The AVE should be at least 0.5 to establish convergent validity. The AVE values in this study were in the range of 0.66 to 0.82, indicating an acceptable level of convergent validity.

Table 2

Convergent Validity

| Factors and items | Loadings | CAa | CRb | AVEc |

| Distributional justice | | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.66 |

| DJ1 | 0.87 | | | |

| DJ2 | 0.79 | | | |

| DJ3 | 0.71 | | | |

| DJ4 | 0.87 | | | |

| Informational justice | | 0.84 | 0.9 | 0.75 |

| INFO_JU19 | 0.85 | | | |

| INFO_JU20 | 0.86 | | | |

| INFO_JU22 | 0.89 | | | |

| Interpersonal justice | | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.82 |

| INTER_JU10 | 0.9 | | | |

| INTER_JU11 | 0.92 | | | |

| INTER_JU13 | 0.91 | | | |

| Procedural Justice | | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.78 |

| PJ6 | 0.86 | | | |

| PJ7 | 0.84 | | | |

| PJ8 | 0.95 | | | |

| Service recovery satisfaction | | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.67 |

| SRS5 | 0.89 | | | |

| SRS6 | 0.83 | | | |

| SRS7 | 0.72 | | | |

| SRS8 | 0.84 | | | |

| SRS9 | 0.8 | | | |

| University image | | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.82 |

| UI1 | 0.91 | | | |

| UI2 | 0.91 | | | |

| UI3 | 0.90 | | | |

| Trust | | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.70 |

| B12 | 0.84 | | | |

| B13 | 0.78 | | | |

| B14 | 0.89 | | | |

| Word of mouth | | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.68 |

| WOM15 | 0.91 | | | |

| WOM16 | 0.87 | | | |

| WOM17 | 0.78 | | | |

| WOM18 | 0.72 | | | |

| Repurchase intention | | 0.9 | 0.93 | 0.72 |

| RI19 | 0.91 | | | |

| RI20 | 0.9 | | | |

| RI21 | 0.86 | | | |

| RI22 | 0.91 | | | |

| RI23 | 0.87 | | | |

| Loyalty | | 0.9 | 0.93 | 0.77 |

| LOYALTY24 | 0.93 | | | |

| LOYALTY25 | 0.89 | | | |

| LOYALTY26 | 0.83 | | | |

| LOYALTY27 | 0.87 | | | |

Note. a Cronbach’s alpha (CA); b Composite reliability (CR); c Average variance extracted (AVE).

Discriminant validity refers to the extent to which a particular construct differs from other constructs in the study (Garver & Mentzer, 1999). In this study, discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell and Larcker (1981) procedure, by examining whether the items loaded high on their own construct and loaded low on other constructs in the model as shown in Table 3. Table 3 also shows that all the square root of AVE values were greater than the corresponding correlation estimates. Cross-loading is the second criterion used to assess discriminant validity. To show satisfactory discriminant validity, the loading of each measurement item on its corresponding construct should be higher than its loading on other constructs (Chin, 1998). From Table 4, it can be seen that the factor loading of each indicator is greater than all of its cross-loadings.

Table 3

Discriminant Validity

| Factors | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | X7 | X8 | X9 | X10 |

| Distributive justice (X1) | 0.81 | | | | | | | | | |

| Informational justice (X2) | 0.59 | 0.87 | | | | | | | | |

| Interpersonal justice (X3) | 0.57 | 0.74 | 0.91 | | | | | | | |

| Loyalty (X4) | 0.27 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.88 | | | | | | |

| Procedural justice (X5) | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.89 | | | | | |

| Repurchase intention (X6) | 0.30 | 0.52 | 0.6 | 0.81 | 0.44 | 0.85 | | | | |

| Service recovery satisfaction (X7) | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.5 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.82 | | | |

| Trust (X8) | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.84 | | |

| University image (X9) | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.91 | |

| Word of mouth (X10) | 0.39 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.7 | 0.66 | 0.82 |

Note. Diagonals are the square roots of AVE.

Table 4

Loadings and Cross-Loadings

| Factors | TRUST | DJ | INFO_JUS | INTER_ JUS | LOYALTY | PJ | RI | SRS | UI | WOM |

| B12 | 0.84 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.53 |

| B13 | 0.78 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.52 |

| B14 | 0.89 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.68 |

| DJ1 | 0.46 | 0.87 | 0.6 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.58 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.41 |

| DJ2 | 0.33 | 0.79 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.27 |

| DJ3 | 0.26 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.4 | 0.32 | 0.23 |

| DJ4 | 0.39 | 0.87 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.49 | 0.5 | 0.32 |

| INFO_JU19 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.85 | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.58 | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| INFO_JU20 | 0.52 | 0.5 | 0.86 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.51 |

| INFO_JU22 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.6 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.55 |

| INTER_JU10 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.7 | 0.90 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.7 | 0.65 |

| INTER_JU11 | 0.6 | 0.53 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.63 |

| INTER_JU13 | 0.59 | 0.5 | 0.64 | 0.91 | 0.52 | 0.6 | 0.53 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.56 |

| LOYALTY24 | 0.55 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.93 | 0.42 | 0.85 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.66 |

| LOYALTY25 | 0.51 | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.89 | 0.34 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.6 |

| LOYALTY26 | 0.52 | 0.19 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.74 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.59 |

| LOYALTY27 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.87 | 0.32 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.55 |

| PJ6 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.38 | 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.49 |

| PJ7 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.84 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.43 |

| PJ8 | 0.54 | 0.6 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.95 | 0.42 | 0.7 | 0.63 | 0.48 |

| RI19 | 0.5 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.4 | 0.91 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.67 |

| RI20 | 0.5 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.53 | 0.76 | 0.38 | 0.90 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.66 |

| RI21 | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.86 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.45 |

| RI22 | 0.5 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0.5 | 0.79 | 0.37 | 0.91 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.63 |

| RI23 | 0.54 | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.86 | 0.4 | 0.87 | 0.5 | 0.54 | 0.63 |

| SRS5 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.59 |

| SRS6 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.51 |

| SRS7 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.27 | 0.57 | 0.27 | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.37 |

| SRS8 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.59 | 0.6 | 0.39 | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.53 |

| SRS9 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.4 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 0.47 |

| UI1 | 0.65 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 0.63 |

| UI2 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.7 | 0.91 | 0.55 |

| UI3 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.5 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.6 |

| WOM15 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.91 |

| WOM16 | 0.57 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.87 |

| WOM17 | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.78 |

| WOM18 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.4 | 0.39 | 0.72 |

The Heterotrait-Monotrait index (HTMT) was developed to address the insensitivity of the Fornell and Larcker (1981) and cross-loading criterion. As shown in Table 5, all values of the HTMT index are less than 0.90, thereby confirming discriminant validity (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015).

Table 5

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) Index

| Construct | DJ | INFO_J | INT_J | LOYALTY | PJ | RI | SRS | TRUST | UI | WOM |

| Distributive justice (DJ) | | | | | | | | | | |

| Informational justice (INFO_J) | 0.70 | | | | | | | | | |

| Interpersonal justice (INTER_J) | 0.64 | 0.85 | | | | | | | | |

| Loyalty (LOYALTY) | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.66 | | | | | | | |

| Procedural justice (PJ) | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.46 | | | | | | |

| Repurchase intention (RI) | 0.34 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.50 | | | | | |

| Service recovery satisfaction (SRS) | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 0.87 | 0.57 | | | | |

| Trust | 0.52 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.77 | | | |

| University image (UI) | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.86 | 0.82 | | |

| Word of mouth (WOM) | 0.46 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 0.75 | |

Assessment of the Structural Model

The structural model for this study was evaluated using six steps to assess for multicollinearity issues, the significance and relevance of the structural model’s relationships, the level of R2, the effect size (f2), the predictive relevance (Q2), and the q2 effect size (Hair et al., 2017). In partial least square, the multicollinearity test was carried out using the measures of variance influence factor (VIF). The results showed that the VIF values of all constructs ranged from 2.08 to 3.52, well below the suggested threshold of 5.0, thus indicating that the variables were free from multicollinearity issues (Hair et al., 2017). In assessing the significance and relevance of the structural model, the statistical significance test in PLS was accomplished using the bootstrap technique. The bootstrap resampling procedure (5000 sub-samples) was used to generate the standard errors and t-values, which indicates that the β values (path coefficients) to be statistically significant. Table 6 shows the results of hypotheses testing.

Table 6

Hypotheses Testing

| Hypotheses | OSa | SMb | SDc | T-statisticsd | P-values | Hypotheses supported? | f2 | q2 |

| Hypothesis 1: Distributive justice has a significant relationship with service recovery satisfaction. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.910 | Not supported | 0.01 | 0.003 |

| Hypothesis 2: Procedural justice has a significant relationship with service recovery satisfaction. | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 5.04 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.17 | 0.004 |

| Hypothesis 3: Interpersonal justice has a significant relationship with service recovery satisfaction. | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 2.24 | 0.030 | Supported | 0.01 | 0.004 |

| Hypothesis 4: Informational justice has a significant relationship with service recovery satisfaction. | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.88 | 0.060 | Not supported | 0.01 | 0.004 |

| Hypothesis 5: Service recovery satisfaction has a significant relationship with repurchase intention. | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 13.49 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.37 | 0.18 |

| Hypothesis 6: Service recovery satisfaction has a significant relationship with WOM. | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 15.82 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.59 | 0.18 |

| Hypothesis 7: Service recovery satisfaction has a significant relationship with trust. | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.03 | 22.78 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.83 | 0.18 |

| Hypothesis 8: Service recovery satisfaction has a significant relationship with loyalty. | 0.5 | 0.51 | 0.04 | 12.79 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.34 | 0.18 |

| Hypothesis 9: The relationship between distributive justice and service recovery satisfaction will be stronger when the interaction effect of university image is significant. | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.55 | 0.580 | Not supported | | |

| Hypothesis 10: The relationship between procedural justice and service recovery satisfaction will be stronger when the interaction effect of university image is significant. | -0.07 | -0.07 | 0.05 | 1.23 | 0.220 | Not supported | | |

| Hypothesis 11: The relationship between interpersonal justice and service recovery satisfaction will be stronger when the interaction effect of university image is significant. | -0.06 | -0.06 | 0.05 | 1.32 | 0.190 | Not supported | | |

| Hypothesis 12: The relationship between informational justice and service recovery satisfaction will be stronger when the interaction effect of university image is significant. | -0.05 | -0.06 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.390 | Not supported | | |

Note. a OS = original sample, b SM = sample means; c SD = standard deviation; d T statistics = [t-value]^ > 1.96.

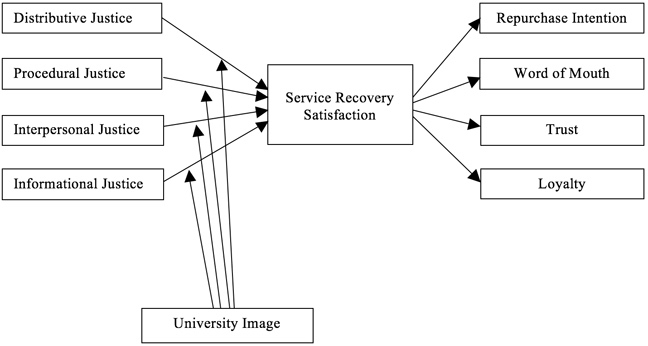

Figure 2. Full structural model with moderator.

The structural model was evaluated by running the PLS algorithm to examine the β-values of the path coefficients and R2 values as shown in Figure 2. The R2 test was performed to examine the percentage of variance in the endogenous variables that can be explained by the exogenous variables. The results indicate that the R2 values were distributed between 0.25 and 0.74. Service recovery satisfaction had the highest R2 value indicating that the exogenous variables explain 74% of the variance in service recovery satisfaction. The lowest R2 value was reported for loyalty (R2 = 0.25), indicating that 25% of the variance in loyalty was explained by the exogenous variables. The R2 values for trust (R2 = 0.45) and loyalty (R2 = 0.37) indicated that 45% of the variance in trust and 37% of the variance in loyalty were explained by the exogenous variables.

To test the moderating effect, one should test whether the interaction between independent and moderator variables have a significant effect on the dependent variable. If the interaction between the independent variable and moderator variable is significant, it can be concluded that the moderator variable has a significant effect on the dependent variable (Hair, et al., 2014). In the analysis, the PLS product-indicator approach was applied to determine the moderating effect. To test the effect, each predictor variable and university image were multiplied to create an interaction construct (i.e., distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational justice times university image) to predict service recovery satisfaction, as shown in Figure 2. The existence of moderation would be proven if the influence of the interaction variable on the criterion variable were found to be significant. Results from Table 6 show that university image does not moderate the relationship between each justice dimensions and service recovery satisfaction.

Discussion

In this study, the respondents differentiated outcomes and process by rating distributive justice as an outcome construct, with procedural, interpersonal, and informational justice as the process constructs. The empirical results of the investigation demonstrate that the hypothesised relationships of procedural justice and interpersonal justice with service recovery satisfaction are supported. Therefore, it can be deduced that the students who experienced effective service recovery are more appreciative of the process of justice. Therefore, this study has narrowed the boundary of the generalizability of past studies in terms of procedural and interpersonal justice. The results also show that the procedural and interpersonal justice of OUM will affect the level of the student service recovery satisfaction, consistent with previous studies in service recovery setting such as Pai (2015) and, Singh and Crisafulli (2016).

However, the hypothesised relationships of distributive and informational justice with service recovery satisfaction are not supported in this study. The insignificant result of distributive justice contradicts the findings of other service recovery studies such as Kim, Kim, and Kim (2009) and Waqas, Ali, and Khan (2014), but is consistent with Fu, Wu, Huang, Song, and Gong (2015) and Roschk and Gelbrich (2014) who mentioned that providing compensation to customers does not always bring desirable outcomes. The results also show that informational justice was insignificantly associated with service recovery satisfaction and inconsistent with the findings of other service recovery studies such as De Clercq and Saridakis (2015) and Taamneh (2015).

Considerable evidence from the service recovery literature indicates that service recovery satisfaction improves customer outcomes towards service providers who implement a service recovery strategy Lee (2018). In service recovery research, consumer outcome-based studies have focused on how service recovery strategy improves customer outcomes such as repurchase intention, word of mouth, trust, and loyalty. Our findings show that OUM students rated their service provider strongly and positively for all the outcomes under study, indicating that they are satisfied with the service recovery effort. The results in this study are consistent with prior service recovery studies such as Bhandari, Tsarenko, and Polonsky (2007) and Kau and Loh (2006).

The hypothesised moderating effect of university image on the relationship between justice dimensions and service recovery satisfaction is not supported. The findings of this study also contradict that of Lai, Griffin, and Babin (2009) who stated that when customers have a positive mind pattern of an image, this will lead to high satisfaction because these customers believe that the service provider will still bring benefits to them in the future; the effect of justice dimensions on service recovery satisfaction may be stronger for customers who have a positive image. Therefore, to discourage the students from switching to other institutions, OUM should continuously work to enhance customer relationship management and should make it a priority to improve their services and so portray more positive values for the customers, as suggested by Kaura (2013).

Conclusion

This study has provided insight into the factors that may strengthen relationships and enable service providers to increase both their service recovery satisfaction level and overall student retention rates. The findings of this study also confirm and highlight the influence of service recovery satisfaction on behavioural outcomes. The findings provide early empirical support to service providers in developing strategies that will encourage their customers to remain loyal to them.

The aim of this study was to investigate how the justice dimensions affect service recovery satisfaction and its outcomes, including the moderator effect of university image. The first theoretical contribution of this study deals with the relationships between justice dimensions and service recovery satisfaction and suggests that the four justice dimensions do not contribute equally to service recovery satisfaction. This means that different forms of recovery strategies have different effects on customer recovery satisfaction. The second theoretical contribution of this study deals with the relationship between service recovery satisfaction and its outcomes. The logic for this relationship stems from the fact that customer satisfaction is important for a business-oriented organisation because it is the main factor of customer retention and company market share (Hansemark & Albinsson, 2004). Barsky and Nash (2003) theorised that satisfaction improves profitability by expanding the business through gaining market share and increasing profit margins. Therefore, this study highlighted the importance of service recovery satisfaction in developing favourable and positive customer outcomes for the institution. The third theoretical contribution of this study is the moderating effect of the university image. Although the empirical results of this study revealed that the university image does not have a moderating effect, this study suggests that the reason why service recovery satisfaction cannot be explained by justice dimensions or university image alone is that it requires other determinants, especially in the service failure and recovery context.

The practical implications for long-term financial performance in the context of ODL in Malaysia are that developing and maintaining a good customer base is viewed as one of the most important drivers in the customer life cycle or lifetime value (Ferrentino, Cuomo, & Boniello, 2016). These findings suggest that institutions focus on improving customer service recovery satisfaction. The results from this study provide new insights about the current relationship of the customer and service provider which are undeniably important and valuable for service providers seeking to improve their profitability and maintain competitiveness in the marketplace (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016).

References

Aghaz, A., Hashemi, A., & Sharifi Atashgah, M. S. (2015). Factors contributing to university image: The postgraduate students’ points of view. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(1), 104-126. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2015.1031314

Andreassen, T. W. (2001). From disgust to delight: Do customers hold a grudge? Journal of Service Research, 4(1), 39-49. doi: 10.1177/109467050141004

Bajaj, H., & Krishnan, V. R. (2016). Role of justice perceptions and social exchange in enhancing employee happiness. International Journal of Business Excellence, 9(2), 192-209. doi: 10.1504/IJBEX.2016.074843

Bandyopadhyay, N. (2018). Whether service quality determinants and customer satisfaction influence loyalty: A study of fitness services. International Journal of Business Excellence, 15(4), 520-535. doi: 10.1504/IJBEX.2018.093875

Barsky, J., & Nash, L. (2003). Customer satisfaction: Applying concepts to industry-wide measures. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 44(5/6), 173-183. doi: 10.1016/S0010-8804(03)90122-4

Bhandari, M. S., Tsarenko, Y., & Polonsky, M. J. (2007). A proposed multi-dimensional approach to evaluating service recovery. Journal of Services Marketing, 21(3), 174-185. doi: 10.1108/08876040710746534

Brown, S. W., Cowles, D. L., & Tuten, T. L. (1996). Service recovery: Its value and limitations as a retail strategy. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 7(5), 32-46. doi: 10.1108/09564239610149948

Çakıroğlu, Ü., Kokoç, M., Gökoğlu, S., Öztürk, M., & Erdoğdu, F. (2019). An analysis of the journey of open and distance education: Major concepts and cutoff points in research trends. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20(1), 1-20. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v20i1.3743

Cengiz, E., Er, B., & Kurtaran, A. (2007). The effects of failure recovery strategies on customer behaviours via complainants perceptions of justice dimensions in banks. Banks and Bank Systems, 2(3), 174-188. Retrieved from https://businessperspectives.org/author/ekrem-cengiz

Chahal, H., & Devi, P. (2015). Consumer attitude towards service failure and recovery in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 23(1), 67-85. doi: 10.1108/QAE-07-2013-0029

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295-336). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386-400. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.386

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millenium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425-445. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.425

Crosby, L. A., Evans, K. R., & Cowles, D. (1990). Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. Journal of Marketing, 54(3), 68-81. doi: 10.2307/1251817

De Clercq, D., & Saridakis, G. (2015). Informational injustice with respect to change and negative workplace emotions: The mitigating roles of structural and relational organizational features. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 2(4), 346-369. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-09-2015-0033

del Río-Lanza, A. B., Vázquez-Casielles, R., & Díaz-Martín, A. M. (2009). Satisfaction with service recovery: Perceived justice and emotional responses. Journal of Business Research, 62(8), 775-781. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.09.015

Ferrentino, R., Cuomo, M. T., & Boniello, C. (2016). On the customer lifetime value: A mathematical perspective. Computational Management Science, 13(4), 521-539. doi: 10.1007/s10287-016-0266-1

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50. doi: 10.2307/3151312

Fu, H., Wu, D. C., Huang, S. S., Song, H., & Gong, J. (2015). Monetary or nonmonetary compensation for service failure? A study of customer preferences under various loci of causality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 46, 55-64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.01.006

Garver, M., & Mentzer, J. (1999). Logistics research methods: Employing structural equation modelling to test for construct validity. Journal of Business Logistics, 20(1), 33-57. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/openview/a778d630df6747e2918f1527a34cbd76/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=36584

Goodwin, C., & Ross, I. (1992). Consumer responses to service failures: Influence of procedural and interactional fairness perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 25(2), 149-163. doi: 10.1016/0148-2963(92)90014-3

Greenberg, J. (1994). Using socially fair treatment to promote acceptance of a work site smoking ban. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(2), 288-297. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.79.2.288

Greenberg, J. (2009). Promote procedural and interactional justice to enhance individual and organizational outcomes (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781119206422.ch14

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Hansemark, O. C., & Albinsson, M. (2004). Customer satisfaction and retention: The experiences of individual employees. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 14(1), 40-57. doi: 10.1108/09604520410513668

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Juhari, A. S., Awais Bhatti, M., & Kumar Piaralal, S. (2016). Service quality and customer loyalty in Malaysian Islamic insurance sector exploring the mediating effects of customer satisfaction. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 6(3), 17-36. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v6-i3/2030

Kau, A., & Loh, W. Y. E. (2006). The effects of service recovery on consumer satisfaction: A comparison between complainants and non‐complainants. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(2), 101-111. doi: 10.1108/08876040610657039

Kaura, V. (2013). Service convenience, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty: Study of Indian commercial banks. Journal of Global Marketing, 26(1), 18-27. doi: 10.1080/08911762.2013.779405

Kelley, S. W., Hoffman, K. D., & Davis, M. A. (1993). A typology of retail failures and recoveries. Journal of Retailing, 69(4), 429-452. doi: 10.1016/0022-4359(93)90016-C

Kim, T., Kim, W. G., & Kim, H.-B. (2009). The effects of perceived justice on recovery satisfaction, trust, word-of-mouth, and revisit intention in upscale hotels. Tourism Management, 30(1), 51-62. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.04.003

Knox, G., & van Oest, R. (2014). Customer complaints and recovery effectiveness: A customer base approach. Journal of Marketing, 78(5), 42-57. doi: 10.1509/jm.12.0317

Krishna, A., Dangayach, G. S., & Jain, R. (2011). Service recovery: Literature review and research issues. Journal of Service Science Research, 3(1), 71-121. doi: 10.1007/s12927-011-0004-8

Kumar Piaralal, N., Kumar Piaralal, S., & Awais Bhatti, M. (2014). Antecedent and outcomes of satisfaction with service recovery: A study among mobile phone users in central region of Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 10(12), 210-221. doi: 10.5539/ass.v10n12p210

Lai, F., Griffin, M., & Babin, B. J. (2009). How quality, value, image, and satisfaction create loyalty at a Chinese telecom. Journal of Business Research, 62(10), 980-986. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.10.015

Lee, E. J., & Park, J. (2010). Service failures in online double deviation scenarios: Justice theory approach. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 20(1), 46-69. doi: 10.1108/09604521011011621

Lee, S. H. (2018). Guest preferences for service recovery procedures: Conjoint analysis. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 1(3), 276-288. doi: 10.1108/JHTI-01-2018-0008

Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80, 69-96. doi: 10.1509/jm.15.0420

Leticia Santos‐Vijande, M., María Díaz‐Martín, A., Suárez‐Álvarez, L., & Belén del Río‐Lanza, A. (2013). An integrated service recovery system (ISRS): Influence on knowledge‐intensive business services performance. European Journal of Marketing, 47(5/6), 934-963. doi: 10.1108/03090561311306994

Mahalakshmi, V., & Karthikeyan, K. (2018). An empirical evaluation of customer satisfaction and customer loyalty towards the services rendered by both private and public sector banks in Tamil Nadu. International Journal of Business Excellence, 16(2), 233-255. doi: 10.1504/IJBEX.2018.094706

Mattila, A. S. (2001). The effectiveness of service recovery in a multi-industry setting. Journal of Services Marketing, 15(7), 583-596. doi: 10.1108/08876040110407509

Maxham, J. G., III., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002a). A longitudinal study of complaining customers’ evaluations of multiple service failures and recovery efforts. Journal of Marketing, 66(4), 57-71. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.66.4.57.18512

Maxham, J. G., III., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002b). Modeling customer perceptions of complaint handling over time: The effects of perceived justice on satisfaction and intent. Journal of Retailing, 78(4), 239-252. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(02)00100-8

McColl-Kennedy, J. R., & Sparks, B. A. (2003). Application of fairness theory to service failures and service recovery. Journal of Service Research, 5(3), 251-266. doi: 10.1177/1094670502238918

Nikbin, D., Ismail, I., & Marimuthu, M. (2013). The relationship between informational justice, recovery satisfaction, and loyalty: The moderating role of failure attributions. Service Business, 7(3), 419-435. doi: 10.1007/s11628-012-0169-3

Nikbin, D., Ismail, I., Marimuthu, M., & Abu-Jarad, I. Y. (2011). The impact of firm reputation on customers’ responses to service failure: The role of failure attributions. Business Strategy Series, 12(1), 19-29. doi: 10.1108/17515631111106849

Nikbin, D., Marimuthu, M., Hyun, S. S., & Ismail, I. (2015). Relationships of perceived justice to service recovery, service failure attributions, recovery satisfaction, and loyalty in the context of airline travelers. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(3), 239-262. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2014.889028

Osman, A., Saputra, R., & Luis, M. (2018). Exploring mediating role of institutional image through a complete structural equation modeling (SEM): A perspective of higher education. International Journal for Quality Research, 12(2), 517-536. doi: 10.18421/IJQR12.02-13

Pai, F. (2015). The effects of perceived justice and experience on service recovery satisfaction and post-purchase behaviours in the airline industry. International Journal of Services and Operations Management, 21(2), 175-186. doi: 10.1504/IJSOM.2015.069378

Phuong, T. H. (2018). Perceived justice in performance appraisal among Vietnamese employees: Antecedents and consequences. International Journal of Business Excellence, 15(2), 209-221. doi: 10.1504/IJBEX.2018.091920

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Padsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Richard, J. E., & Zhang, A. (2012). Corporate image, loyalty, and commitment in the consumer travel industry. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(5/6), 568-593. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2010.549195

Roschk, H., & Gelbrich, K. (2014). Identifying appropriate compensation types for service failures: A meta-analytic and experimental analysis. Journal of Service Research, 17(2), 195-211. doi: 10.1177/1094670513507486

Sabharwal, N., Soch, H., & Kaur, H. (2010). Are we satisfied with incompetent services? A scale development approach for service. Journal of Services Management, 10(1), 125-142. Retrieved from https://web.a.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=rnl%3d09724702%26AN%3d50746193

Singh, J., & Crisafulli, B. (2016). Managing online service recovery: Procedures, justice and customer satisfaction. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 26(6), 1-37. doi: 10.1108/JSTP-01-2015-0013

Smith, A., & Mpinganjira, M. (2015). The role of perceived justice in service recovery on banking customers’ satisfaction and behavioral intentions : A case of South Africa. Banks and Bank Systems, 10(2), 35-43. Retrieved from https://businessperspectives.org/author/alex-smith

Taamneh, A. (2015). The impact of practicing interactional justice on employees organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) in the Jordanian Ministry of Justice. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 6(1), 108-119. Retrieved from https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/EJBM/article/view/20954/21519

Tamta, V., & Rao, M. K. (2017). The effect of organisational justice on knowledge sharing behaviour in public sector banks in India: Mediating role of work engagement. International Journal of Business Excellence, 12(1), 1-22. doi: 10.1504/IJBEX.2017.083330

Thomas, J. S., Blattberg, R. C., & Fox, E. J. (2004). Recapturing lost customers. Journal of Marketing Research, 41(1), 31-45. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.41.1.31.25086

Timming, A. R. (2012). Tracing the effects of employee involvement and participation on trust in managers: An analysis of covariance structures. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(15), 3243-3257. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.637058

Wang, E. S. T., & Chang, S. Y. (2013). Creating positive word-of-mouth promotion through service recovery strategies. Services Marketing Quarterly, 34(2), 103-114. doi: 10.1080/15332969.2013.770661

Waqas, M., Ali, H., & Khan, M. A. (2014). An investigation of effects of justice recovery dimensions on students’ satisfaction with service recovery in higher education environment. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 11(3), 263-284. doi: 10.1007/s12208-014-0120-5

Wen, B., & Chi, C. G. (2013). Examine the cognitive and affective antecedents to service recovery satisfaction: A field study of delayed airline passengers. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(3), 306-327. doi: 10.1108/09596111311310991

An Empirical Study on Service Recovery Satisfaction in an Open and Distance Learning Higher Education Institution in Malaysia by Mohd Rushidi bin Mohd Amin, Shishi Kumar Piaralal, Yon Rosli bin Daud, and Baderisang bin Mohamed is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.