Aras Bozkurt and Mujgan Bozkaya

Anadolu University, Turkey

Volume 16, Number 5

The aim of this mixed method study is to identify evaluation criteria for interactive e-books. To find answers for the research questions of the study, both quantitative and qualitative data were collected through a four-round Delphi study with a panel consisting of 30 experts. After that, a total of 20 interactive e-books were examined with heuristic inquiry methodology. In the final phase, the results of the Delphi technique and the heuristic inquiry results were integrated. As a result, four themes, 15 dimensions, and 37 criteria were developed for interactive e-books. Lastly, the results and their implications are discussed in this paper and suggestions for further research are presented.

Keywords: Interactive e-books, evaluation criteria, Delphi study, heuristic inquiry, open and distance learning (ODL)

Open and Distance Learning (ODL) strives to provide effective, efficient, engaging, and enduring learning opportunities which are dependent on improvements and developments in information and communication technologies (ICT). There have been attempts to employ ICT to eliminate the limitations that derive from physical and psychological distance among learners, learning sources, and learning environments. The influence of ICT resulted in online and digital solutions that increase interaction in the learning process. Beldarrain (2006) suggests that technology has played a critical role in changing the dynamics of each delivery option over the years, as well as the pedagogy in ODL. As new technologies emerged, instructional designers and educators had unique opportunities to foster interaction and collaboration among learners, thus creating a true learning community.

As a result of these developments, e-books and, following that, interactive e-books have gained a wide interest and have been used as a valuable and viable medium in both traditional education and ODL. By realizing the potential of digital books, institutions of higher education have begun to provide interactive e-books for learners to be able to deliver the information in a more effective and attractive way. According to Rothman (2006), for distance educators as well as traditional classroom educators, digital books would not only enhance student access to information, but would also help revolutionize the processes of reading, analyzing, and researching.

As a response to current developments in the e-book and interactive e-book landscape, interactive e-books are defined and their pros and cons are explained in this study. Following that, interactivity in interactive e-books is discussed and finally evaluation criteria of interactive e-books are explained based on a mixed method study in which Delphi technique and heuristic inquiry were used.

Interactive e-books are used for providing flexibility and presenting enriched content by means of hard and soft technologies. As an emerging technology, it is a necessity to define evaluation criteria of interactive e-books and contribute to relevant literature.

On this basis, the main purpose of this research is to develop an evaluation criteria checklist for interactive e-books. Within this perspective, research questions for this study are as follows:

Books are defined as “the first teaching machine” (McLuhan, 1964, p.174) and they are indispensable in the teaching/learning process (West, Turner, & Zhao, 2010). For centuries, books have been the catalyst of dissemination and transmission of knowledge. They paved the way of improvement, helped to evolve humankind and have evolved themselves. The year 1971 was a milestone for electronic books (e-books). Michael Stern Hart initiated the Project Gutenberg that year to encourage the creation and distribution of e-books (Hart, 2004) and created the first digital version of Declaration of Independence as the first e-book in history (Hart, 1992). Other developments such as the first digital-born hypertext fiction Afternoon in 1980, DOS-based e-books and the Runeberg Project in 1992, PDF 1.0 in 1993, E-ink Corporation in 1997, first handheld e-book reader in 1998, copyright/copyleft and Creative Commons in 2001, Kindle e-book reader by Amazon in 2007, and tablet PCs and smartphones at the beginning of the new millennium triggered the evolution and acceptance of digital books (Bozkurt, 2013; Bozkurt & Bozkaya, 2013a).

When comparing definitions, conventional books (c-books) can be defined as a set of written and printed sheets that include text and visuals. As a digital version of c-books, Rao (2003) defines e-books as text in digital form, a book converted into digital form, digital reading materials, a book in a computer file format, an electronic file of words and images displayed on a device screen intended for more than solely reading e-books, or an electronic file formatted for display on dedicated e-book readers.

In 2011, introduction of the next-generation digital book required a new definition: interactive e-books. In his TED Talk (Technology, Entertainment and Design), Matas (2011) introduced one of the first known interactive e-books, Our Choice, and promoted it as a next-generation digital book. Our Choice was a clear indicator of the future of digital books as the first full-length digital book that utilized various creative and innovative features. Some features of this interactive e-book are given in Table 1.

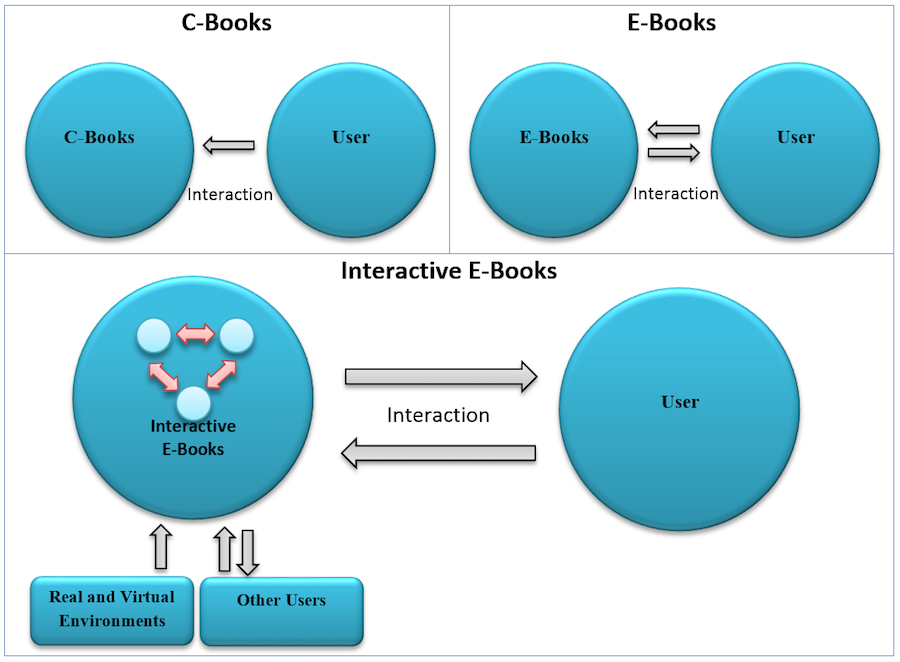

By examining 20 interactive e-books systematically, Bozkurt & Bozkaya (2013a; 2013b) defined interactive e-books as an improved extension of digital books. According to their definition, interactive e-books are essentially digital book formats in which the user, the digital book, and the environment can interact reciprocally at a high level; digital book elements can communicate and interact among themselves and environment as well as users, and many communication channels are put in use at one and the same time. They also defined the digital book as a generic term that covers e-books, interactive e-books, and other digital book formats. A comparison of c-books, e-books, and interactive e-books are provided in Figure 1.

|

|

Figure 1. Comparison of c-books, e-books and interactive e-books (Bozkurt & Bozkaya, 2013a; 2013b) . |

According to this definition, it is salient that advanced interactive e-books are at the forefront of the digital book evolution which is tightly connected to technological innovation. It can be also seen that as a result of e-books’ dependency on technology, the distinction between interactive e-books and software and mobile applications is being blurred. However, these blurring borders can become distinct by applying design principles of interactive e-books and determining the purpose of the application as it refers to the user’s electronic reading (e-reading) experience. In the e-reading experience with interactive e-books, there are four type of interactions: interaction between environments (real and virtual environments), interaction among the digital book elements, interaction with other users, and interaction with the user:

Interactive e-books have been preferred increasingly, especially from the beginning of 2000 onwards for the advantages they provide. Some of the advantages of interactive e-books are listed in Table 2.

In terms of users/readers:

In terms of authors:

In terms of libraries and other educational institutions:

In terms of publishers and retailers:

As well as having advantages, interactive e-books have some disadvantages. However, the following disadvantages in Table 3 mostly derive from external reasons, not from the inherent features of interactive e-books.

In terms of reading device:

In terms of piracy:

In terms of tactile experience:

Interaction, as a complex and multifaceted concept in all forms of education, fulfills many critical functions in the educational process (Anderson, 2003). It appears to be one of the most critical instructional elements (Kearsley, 1995) and it was highlighted that interaction is a necessary ingredient for a successful learning experience in ODL (McIsaac & Gunawardena, 1996). According to Dewey (1916), who used the word “transaction” instead of “interaction” to emphasize the relationship between organism and environment, interaction is the defining component of the educational process that occurs when the learners transform the inert information passed to them from another and construct it into knowledge with personal application and value. Moore and Kearsley (1996) focused on interaction in distance learning and described learner-content, learner-learner, and learner-instructor interaction, while Hillman, Willis, and Gunawardena (1994) additionally described learner-interface interaction. Moore and Kearsley (1996) further stated that effective teaching at a distance depends on a deep understanding of the nature of interaction and how to facilitate interaction through technologically transmitted communications. These ideas inspired instructional designers and educators not only to design interactivity in learning process, but also to design interactive learning tools such as interactive e-books.

Interaction design (IxD) and Human Computer Interaction (HCI) are terms that have been used interchangeably. Currently, there has been a growing interest in the structure and nature of interaction design in education and academia. Influenced heavily by ICT in education, interaction design became another discipline engaging in education, particularly in online and digital learning experiences.

According to Wagner (1994), within the ODL perspective, interaction is reciprocal events that require at least two objects and two actions, and it “occurs when these objects and events mutually influence one another” (p. 8). Silver (2007) defines interaction design as a blended endeavour of process, methodology, and attitude. Lowgren (2013) states that interaction design is about shaping digital things for individuals’ use.

In essence, interaction design is a system view. All the elements in an interactive system should be designed for a purpose (Bozkurt & Bozkaya, 2013a). That’s why interaction design uses five dimensions to have a broad view and cover all elements of an interactive system. On this basis, the first four dimensions of interaction design were introduced by Smith (2007) and the fifth dimension was added by Silver (2007).

According to Fischer and Coutellier (2005), there are three types of interaction: cognitive, sensorial, and pure physical interactions. It is important to define cognitive interaction since any type of books, including digital ones, are sources of information that require a cognitive interaction to process information and then construct knowledge. Interactive e-books in new generation mobile devices cover all these interactions. On this ground, in an interactive e-book design process, these three types of interaction should be designed in agreement with planned objectives. However, another important issue to decide upon is intended interaction level in interactive e-books.

The distinguishing feature to define and categorize book types (c-book, e-book or interactive e-book) is the level of interaction they exhibit. Interactive Multimedia Instruction (IMI), or as it is otherwise known, Interactive Courseware (ICW), has been developed over the years by the U.S Department of Defense (DoD) (1999). In the ICW model, there are four major levels of interactivity which are defined as the degree of student's involvement in the instructional activity. The four levels of interactivity identified by the ICW are provided in Table 4.

| Table 4. Interactivity levels and definitions | |

| Levels | Description |

|

Level 1: Passive. | The student acts solely as a receiver of information. |

| Level 2: Limited participation. | The student makes simple responses to instructional cues. |

|

Level 3: Complex participation. | The student makes a variety of responses using varied techniques in response to instructional cues. |

| Level 4: Real-time participation. | The student is directly involved in a life-like set of complex cues and responses. |

The current study attempts to examine a topic which has not been extensively researched as interactive e-books are a recent emerging technology. Among the few available studies, Wilson and Landoni (2002) prepared an electronic textbook design guideline which had been formed as a result of extensive evaluations of electronic books involving around 100 participants from the UK higher education. They developed 17 on-screen design guidelines and 5 hardware design guidelines. Wilson, Landoni, and Gibb (2002) further discussed the findings emerging from the EBONI (Electronic Books ON-screen Interface) Project. Diaz (2003) presented and explained a number of evaluation criteria for hypermedia educational e-books to help instructional designers and to provide guidance for addressing educational requirements during the design process of an e-book. The criteria presented were based on previous research and the author's experiences in the development of educational systems and projects. Crestani, Landoni, and Melucci (2006) incorporated the results of two separate studies into the design, development, and evaluation of e-books: The Visual Book and the Hyper-TextBook projects. The Visual Book project focused on the visual component of the book metaphor and The Hyper-TextBook concentrated on the importance of models and techniques for the automatic production of functional electronic versions of textbooks. The findings gathered in this study demonstrate similarities and confirm Wilson and Landoni’s (2002), Diaz’s (2003), and Crestani’s (2006) findings about evaluation criteria of e-books.

Previous research has generally focused on e-books which are usually in a single file format and include basic multimedia elements with low interaction. Therefore, it can be argued that there is a need to develop evaluation criteria for interactive e-books which include a combination of many multimedia components with high interactivity, and the current study intends to fill this gap.

Throughout this research, four theories were used to establish a sound base to start and provide a clear lens through which we can look, enhance our interpretation, generate valid ideas, and give meaning to the research findings. The theories applied in this research were the theories of Independent Study, Transactional Distance, Multimedia Richness, and Multimedia Learning.

Theory of Independent Study: According to Wedemeyer (1981), the essence of distance education is the independence of the learners. Wedemeyer’s Independent Study Theory emphasizes learner independence and adoption of technology as a way to implement that independence (Simonson et al., 2003). According to the theory, learning can occur in spite of the time-space barriers and learning should be individualized by providing wider choices to learners; learning responsibility belongs to learners themselves and they learn at their own paces.

Theory of Transactional Distance: This theory is originally an extension of the Theory of Independent Study. Inspired by Dewey’s term of transaction , the Transactional Distance Theory refers to the cognitive space between instructors and learners in an educational setting. Moore (2007) argues that transactional distance is a typology of all education programs having this distinguishing characteristic of separation of teacher and learner. According to Moore (1993), transactional distance is a psychological and communication space to be crossed, a space of potential misunderstanding between the inputs of instructor and those of the learner. The key concepts of the theory are dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy.

Theory of Media Richness : Developed originally by Daft and Lengel (1984), the Media Richness Theory is based on the contingency theory and the information processing theory. According to the theory, “the more equivocal a message, the more clues and data are needed to understand it, and media richness theory places communication mediums on a continuous scale that represents the richness of a medium and its ability to adequately communicate a complex message” (Carlson & Zmud, 1999, p. 155). The main idea of Media Richness Theory was expressed as "the more learning that can be pumped through a medium, the richer the medium” (Lengel & Daft, 1988, p. 226). According to the theory, the richness of the media is influenced by four criteria (Daft & Lengel, 1984): (1) Capacity for immediate feedback; (2) capacity to transmit multiple cues; (3) language variety; and (4) the capacity of the medium to have a personal focus.

Theory of Multimedia Learning: Proposed by Richard Mayer, this theory explains learning with multimedia from the perspectives of educational psychology and e-learning (Ataizi and Bozkurt, 2014) and claims that individuals learn better when multimedia messages are designed in ways that are consistent with how the human mind works (Clark & Mayer, 2011; Mayer, 2002). The theory has three main assumptions (Mayer, 2002): (1) there are two separate channels for processing information: the auditory and visual channels (Dual Coding Theory); (2) each channel has a limited capacity (cognitive load); and (3) learning is an active process of filtering, selecting, organizing, and integrating information through association with previous experiences.

The study was designed as an embedded mixed model research to provide a better understanding of the research problem. The purpose of the embedded design is to collect quantitative and qualitative data simultaneously or sequentially. In the embedded design, a secondary form of data is used to augment or provide additional sources of information not provided by the primary source of data (Creswell, 2004). Throughout this research, the Delphi technique (primary source of data) and heuristic inquiry method (secondary source of data) were applied to obtain and analyze data.

Because the topic was an emerging one dealing with different expertise areas such as instructional design and interaction design, and the number of the studies in the literature was insufficient, the Delphi technique was preferred as a primary source of data to be able to get expert opinions from different disciplines. The Delphi Method is based on a structured process for collecting and distilling knowledge from a group of experts by means of a series of questionnaires interspersed with controlled opinion feedback (Adler & Ziglio, 1996; Dalkey & Helmer, 1963; Koçdar & Aydın, 2013). As a highly flexible problem-solving process, it fits for situations where evidence based practice is dependent on expert opinion (Sandrey & Bulger, 2006). Expert panel members provide feedback, revise judgments, and contribute to the development of agreed-upon practices - all with complete anonymity (Flippo, 1998). Within this perspective, the basic assumption of the Delphi Method is that the informed, collective judgment of a group of experts is more accurate and reliable than individual judgment (Clayton, 1997; Ziglio, 1996). The key characteristics of the Delphi technique are defined as anonymity of respondents, controlled feedback process, and statistical response (Fowles, 1978).

User experience (UX) is the essence of the interaction design. Thus, in addition to theoretical and practical experiences of Delphi panelists, researchers employed heuristic inquiry to harness additional research findings which can be explored by directly engaging research questions. On this ground, heuristic inquiry was preferred as a secondary source of data. Heuristic inquiry is an experience-based technique for problem solving, learning, and discovery. Douglass and Moustakas (1985) define heuristic inquiry as a search for the discovery of meaning and essence in significant human experience. The heuristic inquiry is an adaptation of phenomenological inquiry, yet it requires the involvement of the researcher in a disciplined pursuit of research process (Hiles, 2001; Djuraskovic & Arthur, 2010).

The selection of panel members is considered to be critical for the Delphi process, which is directly related to the focus or objectives of the research (Sandrey & Bulger, 2006). Interactive e-books are a final product of different procedures and different expertise. Therefore, it is important to select experts for a purpose to apply their knowledge to a certain problem on the basis of criteria, which are developed from the nature of the problem under investigation (Hasson, Keeney, & McKenna, 2000).

For this research, the participants are required to be experts in one of the following areas: digital books, digital publishing, content design, instructional design, interface and layout design, or e-learning. It is further required that they have a background in academic research or experience working in the field. Through literature review and snowball sampling, 55 experts were invited to the research. A total of 30 experts expressed their intention of participating. A highly representative Delphi panel of 30 experts, from well-respected institutions and companies, who have published research and/or had practical and theoretical experience, was constructed to contribute to the validity and reliability of research findings.

In heuristic inquiry, as the secondary form of data, 20 distinguishing interactive e-books were selected. A set of criteria were defined to be able to examine representative samples that had interactive features peculiar to interactive e-books. The interactive e-books included in the heuristic research were those that were most downloaded, awarded, and had positive reviews by the critics. Book samples that exhibited different features in terms of the interaction level and genre were selected to have maximum variation sampling (Appendix A).

Before initiating Delphi rounds, a pilot study was carried out with three doctoral students. Delphi rounds were arranged based on their feedback. Between December 2012 and March 2013, a total of four online Delphi rounds were conducted. To be able to classify ideas hierarchically and navigate easily among the emerging criteria, terms are used as theme in macro level, dimension in meso level and criteria in micro level throughout the article.

In the heuristic inquiry, a total of 20 interactive e-books were downloaded into a tablet computer. The interactive e-books were selected purposefully from distinguished examples, most of which have notable awards and reviews (Appendix A). Each book was used and examined in four themes at the end of the Delphi study. First of all, the validity of the Delphi findings were checked by examining the applicability of the criteria which emerged in the Delphi rounds, using 20 interactive e-books. Following that, researchers systematically noted their experiences as well as the features observed. This process was conducted between March and May 2013. All the data gathered were coded, categorized, and put into themes using content analysis. The findings that matched with the findings gathered in the Delphi study were eliminated to assure that the same research findings were not replicated. It is salient that the four new criteria emerged from heuristic inquiry are mostly related with user experience which requires direct interaction with the products that are investigated. For that reason, it is believed that these four criteria didn’t emerge during the Delphi rounds. Lastly, four new criteria were defined and associated with relevant themes and dimensions. At the end of the Delphi and heuristic research processes, a total of four themes, 15 dimensions, and 37 criteria were identified.

In Delphi studies, qualitative data can be analyzed using content analysis techniques (Hasson, Keeney, & McKenna, 2000). The data in the first and second Delphi rounds of this study were analyzed using content analysis. The data were coded, categorized, and put into themes (see sample in Appendix B). The findings obtained were converted into short, simple sentences and presented as questionnaire items in the third and fourth Delphi rounds.

For the quantitative data in the third and fourth rounds, statistical methods were used. Consensus in a Delphi study is subject to interpretation. Consensus can be decided if a certain percentage falls within a prescribed range (Miller, 2006). Some researchers suggest that a level of at least 70 percent agreement is enough to call a consensus; on the other hand, there is no certain percentage defined and it changes according to the scope of the research topic. Other statistics used in Delphi studies are measures of central tendency (means, median, and mode) and level of dispersion (standard deviation and interquartile range) (Hasson, Keeney, & McKenna, 2000). To be able to get robust and reliable research results, a combination of different statistics were defined as the consensus level for the research. Percentage (80% for the third round and 90% for the fourth round), IQR, and median were used as statistical indicators of consensus (Table 5).

| Table 5. Measurement of consensus | |

| 3rd round | Median ≥ 4, IQR ≤ 1, Frequency 4-5 ≥ 80% |

| 4th round | Median ≥ 4, IQR ≤ 1, Frequency 4-5 ≥ 90% |

In the heuristic inquiry, both qualitative and quantitative data were gathered systematically through real life experiences. The data were then analyzed using content analysis. The findings were used to support and to check the Delphi study findings and to discover new findings concerning the evaluation criteria of interactive e-books.

The findings of this research is limited to current Web and mobile technologies in addition to capacities of mobile devices used in the research. For this reason, new themes, dimensions, and criteria can be added in time with the emergence of new technologies or new learning approaches.

The data in the first and second round of Delphi were coded by one of the authors (Rater A) of this study. Another author (Rater B) who was experienced in the field also rated the data of first and second rounds. Cohen’s Kappa (κ) was calculated to check the inter-rater reliability of the first two Delphi rounds. Inter-rater reliability between Raters A and B for the first round was κ =.918 (95% CI,.8551 to.9817), p <.0005 and κ =.951 (95% CI,.9040 to.9981), p <.0005 for the second round. Altman (1991) proposed that the extent of agreement can be qualified as poor (< 0.20), fair (0.21 to 0.40), moderate (0.41 to 0.60), good (0.61 to 0.80), and very good (0.81 to 1.00). Thus, the reliability of ratings for the first and second round Delphi data can be considered as very good.

The overall findings of this study are presented in Table 6. In the following table, research findings were organized as themes, dimensions and criteria. The criteria were associated with the most relevant dimensions and themes, but these criteria may intersect and overlap with other dimensions or themes.

| Table 6. Interactive e-book evaluation criteria |

| CONTENT |

| Presentation |

|

| Richness |

|

| Motivation and Attractiveness |

|

| Assessment and Evaluation |

|

| Integrity , Coherence and Connectivity |

|

| INTERFACE |

| Ease of Interface Use |

|

| Customization and Autonomy |

|

| Interface Design, Esthetic and Consistency |

|

| Universal Design for Accessibility |

|

| Support Services |

|

| Layout Frame Design |

|

| INTERACTIVITY |

| Interaction Richness |

|

| Digital book, environment and content interaction |

|

| TECHNOLOGY |

| Technical features |

|

| Copyright |

|

| *Interactive e-book evaluation criteria which were added after heuristic inquiry |

McLuhan’s (1964) widely known phrase, “The medium is the message,” means that the content of a mediated message is secondary to the medium (West et al., 2010). McLuhan did not ignore the importance of the content, but he deliberately pointed out the ability of the medium that shapes the message. In this study, the medium’s ability, that is to say interactive e-books, to shape the message became apparent in four basic themes that emerged as a result of the data analysis: content, interface, interaction, and technology.

Comparing the results of the current study with Wilson and Landoni (2002) and Diaz (2003), in addition to content and interface themes previously defined, two additional themes appeared: interaction and technology. E-books which were examined by Wilson and Landoni (2002) and Diaz (2003) used mobile devices and dedicated e-book readers as a display tool. However, new devices such as smartphones, tablet computers, and new generation dedicated e-book readers promise adaptive interaction which employs hard and soft technologies for an immersive user experience. These two themes emerged because interaction and technology are a result of fast developments in soft and especially hard technologies. Interactive e-books use hardware in an innovative way by employing their native features to increase depth of interaction both physically and cognitively. The increasing capacities of hard and soft technologies projected themselves as new themes in the digital book field. In other words, interactive e-books promise more than reading experience; they promise e-reading experience which includes cognitive, sensorial, and physical interactions.

It is also seen that the interactive e-book criteria that emerged in this research are coherent with basic principles of four theories which indicate interactive e-books’ value for ODL:

In this study, through a mixed research design in which Delphi technique and heuristic inquiry were used to gather data, four themes, 15 dimensions, and 37 criteria were developed to be able to evaluate interactive e-books. As a significant learning material, this study revealed important aspects of interactive e-books to ease access to information and to increase interaction, which are needed for meaningful learning experiences for distant learners.

In this study, a set of criteria was proposed to evaluate interactive e-books. Interactive e-books as a learning material encompasses many facets such as interaction design, instructional design, and interface design. Furthermore, hardware and software capabilities are directly related with the proposed evaluation criteria. Thus, the criteria revealed in this research can be developed according to changing needs of learners, and new hard and soft technologies. It is believed that the findings gathered in this research will:

As a result of the Delphi study, heuristic design and literature review, the following implications can be taken into consideration for future research:

As a final remark, this study does not claim that interactive e-books are superior to c-books or e-books; conversely, it claims that interactive e-books are a good and flexible alternative to be able to provide individualized learning opportunities. On this basis, the themes, dimensions, and criteria can be used as a checklist to identify strengths and weaknesses of interactive e-books and can be helpful to guide researchers who are interested in interactive e-books as a learning material. It is believed that well designed interactive e-books can significantly contribute to learning process in an effective and efficient way.

This study was supported by Anadolu University Scientific Research Projects Commission under the grant no: 1303E040.

This study is the reviewed and improved version of the thesis “Defining Evaluation Criteria for Interactive E-Books for Open and Distance Learning”, completed in the Distance Education Department of Social Sciences Institute at Anadolu University in 2013.

Adler, M., & Ziglio, E. (1996). Gazing into the oracle. Jessica Kingsley Publishers: Bristol, PA.

Altman, D. G. (1991). Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London: Chapman & Hall.

Anderson, T. (2003). Modes of interaction in distance education: Recent developments and research questions. In M. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of Distance Education (p. 129-144). Mahwah, NJ.: Erlbaum.

Ataizi, M. & Bozkurt, A. (2014). Book Review: E-Learning and the Science of Instruction. Contemporary Educational Technology, 5 (2), 175-178.

Beldarrain, Y. (2006). Distance education trends: Integrating new technologies to foster student interaction and collaboration. Distance education, 27 (2), 139-153.

Bozkurt, A., & Bozkaya, M. (2013a). Etkileşimli e-kitap Değerlendirme Kriterleri. Eskişehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi Yayınları. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/6007097/Etkileşimli_e-kitap_Değerlendirme_Kriterleri

Bozkurt, A., & Bozkaya, M. (2013b). Etkileşimli E-Kitap: Dünü, Bugünü ve Yarını. Akademik Bilişim 2013. (s.375-381). Akdeniz Üniversitesi, 23-25 Ocak, Antalya. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/2536903/Etkilesimli_E-Kitap_Dunu_Bugunu_ve_Yarini

Bozkurt, A. (2013). Açık ve Uzaktan Öğrenmeye Yönelik Etkileşimli E-kitap Değerlendirme Kriterlerinin Belirlenmesi. Anadolu Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Uzaktan Eğitim Anabilim Dalı. Yüksek Lisans Tezi. Eskişehir. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/3802974/Acik_ve_Uzaktan_Ogrenmeye_Yonelik_Etkilesimli_E-kitap_Degerlendirme_Kriterlerinin_Belirlenmesi

Carlson, J., & Zmud, R. (1999). Channel expansion theory and the experiential nature of media richness perceptions. Academy of Management Journal, 42 (2), 153-170.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2011). E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. John Wiley & Sons.

Clayton, M. J. (1997). Delphi: a technique to harness expert opinion for critical decision‐making tasks in education. Educational Psychology , 17 (4), 373-386.

Crestani, F., Landoni, M., & Melucci, M. (2006). Appearance and functionality of electronic books. International Journal on Digital Libraries , 6 (2), 192-209.

Creswell, J. W. (2004). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Pearson.

Daft, R.L. & Lengel, R.H. (1984). Information richness: a new approach to managerial behavior and organizational design. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (p. 191-233). Homewood, IL: JAI Press.

Dalkey, N., & Helmer, O. (1963). Delphi technique: characteristics and sequence model to the use of experts. Manag Sci , 9 , 458-67.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan.

Díaz, P. (2003). Usability of hypermedia educational e-books. D-Lib magazine , 9 (3). Retrieved from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/march03/diaz/03diaz.html

Djuraskovic, I., & Arthur, N. (2010). Heuristic Inquiry: A Personal Journey of Acculturation and Identity Reconstruction. Qualitative Report , 15 (6), 1569-1593.

DoD, (1999). Department of Defense Handbook: Development of Interactive Multimedia Instruction (IMI). Retrieved from http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/dod/hbk3.pdf

Douglass, B. G., & Moustakas, C. (1985). Heuristic Inquiry: The Internal Search to Know. Journal of Humanistic Psychology , 25 (3), 39-55.

Fischer, X., & Coutellier, D. (2006). Research in Interactive Design: Proceedings of Virtual Concept 2005. Springer.

Flippo, R. F. (1998). Points of agreement: A display of professional unity in our field. The Reading Teacher , 30-40.

Fowles, J., (1978). Handbook of futures research. Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Hart, M. (1992). The History and Philosophy of Project Gutenberg by Michael Hart. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Gutenberg:The_History_and_Philosophy_of_Project_Gutenberg_by_Michael_Hart

Hart, M. (2004). Gutenberg Mission Statement by Michael Hart. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Gutenberg:Project_Gutenberg_Mission_Statement_by_Michael_Hart

Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 32 (4), 1008-1015.

Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 32 (4), 1008-1015.

Hiles, D. (2001). Heuristic inquiry and transpersonal research. Paper presented to CCPE, October 2001, London.

Hillman, D. C., Willis, D. J., & Gunawardena, C. N. (1994). Learner-interface interaction in distance education: An extension of contemporary models and strategies for parishioners. The American Journal of Distance Education, 8 (2), 30-42.

Kearsley, G. (1995). The nature and value of interaction in distance learning. Paper presented at the Distance Education Symposium 3: Interaction, University Park, Pennsylvania State University.

Koçdar, S. & Aydın, C. H., (2013). Açık ve Uzaktan Öğrenme Araştırmalarında Delfi Tekniğinin Kullanımı. Anadolu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. 13 (3), 31-44.

Lengel, R. H., & Daft, R. L. (1988). The selection of communication media as an executive skill. The Academy of Management Executive , 2 (3), 225-232.

Lowgren, J. (2013). Interaction Design - brief intro. In M. Soegaard & R. F. Dam (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction, 2nd Ed. Aarhus, Denmark: The Interaction Design Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.interaction-design.org/encyclopedia/interaction_design.html

Matas, M. (2011). A next-generation digital book. TED: Talks in less than six minutes. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/mike_matas.html

Mayer, R. E. (2002). Multimedia learning. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 41 , 85-139.

McIsaac, M. S., & Gunawardena, C. N. (1996). Distance education. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology: A project of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 403–437). New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media. New York: Mentor.

Miller, L. E. (2006, October). Determining what could/should be: The Delphi technique and its application. Paper presented at the meeting of the 2006 annual meeting of the Mid-Western Educational Research Association, Columbus, Ohio.

Moore, M. G. (1993). Theory of transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical Principles of Distance Education (pp. 22-29). New York: Routledge

Moore, M. G. (2007). The theory of transactional distance. In M.Moore (Ed.), Handbook of distance education (pp. 66-85). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Moore, M. G., & Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance education: A systems view. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Rao, S. S. (2003). Electronic books: A review and evaluation. Library Hi Tech, 21 (1), 85-93.

Rothman, D. (2006). E-books: Why they matter for distance education and how they could get much better. Innovate: Journal of Online Education, 2 (6).

Sandrey, M. A., & Bulger, S. M. (2006). The Delphi Method: An approach for facilitating evidence based practice in athletic training. Dissertation Abstracts (General) , 1979 , 334.

Silver, K. (2007). What Puts the Design in Interaction Design. UX Matters. Retrieved from http://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2007/07/what-puts-the-design-in-interaction-design.php

Simonson, M., Smaldino, S., Albright, M., & Zvacek, S. (2011). Teaching and Learning at a Distance: Foundations of Distance Education (5th Edition). Pearson Education.

Smith, G. C. (2007). Foreword. In B. Moggridge & B. Atkinson (Eds.), Designing Interactions (Vol. 17). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wagner, E. D. (1994). In support of a functional definition of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 8 (2), 6–26.

Wedemeyer, C. (1981). Learning at the backdoor. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

West, R. L., Turner, L. H., & Zhao, G. (2010). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Wilson, R., & Landoni, M. (2002). EBONI: Electronic textbook design guidelines. JISC. Retrieved from http://ebooks.strath.ac.uk/eboni/guidelines/

Wilson, R., Landoni, M., & Gibb, F. (2002). Guidelines for designing electronic books. In Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries (pp. 47-60). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

Ziglio, E. (1996). The Delphi method and its contribution to decision-making. Gazing into the oracle: The Delphi method and its application to social policy and public health , 3-33.

List of interactive e-books examined in heuristic inquiry

Example of content analysis and procedure for coding and categorizing according to themes, dimensions and criteria

© Bozkurt and Bozkaya