Volume 18, Number 5

Catherine Cronin

National University of Ireland, Galway

Open educational practices (OEP) is a broad descriptor of practices that include the creation, use, and reuse of open educational resources (OER) as well as open pedagogies and open sharing of teaching practices. As compared with OER, there has been little empirical research on individual educators' use of OEP for teaching in higher education. This research study addresses that gap, exploring the digital and pedagogical strategies of a diverse group of university educators, focusing on whether, why, and how they use OEP for teaching. The study was conducted at one Irish university; semi-structured interviews were carried out with educators across multiple disciplines. Only a minority of educators used OEP. Using constructivist grounded theory, a model of the concept "Using OEP for teaching" was constructed showing four dimensions shared by open educators: balancing privacy and openness, developing digital literacies, valuing social learning, and challenging traditional teaching role expectations. The use of OEP by educators is complex, personal, and contextual; it is also continually negotiated. These findings suggest that research-informed policies and collaborative and critical approaches to openness are required to support staff, students, and learning in an increasingly complex higher education environment.

Keywords: open educational practices, open educational resources, open education, higher education, OEP

Openness in education attracts considerable attention and debate. Much recent research has focused on MOOCs, open educational resources (OER), social media in education, and concomitant issues related to data, privacy, ethics, and equality (Moe, 2015; National Forum, 2015; Stewart, 2015; Weller, 2014; Wiley, Bliss, & McEwen, 2014). The potential benefits and limits of open education are widely reported in the literature and explored briefly in this paper. However, there is a lack of empirical data about the use of open educational practices (OEP), particularly in institutions without open education policies. OEP is a broad descriptor that includes the creation, use and reuse of OER, open pedagogies, and open sharing of teaching practices. Veletsianos (2010) notes that educators can shape and/or be shaped by openness. It is this individual meaning-making and praxis that I explore in this study.

The qualitative, empirical study explores meaning-making and decision-making by university educators regarding whether, why and how they use open educational practices. It is a study not only of open educators, but also of a broad cross-section of academic staff at one university. The purpose is to understand how university educators conceive of, make sense of, and make use of OEP in their teaching, and to try to learn more about, and from, the practices and values of educators from across a broad continuum of "closed" to open practices.

The paper begins with a review of the literature, exploring interpretations of openness in education. I pay particular attention to the various definitions of open educational practices (OEP) and provide a theoretical framework for exploration of them. Following this, I describe the results of an empirical study of a diverse cross-section of academic staff across multiple disciplines, focusing on whether, why and how they use OEP. The paper ends with general conclusions of the study as well as implications for higher education practitioners, researchers, managers and policy makers.

Education is about sharing knowledge; thus, openness is inherent in education. But what exactly is "open education?" According to the Open Education Consortium (n.d.): "open education encompasses resources, tools and practices that employ a framework of open sharing to improve educational access and effectiveness worldwide." Yet open education narratives and initiatives have evolved in different contexts, with differing priorities. Thus, open education often means subtly or substantively different things to different people. The qualifier "open" is variously used to describe resources (the artefacts themselves as well as access to and usage of them), learning and teaching practices, institutional practices, the use of educational technologies, and the values underlying educational endeavours. Weller (2014) advises that we are mistaken to try to define or discuss openness as a unified entity; it is more useful as an umbrella term. Watters (2014) cautions that while such multivalence can be a strength, it is also a weakness when the term "becomes so widely applied that it is rendered meaningless." Conducting and studying research on open education thus requires that we identify the precise interpretation(s) and contexts of openness being explored.

Four broad interpretations of openness within the context of higher education can be identified across the literature. Following is a brief summary of these four interpretations: open admission, open as free, open educational resources (OER), and open educational practices (OEP). This is followed by a deeper exploration of OEP, the focus of this study.

Open admission. One interpretation of openness is open admission to formal education. The qualifier "open" refers to open-door academic policies; that is, elimination of entry requirements for institution-based learning, as in "open university." No prior educational attainment is required for entry to open universities, although course fees generally apply. Open universities often make educational resources available to the public for free (an example of the second interpretation of open education, described below), historically via television, radio, and more recently the internet.

Open as free. A second interpretation of openness describes educational resources that are available for free, i.e. at no cost to the user. This level of openness is an extension of the idea of public libraries and the internet as a free and open resource for all. Under this interpretation a vast array of online resources and courses would be considered open; for example, YouTube videos, TED Talks, Khan Academy screencasts, MOOCs, etc. (Moe, 2015). These educational resources are freely available online to anyone interested in and, not insignificantly, able to access them. In many cases (e.g., most MOOC providers) users are required to register, providing personal information such as a name and email address. In such cases, while resources are technically free, they have an opportunity cost to the user in the form of personal data and usage data (Hodgkinson-Williams & Gray, 2009). In addition, the use of free online resources is subject to copyright restrictions unless the creators provide explicit permission for reuse of the original works. Many open education advocates and researchers thus consider "open as free" to be a limited interpretation of openness (Wiley, 2009; Winn, 2012), leading to a third interpretation: open educational resources or OER.

Open educational resources (OER). According to the Open Education Consortium (n.d.), openness is not simply a matter of access but "the ability to modify and use materials, information and networks so education can be personalized to individual users or woven together in new ways for large and diverse audiences" (para. 6). This change in the conception of openness is often described as the difference between open as gratis (free of cost) and open as libre (enabling legal reuse) (Winn, 2012). The term "open educational resources" or OER, first coined in 2002, defines resources that expressly enable reuse through the use of open licensing or release into the public domain (Wiley et al., 2014). Open licensing, typically via a Creative Commons license, means that resources can be altered, reused and/or repurposed to suit requirements within specific contexts, depending on the exact terms of the license. These usage rights are defined as the "5 Rs of Openness:" Retain, Reuse, Revise, Remix, and Redistribute (Wiley et al., 2014). Thus, while openness in OER is focused on freedom, the degrees of freedom available within a particular license can vary (Lane, 2009). Multiple studies have shown a low but slowly increasing level of awareness and acceptance of OER among academic staff in higher education (Allen & Seaman, 2016; National Forum, 2015; Reed, 2013; Rolfe, 2012). Overall, the focus of OER is on educational content, leading to a fourth interpretation of openness: open educational practices or OEP.

Open educational practices (OEP). Open education practitioners and researchers describe OEP as moving beyond a content-centred approach, shifting the focus from resources to practices, with learners and teachers sharing the processes of knowledge creation (Beetham, Falconer, McGill, & Littlejohn, 2012; Deimann & Sloep, 2013; Ehlers, 2011; Geser, 2007; Lane & McAndrew, 2010). A widely used definition of OEP, arising from the OPAL project (2011), is provided by Ehlers (2011): "practices which support the (re)use and production of OER through institutional policies, promote innovative pedagogical models, and respect and empower learners as co-producers on their lifelong learning paths (p. 4)." Research studies deal with this broad definition of OEP in various ways. Some focus primarily on the OER aspects of OEP (Armellini & Nie, 2013; Atenas, Havemann, & Priego, 2014; Hogan, Carlson, & Kirk, 2015; Karunanayaka, Naidu, Rajendra, & Ratnayake, 2015; Murphy, 2013; Schreurs et al., 2014). Other studies explore broader aspects of OEP such as open pedagogies and learning in open networks (Casey & Evans, 2011; Nascimbeni & Burgos, 2016; Veletsianos, 2015; Waycott, Sheard, Thompson, & Clerehan, 2013) and power relations and inequality (Czerniewicz, Deacon, Glover, & Walji, 2017; Rowe, Bozalek, & Frantz, 2013; Smyth, Bossu, & Stagg, 2016).

The scope of OEP continues to evolve rapidly. Education researchers across many domains have described and theorized some or all of the practices defined here as open educational practices using a variety of definitions and theoretical frameworks. These include open scholarship (Veletsianos & Kimmons, 2012b; Weller, 2011), networked participatory scholarship (Veletsianos & Kimmons, 2012a), open teaching (Couros & Hildebrandt, 2016), open pedagogy (DeRosa & Robison, 2015; Hegarty, 2015; Rosen & Smale, 2015; Weller, 2014), and critical digital pedagogy (Stommel, 2014). All are emergent scholarly practices that espouse a combination of open resources, open teaching, sharing, and networked participation. I have drawn from research in all of these areas to inform my work. I use the following definition of OEP in this study: collaborative practices that include the creation, use, and reuse of OER, as well as pedagogical practices employing participatory technologies and social networks for interaction, peer-learning, knowledge creation, and empowerment of learners.

This study draws on both sociocultural and social realist theories. From a sociocultural perspective, human activities are viewed as social practices situated within particular social, cultural, and historical settings (Lewis, Enciso & Moje, 2007). Openness is a sociocultural phenomenon, as is higher education; both are situated in and reflect their specific contexts and cultures (Peter & Deimann, 2013; Siemens & Matheos, 2010). A sociocultural framework is used by Veletsianos (2010, 2015) and Veletsianos and Kimmons (2012a, 2012b) to explore agency and context in their work on the practices and complexities of open, networked, participatory scholarship. In this study, I explore individual agency as well as the relationship between agency and structure. Building on the work of other open education researchers (see Cox, 2016; Cox & Trotter, 2016; Hodgkinson-Williams & Gray, 2009), I have found Archer's (2003) social realist theory to be a useful framework. Archer's work identifies three interdependent strata of reality: structure (e.g., institutional systems, policies), culture (e.g., norms, ideas, beliefs), and agency (individual freedom to act). According to Archer's (2003) "morphogenetic cycle," the interrelations between structure, culture, and agency occur over time. The powers of structure and culture exist but are only activated when human agents seek to act. Human reflexivity is the mechanism that mediates between structure and agency, moving from confronting constraints to elaborating a course of action (Archer, 2003).

The goal of this study is to understand why, how, and to what extent academic staff use, or do not use, open educational practices. The scope of the study is the use of OEP for teaching: it does not include other aspects of OEP such as open research or open publishing. The study posed the following research questions:

The study used qualitative research methods, specifically constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) to explore these questions. Grounded theory method, originally developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967), aims to build useful theory from empirical observations; "ground" refers to the grounding of findings in rigorous qualitative inquiry and analysis. Underpinned by interpretivist epistemology, grounded theory is a systematic, inductive, and comparative approach for conducting inquiry (Charmaz, 2006). Key aspects include the constant comparative method (comparing data with data, data with codes, codes with codes, codes with categories, etc.) and the generation and emergence of theory from what is observable in the data (Charmaz, 2006, 2014; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Mavetera & Kroeze, 2009). In constructivist grounded theory, as pioneered by Charmaz (2006), reality is recognized as multiple and interpretive rather than singular and self-evident. Thus, "generalisations are partial, conditional and situated in time and space" (Charmaz, 2006, p. 141). Storytelling is key: the focus is on participants' interpretations of their experiences. Overall, however, the goal of all grounded theory method is to generate concepts that explain the way people resolve their central concerns (Charmaz, 2014; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). For this study, the central concern relates to making sense of openness and the use of OEP for teaching. The constructivist grounded theory approach was used for sampling, interviewing, and analysis.

The study took place at one higher education institution in Ireland: a medium-sized, research-focused, campus-based university offering both undergraduate and postgraduate degrees. Although an increasing number of courses are offered in online and blended learning formats, the majority of the university's courses are offered on campus. The university uses a well-known Virtual Learning Environment (VLE, i.e., learning platform). In terms of institutional structure and culture with respect to openness, there were no policies or strategies related to open access publishing or OER at the time at which interviews were conducted for this study.

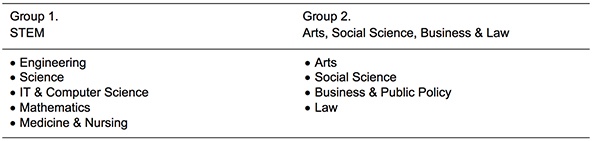

Participants were members of academic staff across a broad range of disciplines. Rather than exploring the practices of open educators only, I sought to explore the practices of educators along a continuum of "closed" to open practices. Open sampling was used initially to maximize diversity across three categories: gender, discipline area, and employment status. Firstly, an equal representation of female and male participants was invited to participate. Secondly, participants were invited from across two broad discipline areas using Biglan's (1973) typology of disciplines: hard and soft, pure and applied (further developed by Becher & Trowler, 2001; Trowler, Saunders, & Bamber, 2012; and others). Participants were invited equally from two groups: Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines and Arts, Social Science, Business and Law disciplines. The breakdown of disciplines is shown in Table 1. Finally, for the purposes of the study I defined the term "academic staff" broadly as: individuals employed by the university with responsibility for teaching, regardless of whether they were employed full-time or part-time, on permanent, fixed-term, or no contracts.

Table 1

Discipline Groups

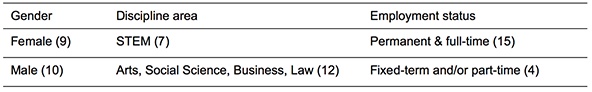

Later in the interviewing and analysis process, participants were selected using theoretical sampling, a process in grounded theory whereby data is jointly collected, coded and analysed so the researcher can decide what data to search for and to collect next in order to saturate each emerging category/concept (Charmaz, 2014; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Hallberg, 2006). The total number of participants is not predetermined; it is determined by theoretical saturation of the emerging theory. A total of 19 academic staff participated in the study. The breakdown across the three categories is shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Participants (19)

Using a semi-structured interview protocol I interviewed all participants, face-to-face, between August and December 2015. Each interview lasted approximately one hour and was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. In constructivist grounded theory, data and analysis are seen as social constructions reflecting both the participant and the researcher (Charmaz, 2014; Hallberg, 2006). Data were analyzed in an iterative manner. Interview transcripts were initially hand coded using open, inductive coding methods. Using the constant comparative method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), data analysis was undertaken concurrently with data gathering. Results of early interviews enabled refinement of interview questions for subsequent interviews. New codes were added as they emerged and previous transcripts were checked for these codes. I continued this process until I could not identify any new codes, categories or themes; that is, the point of data saturation was reached. NVivo 10 was used to facilitate data management and visualisation, the move from codes to categories, and the development of themes.

Charmaz (2014) identifies four criteria for evaluating grounded theory studies: credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness, with the first two increasing the value of the latter two. I reflected on and shared my own positionality with participants as an open educator/researcher, presently engaged in critical, qualitative, open education research. I also constructed the study so that participants could review stages of the research as it progressed. Each participant received their interview transcript as well as early stages of the concept model and analysis, and was invited to correct, clarify, or expand these. Three participants made minor changes or suggestions; fifteen returned specific affirming comments. All additions and changes suggested by participants were incorporated into the transcript records and analysis. These aspects of the study reflect a commitment to accountability and ethical research practice, but also contribute to the credibility the findings. Lather (1991) notes that returning to participants with initial findings, as well as systematic interaction between researcher and participants, lessens the possibility that researchers will impose meanings on situations and data instead of mutually constructing meanings with those they are studying.

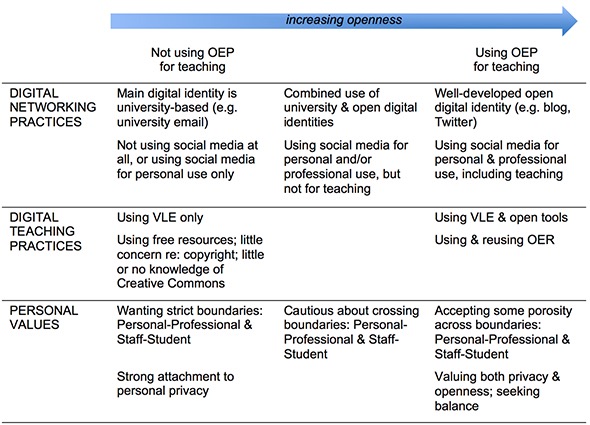

Participants described a wide range of digital and pedagogical practices and values; a summary of these is shown in Table 3. It is impossible to draw a clear boundary between educators who do and do not use OEP. Instead there is a continuum of practices and values ranging from "closed" to open. A complex picture emerges of a broad range of educators: some open (in one or more ways), some not; some moving towards openness (in one or more ways), some not; but all thinking deeply about their digital and pedagogical decisions. This concurs with other research findings that configurations of openness are uneven and diverse on both organizational (Ehlers, 2011) and individual (Veletsianos, 2015) levels. Overall, for the participants in this study, "using OEP" was primarily characterized by: having a well-developed open digital identity; using social media for personal and professional use, including teaching; using both a VLE and open tools; using and reusing OER; valuing both privacy and openness; and accepting some porosity across personal-professional and staff-student boundaries.

Table 3

Summary of Participants' Digital and Pedagogical Practices and Values on a Continuum of Increasing Openness

Fewer than half of the educators participating in the study (8 of 19) used OEP. Based on participants' own descriptions, two distinct forms of "using OEP" could be discerned: (i) being open, and (ii) explicitly teaching openly. All 8 open educators in the study demonstrated the former; a small subset also demonstrated the latter. All participants using OEP described being open with students; that is, being visible online, interacting and sharing resources in open online spaces. Each has an open digital identity and shared at least one of their profiles with students. A small subset of participants who used OEP chose not only to be open with their students but also to teach openly; that is, to create learning and/or assessment activities in open online spaces beyond the VLE. Teaching openly took different forms; for example, inviting students to engage in discussion via Twitter, creating courses in WordPress blogs, and encouraging students to share their work openly.

Participants across the spectrum of "closed" to open practices cited both pedagogical and practical concerns regarding the use of OEP. These included lack of certainty about the pedagogical value of OEP, concerns about students' possible over-use of social media, reluctance to add to their already overwhelming academic workloads, concerns about excessive noise in already busy social media streams, and concerns about context collapse (Marwick & boyd, 2010), both for themselves and for students. While many participants who were open educators acknowledged potential risks to using OEP, they considered the benefits to outweigh the risks. Participants who used OEP described what they perceived to be the benefits for students; these included: feeling more connected to one another and to their lecturer, making connections between course theory/content and what's happening in the field right now, sharing their work openly with authentic audiences, and becoming part of their future professional communities.

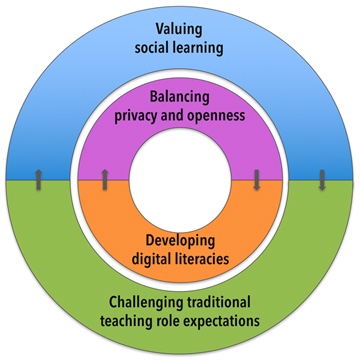

After exploring the extent to which participants used open practices and their reasons for choosing OEP or not, the analysis turned towards the third research question. What dimensions (values, practices, strategies) were shared by participants who used OEP, if any? The study of a diverse group of participants proved immensely useful here. Comparisons could be made not only among educators who used open practices, but also between those who used open practices and those who did not. Four dimensions emerged of participants who used OEP: balancing privacy and openness, developing digital literacies, valuing social learning, and challenging traditional teaching role expectations. The first two dimensions appear to be interdependent, as do the latter two. The four dimensions (see Figure 1) were shared variously by many of the participants, however all four were evident in each of the participants who used OEP. These are described briefly below and the first dimension is explored in detail in the Discussion section.

Figure 1. Four dimensions shared by educators using OEP.

Dimension #1. Balancing privacy and openness. Striving for a balance between privacy and openness emerged as the primary issue of concern for participants in this study. Although participants overall defined privacy in different ways, none said they did not value privacy. Strategies for managing privacy ranged from non-use of social media altogether to using particular digital practices in order to manage it (hence the link to Dimension #2). Those who used OEP described a variety of strategies for balancing privacy and openness, as networked individuals and networked teachers. Interaction in open online spaces tends to blur the boundary between different identities and roles. Participants described boundary-keeping activities in two domains, personal-professional and staff-student.

Most participants expressed a preference for a maintaining a boundary between their personal and professional digital identities and activities. Many wanted to avoid mixing streams of conversations about work with other conversations about family, social activities, sports, politics, etc. This mixing of streams, defined by Marwick and boyd (2010) as context collapse, is described by Vitak (2012) as "the flattening out of multiple distinct audiences in one's social network, such that people from different contexts become part of a singular group of message recipients (p. 451)." Some participants accepted a degree of context collapse or porosity across the personal-professional boundary; for example, work colleagues becoming friends online as well as offline. However, an ongoing challenge for many was managing interactions along this boundary; that is, the liminal space between the personal and the professional. Overall, participants described various ways of managing a personal-professional boundary, including using privacy settings, maintaining different Facebook profiles (professional and personal), and using different tools for different purposes (typically Facebook for private/personal, Twitter for public/professional).

While many participants spoke of the importance of communicating with and supporting students, most also described their desire to maintain some kind of staff-student boundary, both online and offline. Most participants felt it was "safest" to communicate online with students via the VLE and email only. Those using OEP tended to interact with students in open online spaces rather than personal online spaces. This was evident in the number of participants who said they do not "friend" students on Facebook. However, some created Facebook pages/groups or separate professional Facebook profiles to work around this. Twitter was seen as open and public and thus more acceptable by some as a tool for staff-student interaction.

Dimension #2. Developing digital literacies. Another dimension shared by many participants, including all who used OEP, was developing digital literacies, for self and students. Jisc (2015) defines digital literacies as "capabilities which fit someone for living, learning and working in a digital society (para. 3);" for example, ICT proficiency; information, media and data literacy; digital creation, communication and collaboration; digital learning and personal/professional development; and digital identity and wellbeing. Many participants said they would like to develop stronger or "better" digital identities. Some felt unsure of how to do this, or how do it well. Many said simply that they did not have enough time to develop their digital identities. This was often associated with feelings of guilt:

I should have much more. I should have my own web presence, a comprehensive presence. I just haven't gotten around to it - like 101 other things on my list, you know? (participant 3, not using OEP)

Participants who used OEP had well-developed and open digital identities and tended to be proficient users of social media. In addition to building their own digital literacies to communicate, collaborate, learn, and teach, many also sought to develop the digital literacies of their students, exploring issues such as digital culture and privacy.

Dimension #3. Value social learning. A third dimension shared by all who used OEP and many other participants was valuing social learning. Theories of social learning such as social constructivism and sociocultural theory emphasise the importance of learners being actively involved in the learning process (Conole & Oliver, 2006; McLoughlin & Lee, 2010). Many academic staff value social learning, whether or not they explicitly identify their teaching philosophies as such. Most participants in this study described their efforts to move away from a didactic lecturing style and to encourage more student engagement. Not all participants who encouraged social learning used OEP in their teaching. Many sought to create social learning activities in their classrooms and some tried to do this within the VLE. Thus, while all participants who used OEP valued social learning, the reverse was not true.

Dimension #4. Challenging traditional teaching role expectations. Finally, participants who used OEP described various ways that they challenged traditional teaching role expectations. Some spoke in terms of having a broader identity, seeing themselves as learners as well as teachers. One open educator spoke of trying to break down the traditional barrier between lecturer and student, another of using open practices explicitly as a way of expressing care for students. In these cases, challenging traditional teaching role expectations may be seen as a corollary to valuing social learning (Dimension #3), but this is not always the case. It also can be a way of working around structural barriers. Adjunct academic staff, for example, may not have reliable access to institutional email or the VLE. In such cases, alternative communication channels must be used. One participant described this vividly:

I don't let students know I'm on Twitter, they seem to figure it out. It depends on what email account I reply to them with. Depending on the teaching or contractual situation in any given year, sometimes the [university] email account just evaporates and I have to fall back and use my own email account. My personal email signature has my Twitter name, my blog - the [university] account just has the department name. (participant 8, using OEP)

These findings are explored in more detail in the following section.

This study explored meaning-making and decision-making by university educators regarding whether, why and how they use open educational practices for teaching. A number of academics used OEP; the majority did not. Participants spoke about privacy and openness - their interpretations of these and the relationship between them - more than any other aspect of digital, networked practice. Across all participants, both using and not using OEP, there was recognition that balancing privacy and openness is an individual decision and an ongoing challenge. In the words of one participant: "you're negotiating all the time."

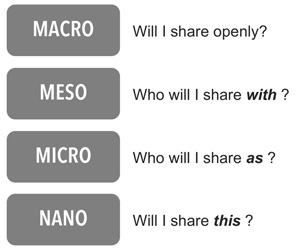

Analysis showed that participants sought to balance privacy and openness in their use of social and participatory technologies at four levels: macro (global level), meso (community/network level), micro (individual level), and nano (interaction level). Differentiating between these levels proved helpful in understanding decision-making around open practices (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Considering openness at four levels.

At the macro level, individuals make decisions about whether or not to engage in open sharing and networking. Some opt out at this level, while those who engage in open practice must consider questions at three further levels. At the meso level, individuals consider whom they would like share with (e.g., family, friends, colleagues, students, community/interest groups, the wider public) as well as those with whom they do not want to share. At the micro level, individuals make decisions about their digital identities, i.e. who they will share as. And at the nano level, individuals decide whether to interact/share something particular: for example, post, tweet, or retweet; use a specific tag or hashtag; like, follow, or friend.

Considering these four levels - macro, meso, micro, and nano - proved helpful in understanding the personal and complex negotiations involved in open educational practices. Formal and informal professional development initiatives often focus at the top or macro level; that is, describing the benefits of sharing, and supporting staff in learning how to use various tools. But the complex and ongoing work of open practice happens beneath this level, at the meso, micro, and nano levels, where issues around context collapse and digital identity are negotiated. A few examples from this study are included below, to illustrate.

At the macro level, educators who do not use open practices may have various reasons for choosing not to share openly. For example, three participants in this study recounted incidences of bullying and/or stalking experienced by members of their families, citing these as reasons for their strong attachment to personal privacy and limited/non-use of social media. Others described wanting simply to avoid the noise of open streams:

It's not just a question of privacy. It's a question of having a bit of time or space for myself. I need a tremendous amount of solitude... I need an awful lot of time to think. (participant 10, not using OEP)

At the meso level, where individuals decide whom to share with, many participants recounted how they used Facebook. In some cases, decision-making was clear-cut:

I definitely don't accept friend requests from people I don't know... Facebook does have personal information, family photographs, things like that. You just don't want to share with the world. (participant 19, using OEP)

In other cases participants described more nuanced decisions, influenced by the social norms in their discipline:

I've used privacy settings to block certain things that I post from professional colleagues on Facebook. But I still accept their invitations because I think it would be rude not to. (participant 11, using OEP)

At the micro level, decisions regarding openness relate specifically to an individual's sense of their own digital identity and their sense of agency in managing that identity. Some participants who were open educators saw the merits of having an open digital identity and sharing this with students:

I don't mind having all these profiles or students being able to look me up or know something about me. I think that's probably positive.... It's part and parcel of being an academic. (participant 17, using OEP)

Others have well-developed open digital identities but do not view these as integral to their roles as educators:

I don't mind if students follow me and if they find stuff that I've written online. But I just don't encourage it as part of the teaching, or their relationship with me as their teacher. (participant 5, not using OEP)

Digital identity issues raised in this study concur with findings from previous studies by Veletsianos (2013) and others indicating "an increasing tension between personal and professional identity, the spectrum of sharing that lies between the two, and the perception of what a scholar is and what she/he does" (p. 44).

Finally, at the nano level, individuals make decisions about individual open transactions; for example, "Will I share this ?" For many participants in this study, regardless of their level of openness, open practice is experienced as a process of continual reflection and negotiation, and occasionally anxiety:

It's not that I think people in the quad are watching our every move or anything like that. But occasionally you do think, maybe I'll be careful. (participant 14, not using OEP)

Open practice is not a one-time decision. It is a succession of personal, complex, and nuanced decisions. Individuals will always be motivated by personal values. As illustrated in this study, individual agency with respect to openness is influenced by both structure and culture. In an institution without an explicit strategy or policy regarding openness, individual educators were influenced by that absence as well as by disciplinary cultural norms and broader social norms when exercising their agency with respect to open practice.

Many open practitioners characterize openness as not just a practice but an ethos, a way of being, a commitment to democratic practices (e.g., Mackness, 2013; Neylon, 2013). While this may be the underlying motivation for many open educators, it is not a valid assumption for all open educators. Adjunct academic staff, for example, operate with a different set of structural constraints. For some, lack of access to institutional tools may act as a driver to adopt open practices; others may choose to avoid the risks of open practice due to the precarious nature of their positions.

One aspect of OEP which did not emerge in a significant way in this study was the use of OER. None of the participants spontaneously mentioned OER or open licensing. Where sharing of resources arose during interviews, I asked participants about their use of open resources. Discussion of copyright, licensing, and OER then ensued. This suggests that the relationship between OER and OEP may be more complex than sometimes conceived. Wiley (2015) notes that use of OER leads to OEP. This study suggests that the reverse can also be true: use of OEP, specifically networked participation and open pedagogy, can lead to OER awareness and use. Archer (2003) notes that structural/cultural properties have generative powers of constraint and enablement. Where openness is not "infused" at an institution (Veletsianos, 2015), as in this case, the absence of open education policy acts as a constraint to OER awareness and use. However, the nascent and growing use of OEP may lead individual educators to develop Personal Learning Networks (PLNs) through which they become aware of broader issues around openness, including OER.

Use of OEP by educators is complex, personal, contextual, and continually negotiated. The findings of this study highlight a number of key issues for higher education practitioners, researchers, managers, and policy makers. Open education promises much. But attention must be paid to the actual experiences and concerns of staff and students; empirical research should inform open education policy. In addition, a growing body of research advocates greater theorization and critical analysis of openness and open education (see Bell, 2016; Edwards, 2015; Gourlay, 2015; Knox, 2013; Watters, 2014). Recognition of the complexities and risks of openness, as well as the benefits - for individuals as well as institutions - should inform both policy and practice.

In their study of institutional culture and OER policy, Cox and Trotter (2016) found that appropriate institutional policies alone cannot ensure sustainable engagement with OER: "institutional culture mediates the role that policy plays in academics' decision making." The same appears to be true for OEP. Further research in this area would be useful; that is, studies of situated practices in specific places and times, enabling detailed exploration of agency, structure, and culture with respect to OEP. At a minimum, however, the findings of this study highlight the need for institutions to work broadly and collaboratively to build and support academic staff capacity in three key areas: developing digital literacies and digital capabilities; supporting individuals in navigating tensions between privacy and openness; and, critically, reflecting on the role of higher education and our roles as educators and researchers in an increasingly open and networked society.

The research study described here is limited in scope; it explores the experiences of a relatively small number of academic staff at one university. However, it extends and complements the literature, offering opportunities for further research and collaboration. This study comprised Phase 1 of my PhD research study on OEP in higher education. Two further phases are currently in process. Phase 2 is a survey of all academic staff at the same university and Phase 3 follows two open educators and their students in exploring how academic staff and students interact and negotiate their digital identities in open online spaces.

My thanks to each of the participants in this study: without your generosity, frankness, and support, this work would not have been possible. Many thanks to my PhD supervisor, Iain MacLaren, for feedback and support throughout the course of my research, and to my Graduate Research Committee: Simon Warren, Mary Fleming, Katheryn Cormican, and Kelly Coate. Finally, thanks to Frances Bell, Caroline Kuhn, and Leo Havemann for reviewing early versions of this paper, and to three anonymous reviewers from this journal for their insightful and useful feedback.

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2016). Opening the Textbook: Educational Resources in U.S. Higher Education, 2015-16. Babson Survey Research Group. Retrieved from http://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/openingthetextbook2016.pdf

Archer, M. S. (2003). Structure, agency, and the internal conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Armellini, A., & Nie, M. (2013). Open educational practices for curriculum enhancement. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 28(1), 7-20. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2013.796286

Atenas, J., Havemann, L., & Priego, E. (2014). Opening teaching landscapes: The importance of quality assurance in the delivery of open educational resources. Open Praxis, 6(1), 29-43. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.6.1.81

Becher, T., & Trowler, P. R. (2001). Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual enquiry and the cultures of discipline (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

Beetham, H., Falconer, I., McGill, L., & Littlejohn, A. (2012). Open practices: Briefing paper. JISC. Retrieved from https://oersynth.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/58444186/Open%20Practices%20briefing%20paper.pdf

Bell, F. (2016). (Dis)connected practice in heterotopic spaces for networked and connected learning. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Networked Learning 2016. Retrieved from http://www.networkedlearningconference.org.uk/abstracts/pdf/S3_Paper1.pdf

Biglan, A. (1973). Relationships between subject matter characteristics and the structure and output of university departments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57, 204-213. doi: 10.1037/h0034699

Casey, G., & Evans, T. (2011). Designing for learning: Online social networks as a classroom environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(7), 1-26. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v12i7.1011

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Conole, G., & Oliver, M. (Eds.). (2006). Contemporary perspectives in e-learning research: Themes, methods, and impact on practice. London: Routledge.

Couros, A., & Hildebrandt, K. (2016). Designing for open and social learning. In G. Veletsianos (Ed.), Emergence and innovation in digital learning: Foundations and applications. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press. doi: 10.15215/aupress/9781771991490.01

Cox, G. (2016). Explaining the relations between culture, structure and agency in lecturers' contribution and non-contribution to open educational resources in a higher education institution (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town, South Africa). Retrieved from https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/20300

Cox, G., & Trotter, H. (2016). Institutional culture and OER policy: How structure, culture, and agency mediate OER policy potential in South African universities. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(5). doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v17i5.2523

Czerniewicz, L., Deacon, A., Glover, M., & Walji, S. (2017). MOOC-making and open educational practices. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29 (Special Issue on Open Education), 81-97. doi: 10.1007/s12528-016-9128-7

DeRosa, R., & Robison, S. (2015). Pedagogy, technology, and the example of open educational resources. EDUCAUSE Review. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2015/11/pedagogy-technology-and-the-example-of-open-educational-resources

Deimann, M., & Sloep, P. (2013). How does open education work? In A. Meiszner, & L. Squires (Eds.), Openness and education (vol. 1, pp. 1-23). Emerald Group Publishing.

Edwards, R. (2015). Knowledge infrastructures and the inscrutability of openness in education. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(3), 251-264. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2015.1006131

Ehlers, U. -D. (2011). Extending the territory: From open educational resources to open educational practices. Journal of Open, Flexible and Distance Learning, 15(2). Retrieved from http://www.editlib.org/p/147891/

Geser, G. (2007). Open Educational Practices and Resources: OLCOS Roadmap, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.olcos.org/cms/upload/docs/olcos_roadmap.pdf

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. St. Louis, MO: Transaction Publishers.

Gourlay, L. (2015). Open education as a "heterotopia of desire." Learning, Media and Technology, 40(3), 1-18. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2015.1029941

Hallberg, L. R.-M. (2006). The "core category" of grounded theory: Making constant comparisons. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 1(3), 141-148. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v1i3.4927

Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology. Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/doc/276569994/Attributes-of-Open-Pedagogy-A-Model-for-Using-Open-Educational-Resources

Hodgkinson-Williams, C., & Gray, E. (2009). Degrees of openness: The emergence of OER at the University of Cape Town. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 5(5), 101-116. Retrieved from http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu/viewissue.php?id=23 - Refereed_Articles

Hogan, P., Carlson, B., & Kirk, C. (2015). Showcasing: Open educational practices' models using open educational resources. Open Education Global Conference, Banff Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Retrieved from http://conference.oeconsortium.org/2015/presentation/showcasing-open-educational-practices-models-using-open-educational-resources/

JISC. (2015). Developing students' digital literacy. Retrieved from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-students-digital-literacy

Karunanayaka, S. P., Naidu, S., Rajendra, J., & Ratnayake, H. (2015). From OER to OEP: Shifting practitioner perspectives and practices with innovative learning experience design. Open Praxis, 7(4), 339-350. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.7.4.252

Knox, J. (2013). The forum, the sardine can and the fake: Contesting, adapting and practicing the Massive Open Online Course. Selected Papers of Internet Research, 3(0). http://spir.aoir.org/index.php/spir/article/view/795

Lane, A. (2009). The impact of openness on bridging educational digital divides. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(5). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/637/1396

Lane, A., & McAndrew, P. (2010). Are open educational resources systematic or systemic change agents for teaching practice? British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(6), 952-962. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01119.x

Lather, P. (1991). Getting smart: Feminist research and pedagogy within/in the postmodern. New York: Routledge. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4316164

Lewis, C., Enciso, P. E., & Moje, E. B. (Eds.). (2007). Reframing Sociocultural Research on Literacy: Identity, Agency, and Power. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

Mackness, J. (2013). An alternative perspective on the meaning of "open" in higher education [Web log post]. https://jennymackness.wordpress.com/2013/04/17/an-alternative-perspective-on-the-meaning-of-open-in-higher-education/

Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2010). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114-133. doi: 10.1177/1461444810365313

Mavetera, N., & Kroeze, J. H. (2009). Practical considerations in grounded theory research. Sprouts: Working Papers on Information Systems, 9(32). https://dspace.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/3136/Mavetera_Kroeze_GroundedTheoryMethod.pdf?sequence=1

McLoughlin, C., & Lee, M. (2010). Personalised and self regulated learning in the Web 2.0 era: International exemplars of innovative pedagogy using social software. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(1). doi: 10.14742/ajet.1100

Moe, R. (2015). The brief and expansive history (and future) of the MOOC: Why two divergent models share the same name. Current Issues in Emerging eLearning, 2(1). http://scholarworks.umb.edu/ciee/vol2/iss1/2

Murphy, A. (2013). Open educational practices in higher education: Institutional adoption and challenges. Distance Education, 34(2), 201-217. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2013.793641

Nascimbeni, F., & Burgos, D. (2016). In search for the Open Educator: Proposal of a definition and a framework to increase openness adoption among university educators. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(6). doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v17i6.2736

National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Ireland. (2015). Learning resources and open access in higher education institutions in Ireland: Focused Research Report. Retrieved from http://www.teachingandlearning.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Project-1-LearningResourcesandOpenAccess-1607.pdf

Neylon, C. (2013). Open is a state of mind [Web log post]. http://cameronneylon.net/blog/open-is-a-state-of-mind/

OPAL (2011). Beyond OER: Shifting focus to open educational practices. OPAL Report 2011. Essen: Open Education Quality Initiative. https://www.scribd.com/document/49389350/OPALReport2011-Beyond-OER

Open Education Consortium. (n.d.). About the Open Education Consortium. Retrieved from http://www.oeconsortium.org/about-oec/

Peter, S., & Deimann, M. (2013). On the role of openness in education: A historical reconstruction. Open Praxis, 5(1), 7-14. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.5.1.23

Reed, P. (2013). Hashtags and retweets: Using Twitter to aid community, communication and casual (informal) learning. Research in Learning Technology, 21. doi: 10.3402/rlt.v21i0.19692

Rolfe, V. (2012). Open educational resources: Staff attitudes and awareness. Research in Learning Technology, 20. doi: 10.3402/rlt.v20i0/14395

Rosen, J. R., & Smale, M. A. (2015). Open Digital Pedagogy = Critical Pedagogy. Hybrid Pedagogy. http://www.digitalpedagogylab.com/hybridped/open-digital-pedagogy-critical-pedagogy/

Rowe, M., Bozalek, V., & Frantz, J. (2013). Using Google Drive to facilitate a blended approach to authentic learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4), 594-606. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12063

Schreurs, B., den Beemt, A. V., Prinsen, F., Witthaus, G., Conole, G., & de Laat, M. (2014). An investigation into social learning activities by practitioners in open educational practices. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(4). doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v15i4.1905

Siemens, G., & Matheos, K. (2010). Systemic changes in higher education. In Education, 16(1). Retrieved from http://ineducation.ca/index.php/ineducation/article/view/42

Smyth, R., Bossu, C., & Stagg, A. (2016). Toward an open empowered learning model of pedagogy in higher education. In S. Reushie, A. Antonio, & M. Keppell. (Eds.), Open learning and formal credentialing in higher education: Curriculum models and institutional policies (pp. 205-222). Hershey, PA: IGI Global. Retrieved from http://www.igi-global.com/book/open-learning-formal-credentialing-higher/129622

Stewart, B. (2015). Open to influence: What counts as academic influence in scholarly networked Twitter participation. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(3), 1-23. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2015.1015547

Stommel, J. (2014). Critical digital pedagogy: a definition. Hybrid Pedagogy. http://www.digitalpedagogylab.com/hybridped/critical-digital-pedagogy-definition/

Trowler, P., Saunders, M., & Bamber, V. (Eds.) (2012 ). Tribes and territories in the 21 st century: Rethinking the significance of disciplines in higher education. London: Routledge.

Veletsianos, G. (2010). A definition of emerging technologies for education. In G. Veletsianos (Ed.), Emerging technologies in distance education. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press. Retrieved from http://www.aupress.ca/index.php/books/120177

Veletsianos, G. (2013). Open practices and identity: Evidence from researchers and educators' social media participation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4), 639-651. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12052

Veletsianos, G. (2015). A case study of scholars' open and sharing practices. Open Praxis, 7(3), 199-209. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.7.3.206

Veletsianos, G., & Kimmons, R. (2012a). Networked participatory scholarship: Emergent techno-cultural pressures toward open and digital scholarship in online networks. Computers & Education, 58(2), 766-774. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.001

Veletsianos, G., & Kimmons, R. (2012b). Assumptions and challenges of open scholarship. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(4), 166-189. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v13i4.1313

Vitak, J. (2012). The impact of context collapse and privacy on social network site disclosures. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(4), 451-470. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2012.732140

Watters, A. (2014). From "open" to justice [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://hackeducation.com/2014/11/16/from-open-to-justice

Waycott, J., Sheard, J., Thompson, C., & Clerehan, R. (2013). Making students' work visible on the social web: A blessing or a curse? Computers & Education, 68, 86-95. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.04.026

Weller, M. (2011). The digital scholar: How technology is transforming scholarly practice. Basingstoke: Bloomsbury Academic.

Weller, M. (2014). The battle for open: How openness won and why it doesn't feel like victory. London: Ubiquity Press.

Wiley, D. (2009). Defining "open" [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/1123

Wiley, D. (2015). Reflections on open education and the path forward [Web log post]. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/4082

Wiley, D., Bliss, T. J., and McEwen, M. (2014). Open educational resources: A review of the literature. Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. NY: Springer.

Winn, J. (2012). Open education: From the freedom of things to the freedom of people. In H. Stevenson, L. Bell, & M. Neary (Eds.), Towards teaching in public: Reshaping the modern university. London: Continuum.

Openness and Praxis: Exploring the Use of Open Educational Practices in Higher Education by Catherine Cronin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.