Volume 19, Number 5

Frank H. T. de Langen

Open University of the Netherlands

The definition of openness influenced the sustainability of business models of Open Education (OE). Yet, whether openness is defined as the free (re)usage of resources, or the free entry in courses, there always is a discussion on who pays for the resources used in these offerings. The free offering of courses or materials raises the question if OE can be maintained independent of large government subsidies. This article analyzes four cases that each have a different approach to OE and (financial) survival. The aim of this study is to determine the most efficient conditions for a sustainable OE business model.

Instead of using different earning models, this research concentrates on the different aspects of unbundling (costs, income, and financiers), arguing that an adjusted Business Model Canvas can be used to analyze the not-for-profit organizations in higher education institutions (HEIs). The cases are OpenupEd, FemTechNet, MERLOT, and Lumen Learning. Openness plays different roles in the business models of the different organizations. For OpenupEd and MERLOT, openness of the materials offered to students and teachers (MOOCs, OER) is essential. For FemTechNet, openness is part of the need to collaborate and share within their community. Commercial organizations, such as Lumen Learning, use free materials to teach educational organizations to use these materials for their own courses. All four organizations use different key activities and key resources (for example, management competencies, social skills, or design and teaching skills) for their continuity. Yet, despite the differences between the case-organizations, community building is important in all cases. Either because producers and users of Open Education become identical, because standardization does decrease costs and increases findability and quality, or because they can bridge the difference between supply and competences necessary for usage of Open Education.

Keywords: open education, MOOCs, DOCCs, business models, collaboration, OpenupEd, MERLOT, FemTechNet, Lumen Learning, sustainability

Higher educational institutions have offered classes, public lectures, summer schools, and alike, for free. Marshall (2012) states that "it could [be]... argued that public libraries were a form of open education with freely available content" (p. 112). It was the combination of the technical possibilities of the internet and a new social attitude towards openness that an open movement in education emerged. Open Education (OE) seems to take on two distinguished forms, Open Educational Resources (OER; UNESCO, 2002, 2012) and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs; Cormier, 2008).

MOOCs became so popular that The New York Times labelled 2012 "The Year of the MOOC" (Pappano, 2012). Hollands and Tirthali (2014) stated that due to these trends, education is changing towards education for more at lower costs and a change from knowledge accumulation towards skills and competences (p. 7). Although the authors are optimistic, they conclude that MOOCs do not lower educational costs (p. 168), or replace traditional education.

MOOCs are criticized for different reasons (Online Course Report, 2016; Czerniewicz, Deacon, Glover, & Walji, 2017). Despite all of the critique on the effectiveness of MOOCs, the production of MOOCs is still increasing. Especially in Europe, new initiatives continue to emerge (Jansen & Goes-Daniels, 2016). European initiatives are the European Multiple MOOC Aggregator (financed by the EU), Futurelearn.com, which offers a hosting site for MOOCs, and an EU-website as OpenEducationEuropa, which distributes news and tries to organize communities around several topics within OE. Slowly MOOCs are changing. Different authors (Salisbury, 2014; Burd, Smith, & Reisman, 2015; de Langen, 2008, 2011) concentrate on the possible earning model and see different possibilities to generate an income in combination with a free MOOC. Some providers ask a fee, sell packages, or request money for the assessments and certificate; others earn an income using data on students to inform potential employers about talented job seekers. Other courses are transformed into so-called small private online course (SPOCs) offering paid in-company training. Several of these developments move the free online courses into the domain of traditional online learning.

Open Educational Resources (OER) are defined as: "The open provision of educational resources... for consultation, use and adaptation by a community of users for non-commercial purposes" (UNESCO, 2002, p. 24). They are offered in different areas and with different motives. In China and Russia, the OER play a role in standardization of the quality of education, making educational materials available for remote parts of the country (Sigalov & Skuratov, 2012; Wang & Zhao, 2011). In Africa, organizations work together in OER Africa, to improve education by offering OER and stimulating others to develop more materials (http://www.oerafrica.org/about-us/who-we-are). Expectations were that OER would lower the costs of education (Wiley, Green & Soares, 2012; McGreal, Miao, & Mishra, 2016) because they could replace textbooks for students and support teachers in making their own materials. Cengage Learning (2016) interviewed several experts and OER-users. They started out with: "Clearly, OER holds promise... (for) institutions seeking to offer some financial relief... (to) teaching and learning" (p. 2); however, they concluded that the usage of OER is not simple and can be costly, depending on the amount of work necessary to integrate the materials in the curriculum.

Despite expectations, MOOCs didn't disrupt the international educational sector and OER didn't replace textbooks. Both are still developing and have not reached a stable steady state. In this research, the long term financial survival (sustainability) is analyzed, studying different models, which take a different road towards sustainability. The main purpose is to see what mechanisms can be applied so OE can fulfill its promises, in a structural way, independent of onetime subsidies and gifts. Although OE (especially OER) can be used in all levels of education, the focus of this research is on higher education.

One such mechanisms seems to be unbundling, which is discussed in the next paragraph. Paragraph three presents four cases: 1) a European MOOC-platform (OpenupEd), 2) a United States-based OER-platform (MERLOT), 3) an alternative for MOOCs (DOCCs), and 4) a commercial initiative between OER and HEIs (Lumen Learning). In the first three cases, interviews are held, while the last case is based on the canvas model as provided by the organization. The article is concluded by analyzing the similarities and differences between the case studies and drawing some conclusions on the general sustainability of Open Education systems.

Christensen, Johnson, & Horn (2010) distinguishes three kinds of business models: the solution shops (experts, research); the value-adding process businesses (transformation, teaching); and facilitated user networks (communities, communication). Typical modern-day universities have "three fundamentally different and incompatible business models all housed within the same organization" (Christensen, Horn, Caldera, & Soares, 2011, p. 35). They argue that the combination of these models will lead to transaction costs. Education could be offered at lower costs when not combined within one organization with research and communities. Unbundling the processes reduces the overhead costs. As Christensen et al. (2011) point out, this development will require a different kind of accreditation, which is seen as a barrier supporting the old structure, hindering educational innovation. This is supported by Mazoué (2014) and Kelly and Hess (2013), who both describe accreditation as a barrier to new forms of education and innovation, guarding the old structures. Sheets and Crawford (2012) support the idea of unbundled models: "Especially promising are open, multi-sided, and unbundled models that involve facilitated networks" (p. 48).

Mulder and Janssen (2013) used unbundling to develop a sustainable model for Open Education. They unbundle the different activities into three components on the supply side and two on the demand side. On the supply side they distinguish OER (freely accessible, free of pay), open learning services (freely accessible, part free and part paid, including assessments and exams), and open teaching efforts (supporting activities, generally not free). On the demand side, they distinguish a demand of learners, which should be accessible and affordable, and a demand of society, as result of employability and capabilities development; education should be open towards new and changing demands from society and the labor market. Sustainability is reached through a combination of paid activities with the supply of free resources. Central to the sustainability of this model is the notion that HEI's have skills, competences, or services to offer for which students or others are prepared to pay.

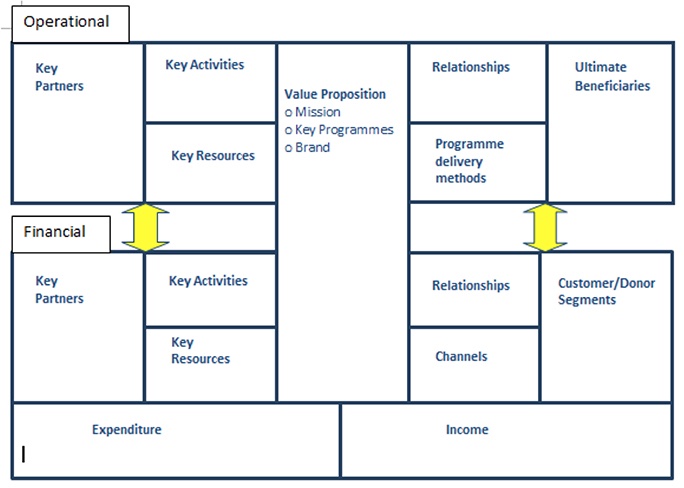

Christensen et al. (2011) did analyze educational institutes without paying attention to the special role of open education. Likewise, Mulder and Janssen (2013) studied educational institutions that offered both traditional and open education. In this study, cases are analyzed in which open education is their main activity. Sanderse (2014) studies the organizational models of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), where she extends the business model canvas of Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) into a two-layer business canvas (Figure 1). The customers of the original Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) model are replaced by stakeholders and beneficiaries. The model unbundles the financial and operational sphere. In the operational layer, all is aimed at providing services towards the beneficiaries (for example in Sanderse [2014], wildlife and patients). The second layer describes how the organizations (WWF, Médecins sans Frontières) finance their operational activities through the attraction of financial stakeholders (governments, private organizations, individuals).

Using this model to describe education, the operational level describes how teachers deliver education and educational services - as in Mulder and Janssen (2013) - towards students, financed through subsidies, gifts, grants, and alike (as described in the second layer).

In a fully OE system, education is offered for free. The financial layer describes the motives of the subsidizer, and the activities necessary to obtain and hold the required funds. In different educational systems - free, (un)bundled, or traditional - other motives will play a role and the education will take on different forms (MOOCs, OER, SPOCs).

Figure 1. Business model canvas for NGO's. Adapted from The Business Model Canvas of NGOs (p. 47), by J. Sanderse, 2014, Open Universiteit. Adapted with permission.

The major purpose of this study is to explore the success factors for sustainability in OE in four different kinds of "business" models, to see if there are similarities and/or differences between the cases. In other words, how they balance the operational and financial levels. In-depth interviews are used because of the explorative character of this study. In an earlier (unpublished) study, the questionnaires in Sanderse (2014) were used. During these interviews it became clear that the level of details was too high for the interviewees given the length of the interviews. The questionnaires were then summarized into two major categories:

As stated above, four cases were selected, based on the different ways they try to sustain diverse forms of OE. What the organizations have in common is that they don't receive structural government subsidies. At least one representative of each organization was interviewed, and a synopsis of the interview was sent to the interviewees, who then commented on, returned, and approved it. Lumen Learning was added as an additional case based on its own business model description. One of the founders, David Wiley, was asked for comments on the description of Lumen Learning and agreed with the description by mail (April 20th, 2017).The resulting interpretations are, of course, our responsibility; the case descriptions and details are provided in Table 1.

Table 1

A Summary of the Organizations Analyzed, the People Interviewed, and the Documents Retrieved

| Organization | People interviewed (type, role, and date ) | Information retrieved (Documents and websites used) |

| FemTechNet | Dr. Sharon Irish, Video-skype, 11-23-2016 Dr. Elizabeth Losh, face-to-face interview, Leiden (Netherlands), 05-19-2017 Both initiators and early participants in FemTechNet. | Website: http://FemTechNet.org/ Documents Strategic plan: http://FemTechNet.org/publications/manifesto/ DOCCs: http://FemTechNet.org/docc/ |

| Lumen Learning | Based on the business model available on: https://docs.google.com/drawings/d/1l-kSBcCCupbBGOvxZkRy3hQkcnqZuLTmeFuMmlC3zwo/edit | Website: http://lumenlearning.com/ Documents Mission statement: https://lumenlearning.com/about/mission/ |

| MERLOT | Dr. Gerry Hanley, Executive Director, MERLOT/Assistant Vice Chancellor California State University, Video-skype, 10-01-2015 | Website: http://www.MERLOT.org/ Documents Strategic plan: http://info.MERLOT.org/MERLOT help/index.htm#who_we_are.htm Website for students: http://www.MERLOT x.org/ |

| OpenupEd | Drs. Darco Janssen, face-to-face interview, Heerlen (Netherlands), 06-01-2015, coordinator OpenupEd | Website: http://www.OpenupEd.eu/ Documents Mission statement: http://www.OpenupEd.eu/95-evolution-of-OpenupEd |

FemTechNet is a network founded in 2012 by Anne Balsamo and Alexandra Juhasz consisting of feminists in academics and arts. Juhasz and Balsamo (2012) state that they built FemTechNet on long-standing feminist principles and processes as sharing power, respecting diversity, creating safe spaces for collaborating, and technologically-enabled interaction.

According to the interviews (with dr. Losh and dr. Irish, see Table 1), the initial goal of FemTechNet was twofold, (1) to work on the legacy of feminist history, art, and teaching; and (2) to use technology to develop alternatives for MOOCs, based on co-construction and two-way communication. The need for a safe environment was mentioned several times. In general, when discussing gender and sexual related subjects, the students need their privacy. This raised the question of when and how to use social media, or more private means of media, what can be shared publicly, and which should not.

FemTechNet is organized through committees, with a steering committee as the main committee. The steering committee has no members. Decisions with regard to future developments are made at the steering meetings by those who (electronically) show up at the meeting. These decisions are posted on an electronic board and if there are not objections, they become part of the program of FemTechNet. The other committees have special objectives: race and ethnic studies, operations, and pedagogy projects. The working committees produce educational materials (podcasts, modules, videos, etc.), but individuals also are sometimes engaged in social activities, with or without support of the group as a whole. Stakeholders are mostly feminist academics, teaching or doing research, who take an interest in the activities of the organization. This group has connected since its inception to other groups that tackle issues of oppression because of race, ethnicities, sexualities, or gender. An example of this is the Center for Solutions to Online Violence, and organization that helps people safely navigate digital experiences and understand the impacts of, and responses to, online violence.

Although FemTechNet participants are primarily from the U.S. network, there are also individual participants from other countries as well, including Canada. Again, such a development depends on the labor invested by (potential) new participants. One collaboration, with a community in Bangalore, India, was not fruitful due to of the distances in time and space.

Central to the operational layer are the Distributed Open Collaborative Courses (DOCCs). A DOCC is described as "an innovative experiment in the use of networked technologies that engage multiple communities and will yield important lessons for many stakeholders" (FemTechNet, 2013, p. 9). The website lists four DOCCs on Collaborations in Feminism & Technology, with the producers of the DOCCs in FemTechNet also acting as the users. In this sense, the network deviates from other platforms of learning objects and courses (i.e., MOOCs), where producers and users often are different individuals or organizations. The white paper on FemTechNet states that: "MOOC efforts often represent a step backwards, by promulgating a standardization of format rather than a focus on processes that support global access to learning and the reciprocity of teaching and learning" (FemTechNet, 2013, p. 5). Another critique on MOOCs is that universities would rather spend resources in MOOCs than on investing in real innovations in teaching and learning.

The participants in FemTechNet work together on so-called Key Learning Projects (http://FemTechNet.org/get-involved/self-directed-learners/key-learning-project/), developing learning objects that can be used in the DOCCs or in other courses. These projects are developed by teachers, but students can, and do, also contribute. Professor Irish indicated that the network also develops tools with respect to privacy and security, especially relating to feminist approaches and individual affirmations or choices that come under attack (S. Irish, personal communication, November 23, 2016). Yet, central to all these projects is what is called feminist pedagogy, "a pedagogical framework built on the analysis and exploration of visible and invisible modes of learning" (FemTechNet, 2013, p. 4). Because of the shared feminist ideology, and also the shared belief in the inadequacy of present pedagogical methods, the participants of the network decided to work together to develop the DOCC, and later to work on other emerging initiatives. An important aspect of the network are the personal relations.

Subsidies and grants are the second source of financing the network. The members of the network often work at institutions involved in gender and ethnic studies. They try to align their projects with the objectives of FemTechNet, hiring members without permanent situations to carry out some of the work. Institutes support the network by supplying licenses or help with the conferences. Others help with web hosting and server space. These contributions are important as much of the organizational efforts are done through groupware; the conferences (femtechnet.org/amc2017/) act as meeting places, which facilitates later electronic communication.

The DOCCs are part of the open educational resources offered by the network and the operational level is aimed at the participants (students, teachers, and researchers). The value offering consists of the alternative pedagogical feminist approach of materials on different subjects, related to gender, race, and sexuality, but also safety and digital participation. The key resources on the operational level are the voluntary members of the network; although working with a lot of freeware, the key resources (communication, meetings, and research facilities) are financed through the second level. As stated during the interviews: "This is a really minimal amount of money; FemTechNet hasn't been paid for research, but rather finds ways to leverage our work as research to benefit members of the collective - more use value than exchange value." (E. Losh, personal communication, May 19, 2017). The acquired competences make participants in FemTechNet, desired participants in other research and educational projects. On the other hand, the ideological value-offer attracts new participants and generates income through grants from institutions with the same public objective.

OpenupEd provides a portal, through which educational institutions can offer their MOOCs. As described on their website, OpenupEd is an open, non-profit organization that forms partnerships in an effort to "open up" education for all through the creation of MOOCs. For institutions that want to participate in OpenupEd, there are some severe restrictions. For example, they have to be an HE-institute, recognized by the national educational administration, obtain the OpenupEd quality label (the E-xcellence label), evaluate and monitor their MOOCs, and pay an annual fee of €2.500. According to the interviewee, openness is defined as the removal of barriers for learners and stimulating social inclusion (see http://www.OpenupEd.eu/mooc-features/42-openness-to-learners for the characteristics of openness).

OpenupEd has made a stakeholder analyses, with the primary stakeholders as the paying partners who use the portal. Although OpenupEd sees learners as stakeholders, they have no direct relationship with them. OpenupEd does not receive structural subsidies from national governments or the EU. Yet, the platform and its partners participate in national and international projects aimed at the (open) education policies, receiving project subsidies, so these governments and the EU are seen as important stakeholders.

Given the importance of the HEI's as stakeholders, the activities of OpenupEd are directed at providing different services as a hosting (portal function), a searchable database of MOOCs, shared marketing, quality label, and additional services. Acknowledging the importance to offer value to the stakeholders, there are plans to expand their services, offering new research (for example, in the field of learning analytics and big data), sharing MOOC-knowledge, offering credit transfer, and ICT-services.

The actual staff of OpenupEd is very small. Activities are organized in collaboration with the partners, projects with the European Association of Distance Teaching Universities (EADTU), or hiring external experts. By sharing competencies and resources, the partners of OpenupEd are capable to apply for subsidies on national and supranational level. OpenupEd calls the participants in its portal "partners," whereas a label as "customers" could also be appropriate, as services are provided based on a fee. Essential for OpenupEd is the process of co-creation; the services they offer are dependent on the participation of their customers, whereas the value for their customers is the result or the services. Critical to this process is a large network of both similar and complementary partners.

While portals do not encourage openness in education, they can play an important role as they offer learners the possibility to find and compare courses, acting as a kind of "Educational Google." Additionally, they can offer the learners a guarantee of quality, by setting a system of standards for the MOOC-providers.

On the operational level, OpenupEd offers free MOOCs of good quality for learners. On the financial level, they offer services towards their members, partners, or customers, one of the services being the hosting. For these services OpenupEd is paid, with the free services reserved for beneficiaries (the learners), which are financed through a membership model and based on the desire of the members for a high-quality course environment.

Quality, credit transfer and standardization can only be realized by making your participants work together. One of the key competences of OpenupEd is the organizational quality and their relationship with HEI-non-members and subsidizers. However, part of their value-offer is the amount of traffic and learners they attract, which depends on the amount of courses, the quality, and the reputation of the partners. So, the quality and amount of courses determines the attraction for learners, whereas the amount of learners determines the earning potential of OpenupEd.

In the period 1995-1996, California State University (CSU) decided that they wanted to create an educational library for its 23 campuses. The main purpose of this library was to share educational instruments, resources, and teaching experiences. MERLOT was, and still is, financed by CSU (with support of Apple and the government). From the beginning on, the question asked was how to make the "library" attractive to the people contributing and using the resources. This was achieved by letting the communities be structured by the staff and faculty and not by the librarians and technological staff. Instead of allowing the producer to guess what is usable, they chose to let the user decide, in an aim to involve the users more over the producers (Hanley, 2013).

Of the total registered members, there are over 50,000 faculty, over 43,000 students, and over 11,000 staff. Diversity is guaranteed since anyone may contribute and review contributions. MERLOT is used by the California Open Online Library (www.cool4ed.org), which makes it easy to find free and open resources, as well as open access journal articles (http://coolfored.org/findjournalsandarticles.html).

From 1998 on, other institutions were interested in programs for faculty development and ICT-applications, which were developed as part of MERLOT. Several partners of MERLOT pay to use applications and for the advice of the MERLOT staff. In turn, this raises the effectivity and efficiency of MERLOT for CSU. About 50% of the MERLOT budget are subsidies, and the remaining 50% is earned offering different services. Similarly, there are institutions that pay for the development of learning environments. MERLOT offers customized services, websites, and specific materials to build affordable learning systems.

New is the website aimed at students, which offers a self-assessment that is used by different universities. It also offers courses based on the materials of MERLOT.org, information on courses offered by the participating HEIs, information on open access journals, etc. (see MERLOTX.org). The purposes of MERLOT are stated as strategic missions:

Producers, users, reviewers, and learners are combined in professional groups. To support the competences of different producers and users, MERLOT provides a community in ICT literacy on all kinds of ICT related skills (http://teachingcommons.cdl.edu/ictliteracy/). MERLOT stimulates quality and reviews of offered materials.

Community leaders were not assigned, but emerged from within the groups. MERLOT tries to identify these people and facilitates them in stimulating the community. These "key-producers" are involved in strategic decisions, the organization of the face-to-face conferences, and are given toll-free conference lines and other communication facilities. MERLOT rewards individuals by offering free access to conferences, by giving out awards, and naming best practices and contributors (http://grapevine.MERLOT.org/#news1). An indication of MERLOT's success is the fact that the majority of the original communities are still together.

Key competences in MERLOT are the ability to keep up to date on technological developments, to stimulate further community development, to stimulate the individual participation, and to communicate with individual members and groups. The original purpose of embedding open resources in the CSU system of 23 HEI's requires further managerial and social skills.

MERLOT developed several business models. Firstly, it defined openness as free sharing: teachers were seen as both producers and consumers of OER, creating a connection between supply and demand for OER. On an operational level, MERLOT makes communities the central focus; on the funding level, CSU and others continue to finance these communities.

The second business model builds on the competences that were developed through the first model: paying activities as developing programs for employers, developing new learning environments, and lastly introducing the OER materials in third party educational programs and making them available for students.

Aim of Lumen Learning is to increase openness by replacing costly textbooks of publishers with the help of OER. By helping HEIs to replace expensive textbooks by internally developed materials, based on free materials, Lumen Learning claims to improve students' success, pedagogical flexibility, and - at the same time - lower costs for students and the institutions.

Lumen Learning trains staff to customize available open resources. They feel that the usage of open resources is important because: "Education is a matter of sharing, and the open educational resources approach is designed specifically to enable extremely efficient and affordable sharing" (Wiley & Green, n.d.).

Their customers are diverse and interrelated (Lumen Learning, 2015). Firstly, Lumen Learning is hired and paid by HEIs for their activities; secondly, they train staff to adopt OER, replacing commercial books; and lastly, the students, or the end users, will be personally using these adopted materials.

The key activities of Lumen Learning are to provide instructions during the course development process, assist by the search for relevant materials, help with intellectual property rights issues, and with problems with respect to hosting, integration, and alike. Lumen Learning lists key resources as the (open) educational resources they have accumulated, their hosting platforms, their knowledge on open software, and their expertise with respect to several educational and managerial topics.

As for partnerships, Lumen Learning lists several open communities, institutional partners, funding partners, and research communities. Since the start of this research, Lumen Learning started a partnership with Follett, an organization with similar goals.

Organizations as Lumen Learning bridge the gap between the supply of (open) educational resources and the demand, by offering the necessary capabilities for applying these resources in different educational programs. Since this research began, more of these initiatives were brought to our attention. There is a Spanish organization, Humuork.lab, which aims to translate MOOCs into SPOCs for internal education of firms and e-learning experiences for companies and universities (http://www.homuorklab.com/en). In Texas, there are for-profit-organizations that help traditional universities to transform their face-to-face education into distance learning (Newbold & Angrove, 2017). Yet there seems to be a commercial market for reusing and redesigning open courses and resources for special groups.

The concept of openness seems to be dependent on the actual educational system and specific conditions. For OpenupEd, openness is viewed as an access to education for all learners, as European educational fees are relatively low. In the American context, fees are high and prohibitive, and textbooks are expensive. In this context, openness is defined as cost effective. Merlot and Lumen Learning offer materials as OER and MOOCs as alternatives to expensive books and materials. In the case of FemTechNet, openness in itself is not the goal. Openness is the result of the perceived need to collaborate in order to share information and resources through a community.

Another difference is the approach towards the users of OE; MOOCs are organized top-down. Their attractiveness for learners is determined by quality, certification, and diversity in subjects, which are determined by the producers of OE (OpenupEd, MERLOT). In the case of Lumen Learning, the paying customers (HEIs) determine what they want, while the end-users (beneficiaries, students) are part of the value-offering (without students, the materials would be meaningless), but they have no direct influence on the value-offering.

OpenupEd is comparable to Lumen Learning in the sense that their expenses are covered through participant contributions. These participants pay for the opening up of their MOOCs. The end-users (the learners) are not customers in themselves, but part of the value offering towards the participants.

MERLOT is a mixture of different models. The organization can be split into an OER part (MERLOT I) and a service provider (MERLOT II), aimed at offering paid services towards third parties. The financial base of MERLOT I is the structural collaboration with CSU. In the interview with Gerry Hanley (G. Hanley, personal communication, October 01, 2015), he talked about the large commitment towards the suppliers and users of the collections. These make up the organizational level of Merlot I. MERLOTs value offering towards them is the supporting networks and peer review mechanisms.

MERLOT is expanding its activities (the value-offering and its earning-potential of Merlot II) by offering skills training, LMS-design and student support adding another traditional single layer business model, in which the financer and the beneficiary are the same.

FemTechNet is a network based within a community. The way it is organized guarantees the influence of both users and producers; the value offering equals the demand of the participants. These determine, not only the courses and resources developed, but also control which to share and which not to. Again, the organizational level is ordered around different motives than the financial level.

Both OpenupEd and MERLOT put a lot of importance on the capability to develop networks, mobilizing the skills of the participants to realize the value offer. Both organizations offer quality and ICT support, so the key resources are ICT skills, the capability to build and support the development of educational materials (OER or MOOCs), and LMS and portal environments. Lumen Learning, OpenupEd, and MERLOT (II) require commercial skills to convince institutions to use their services, while FemTechNet strongly depends on their existing network of people and materials for the development and utilization of the DOCCs. Overall, the most important resource is the willingness to cooperate.

OpenupEd and MERLOT both share some semantic confusion as both organizations describe their paying members as partners. If an explicit distinction is made between those who pay for services and those who have a non-monetary relationship with the focus organization, then their stakeholders could be divided in "clients" or "users" (paying) and "partners" (non-paying). For OpenupEd, the members are clients, whereas EADTU and governments could also be viewed as partners. MERLOT identifies individuals and communities as partners, building its earning model on the relationships with paying HEIs (clients).

In the case of Lumen Learning, several partners are listed that compose the value scheme of this organization, with the most important being the individuals and communities who offer OER materials. In addition, they name several institutions, which finance studies into the effects of OER. One could discuss if this is a partnership, or an additional earning model, competing with several other research institutes studying the practices of OE. Through the individual members of FemTechNet, the network has several partners, including institutions that donated the subscription fees for BlueJeans, grants for research, and offer support for congresses and alike.

Based on these cases, it is not possible to formulate the business model for opening up, but some conclusions can be drawn. Table 2 gives a concise description of the role of unbundling in the four cases

Table 2

Results of the Case-Study

| Unbundling case | Costs approach | Income approach | Financial unbundling |

| FemTechNet | Sharing costs through collaboration. | Offering free resources, within a traditional curriculum; offering services as research, etc. | Community oriented (teachers and researchers): users become producers and producers become users. |

| OpenupEd | Divide traditional education (within the own organization) and MOOCs (OpenupEd). | Deriving income through offering shared services as hosting, offering of courses, quality control, and authoring tools. | Operational: learners Financial: HEIs. |

| MERLOT I: Database of OER | Sharing costs through collaboration. | Offering free resources, within a traditional curriculum; offering services as research, etc. | Community oriented (teachers): users become producers and producers become users. |

| MERLOT II: Service provider | Helps organizations to integrate open materials (OER) in their traditional programs, replacing textbooks and other paid materials. | Resources are offered free for individuals, but are used to offer services for HEIs. | A mix of learners, teachers (as users), and organizations as financiers. |

| Lumen Learning | Helps organizations to integrate open materials (MOOCs) in their traditional programs, replacing textbooks and other paid materials. | Service oriented: deriving income by transforming open resources into customized education within traditional programs. | A mix of learners, teachers (as users) and organizations as financiers. |

A problem with open education seems to be the demand for it. There are a lot of organizations offering either MOOCs or OER. Their success, as measured by sustainability, is dependent on the fit between value offerings and the objectives of the stakeholders. This can be done by the building of, or building on, a community. A community can consist of beneficiaries at the operational level, such as the teachers of MERLOT or the feminist teachers and learners of FemTechNet, yet can also be the financial stakeholders as in the OpenupEd MOOC approach. In the cases of Lumen Learning and Merlot II, open materials are used as an input in the services provided by the organizations, whereas the customers pay for the services (not for the materials). In this situation, the two-level business canvas reduces into the traditional business model canvas.

Based on these case studies, building a successful community would require a separate study, since it is important to have a shared strategic vision and a strong understanding of the target group. In contrast to traditional education, there are no formal requirements to offering OER or MOOCs, so participants have to voluntarily comply with different quality and entry requirements; there has to be a shared belief in the value of the collaboration.

To offer free materials, courses, or services requires key resources and activities. These resources and activities have to be financed, so these organizations must find ways to recruit financial stakeholders. To acquire the necessary funding, organizations have to help the financers to obtain their targets, for example, education for all, educating the workforce, or other targets. This will result in integrating the financier's goals into the value offering of the financial layer. Alternatively, the OE-organization can acquire funds by offering paid services based on the free resources, to finance the production of these resources.

Whether open education is a success should be measured on the satisfaction of both beneficiaries and financers. Whether OE will be sustainable in the future depends mainly on the satisfaction of the financing organizations.

The framework in the former paragraph is based on a small selection of cases. More cases could be analyzed, for example the American MOOC platforms or collaborating platforms such as OERu. The geographical scope of the study was restricted; cases of organizations in Africa (OER Africa, African Virtual University) and Asia (OER Asia, see for example Dhanarajan & Abeywardena, 2013) should be compared to the cases here. It is very well possible that other models could be distinguished.

Further to this, the question exists whether commercial firms, such as Lumen Learning and Homuork.lab, will improve the usage of open materials and the integration into traditional programs, or whether educational organizations will chose not-for-profit platforms such as OpenupEd or MERLOT to educate their teachers in the use of open materials. McGreal (2018) summarizes 13 case studies (teachonline.ca/tools-trends/open-education-resources-oer-applications-around-world/taxonomy-term), in terms of opportunities, benefits, challenges, and potential. These kinds of studies enlarge our working understanding of OE systems.

Another addition to this research should be an inquiry into the partners/customers of the three providers - MERLOT, OpenupEd, and Lumen Learning - to see if their strategic choices are in line with the desires and needs of users.

Lastly, another major research question is the role communities play in the sustainability of OE. It seems that OE created within a community increases the possibility of the long term sustainability. As MERLOT has already exists for 20 years, its top-down organization of communities should be described in more detail. Contrasting, FemTechNet is also based in a community, but has a bottom-up approach. Communities emerge organically around new topics and interests of the members. It will be interesting to see how both kind of approaches could be used to improve the effectiveness of open education in the future.

Burd, E., Smith, S. & Reisman, S. (2015). Exploring business models for MOOCs in higher education. Innovative Higher Education, 40(1), 37-49. doi: 10.1007/s10755-014-9297-0

Cengage Learning. (2016). Open educational resources (OER) and the evolving higher education landscape. White Paper. Retrieved from http://assets.cengage.com/pdf/wp_oer-evolving-higher-ed-landscape.pdf

Christensen, C., Johnson C., & Horn M. (2010). Disrupting class. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Christensen, C. M., Horn, M. B., Caldera, L., & Soares L. (2011). Disrupting college: How disruptive innovation can deliver quality and affordability to postsecondary education. Educational Technology Research and Development, 57(2), 267-269. doi: 10.1007/s11423-009-9113-1

Cormier, D. (2008). The CCK08 MOOC - Connectivism course, 1/4 way [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://davecormier.com/edblog/2008/10/02/the-cck08-mooc-connectivism-course-14-way/

Czerniewicz, L., Deacon, A., Glover, M., & Walji, S. (2017). MOOC - making and open educational practices. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29(1), 81-97. doi: 10.1007/s12528-016-9128-7

De Langen, F. (2008). Business cases in an electronic environment: Lessons for e-education? (Working paper no. GE 08-01), Heerlen: Open University.

De Langen, F. (2011). There is no business model for open educational resources: A business model approach. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 26(3), 209-222. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2011.611683

Dhanarajan, G., & Abeywardena I. S. (2013). Higher education and open educational resources in Asia: An overview. In G. Dhanarajan & D. Porter (Eds.), Open educational resources: An Asian perspective (pp. 3-18). Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11599/23

FemTechNet. (2013). Transforming higher education with distributed open collaborative courses (DOCCs): Feminist pedagogies and networked learning [White paper]. Retrieved from http://FemTechNet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/FemTechNetWhitePaperSept30_2013.pdf

Hanley, G. (2013). MOOCs, MERLOT, and open educational services. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2), pp. 1-2. Retrieved from http://jolt.merlot.org/vol9no2/hanley_message_0613.pdf

Hollands, F. M., & Tirthali, D. (2014). MOOCs: Expectations and reality. Full report. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/583b86882e69cfc61c6c26dc/t/58f6698fc534a5c049f8994c/1492543890763/MOOCs_Expectations_and_Reality.pdf

Jansen, D., & Goes-Daniels, M. (2016). Comparing institutional MOOC strategies. Status report based on a mapping survey conducted in October - December 2015. EADTU - HOME project. Retrieved from http://eadtu.eu/images/publicaties/Comparing_Institutional_MOOC_strategies.pdf

Juhasz, A., & Balsamo A. (2012). An idea whose time is here: FemTechNet - A distributed online collaborative course (DOCC), Ada, (1). doi: 10.7264/N3MW2F2J

Kelly, A. P., & Hess, F. M. (2013). Beyond retrofitting: Innovation in higher education. Washington, DC: Hudson Institute. Retrieved from http://www.hudson.org/content/researchattachments/attachment/1121/beyond_retrofitting-innovation_in_higher_ed_%28kelly-hess,_june_2013%29.pdf

Lumen Learning. (2015). Lumen learning open business model canvas. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/drawings/d/1l-kSBcCCupbBGOvxZkRy3hQkcnqZuLTmeFuMmlC3zwo/edit?pref=2&pli=1

Online Course Report. (2016). State of the MOOC 2016: A year of massive landscape change for massive open online courses [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.onlinecoursereport.com/state-of-the-mooc-2016-a-year-of-massive-landscape-change-for-massive-open-online-courses/

Marshall. S. (2012). Open education and systemic change. On the Horizon, 20(2), 110-116. doi: 10.1108/10748121211235769

Mazoué, J. G. (2014). Beyond the MOOC model: Changing educational paradigms [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2014/11/beyond-the-mooc-model-changing-educational-paradigms

McGreal, R., Miao F., & Mishra, S. (Eds.). (2016). Open educational resources: Policy, costs and transformation. Commonwealth of Learning, UNESCO. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002443/244365e.pdf

McGreal, R. (2018). A survey of OER implementations in 13 higher education institutions. Contact North/Contact Nord. Retrieved from https://oerknowledgecloud.org/sites/oerknowledgecloud.org/files/OER13paperJ16.pdf

Mulder, F., & Janssen B. (2013). Open (het) onderwijs (Opening up eduction). In R. Jacobi, H. Jelgerhuis & N. van der Woert (Eds.), Trendrapport OER 2013: open online onderwijs breekt door (Trendrapport OER 2013: open online education breaks through; pp. 38-44), Utrecht. Retrieved from https://www.surf.nl/binaries/content/assets/surf/nl/kennisbank/2013/Trendrapport+OER+2013_NL_+DEF+07032013+%28HR%29.pdf

Newbold, J., & Angrove W. (2017) Navigating the distance education landscape in 2017 and beyond. In L. Gómez Chova, A. Martínez & I. Torres (Eds.), INTED2017 proceedings (p. 971). Valencia: 11th International Technology, Education and Development Conference. doi: 10.21125/inted.2017.0382

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. New York: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2012.00977_2.x

Pappano, L. (2012, November 2). The year of the MOOC. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html

Salisbury, A. D. (2014). Impacts of MOOCs on higher education [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blog.edx.org/impacts-moocs-higher-education

Sanderse, J. (2014). The business model canvas of NGOs (Master's thesis, Open University). Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/6935967/The_business_model_canvas_of_NGOs_The_business_model_canvas_of_NGOs_door_Judith_Sanderse

Sheets, R. G., & Crawford, S. (2012). Harnessing the power of information technology: Open business models in higher education. Educause Review, 47(2). Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/~/media/files/article-downloads/erm1222.pdf

Sigalov, A., & Skuratov A. (2012). Educational portals and open educational resources in the Russian federation. Moscow, Russia: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://iite.unesco.org/pics/publications/en/files/3214704.pdf

UNESCO. (2002, July 1-3). Forum on the impact of open courseware for higher education in developing countries (Final Report). Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001285/128515e.pdf

UNESCO. (2012, June 20-22). The Paris OER declaration, world open educational resources (OER) congress. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CI/CI/pdf/Events/English_Paris_OER_Declaration.pdf

Wang, C. H., & Zhao, G. (2011). Open educational resources in the people's republic of China: Achievements, challenges and prospects for development. UNESCO. Retrieved from https://iite.unesco.org/pics/publications/en/files/3214700.pdf

Wiley, D., & Green, C. (n.d.). Why openness in education? [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/pathways/chapter/reading-why-openness-in-education/

Wiley, D., Green, C., & Soares, L. (2012). Dramatically bringing down the cost of education with OER: How open education resources unlock the door to free learning [Blog post]. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2012/02/07/11167/dramatically-bringing-down-the-cost-of-education-with-oer/

Sustainability of Open Education Through Collaboration by Frank H. T. de Langen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.