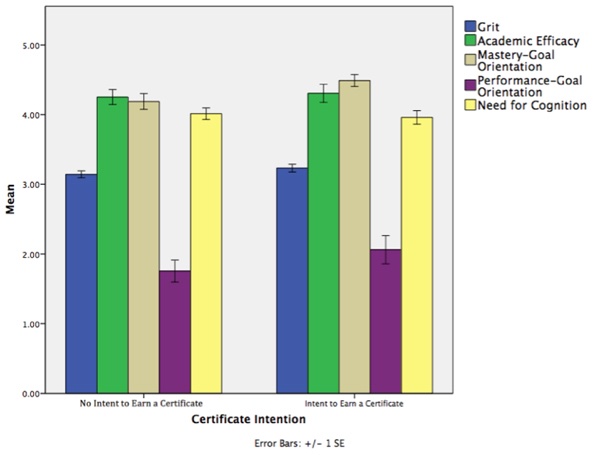

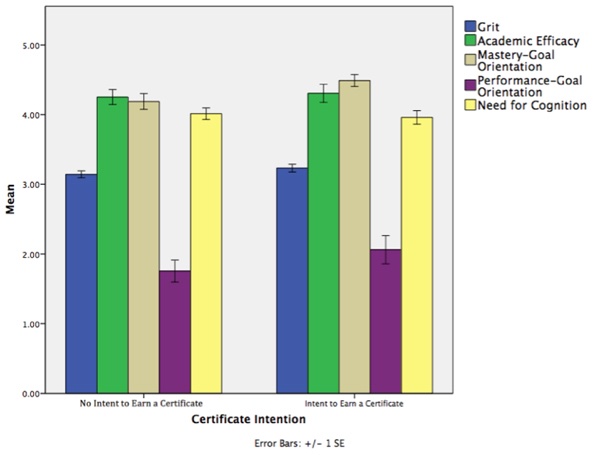

Figure 1. Mean differences of motivational factors between learners who intended to earn a certificate and those who did not.

Volume 19, Number 3

Yuan Wang1 and Ryan Baker2

1Arizona State University, USA, 2University of Pennsylvania, USA

In recent years there has been considerable interest in how many learners complete MOOCs, and what factors during usage can predict completion. Others, however, have argued that many learners never intend to complete MOOCs, and take MOOCs for other reasons. There has been qualitative research into why learners take MOOCs, but the link between learner goals and completion has not been fully established. In this paper, we study the relationship between learner intention to complete a MOOC and their actual completion status. We compare that relationship to the degree to which MOOC completion is predicted by other domain-general motivational factors such as grit, goal orientation, academic efficacy, and the need for cognition. We find that grit and goal orientation are associated with course completion, with grit predicting course completion independently from intention to complete, and with comparable strength.

Keywords: massive open online courses (MOOCs), online learning, learner motivation, learning analytics, grit

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) have gained considerable popularity in a relatively short time frame. Not all learners complete the MOOCs they start (DeWaard et al., 2011; Jordan, 2014; Knox, 2014; Pappano, 2012), yet MOOC completion has become an important addition to many learners' academic careers or professional development. A MOOC certificate can be a valuable step to earning course credits and credentials (Hyman, 2012). Furthermore, completing a MOOC can be beneficial towards eventually joining a scientific community of practice (Wang, Paquette, & Baker, 2014).

However, not all MOOC learners seem to be interested in completing the courses in which they enroll; many learners use MOOCs in more selective fashions, focusing on more specific sub-sets of the content and learning experience (Ho et al., 2014). It appears that learners approach MOOCs with a variety of goals and intentions (Breslow et al., 2013). Past MOOC learner motivation studies have analyzed the diverse range of motivation that MOOC learners bring to their studies. Kizilcec, Piech, and Schneider (2013) categorized MOOC learners into four groups based on their behavior: (1) completing; (2) auditing; (3) disengaging; and (4) sampling. Alternatively, Clow (2013) suggested that there is a "funnel of participation" with multiple levels of participation; the deeper the participation, the smaller the number of MOOC learners who reach that depth of participation. Although it is worth noting that many MOOC learners who do not complete or interact with the platform instead download course videos and study on their own (Kahan, Soffer, & Nachmias, 2017), suggesting that some learners may be more engaged with course materials than their in-platform behaviors seem to indicate.

Researchers have also explored various reasons behind the steep dropout rates among MOOC learners (e.g., Halawa, Greene, & Mitchell, 2014; Kizilcec, Pérez-Sanagustín, & Maldonado, 2017). For example, Alario-Hoyos, Estévez-Ayres, Pérez-Sanagustín, Kloos, and Fernández-Panadero (2017) examined the relationship between learner motivation and types of learning strategies and found out that MOOC learners, although often highly motivated in terms of both possessing intrinsic goals and high task value, may benefit from improved time management skills, especially given that MOOCs lack personalized support and instructor attention (Hood, Littlejohn, & Milligan, 2015).

More specific attention has also been given toward analyzing the types of motivation of MOOC learners who are working professionals (Milligan & Littlejohn, 2017). Their study identified that the majority of working professionals expressed that their interests lie in learning the course content to fill in their current skills gap and that these learners did not put course completion as their primary goal.

While these analyses showed that MOOC learners participate to varying degrees, they did not investigate whether the nonparticipating learners intended to complete the course at its outset. If a learner does not intend to complete the course, as with many of the learners in (Milligan & Littlejohn, 2017), perhaps their behavior should be interpreted differently. If a learner intended to complete the course, it is relevant to consider whether they actually did - and what factors lead some learners not to complete courses they planned at the outset to complete. Correspondingly, one can also ask if any learners in fact complete courses despite not initially intending to?

We can perhaps better understand the role played by learner intention, by comparing it to other learner goals and motivations. While research has shown that MOOC learners are often strongly internally motivated (Bonk & Lee, 2017), it has not yet shown which types of motivation play the largest role in either learner intent or outcomes. To investigate this, we can draw from the extensive literature on learner goals and motivation in other contexts. There have been MOOC studies that have examined domain-specific motivational concepts, such as whether the MOOC is relevant to the learner's academic field of study (e.g., Belanger & Thornton, 2013). Research in other domains has shown the important role of more cross-cutting aspects of motivation in driving participation and performance. For example, learning goals were shown to be associated with successful performance in traditional classroom settings (Pintrich, 2000). Learners with performance-approach goals may strive to outperform others; these goals were found to be positive predictors of exam performance. Conversely, learners with performance-avoidance goals may aim to avoid performing more poorly than others (Murayama, Elliot, & Yamagata, 2011). These goals were found to be associated with poorer performance (Elliot, McGregor, & Gable, 1999). Student motivation may also influence how they participate not just in the MOOC itself but in social media surrounding that MOOC (Sie et al., 2013).

Another important motivational construct - self-efficacy - has also been found to correlate with performance, for instance in mathematics (Hackett & Betz, 1989). Self-efficacy also predicts engagement within some online learning contexts (e.g., Eservel, 2014). Need for cognition (NFC) the extent to which individuals are inclined towards effortful cognitive activities, has also been found to positively relate to academic performance (Sadowski & Gülgös, 1996). More recently, grit has been found to predict retention in various contexts including school, workplace, and military (Eskreis-Winkler, Shulman, Beal, & Duckworth, 2014). These relationships have been insufficiently studied in the context of MOOCs. Studying the relationship between these variables and course completion may help us to understand the role that goal orientation and self-efficacy play in driving learner participation within MOOCs.

As such, the research in this paper attempts to investigate learner goals and motivations such as grit, goal orientation, academic efficacy, and NFC in the context of a MOOC, and in particular how these factors relate with and compare to the learner's own intention and plan to complete the MOOC. Specifically, the present study aims to answer the following questions: (1) How do initial learner intentions relate to subsequent course completion? and (2) How do other learner goals and motivational factors relate to subsequent course completion? Questions (1) and (2) lead to a third question: (3) How do these factors interact to produce a learner's choices which lead to completing a course and earning a certificate?

In the present study, we investigate three sets of variables: learner intention, motivation and goals, and MOOC completion. We first looked at the relation between learner intention and course completion; then we analyzed how motivational aspects relate to intention and completion, respectively. To guide the present study, we review related theoretical and empirical studies in two sections: Section 1 - Intention; and Section 2 - Four Motivational Variables Potentially Related to MOOC Completion: Goal Orientation, Self-efficacy, Grit, and NFC.

According to the theory of planned behavior, intentions are the most important predictor of behavior (Ajzen, 1985, 1991). In this case, we are interested in whether the learner completes the MOOC they start. However, people may have incomplete control over whether they can engage in the behaviors they intend (Sheeran, 2002).

To study the gap between intention and behavior, McBroom and Reid (1992) decomposed the consistency and discrepancy between intentions and subsequent actions into four categories (McBroom & Reid, 1992). Learners termed inclined actors intend to act and actually do so. Learners termed disinclined abstainers do not intend to act and indeed do not. These two groups of learners are consistent in their behavior. Inclined abstainers (who intend to act but fail to do so) and disinclined actors (who do not intend to act but actually do) can be seen as having behavior that is discrepant from their actions (Orbell & Sheeran, 1998). Sheeran (2002) conducted a meta-analysis and found that inclined abstainers are considerably more common than disinclined actors across contexts. The existence of a discrepancy between intention and behavior indicates that intention is not the only factor that influences subsequent behavior. Motivation has long been held to be a critical factor affecting the relationship between intention and behavior (Ajzen & Fisbbein, 1974). Therefore, in the present study, we investigate how learner intention interacts with various aspects of motivation.

Grit. Grit refers to "perseverance and passion for long-term goals" (Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews, & Kelly, 2007, p. 1087). Studies have shown that grit is associated with achievement motivation (Duckworth & Eskreis-Winkler, 2013), educational attainment (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009), and professional achievement (e.g., Vallerand, Houlfort, & Forest, 2014). Grit also predicts retention in a challenging 3-week military training course (Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2014). Grit has not yet been widely studied in the context of MOOCs. One study investigated grit within MOOC learners who were currently enrolled in college, finding among male learners that grit was associated with the plan to graduate from college (Cupitt & Golshan, 2015); however, this research did not investigate the relationship between grit and MOOC completion. Another study (Hicks & Klemmer, 2016) employed the Grit Scale (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009) as one component in constructing a learning-belief scale to assess MOOC learners; no analysis was, however, conducted on grit alone. As such, it remains an open question how grit affects retention in the context of MOOCs.

Academic efficacy. A second important motivational factor is self-efficacy, defined as one's belief that one can accomplish a given task (Bandura, 1994). Zimmerman, Bandura, and Martinez-Pons (1992) found evidence that a learner's self-efficacy is associated with learning achievement. A specific category of self-efficacy is academic efficacy: self-efficacy focused on academic situations (Ryan, Gheen, & Midgley, 1998; Pintrich & Schunk, 1996). In the context of MOOCs, a previous study (Wang & Baker, 2015) found little evidence for difference in generalized academic efficacy between MOOC completers and noncompleters, but they found evidence that MOOC completers had higher self-efficacy in completing the current MOOC prior to the start of the course.

Goal orientation. There is a long history of research into learner motivation in education (cf. Ames & Archer, 1988; Ames, 1992). One of the most popular theoretical frameworks for learner motivation over the last three decades has been the study of learner goals, or goal orientation (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1994). Dweck (1986) argued that two key goals characterize most learners: (1) learning goals (also called mastery goals); and (2) performance goals. Learners with learning goals strive to increase their competence and master skills (Ames & Archer, 1987); learners with performance goals strive to succeed and obtain favorable assessments from others. In the context of MOOCs, a previous study (Wang & Baker, 2015) found little evidence for the difference in goal orientation between MOOC completers and noncompleters. We investigate in this study whether this finding can be replicated and how it connects to learner intention.

Need for cognition (NFC). NFC indicates a stable tendency to engage in and enjoy effortful cognitive activity (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982). MOOCs may represent this effortful activity for many learners. Several past studies have shown that NFC predicts learners' academic achievement (e.g., Sadowski & Gülgös, 1996; Elias & Loomis, 2002). NFC has been found to be positively related to goal-oriented behavior (Fleischhauer et al., 2010). Moreover, NFC was found to be positively associated with the experience of flow in human-computer interactions (Li & Browne, 2006). Overall, NFC has been studied most thoroughly in off-line learning contexts (Evans, Kirby, & Fabrigar, 2003), though there has been some research in the context of computer-assisted learning contexts (e.g., Li & Browne, 2006). To the best of our knowledge, this construct has not been studied in the context of MOOCs.

We collected pre-course survey measures including learner intention types and various motivational aspects, as well as learner course completion statuses. We then conducted two sets of comparisons. The first set looked into how learners with different intention types differ regarding their motivational survey responses; the second set investigated how course completers and noncompleters differ regarding their motivational survey responses.

We researched the proposed questions within the context of the second iteration of the Big Data in Education Course (BDEMOOC), developed by Teachers College, Columbia University via the edX MOOC platform. BDEMOOC's second iteration begun began on July 1, 2015. It officially ended on August 26, 2015, but the course remained open after that point. A survey was distributed to learners through the course e-mail messaging system to learners who enrolled in the course prior to the course start date. Completion was predefined in the syllabus as the equivalent of earning a certificate. Therefore, in the present paper, intention to completion and intention to earn a certificate are interchangeable. While a verified certificate was available for a fee, an unofficial certificate was available for free.

This MOOC was comprised of 8 weeks of video lectures, discussion forums, and a set of 8 assignments (completed weekly). The videos taught learners key methods for analyzing large-scale educational data. Some of the videos contained in-video quizzes that did not count toward the final grade. In each assignment, learners were asked to conduct an analysis of a data set provided to them (typically genuine data from educational settings) and answer step-by-step questions about the results of their analysis.

The 8 weekly assignments incorporated on-demand hints and instant feedback delivered through the Cognitive Tutor Authoring Tool (CTAT) integrated with edX through Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI) integration (Aleven, McLaren, Sewall, & Koedinger, 2009). All the weekly assignments involved numeric input or multiple-choice questions and were automatically graded. Assignments had automated messages that were given when learner input reflected a known misconception or error, and each step of the assignments had on-demand hint messages that explained the process to the learner (Aleven et al., 2015). A set of 8 weekly collaborative chat activities were delivered through the Bazaar tool (Adamson, Dyke, Jang, & Rosé, 2014). The Bazaar tool provides a chat environment that matches learners into discussion groups guided by a virtual agent. However, due to technical glitches, the activities in the Bazaar tool were not graded, and this policy shift was announced early in the course.

The course had a total enrollment of 10,348 students from 162 countries during its official run as a course. During the first week of the course, 2,538 learners visited at least one page of course content, and 1,212 learners played at least one video. There were 510 learners who posted at least one comment in the discussion forum during the course. The course data showed that 251 out of the 2,548 learners who visited at least one page of course content completed at least one assignment, and that 116 learners in total completed the online course and received a certificate.

Completion was also coded as a dichotomous variable, where 1 = certificate earners and 0 = noncertificate earners. The requirement for earning a certificate in the BDEMOOC was predefined as earning an overall grade average of 70% or above. The overall grade was calculated by averaging the learner's 6 highest grades out of a total of 8 assignments.

To measure MOOC learner motivation, the precourse survey incorporated three sets of questions:

On the first day of the course, all enrolled learners received an e-mail with a link to participate in the precourse survey. This survey received 2,792 responses; 38% of the respondents were female and 62% of the respondents were male. All survey respondents were 18 years of age or older; 9% were between 18 to 24 years, 38% were between 25 to 34 years, 26% were between 35 to 44 years, 17% were between 45 to 54 years, 8% were between 55 to 64 years, and 1% were 65 years or older. This indicates a learner profile not too dissimilar to the graduate learner populations taking more traditional online courses. Respondents were not required to complete any items in the survey and, as such, different numbers of students completed each instrument: 256 respondents completed the entire Grit Scale; 491 respondents completed the entire academic efficacy scale; 625 respondents completed the entire mastery-goal orientation scale; 417 respondents completed the entire performance-goal orientation scale; and 213 respondents completed the entire NFC Scale; 1,116 respondents responded to the question regarding their completion intentions.

Enrollment intention. Upon entering the precourse survey, we asked learners to indicate whether they intended to earn a certificate or not. Enrollment intention was coded as a dichotomous variable, where 1 = certificate intenders and 0 = noncertificate intenders.

The Grit Scale. The present study included the 8-item short Grit Scale (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009) to assess learner' consistency of interests and perseverance of efforts. Consistency of interests was measured by items such as "New ideas and projects sometimes distract me from previous ones" - a reverse-coded item - while perseverance of efforts was measured by items such as "I'm a hard worker." The grit scores were calculated by averaging across items on a scale of 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate more grit.

Three PALS subscales: Academic efficacy, mastery-goal orientation, and performance-goal orientation. Three PALS (Midgley et al., 2000) scales measuring mastery-goal orientation and academic efficacy were used to study standard motivational constructs. PALS scales have been widely used to investigate the relation between a learning environment and a learner's motivation (cf. Clayton, Blumberg, & Auld, 2010; Meece, Anderman, & Anderman, 2006; Ryan & Patrick, 2001). For the present study, three subscales measuring academic efficacy, mastery-goal orientation, and performance-goal orientation were included to investigate the differences between MOOC course completers and noncompleters. In total, fifteen items (five in each scale), scaled 1 to 5, were included. Scores for measuring academic efficacy, mastery-goal orientation, and performance-goal orientation were computed by averaging across the 5 items under each subscale.

The NFC Scale. The 18-item NFC Scale has been widely used as a motivational factor in hundreds of empirical studies of effortful cognitive endeavors (Cacioppo, Petty, Feinstein, & Jarvis, 1996). The NFC Scale scores were computed by averaging across all 18 items, on a scale of 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate more NFC.

After survey data collection, data on course completion was merged with the survey data. We studied the relationship between certificate intention and certificate completion. Two sets of independent t tests were conducted to compare in terms of the five motivational variables, grit, academic efficacy, two types of goal orientation, as well as NFC listed above (1) certificate intenders and noncertificate intenders and (2) certificate earners and noncertificate earners.

As this investigation comprises 10 statistical analyses across two groups, we controlled for multiple comparisons, using Benjamini and Hochberg's (1995) false discovery rate (FDR) method. FDR methods attempt to adjust the degree of conservatism across tests so that 5% of significant tests are false positives, instead of attempting to validate that each test individually has less than a 5% chance of being a false positive, given other tests. This ensures a low overall proportion of false positives, while avoiding the substantial overconservatism found in methods such as the Bonferroni correction (see Perneger, 1998 for a review of the criticisms of the Bonferroni correction).

In this study, two levels of baseline statistical significance (α =.05 or .1) for the Benjamini & Hochberg (B & H) adjustment were used. The .05 level suggests full statistical significance, while .1 indicates marginal significance. In the B & H adjustment, each test retains its original statistical significance, and the adjusted α value cutoff for significance changes depending on the order of test significance. Adjusted α value cutoffs are given in tables in the following section.

A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relation between intention to earn a certificate and actual certificate attainment. The relationship between these two variables was significant - χ2 (1, N = 1232) = 7.879, p <.01 - indicating that intention is associated with completion. This result is consistent with our hypothesis that learners who intend to complete the course are more likely to actually complete the course.

Table 1

Results of Chi-square Test Between Types of Learner Intention and Course Completion

| Noncertificate earners | Certificate earners | |

| Noncertificate intenders | 894 (72.6%) | 80 (6.5%) |

| Certificate intenders | 222 (18.0%) | 36 (2.9%) |

Note. χ2 = 7.879, df = 1. *p <.01

Of the 20.9% of learners who intended to complete the course 14.0% actually completed the course and 86.0% did not complete the course. Of the 79.1% of learners who did not intend to complete the course 8.2% actually completed the course and the remaining 91.8% did not complete the course.

Academic efficacy, mastery-goal orientation, and performance-goal orientation were found to be statistically significantly different between certificate intenders and noncertificate intenders. Among the five motivational factors, three out of five were found to be statistically significant:

(1) academic efficacy: t(489) = 3.048, p =.003 (α =.015), d =.238; (2) mastery-goal orientation: t(623) = 6.826, p <.0001 (α =.0005), d =.503; and (3) Performance-Goal Orientation: t(415) = 3.824, p <.001 (α =.01), d =.307.

The degrees of freedom varied test-by-test depending on the number of subjects who answered the items on each scale. It is interesting to see that certificate intenders are more likely to be both mastery-goal oriented and performance-goal oriented. Since intention was measured at the beginning of the course, one possible interpretation is that learners who intend to earn a certificate are interested in both learning the content of the course and in proving their competency with the content.

Grit (t[254] = 1.476, p =.141 [α =.035], d =.191) and NFC (t[211] = -.605, p =.546 [α =.045], d =.088) were not statistically significantly different between learners who intended to obtain a certificate and learners who did not intend to obtain a certificate. It appears that grit is not strongly associated with one's intention of intended future achievement but more associated with the actual achievement. This may suggest that grit has an impact on a persistence that the learners themselves are not fully aware of, driving the learner to almost compulsively complete tasks they begin even when they do not initially intend to.

Table 2

Comparison of Motivational Scales Between Certificate Intenders and Noncertificate Intenders

| Survey items | Certificate intention | t test, p value (α level adjusted) | |

| No | Yes | ||

| Grit | M = 3.168, SD =.378 | M = 3.236, SD =.335 | t(254) = 1.476, p =.141 (α =.035) |

| Academic Efficacy | M = 3.952, SD =.797 | M = 4.139, SD =.776 | t(489) = 3.048, **p =.003 (α =.015) |

| Mastery-Goal Orientation | M = 3.963, SD =.856 | M = 4.345, SD =.648 | t(623) = 6.826, **p <.0001 (α =.0005) |

| Performance-Goal Orientation | M = 1.804, SD =.966 | M = 2.128, SD = 1.136 | t(415) = 3.824, **p <.001 (α =.01) |

| NFC | M = 4.039, SD =.591 | M = 3.985, SD =.637 | t(211) = -.605, p =.605 (α =.045) |

Note. Boldface indicates items with statistically significant relationship between these two groups. Significant: **p < adjusted α. Marginally significant: *p < adjusted α *2.

Figure 1. Mean differences of motivational factors between learners who intended to earn a certificate and those who did not.

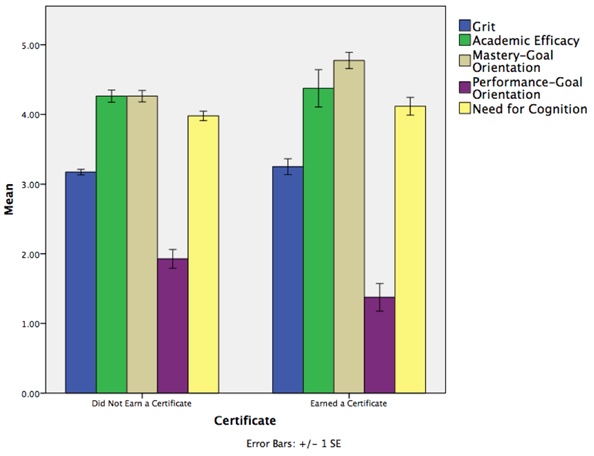

Both grit (t[254] = 2.005, p =.046 [α =.03]) and mastery-goal orientation (t[145] = 1.435, *p =.039 [α =.025], d =.307) were marginally significantly associated with obtaining a certificate with a moderately large effect size (d =.528), while performance-goal orientation (t[145] = -1.038, **p =.005 [α =.02], d =.369) was statistically significantly associated with obtaining a certificate. Specifically, certificate earners scored higher on grit and mastery-goal orientation but lower on performance-goal orientation. Academic efficacy (t[142] = -1.751, p =.144 [α =.04], d =.212) and NFC (t[26] = -1.540, p =.605 [α =.05], d =.122) did not show statistically-significant differences between learners who completed the course and those who did not. This set of findings are consistent with past literature: grittier learners are more likely to earn a certificate and mastery-goal orientated learners are more likely to earn a certificate whereas performance-goal oriented students are less likely to earn a certificate.

Table 3

Comparison of Motivational Scales Between Certificate Earners and Noncertificate Earners

| Survey items | Earned a certificate? | t test, p value (α level adjusted) | |

| No | Yes | ||

| Grit | M = 3.184, SD =.364 | M = 3.355, SD =.277 | t(254) = 2.005, *p =.046 (α =.03) |

| Academic efficacy | M = 4.025, SD =.794 | M = 3.858, SD =.794 | t(142) = -1.751, p =.144 (α =.04) |

| Mastery-goal orientation | M = 4.071, SD =.818 | M = 4.309, SD =.729 | t(145) = 1.435, *p =.039 (α =.025) |

| Performance-Goal Orientation | M = 1.934, SD = 1.044 | M = 1.585 SD =.835 | t(145) = -1.038, **p =.005 (α =.02) |

| NFC | M = 4.027, SD =.599 | M = 3.948, SD =.692 | t(26) = -1.540, p =.605 (α =.05) |

Note. Boldface indicates items with statistically significant between these two groups. Significant: **p < adjusted α. Marginally significant: *p < adjusted α *2.

Figure 2. Mean differences of motivational factors between those who earned a certificate and those who did not.

As a follow-up, three logistic regression analyses were conducted to test whether grit, mastery-goal orientation, and performance-goal orientation can individually predict if a learner earns a certificate or not while controlling learner intention.

For the first logistic regression analysis (Table 4, below), a test of the full model against a constant-only model was statistically significant (χ2[2] = 7.676, p =.022) indicating that grit scores and intention types together as a set distinguished between learners who earned a certificate and those who did not. The Wald test results showed that grit (χ2[1] = 3.481, p =.062) and intention types (χ2 [1] = 3.272, p =.070) were individually each marginally statistically significant and positively associated with obtaining a certificate within the combined model. Their strength of association was approximately the same, but the magnitude of effect, shown by the B coefficients, was larger for grit than certificate intent. This result indicates that, among learners who intend to earn a certificate, grittier learners are still more likely to finally earn a certificate, in line with initial expectations.

Table 4

Logistic Regression Analysis of Earning a Certificate or Not from Grit and Intention Types

| Covariates | B | SE | Wald | df | p value | Exp(B) |

| Grit | 1.410 | .756 | 3.481 | 1 | .062 | 4.096 |

| Certificate intent | .900 | .498 | 3.272 | 1 | .070 | 2.460 |

| Constant | -7.603 | 2.547 | 8.913 | 1 | .003 | .000 |

For the second logistic regression analysis (Table 5, below) looking into how mastery-goal orientation and intention types relate to earning a certificate or not, a test of the full model against a constant only model was statistically significant (χ2[2] = 30.738, p <.001) indicating that mastery-goal orientation and intention types together as a set distinguished between learners who earned a certificate and those who did not. The Wald test results showed that mastery-goal orientation was not statistically significant within the combined model (χ2[1] =.854, p =.355) while intention type was statistically significant and positively associated with obtaining a certificate within the combined model, χ2[1] = 23.971, p <.001). This result is expected since the majority of the MOOC learners can be expected to be interested in the content of the course (few learners take an advanced MOOC to fulfill a requirement). Additionally, mastery-goal driven learners may not all aim to earn a certificate. It is quite possible that some of the mastery-goal driven learners are only interested in a subsection of the course, explaining why they did not complete the course and earn a certificate.

Table 5

Logistic Regression Analysis of Earning a Certificate or Not From Mastery-goal Orientation and Intention Types

| Covariates | B | SE | Wald | df | p value | Exp(B) |

| Mastery-goal orientation | .195 | .211 | .854 | 1 | .355 | 1.215 |

| Certificate intent | 1.531 | .313 | 23.971 | 1 | <.001 | 4.625 |

| Constant | -4.152 | .897 | 21.424 | 1 | <.001 | .016 |

For the third logistic regression analysis (Table 6, below) looking into how performance-goal orientation and intention types relate to earning a certificate or not, a test of the full model against a constant only model was statistically significant (χ2[2] = 40.440, p <.001) indicating that performance-goal orientation and intention types together as a set distinguished between learners who earned a certificate and those who did not. The Wald test results showed that performance-goal orientation (χ2[1] = 9.333, p =.002) and intention types (χ2[1] = 31.358, p <.001) were individually each statistically significant within the combined model. Performance-goal orientation was negatively associated with earning a certificate while intention types were positively associated with earning a certificate. The magnitude of effect, shown by the B coefficients, was larger for certificate intent than performance-goal orientation. This result indicates that learners who are more performance-goal oriented are less likely to earn a certificate. It is possible that some learners who may learn better in environments that are more akin to the traditional face-to-face classrooms where their performance can be visibly demonstrated to fellow learners and instructors. The reduced opportunities to interact with fellow learners and instructor in the MOOC context may lead to a dwindled motivation in learning for these performance-oriented learners.

Table 6

Logistic Regression Analysis of Earning a Certificate or Not From Performance-Goal Orientation and Intention Types

| Covariates | B | SE | Wald | df | p value | Exp(B) |

| Performance-goal orientation | -.551 | .180 | 9.333 | 1 | .002 | .576 |

| Certificate intent | 1.713 | .306 | 31.358 | 1 | <.001 | 5.547 |

| Constant | -2.414 | .356 | 45.856 | 1 | <.001 | .089 |

Consistent with past studies examining the relation between intention and behavior (e.g., Orbell & Sheeran, 1998), a learner's intention of earning a certificate is associated with actually earning a certificate in this MOOC. However, there remains a gap between intention and behavior in this MOOC setting. As in Sheeran's (2002) work on the imbalance between intention and behavior, it was more common for learners to fail to earn certificates despite their intention to earn a certificate than it was for learners to earn a certificate despite their intention not to earn a certificate. It appears that many of the learners who earned certificates without intending to do so were high in grit. Fully understanding this pattern of results is an important topic for future work; we discuss this further below. Moreover, many learners did not intend to complete the course and did not complete the course. It is worth asking: What were these learners' goals for the course? Developing a typology of the types of learners who never intend to complete MOOCs will be an important step towards understanding these learners in their full complexity and serving their learning needs as effectively as possible.

Learners who intended to obtain a certificate differ from learners who did not intend to obtain certificates in terms of both mastery goals and performance goals. Specifically, learners who intended to obtain certificates were likely to be higher both in mastery-goal orientation and in performance-goal orientation than learners who did not intend to obtain certificates.

Grit was not significantly different between the learners who intended to complete the course, and the learners who did not intend to complete the course (despite the relationship between grit and course completion). But academic efficacy was higher for learners who intended to earn certificates than learners who did not intend to earn certificates.

Need for cognition was not significantly different between the learners who intended to complete the course and those who did not. Both of these groups of learners rated NFC highly. This result is somewhat expected since learners voluntarily decide to take a MOOC and gain little extrinsic benefit from doing so, compared to many other activities that they could choose. Therefore, it is plausible that most MOOC learners would exhibit a strong NFC.

Certificate earners showed marginally significantly higher grit than learners who did not earn certificates, with a fairly large effect size. A follow-up analysis showed that grit and intention independently predict whether or not a learner earns a certificate. It is interesting to note that grit was associated with completion even though it was not associated with intention. One possible interpretation of this result is that not all gritty learners intend to complete the course, but that their grit leads them to do so anyways. Once the learner starts the activity, their drive to complete what they start overrides their initial intention. For instance, it is possible that some high-grit learners intend to study only a subsection of the course, but that their grit led them to study the rest as well. Collecting qualitative data on these learners' experience may help us to better understand why these learners do choose to complete the course, despite their initial plans and intentions.

Both mastery goals and performance goals were significantly different between certificate earners and learners who did not earn certificates. Specifically, certificate earners reported being higher in mastery-goal orientation than learners who did not earn certificates. By contrast, learners who did not earn certificates reported being higher in performance-goal orientation than certificate earners. However, both certificate earners and noncertificate earners scored low on the performance-goal orientation subscale. It is worth noting that performance goals were positively associated with certificate intention but negatively associated with actual completion. It is possible that some learners who intend to earn a certificate might wish to do so in order to demonstrate their capability and obtaining favorable judgments from others. It is also possible that performance-avoidance goals, the goal of avoiding failure (Elliot, 1999), may have played a role in the lower completion; the PALS scale used in this research does not distinguish between different types of performance goals. Fully understanding the relationship between goal orientation and course completion in MOOCs will likely require further research with an instrument that distinguishes between types of performance goals.

In this paper, we find that certificate earners rated themselves higher on the mastery-goal orientation and lower on performance goal orientation. These results are consistent with past literature when the same set of constructs were measured in traditional learning contexts such as in-person classrooms (e.g., Pintrich, 2000). This pair of results enrich the understanding of how broadly the relationships between goal orientations and learning outcomes are consistent.

However, performance goals were found in our study to negatively correlate with obtaining a certificate, whereas previous work in other settings has found that performance goals correlate positively with learning outcomes (e.g., Harackiewicz, Barron, Tauer, Carter, & Elliot, 2000). Since performance goals are related to judgment on one's ability relative to others (Midgley, Kaplan, & Middleton, 2001), the relative lack of peer and instructor contact identified in the MOOC environment (e.g., Alario-Hoyos et al., 2017) may alter the impacts of learners' performance-goal orientation. In particular, learners may compare themselves to the most knowledgeable participants in the course, those who frequently post to the forums, rather than the silent majority of MOOC learners, making students believe they are performing worse than they actually are, and thereby reducing their motivation to complete.

The relationships seen between completion and goal orientation, however, contradict the results of a previous study of goal orientation in MOOCs conducted in an earlier version of the same MOOC, which did not find relationships between goal orientation and course completion (Wang & Baker, 2015). This may be due to the different formats of the assignments. The version of the course studied in this paper used intelligent tutoring system-based assignments with automated help including step-by-step guidance, as discussed above. By contrast, the version of the course studied in the previous study (Wang & Baker, 2015) did not include the same level of support for the assignments; its assignments were the type of quiz-style assignments typically seen in the Coursera and edX platforms. Therefore, a different set of learners might plausibly have completed activities when this additional support was present. Additionally, the two iterations of the course were hosted on two different MOOC platforms (Coursera versus edX), which might also have contributed to the different results, given the many differences in design and population served between the two platforms.

Academic efficacy was not found to be statistically significantly different between learners who earned certificates and learners who did not earn certificates. Instead, both certificate earners and nonearners generally have high academic efficacy. The lack of a finding here is somewhat surprising since past studies in other learning settings have found that higher academic efficacy is associated with higher learning outcomes (e.g., Multon, Brown, & Lent, 1991). But as pointed out in other articles (Breslow et al., 2013), many learners learn in MOOCs but choose not to complete the course.

There was also not a significant difference in NFC between certificate earners and learners who did not earn certificates. The same lack of finding was seen for intention. MOOC learners generally rated NFC highly, regardless of whether they earned a certificate or intended to do so.

As such, goal orientation and grit appeared to be associated with MOOC completion, but other motivational variables did not seem to have that same relationship.

The research presented in this paper related MOOC completion to learner intention to complete, goal orientation, grit, and other motivational variables. Several findings were obtained, but it is important to note that the present study only explored the relationship between these variables within the context of a single MOOC. Considering this, future work should collect and analyze data from different MOOCs across disciplinary areas to determine whether findings obtained in the present study are general. Doing so remains challenging, as many MOOCs give only brief precourse surveys, or no surveys at all; encouraging MOOC instructors and developers to add more extensive surveys has the potential to move research in this field forward.

In addition, further analyses should also take into consideration the different reasons why a learner may enroll in a MOOC while not intending to earn a certificate. It will be valuable going forward to more thoroughly investigate the diversity of reasons why learners enroll in MOOCs in order to better assess whether a MOOC is succeeding for all its learners. Past studies have identified distinct learner groups based on behavior (Kizilcec et al., 2013). It might also be useful to directly ask whether a learner intends to only study a subsection of the course - perhaps even a single video - or to only use some types of resources. This type of question could be answered through broader questionnaires, perhaps given after course completion; follow-up interviews with learners may help reveal even more insights by allowing us to probe the reasons behind specific choices. Additionally, better understanding of learner intention types can help enable psychological researchers to better track, model, and ultimately understand learner behavioral patterns relevant to each of the activities a learner expresses an intention to participate in. For instance, it can be useful to use analytics and knowledge engineering methods to investigate further within the course logs whether a learner who intends to study only a sub-section of the course actually watches more videos and completes more assignments relevant to that sub-section. By doing so, the relationship between learner intention and MOOC participation can be understood in a finer-grained fashion in order to tailor MOOCs better to all of the learners who use them.

This work was supported by the National Sciences Foundation, Award #DRL - 1418378, Collaborative Research: Modeling Social Interaction and Performance in STEM Learning.

Adamson, D., Dyke, G., Jang, H. J., & Rosé, C. P. (2014). Towards an agile approach to adapting dynamic collaboration support to learner needs. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 24(1), 91-121.

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11-39). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Ajzen, I., & Fisbbein, M. (1974). Factors influencing intentions and the intention-behavior relation. Human Relations, 27(1), 1-15.

Alario-Hoyos, C., Estévez-Ayres, I., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Kloos, C. D., & Fernández-Panadero, C. (2017). Understanding learners' motivation and learning strategies in MOOCs. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(3), 119-137. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i3.2996

Aleven, V., McLaren, B. M., Sewall, J., & Koedinger, K. R. (2009). A new paradigm for intelligent tutoring systems: Example-tracing tutors. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 19, 105-154.

Aleven, V., Sewall, J., Popescu, O., Xhakaj, F., Chand, D., Baker, R.,... & Gasevic, D. (2015).The beginning of a beautiful friendship? Intelligent tutoring systems and MOOCs. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (pp. 525-528). Springer.

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and learner motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261.

Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Learners' learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(3), 260.

Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1987). Mothers' beliefs about the role of ability and effort in school learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(4), 409-414.

Bandura, A. (1994). Self‐efficacy. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Belanger, Y., & Thornton, J. (2013). Bioelectricity: A quantitative approach Duke University's first MOOC. Retrieved from http://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/handle/10161/6216

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 289-300.

Bonk, C. J., & Lee, M. M. (2017). Motivations, achievements, and challenges of self-directed informal learners in open educational environments and MOOCs. Journal of Learning for Development, 4(1), 36-57.

Breslow, L., Pritchard, D. E., DeBoer, J., Stump, G. S., Ho, A. D., & Seaton, D. T. (2013). Studying learning in the worldwide classroom: Research into edX's first MOOC. Research & Practice in Assessment, 8, 13-25.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1).

Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., Feinstein, J. A., & Jarvis, W. B. G. (1996). Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals varying in need for cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2).

Clayton, K., Blumberg, F., & Auld, D. P. (2010). The relationship between motivation, learning strategies and choice of environment whether traditional or including an online component. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(3), 349-364.

Clow, D. (2013). MOOCs and the funnel of participation. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (pp. 185-189). ACM.

Cupitt, C., & Golshan, N. (2015). Participation in higher education online: Demographics, motivators, and grit. Paper presented at the STARS Conference 2015, Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved from http://www.unistars.org/papers/STARS2015/09C.pdf

DeWaard, I., Abajian, S., Gallagher, M., Hogue, R., Keskin, N., Koutropoulos, A., & Rodriguez, O. C. (2011). Using mLearning and MOOCs to understand chaos, emergence, and complexity in education. International Review of Research in Open & Distance Learning, 12(7), 94-115.

Duckworth, A. L., & Eskreis-Winkler, L. (2013). True grit. APS Observer, 26(4).

Duckworth, A.L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M.D., & Kelly, D.R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1087-1101. Retrieved from http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~duckwort/images/Grit%20JPSP.pdf

Duckworth, A.L, & Quinn, P.D. (2009). Development and validation of the short Grit Scale (GritS). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91, 166-174. Retrieved from http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~duckwort/images/Duckworth%20and%20Quinn.pdf

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040.

Dweck, C. S. (2010). Mind-Sets and Equitable Education. Principal Leadership, 10(5), 26-29.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256.

Elias, S. M., & Loomis, R. J. (2002). Utilizing need for cognition and perceived self‐efficacy to predict academic performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(8), 1687-1702.

Elliot, A. J. (1999). Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educational Psychologist, 34(3), 169-189.

Elliot, A. J., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (1994). Goal setting, achievement orientation, and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(5), 968.

Elliot, A. J., McGregor, H. A., & Gable, S. (1999). Achievement goals, study strategies, and exam performance: A mediational analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 549.

Eskreis-Winkler, L., Shulman, E. P., Beal, S. A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2014). The grit effect: Predicting retention in the military, the workplace, school and marriage. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(36), 1-12.

Eservel, U. Y. (2014). IT-enabled knowledge creation for open innovation. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 15(11), 805.

Evans, C. J., Kirby, J. R., & Fabrigar, L. R. (2003). Approaches to learning, need for cognition, and strategic flexibility among university learners. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 73(4), 507-528.

Fleischhauer, M., Enge, S., Brocke, B., Ullrich, J., Strobel, A., & Strobel, A. (2010). Same or different? Clarifying the relationship of need for cognition to personality and intelligence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(1), 82-96.

Hackett, G., & Betz, N. E. (1989). An exploration of the mathematics self-efficacy/mathematics performance correspondence. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 20, 261-273. doi: 10.2307/749515

Halawa, S., Greene, D., & Mitchell, J. (2014). Dropout prediction in MOOCs using learner activity features. eLearning Papers, 37, 7-16.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M., Carter, S. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2000). Short-term and long-term consequences of achievement goals: Predicting interest and performance over time. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 316-330.

Hicks, C. M. & Klemmer, S. (2016). Beliefs about learning: Critical for success in online courses. UC San Diego The Design Lab.

Ho, A. D., Reich, J., Nesterko, S., Seaton, D. T., Mullaney, T., Waldo, J., & Chuang, I. (2014). HarvardX and MITx: The first year of open online courses. (HarvardX Working Paper No. 1) Retrieved from http://harvardx.harvard.edu/multiple-course-report

Hood, N., Littlejohn, A., & Milligan, C. (2015). Context counts: How learners' contexts influence learning in a MOOC. Computers & Education, 91, 83-91.

Hyman, P. (2012). In the year of disruptive education. Communications of the ACM, 55(12), 20-22.

Jordan, K. (2014). Initial trends in enrolment and completion of massive open online courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(1), 133-160. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v15i1.1651

Kahan, T., Soffer, T., & Nachmias, R. (2017). Types of participant behavior in a massive open online course. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(6), 1-18. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i6.3087

Kizilcec, R. F., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., & Maldonado, J. J. (2017). Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behavior and goal attainment in massive open online courses. Computers & Education, 104, 18-33.

Kizilcec, R. F., Piech, C., & Schneider, E. (2013, April). Deconstructing disengagement: Analyzing learner subpopulations in massive open online courses. In D. Suthers, K. Verbert, E. Duval, & X. Ochoa (Eds.), Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (pp. 170-179). ACM.

Knox, J. (2014). Digital culture clash: "massive" education in the E-learning and Digital Cultures MOOC. Distance Education, 35(2), 164-177.

Li, D., Browne, G. J., & Wetherbe, J. C. (2006). Why do internet users stick with a specific web site? A relationship perspective. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 10(4), 105-141.

McBroom, W. H., & Reid, F. W. (1992). Towards a reconceptualization of attitude-behavior consistency. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55, 205-16.

Meece, J. L., Anderman, E. M., & Anderman, L. H. (2006). Classroom goal structure, student motivation, and academic achievement. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 487-503.

Midgley, C., Kaplan, A., & Middleton, M. (2001). Performance-approach goals: Good for what, for whom, under what circumstances, and at what cost? Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 77.

Midgley, C., Maehr, M. L., Hruda, L., Anderinan, E.M., Anderman, L., Freeman, K. E. ... Urdan, T. (2000). Manual for the patterns of adaptive learning scales (PALS). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Milligan, C., & Littlejohn, A. (2017). Why study on a MOOC? The motives of learners and professionals. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(2), 92-102. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i2.3033

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(1), 30.

Murayama, K., Elliot, A. J., & Yamagata, S. (2011). Separation of performance-approach and performance-avoidance achievement goals: A broader analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(1), 238.

Orbell, S., & Sheeran, P. (1998). "Inclined abstainers": A problem for predicting health-related behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 151-65.

Pappano, L. (2012). The year of the MOOC. The New York Times, 2(12).

Perneger, T. V. (1998). What's wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 316(7139).

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(3).

Pintrich, P.L., & Schunk, D. H. (1996). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and application. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54-67.

Ryan, A. M., Gheen, M. H., & Midgley, C. (1998). Why do some students avoid asking for help? An examination of the interplay among students' academic efficacy, teachers' social-emotional role, and the classroom goal structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 528.

Ryan, A. M., & Patrick, H. (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents' motivation and engagement during middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 38(2), 437-460.

Sadowski, C. J., & Gülgös, S. (1996). Elaborative processing mediates the relationship between need for cognition and academic performance. The Journal of Psychology, 130(3), 303-307.

Sheeran, P. (2002). Intention-behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), 1-36. doi: 10.1080/14792772143000003

Sie, R. L., Pataraia, N., Boursinou, E., Rajagopal, K., Margaryan, A., Falconer, I., ... Sloep, P. B. (2013). Goals, motivation for, and outcomes of personal learning through networks: Results of a tweetstorm. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 16(3).

Vallerand, R. J., Houlfort, N., & Forest, J. (2014). Passion for work: Determinants and outcomes. In M. Gagne (Ed.), Oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self-determination theory (pp. 85-105). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Wang, Y., & Baker, R. (2015). Content or platform: Why do students complete MOOCs? Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 11(1).

Wang, Y., Paquette, L., & Baker, R. (2014). A longitudinal study on learner career advancement in MOOCs. Journal of Learning Analytics, 1(3), 203-206.

Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663-676.

Grit and Intention: Why Do Learners Complete MOOCs? by Yuan Wang and Ryan Baker is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.