|

Bonnie E Stewart

University of Prince Edward Island, Canada

In an era of knowledge abundance, scholars have the capacity to distribute and share ideas and artifacts via digital networks, yet networked scholarship often remains unrecognized within institutional spheres of influence. Using ethnographic methods including participant observation, interviews, and document analysis, this study investigates networks as sites of scholarship. Its purpose is to situate networked practices within Boyer’s (1990) four components of scholarship – discovery, integration, application, and teaching – and to explore them as a techno-cultural system of scholarship suited to an era of knowledge abundance. Not only does the paper find that networked engagement both aligns with and exceeds Boyer’s model for scholarship, it suggests that networked scholarship may enact Boyer’s initial aim of broadening scholarship itself through fostering extensive cross-disciplinary, public ties and rewarding connection, collaboration, and curation between individuals rather than roles or institutions.

Keywords: Networked scholarship; digital scholarship; participatory culture; knowledge abundance; Boyer’s model of scholarship

Scholarly use of online networks and social media is growing (Seaman & Tinti-Kane, 2013; VanNoorden, 2014), enabling new means of scholarly connection, communication, and collaboration. Yet ideas of scholarship often remain based in models that privilege peer review and the scholarly publishing systems that surround it (Weller, 2011). As Harley, Acord, Earl-Novell, Lawrence, and King (2010) assert, “Experiments in new genres of scholarship and dissemination are occurring in every field, but they are taking place within the context of relatively conservative value and reward systems that have the practice of peer review at their core” (p. 13). Thus, even though social media presence has been shown to increase visibility and citations (Terras, 2012; Mewburn & Thompson, 2013), and networked practices help establish reputation and connections with more-established faculty (Hurt & Yin, 2006), digital practices tend to remain on the margins of the tenure and promotions systems by which academia defines itself (Ellison & Eatman, 2008; Gruzd, Staves, & Wilk, 2011). This paper, however, demonstrates how networked scholarly practices align with and even exceed Boyer’s (1990) exemplar for scholarship.

The paper outlines an ethnographic investigation of scholarship in digital participatory networks, particularly on Twitter. Drawing on Veletsianos and Kimmons’ (2012) concept of Networked Participatory Scholarship (NPS) and their assertion that “[s]cholars are part of a complex techno-cultural system that is ever changing in response to both internal and external stimuli, including technological innovations and dominant cultural values” (p. 773), the study examined the techno-cultural practices of NPS. In the paper, I trace the practices and perspectives of networked scholars from a variety of locales and institutional status positions, in order to suggest that NPS constitutes an emergent techno-cultural scholarly system of its own, separate from – though intersecting with – that of contemporary mainstream academia.

Boyer’s (1990) empirical study of scholarly practices asserts that knowledge is generated by formal research, but also “through synthesis, through practice, and through teaching” (Boyer, 1990, p. 25). His typology seeks to place these four on equal footing in order to create a more inclusive scholarship. Pearce, Weller, Scanlon and Kinsley (2010) have drawn deeply from Boyer’s framework in examining the implications of digital scholarship for academia, and Veletsianos and Kimmons (2012) ground NPS’ definition of scholarship in Boyer’s model. However, the specific practices of individual networked scholars – and the techno-cultural system they enact – have yet to be assessed and analyzed through the lens of Boyer’s vision for the profession. The key gap in knowledge that this paper aims to address is the alignment of NPS practices with Boyer’s framework for scholarship. The paper’s key contribution is to situate this new techno-cultural system as scholarship of and for a context of knowledge abundance.

Prior to the digital era, scholarly knowledge was traditionally organized around the premise that knowledge is scarce and its artifacts materially vulnerable. Eye’s (1974) seminal article on knowledge abundance asserts, “[M]aterial can be transformed from one state to another but the original state is diminished…materials are exhaustible” (p. 445). Manuscripts and books as knowledge artifacts are exhaustible, and costly to produce and distribute. Digital content, however, is persistent, replicable, scalable and searchable (boyd, 2011, p. 46); digital knowledge artifacts can be distributed with negligible cost to originator or user, and without being consumed or diminished in the process. Thus widespread and increasingly mobile access to digital knowledge artifacts in “an abundant and continually changing world of information” (Jenkins, 2006, Networking section, para. 1) marks a shift from an era of knowledge scarcity to an era of knowledge abundance, even though access remains inequitably distributed.

Yet the practices of scarcity do not simply dissipate in the face of abundance. While the research and teaching functions of the university have to some extent incorporated digital knowledge artifacts, many aspects of the techno-cultural system of the contemporary academy remain rooted in the premise of scarcity, or the hierarchies scarcity has fostered. Cope and Kalantzis (2009) frame this fact as a pivotal flaw and breaking point in contemporary knowledge production. Daniels (2013) asserts the persistence and prestige of the scarcity-based ideal of scholarship; “We have our own “legacy” model of academic scholarship with distinct characteristics…analog, closed, removed from the public sphere, and monastic” (Legacy academic scholarship section, para. 3). Weller (2011) frames lecture as a “‘pedagogy of scarcity’…based around a one to many model to make the best use of the scarce resource (the expert)” (p. 226). In peer review and impact analysis, academic publishing retains the false residue of scarcity for the profit of journal monopolies like Elsevier, Springer, and Wiley. Digital technologies make it possible to peer review and distribute scholarly artifacts largely without cost, but practices and prestige are slower to change. As de Zepetnek and Jia (2014) note, “Many senior and tenured scholars tend to treat open-access publication as complements rather than substitutes to the publication of their work in print journals” (p. 2). This collective residue of scarcity permeates the techno-cultural system of institutional scholarship.

Yet as prices for top journals soar increasingly out of the reach of smaller institutions (Willinsky, 2006; Schmitt, 2014) and the prestige and security of the tenure reward system grows rarified (Clawson, 2009; Munro, 2015), academia’s attachment to scarcity begins to appear unsustainable. This research-based ethnographic portrait of NPS practices aims to illustrate an alternative scholarship of abundance.

This study explored the participatory culture of networked scholarship and the meanings constructed and circulated within it, using participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and document analysis as its primary methods. Ethnography emphasizes detailed, situated accounts and the “valuable knowledge of participants as meaning-making actors” (Boellstorff, Nardi, Pearce & Taylor, 2012, p. 19-20). Geertz’s (1973) foundational ethnography characterizes cultural practices as “suspended in webs of significance” (p. 2); this exploration of NPS as a techno-cultural system emphasizes the webs of significance and meaning experienced and enacted within the system being investigated.

The study approached scholarship as a sociomaterial phenomenon (Law, 2009) in which technological infrastructures, differential identity markers, and norms of practice and prestige all combine to form distinct if overlapping techno-cultural systems.

The study sought networked scholars from a wide range of geopolitical and identity locations within the English-speaking academic world. The call for participants was blogged and tweeted; the link was shared and re-tweeted over 150 times, resulting in 33 responses. Criteria for inclusion required active institutional affiliation as a scholar, active use of Twitter within scholarly networks for at least two years (based in White & LeCornu’s (2011) visitors and residents model for online participation), and active sharing of scholarly work and ideas in networks (based in Bruns’ (2007) concept of produsage, or shared production and consumption within networks).

Using these criteria, 14 participants were selected for maximum diversity of location and identity markers. 13 remained active throughout the study. Participants came from Canada, the US, Mexico, Australia, Singapore, Ireland, Italy, and South Africa. 10 were female; four male. Six identified with an ethnic heritage in some way marked or non-dominant in their location; four identified as gay or queer. Seven were Ph.D students or candidates at various stages of completion; two of these held longstanding administrative or teaching positions in their institutions. Three participants were early career scholars, one on tenure-track; three were senior professors or researchers. They ranged in age from twenties through fifties, and in Twitter followers from a few hundred through 15,000. All participants chose to be openly identified in the research by their public Twitter handles.

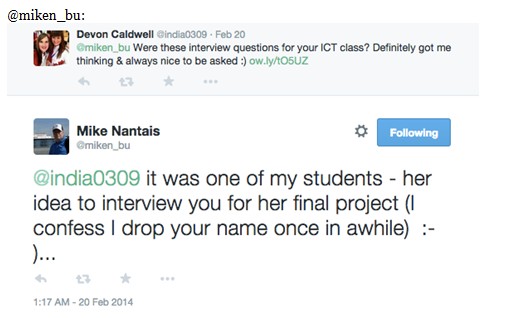

Participant observation was conducted from November 2013 through February 2014, using Twitter as the central site of observation. Participant blogs, Facebook and Instagram accounts, and other platforms that participants deemed relevant to their scholarship were also observed. A Twitter account created specifically for the study was used both as a lens for observation and engagement, and as a platform to share notes regarding emergent patterns. The researcher also kept extensive offline ethnographic notes throughout the observation period, and utilized Twitter’s “favorites” feature daily to mark participant tweets.

All participants were asked to choose a representative 24-hour period during which their networked engagement would be examined in-depth; they notified the researcher shortly after their chosen time frame to enable her to trace back through their interactions to gain contextual perspective. They then submitted short reflective documents with screen captures of their interactions, outlining their perspectives and understandings of their engagement; these understandings were analyzed against the data from participant observation to verify and contextualize interactions. 11 participants submitted this document.

Participants were sent documents consisting of two questions about their perceptions of engagement norms and power relations on Twitter, and screen captures of the Twitter profiles of five networked scholars who had volunteered to have their identities used as exemplars. Participants were asked to comment on their perceptions of the exemplars’ influence and potential value to their networks. 12 of 14 participants completed and submitted this assessment.

10 participants were interviewed via Skype, and one follow-up interview was conducted some months later. Interviews were semi-structured and recorded. Questions focused on participants’ practices, experiences, and perceptions of networked scholarship. Conversations were emergent and individuated based on the 24-hour reflections.

Unfocused transcription technique was used to transcribe the interviews, “without attempting to represent…detailed contextual or interactional characteristics” (Gibson & Brown, 2009, p. 116). Transcripts were collated with the written data participants had submitted, creating 13 separate participant documents. In some cases, relevant participant blog posts were included in these documents as well. Key emergent themes in the documents were identified and hand-coded to try to trace commonalities, distinctions, and relationships. The data was re-read against themes, codes, and subcodes using open coding and a form of axial coding.

When participant documents were themed and coded, they were sent back to participants for approval or further input. The study was designed to respect the participatory tenets of NPS, in which rigor was framed as an overt commitment to accountability, credibility and confirmability to participants and to the study’s epistemological and ethical tenets (Guba & Lincoln, 2005). In qualitative research, primary goals include believability, based on coherence, insight, and instrumental utility (Eisner, 1991), and trustworthiness (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), achieved through a process of verification rather than through quantitative validity measures. As part of the verification process, themes, coded transcripts, and findings were shared with participants, and input, clarification, and critique were invited. Six participants extended or altered their reflections based on this invitation. Aspects of the study were blogged, as well, and four participants commented on these posts and added their perspectives to the public record. Throughout the research process, participants’ confirmation of general conclusions and of statements attributed to them was sought and attained before publication processes were initiated.

To situate NPS practices as a distinct techno-cultural system of scholarship predicated in abundance, participant documents were first analyzed against the four central elements identified in Boyer’s (1990) framework for scholarship, then examined to determine what was not encompassed. While scholars’ practices diverged, and distinctions as well as commonalities are represented within the space available here, the webs of significance that emerged show both overlaps and key distinctions between the techno-cultural systems of NPS and the academic status quo. These patterns emerged in spite of the fact that study participants were all situated within both systems, and came from varying academic status positions and geopolitical locations.

The scholarship of discovery is the core academic work of building new knowledge through research and investigation (Boyer, 1990). Throughout the course of the study, networked scholars used Twitter and their broader networks to invite and enact contributions to knowledge, through conversations and informal polls as well as through more formal means such as invitations to participate in surveys or other research activities. Participants were actively engaged in informed and intellectually robust public exchanges as well as – in many cases – playful and personal repartee. Twitter served as a space for thinking aloud, sharing expertise, and raising investigative conversations. Participants appeared to carve out regular areas of discussion and investigation for which they become known, in their Twitter circles; peers would then send them links on those topics due to their expressed interests, and signal them into conversations in those areas, thereby extending participants’ network reach and visibility. A majority of participants reported that this circulation of ideas and resources not only helped them build new knowledge and become aware of new literature in their fields, but also broadened their understanding of alternate viewpoints in their areas of expertise. Twitter was a site of learning and public scholarly contribution.

Scholarship of discovery – in the literal sense of discovering new and relevant resources and perspectives that influence research and academic production – was part of all participants’ NPS practices, no matter their discipline or area of study.

@exhaust_fumes: (field: early modern literature) “I joined because people in my field were on Twitter and I realized there were library fellowships and I wasn’t tapped into that – there’s a whole world of academic funding that I never knew about. Twitter has been a way of being connected to opportunities.”

@socworkpodcast: (field: social work) “When G+ came out, I created a social work and technology community. I sent out a tweet; in a week we had a hundred people…it was this vibrant and engaging exchange of ideas. Those of us on Twitter who’d been confined to 140 characters were able to interact more in longform, and out of that community grew multiple scholarly academic products. There have been four articles published, and I organized a thinktank on the use of social media in social work education.”

The sharing of research-based knowledge is key to scholarship as a techno-cultural system, whether in NPS or institutional spheres. The distinction is in how and how often scholarship is shared, at what point scholarship is shared, and by whom. In addition to tweeting directly on topics of research and investigation, all participants in the study shared at least one blog post, report, slide deck, podcast or formal publication of their own via Twitter during the three-month course of observation. Two shared over 25 artifacts in the same time frame. The majority of this work was iterative rather than summative, and focused on giving a partial, situated picture of work processes or content as well as conclusions. This type of sharing circulated widely among participants’ networks, particularly when topics related broadly to digital technologies, higher education, or other fast-changing sites of scholarship and conversation.

The majority of participants also circulated others’ scholarly work on an almost-daily basis. Most stated that they shared content they felt would be of interest to their audiences or would align with the areas of expertise and identity that they had cultivated via networks. This intersection of content and identity is not new to the “reputational economy” (Willinsky, 2010) of academia, but in NPS, the content that counts towards academic identity and influence extends beyond scholars’ own work. Networked scholars become known for what they share, even if the bulk of that content originates with others. This creates a milieu in which scholarly artifacts have value and are extensively curated and circulated, not only for their content but for their capacity to facilitate network ties among scholars with shared interests. In such a milieu, a robust network can be a professional asset in hiring contexts (Becker, 2015), signifying a scholar’s capacity to bring visibility, influence, and access to wide-ranging scholarly ties to an institution, association or conference.

In the process of using, sharing, and contributing to this abundant and ever-renewing body of resources and ideas, scholars become more visible to each other and their areas of interest more legible (Stewart, 2015). Central to this visibility are forms of citation that have emerged as common practice in networks, but have ties to traditional scholarship of discovery. The user-built growth of the internet drew extensively from the academic model of knowledge-sharing, and the Google search engine was designed on the same principles as academic citation (Brin & Page, 1998). Although Twitter limits expression to 140 characters, study participants often referenced both the author(s) of a resource they were sharing and the person through whom they discovered that resource.

Thus networked scholarship of discovery, as a techno-cultural system, shares surface commonalities with the citation practices that mark conventional scholarly dissemination, but both the technical and the cultural aspects of the process are organized differently. While scholarly publishers and institutions have traditionally absorbed the costs of production and dissemination of scholarly artifacts, instituting gatekeeping hierarchies in the process, the digital capacity for replication and distribution minimizes that material cost. This opens up spaces where production and dissemination can be engaged in by individuals regardless of institutional ties, so long as they build the networks necessary to foster exchange. The digital knowledge artifacts that circulate in these networks tend to be more varied and often more iterative than those that have gone through the conventional gatekeeping process, not only because the gatekeeping is bypassed but because digital artifacts need not be finalized as print artifacts must be, but can be continually updated as ideas emerge. Thus, while networked scholarship of discovery still circulates traditional markers of scholarly quality, such as highly-ranked journals or elite brand institutions, it particularly values and rewards iterative, exploratory work and the capacity to assess and curate value from the midst of knowledge abundance. Moreover, it fosters a techno-cultural scholarly system structured primarily around individual connections, rather than institutions.

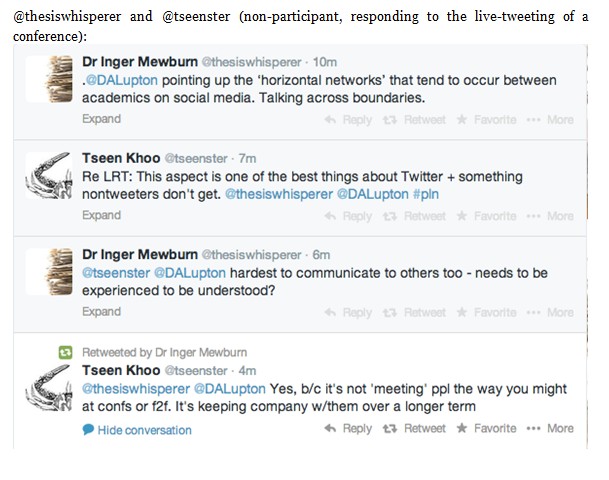

In the process of abundant sharing that marks NPS, the boundaries around disciplines become blurred. In Boyer’s (1990) framework, scholarship of integration involves “making connections across the disciplines, placing the specialties in larger context, illumining data in a revealing way, often educating nonspecialists too…serious disciplined work that seeks to interpret, draw together, and bring new insight to bear on original research” (p. 17-18). The way Twitter draws scholars from multiple disciplines and geographic areas together via conversations and hashtags emerged as a clear manifestation of scholarship of integration. Participants demonstrated active engagement with multiple audiences, across fields and disciplines. The accounts that participants connected with in their 24-hour reflections were traced, and in all cases but one participants were found to engage across both geographic and disciplinary boundaries.

@antoesp: “Twitter is an opportunity to receive more diversified feedback and have a chance to understand how the approach to solutions changes according to different academic cultures.”

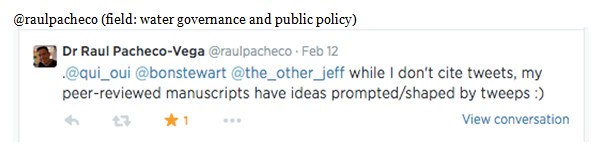

@raulpacheco: “I find when I have conversations on academic Twitter my brain starts absorbing information on data and learning, new ways of looking at things…Twitter conversations keep pushing my thinking, I’m able to trace what’s going on and react more quickly. I follow across disciplines: geographers, anthropology, sociology, poli sci, people in higher ed, and technologies.”

Boyer (1990) emphasizes scholarship of integration as “research at the boundaries where fields converge…[T]hose engaged in integration ask “What do the findings mean?” (p. 18). Thus scholarship of integration centers on public discussions and negotiations of meaning; what distinguishes the techno-cultural system of NPS is that this happens in constant, abundant real-time. This indirectly reinforces the system’s emphasis on individual rather than institution; the regular unsettling of the boundaries of what is known or understood makes formal hierarchies and categories – tenets of the techno-cultural system of institutional, disciplinary scholarship – difficult to enact and enforce. In NPS, belonging is de-institutionalized to the extent that individuals without visible institutional connections can nonetheless hold positions of status within primarily-academic Twitter spheres, based on long-term engagement. While power relations in networks demand ongoing investigation, networked participation nonetheless minimizes institutional gatekeeping around scholars’ engagement, enabling more horizontal and hybrid connections and fostering scholarship of integration. Since participants in the study were situated in both networks and institutions, they were able to speak to distinctions between the two systems on these fronts.

@catherinecronin: “I’m reminded of Mary Catherine Bateson’s Composing a Life. Bateson chronicled the careers of several successful women, most of whom had multiple and varied careers. Bateson noted how this differed from the stereotypical (predominantly male) notion of a career, where you step forward, ever higher up the career ladder. Bateson observed that these successful women’s careers involved moving and connecting across many different spheres. I relate to that. I’ve always been fine with the fact that the university didn’t know all of the work that I did. But being involved in networks means I can speak to all my roles, there are fewer boundaries.”

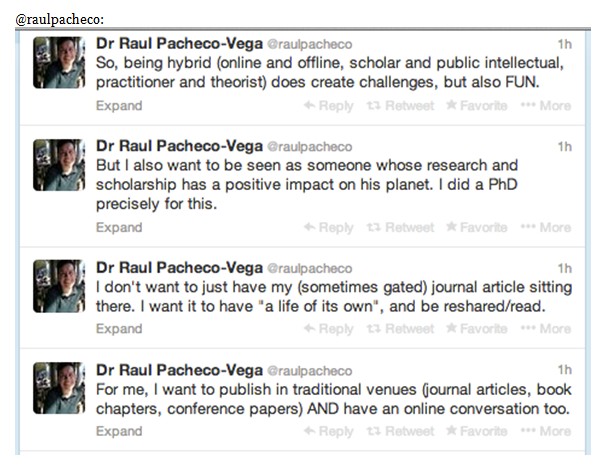

NPS’ emphasis on multiplicity of audience extends beyond academic audiences to public audiences, aligning with Boyer’s definition of scholarship of application. Boyer (1990) asserts, “…To be considered scholarship, service activities must be tied directly to one’s special field of knowledge and relate to, and flow directly out of, this professional activity” (p. 22). While not all Twitter engagement is tied to scholars’ areas of expertise, all participants in my study engaged in discussions related to their scholarly identities and knowledge at least on a weekly basis. A number referred their NPS practices as a form of knowledge translation or public intellectual engagement, and were explicit about actively managing the breadth of audiences afforded by networked scholarship.

@wishcrys (reflecting on how she shares her work): “I chose to make the blogpost live on a Friday evening, the busiest peak hour all week for my fieldsite ensuring the highest viewer traffic… A couple of days later, I plugged the blogpost on Twitter again but this time pitching to my academic audience.”

Boyer’s (1990) vision of scholarship of application rests on the use of scholarly knowledge for the greater good; “[s]uch a view of scholarly service – one that both applies and contributes to human knowledge – is particularly needed in a world in which huge, almost intractable problems call for the skills and insights only the academy can provide” (p. 22-23). The techno-cultural system of NPS enables scholars to develop public voice on free platforms like Twitter and connect with like-minded others for activism and awareness-raising, thus applying academic insights publicly to societal issues. Participants emphasized how Twitter enables female scholars, scholars of color, and scholars outside the prestige economy of tenure to contribute and lead.

@readywriting: “One of the things I appreciate about Twitter is the flattening effect in terms of whose voice carries weight. [There are] opportunities like the hashtag #notyourAsiansidekick that point out how academia is a shitshow for women and minorities in terms of ideas and influence being stolen…[there are] people whose social standing I might not have access to, even people I disagree with.”

@14prinsp: “So the real question is – what is my ‘professional identity’? Of course I am more than my blog or my tweets. I am more than my qualifications and my publications, too…[I]n my local context there are very few faculty that are online or using Facebook as a scholarly environment – I’m the odd one out and as an activist I’d like to use my own practices as an example of what is possible. I think it’s important to be an example of your vision of the profession, not just constrained by what’s done around you.”

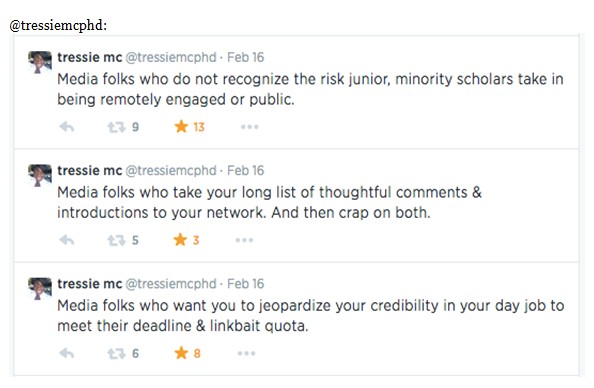

Participants also noted that NPS can be an avenue to media engagement and visibility, thus extending networks’ scholarship of application beyond the individual scale to an alternative institutional structure. Media visibility is not new to the NPS techno-cultural system of scholarship; the academy has always had scholarly superstars. The study suggests that NPS diverges, however, both in who is granted media attention and how it is received. The majority of participants who developed a significant media presence due to network scale and visibility were graduate students and early-career scholars, and many initially understood their respective opportunities as signals of success in a profession as reputation-dominated as academia. Yet many reported the decision to invest time in scholarship of application via media had been dismissed by senior faculty as frivolous, or had resulted in status tensions regarding their place within the academic hierarchy. Thus while NPS opens a new avenue to scholarship of application, the fact that its channels bypass institutional scarcity and hierarchy may render it illegible within the institutional prestige system.

Furthermore, while media emerged as a channel for scholarship of application, and a means by which women, minorities, and junior scholars could engage openly as public thinkers and experts, the risks and payoffs for academics stepping beyond the institutional sphere appear as poorly understood in media circles as they are in institutional academic spheres. As some of the first professionals bridging the tensions of public knowledge dissemination in an age of information abundance, networked scholars offer insights into the challenges of contemporary scholarship of application.

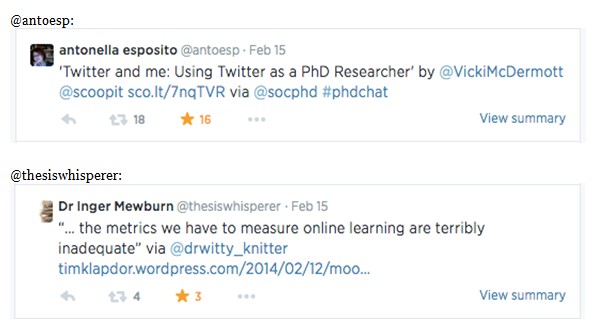

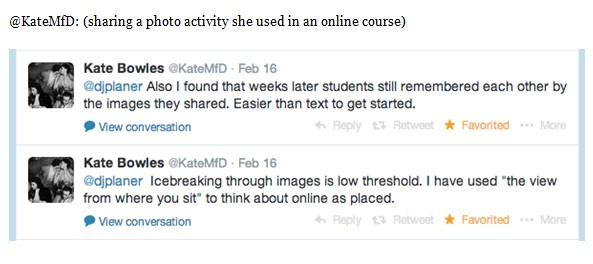

Boyer’s (1990) final form of scholarship is that of teaching. Teaching on Twitter can be overt, with scholars sharing syllabi and resources, using Twitter hashtags to coordinate open conversations within and between courses, and participating in endeavours like the #SaturdaySchool hashtag, which explores social justice issues in education. It can also consist of less formalized teaching and learning activities, such as scholars sharing practices and stories to explore contemporary issues, or to offer perspectives on approaches that have worked for them.

Boyer (1990) frames the scholarship of teaching as an identity as much as an act; “[G]ood teaching means that faculty, as scholars, are also learners…Teaching, at its best, means not only transmitting knowledge, but transforming it and extending it” (p. 23-24). This identity approach to teaching aligns with the public, cross-disciplinary nature of NPS; what scholars share and re-tweet serves as a statement not only about what teaching is, in their contexts, but what they believe it should be. NPS thus operates as an open, public conversation on teaching – and learning about teaching – for all interested contributors, regardless of their teacher or student status. This blurring of hierarchy between who teaches and who learns, and the fact that teaching and learning become public acts fostering public engagement, mark the techno-cultural system of NPS as distinct from the scarcity-based system of institutional scholarship.

Finally, both abundance and scholarship of teaching emerge as central to NPS techno-cultural practices in the ways participants enrol networked peers into their teaching discussions and their classrooms. A robust network of cross-disciplinary peers who have some technological capacity opens up instructors’ potential to expose and connect their classes to a wide range of online experts and resources. Such connections, evident throughout the research, enable students to engage directly and – after first introduction, individually and independently – not only with various experts but with the extended networks experts provide entry to, at scale and regardless of geographic distance. Through guest lectures, hashtags, public calls for comments on students blogs, and other invitations to engage, participants who were actively teaching offered their students precisely this expanded and accessible manifestation of knowledge abundance in action.

The techno-cultural practices that constitute NPS, then, align quite closely with Boyer’s vision for scholarship in all four components. Networks particularly advantage scholarship of integration, application, and teaching, since as a system, NPS is premised on cross-disciplinary, public, and teaching-focused practices in ways academia is not. However, Boyer’s four components did not fully encompass the terms or value of networked scholarship as presented by study participants; rather, their accounts suggest NPS may enact Boyer’s initial aim of broadening scholarship’s concept of itself by exceeding the scarcity-based limitations of the existing status quo.

Boyer (1990) critiques the increasing restriction of scholarship to a “hierarchy of functions” (p. 15) with research and publication at its top. He situates this hierarchy against the broader historical meaning of scholarship, and argues for the return to a more inclusive, comprehensive and dynamic definition that reflects “more realistically the full range of academic and civic mandates” (Boyer, 1990, p. 16). This is, this paper suggests, the distinct techno-cultural system that networked scholarship represents. While certainly overlapping on many fronts and values with the techno-cultural system of institutional, legacy scholarship and the academic publishing system, NPS opens up this “hierarchy of functions” and releases scholars from the residual prestige of scarcity enshrined in that system, at least at this juncture.

@catherinecronin: “My role is a hybrid admin-academic role – as far as the university is considered I’m half and half but I consider myself an educator, so my networked participation is much more fulfilling, less limiting than my job title… I couldn’t live without that network because the way that I work and teach and learn is different from my immediate peers where I sit at the university – the level of exchange and challenge that I get on Twitter is really important to me.”

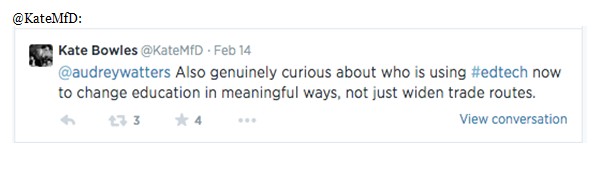

@KateMfD: “For me, being out here is about remaking the university in a different place. My natural companion set as a networked educator has proved to be the people interested in alternative models. There’s a Thomas Hardy poem about sitting in Salisbury Cathedral and not being a believer – and that’s my relationship to higher ed...[M]y networked practice is much more closely aligned to my personal values, and much more completely achieved. My networked identity feels like something that has been allowed to develop in its own time, and to represent things that I really care about, or questions I have been genuinely curious to pursue. So, the irony: I think I am a much better academic in my networked practice than in my actual work.”

@thesiswhisperer: “The network is where my peeps are. They’re not around me physically; there’s no one I really connect with as a scholar here – I’m an academic hobo at my institution because there’s no education or architecture school – and I find that liberating. All my scholarly work goes on collaboratively online.”

@exhaust_fumes: “In the last couple of years I’ve had a concerted social media strategy to make sure I have a community not tied to my particular job…I love conferences but the benefit of Twitter over a conference is the sheer amount of time. It’s ongoing, it’s forever…it enhances conferences because it’s motivating and helps you feel other people are engaged in the same things as you.”

The complex techno-cultural system that is scholarship, then, currently manifests in two overlapping but very distinct sets of practices. Veletsianos and Kimmons (2012) posit scholarship generally as “ever changing in response to both internal and external stimuli, including technological innovations and dominant cultural values” (p. 773), but this study suggests that change responses may have penetrated so differentially that two spheres or systems can be said to exist. Embedded in both, the study’s participants indicate that NPS is indeed scholarship, but a new scholarship premised in abundance rather than scarcity. The techno-culture system of NPS privileges the hybridity, multiplicity, and public boundary work of knowledge abundance in ways that institutional scholarship cannot do so long as it remains bound to traditions of scarcity, particularly around publishing and prestige.

Yet, if NPS currently fosters a breadth of scholarly engagement, connections, and identities that do not align with the practices and outlooks to which much of the academy is still acculturated, what does this suggest for the future of scholarship as a techno-cultural system? Going forward, it seems unlikely that NPS and institutional scholarship will continue to develop in divergent directions. Knowledge production is an economic entity in addition to its many other societal contributions, and while NPS has opened up some avenues to informal professionalization and monetization of scholarship, the institutional system of scholarship still controls and to an extent protects the formal professional avenues represented by concepts such as tenure and academic freedom. Thus networked scholars may value the techno-cultural system of NPS, but many remain economically dependent on the institutional system. As Phipps (2013) notes, a network “does not diminish the importance of the institution to the individual…the structures to support individuals form the platform upon which profiles are built” (p. 14). And while digital networks’ convenience and visibility are increasingly acknowledged within the institutional sphere (Mewburn & Thompson, 2013), and scholars are exhorted to “go online” to increase institutional revenue or relevance, this encroachment of institutional presences and premises into networked spaces does not necessarily honor the tenets of NPS as a system of scholarship in abundance.

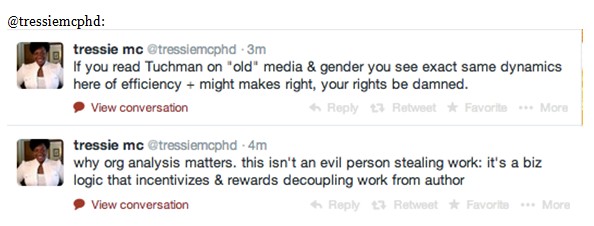

@tressiemcphd: “Academics would love if they could recreate our institutional prestige hierarchy online but they can’t…[W]e are rewarded for not being aware of social media, there’s a perverse incentive to not be engaged with it. But there are competitive market pressures to matter to the public…so to resolve that, what senior scholars are doing is “Okay, I’m not going to engage it as an actual social space.” When I give talks, the thing I tell them is you can be a broadcaster or an engager; instantly when I say engagement they react like “Nobody’s gonna talk back at me.” So the way they’re managing that is by saying, I will only allow these things that exist in my material world – The Chronicle or whatever – to talk back to me. That’s the extent of their real digital engagement. That’s them trying to manage all that change, to say “No, I’m there” but to have nobody ever talk back at them.”

Ultimately, the tensions between practices of scarcity and practices of abundance in knowledge production are made visible in networked scholarship. Approached as a techno-cultural system, NPS aligns with and enacts the terms of scholarship envisioned by Boyer (1990). Networks emphasize sharing and citation, as the academy does, but reward connection, collaboration, and curation between individuals rather than roles or institutions. NPS also fosters extensive cross-disciplinary and public ties for scholars, and encourages scholars to be teacher-learners who engage and speak back in the midst of multiplicity and abundance. Networks extend scholarly participation beyond the walls of university and operate, in effect, as a new techno-cultural system as scholarship of and for the context of knowledge abundance.

However, this techno-cultural system may be distinct from the institutional model of scholarship – to the limited but meaningful extent to which this research shows that it is distinct – only briefly, depending on the future trajectories that knowledge production, networks, and institutions variously take. Participants in the study emphasized that networks face growing encroachment from institutional entities and scarcity-based mindsets. As a backdrop to this encroachment, it is particularly important to note the fact that networks do not function as a separate techno-cultural system of scholarship in the economic sense. Thus, the forms of recognition that NPS is beginning to attract from institutional circles may serve to institutionalize and rationalize the open curation and sharing that this study found at the heart of networked scholarship, while alternative sources of economic support for networked practices may serve – or at least attempt – to monetize them. Future research into the tensions between abundance and scarcity in terms of what counts as knowledge will need to take economic elements into account.

In conclusion, then, this study captures NPS’ fledgling enactment of a scholarship of abundance, which may be important for scholarly communities seeking to understand how the values of scholarly inquiry can be honoured and aligned within a sociomaterial context of knowledge abundance. Concurrently, the study suggests that opening up academic practices of scarcity might do a great deal to help scholarly values remain relevant in an era premised in abundance. However, further examination of the economic and prestige drivers of institutional scholarship is needed to assess barriers to the widespread uptake of networked scholarship in the service of abundance. This examination remains outside the boundaries of this study, but will be a rich site of future investigations within distributed and networked education and scholarship.

Becker, J. (2015, January 15). Hiring a network [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.jonbecker.net/hiring-a-network/

Boellstorff, T., Nardi, B., Pearce, C., Taylor, T.L. (2012). Ethnography and virtual worlds: A handbook of method. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

boyd, d. (2011). Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implications. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A networked self (pp. 39-58). New York, NY: Routledge.

Boyer, E. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton, NJ: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Brin, S., & Page, L. (1998). The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual web search engine. Computer Networks and ISDN Systems, 30(1-7), 107–117. Retrieved from http://infolab.stanford.edu/~backrub/google.html

Bruns, A. (2007). Produsage: Towards a broader framework for user-led content creation. Creativity & Cognition, 6. Retrieved from http://produsage.org/files/Produsage%20(Creativity%20and%20Cognition%202007).pdf Clawson, D. (2009). Tenure and the future of the university. Science, 324, 1147-1148.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (2009). Signs of epistemic disruption: Transformations in the knowledge system of the academic journal. First Monday, 14(4-6). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/article/view/2309/2163

Daniels, J. (2013, June 27). Legacy vs. digital models of academic scholarship [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://justpublics365.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2013/06/27/legacy-vs-digital-models-of-academic-scholarship/

De Zepetnek, S. T. & Jia, J. (2014). Electronic journals, prestige, and the economics of academic journal publishing. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, 16(1), 1-13.http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2426&context=clcweb

Eisner, E. W. (1991). The enlightened eye: Qualitative inquiry and the advancement of educational practice. New York: Macmillan.

Ellison, J. & Eatman, T. K. (2008). Scholarship in public: Knowledge creation and tenure policy in the engaged university. Imagining America: A Resource on Promotions and Tenure in the Arts, Humanities, and Design. Retrieved from http://artsofcitizenship.umich.edu/documents/TTI_FINAL.pdf

Eye, G. G. (1974). As far as eye can see: Knowledge abundance in an environment of scarcity. The Journal of Educational Research, 67(10), 445-447.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of culture. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gibson, W.J. & Brown, A. (2009). Working with qualitative data. London: SAGE.

Gruzd, A., Staves, K., Wilk, A. (2012) Connected scholars: Examining the role of social media in research practices of faculty using the UTAUT model. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(6), 2340–2350. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.004

Guba, E.G. & Lincoln, Y.S. (2005). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed), (pp. 191-215). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Harley, D., Krysz Acord, S., Earl-Novell, S., Lawrence, S, & Judson King, C. (2010). Assessing the future landscape of scholarly communication: An exploration of faculty values and needs in seven disciplines. Center for Studies in Higher Education, UC Berkeley. Retrieved from http://escholarship.org/uc/cshe_fsc

Hurt, C. & Yin, T. (2006). Blogging while untenured and other extreme sports. Berkman Center for Internet & Society. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=898046

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Law, J. (2009). Actor network theory and material semiotics. In B.S. Turner (Ed.), The New Blackwell companion to social theory (3rd ed), (pp. 141–158). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mewburn, I. & Thompson, P. (2013, December 12). Academic blogging is part of a complex online academic attention economy, leading to unprecedented readership. LSE Impact Blog. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2013/12/12/academic-attention-economy/

Munro, D. (2015, January 6). Where are Canada’s Ph.Ds employed? The Conference Board of Canada. Retrieved from http://www.conferenceboard.ca/topics/education/commentaries/15-01-06/where_are_canada_s_phds_employed.aspx

Pearce, N., Weller, M., Scanlon, E. & Kinsley, S. (2010). Digital scholarship considered: How new technologies could transform academic work in education. In Education, 16 (1).

Phipps. L. (2013). Individual as institution. Educational Developments, 14(3), p. 13-14.

Schmitt, J. (2014, December 23). Academic journals: The most profitable obsolete technology in history. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jason-schmitt/academic-journals-the-mos_1_b_6368204.html?utm_hp_ref=tw

Seaman, J., & Tinti-Kane, H. (2013). Social media for teaching and learning: Annual survey of social media use by higher education faculty. Pearson Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.pearsonlearningsolutions.com/higher-education/social-media-survey.php

Stewart, B. (2015). Open to influence: What counts as academic influence in scholarly networked Twitter participation. Learning, Media, and Technology, 40(3), 1-23. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2015.1015547

Terras, M. (2012, April 19). The verdict: Is blogging or tweeting about research papers worth it? LSE Impact Blog. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2012/04/19/blog-tweeting-papers-worth-it/

VanNoorden, R. (2014, August 13). Online collaboration: Scientists and the social Network. Nature: International Weekly Journal of Science, 512(7513). Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/news/online-collaboration-scientists-and-the-social-network-1.15711?WT.mc_id=TWT_NatureNews

Veletsianos, G. & Kimmons, R. (2012). Networked participatory scholarship: Emergent techno-cultural pressures toward open and digital scholarship in online networks. Computers & Education, 58(2), 766-774.

Veletsianos, G. (2013). Open practices and identity: Evidence from researchers’ and educators’ social media participation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4), 639-651. doi: :10.1111/bjet.12052

Weller, M. (2011). A pedagogy of abundance. Spanish Journal of Pedagogy, 249, 223- 236.

White, D. S., & LeCornu, A. (2011). Visitors and residents: A new typology for online engagement. First Monday, 16(9). doi:10.5210/fm.v16i9.3171

Willinsky, J. (2006). Why open access to research and scholarship? The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(36), 9078-9079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2891-06.2006. Retrieved from http://www.jneurosci.org/content/26/36/9078.full

Willinsky, J. (2010). Open access and academic reputation. Annals of Library and Information Studies, 57, 296-302. Retrieved from http://nopr.niscair.res.in/bitstream/123456789/10242/4/ALIS%2057%283%29%20296-302.pdf

© Stewart