Jennifer C Richardson, Adrie A. Koehler, Erin D. Besser, Secil Caskurlu, JiEun Lim, and Chad M. Mueller

Purdue University, United States

As online learning opportunities continue to grow it is important to continually consider instructor practices. Using case study methodology this study conceptualizes instructor presence, the intersection of social and teaching presence as defined within the Community of Inquiry literature, and is based in the implementation phase of online courses which is important to note since instructors often teach courses they did not design or develop. The investigation of the instructor presence behaviors of 12 online instructors and the emerging profiles of instructor presence provide a gateway to strategies for online instructors and offer a window into the ways instructional presence elements work together while providing insights into how to make the best use of online instructor time. In practical terms, the profiling method provides a useful way for practitioners to improve their own experiences.

Keywords: Distance education; online education; community of inquiry; instructor presence

The past decade has seen an unswerving increase in online learning (Allen & Seaman, 2013). Although online education offers many exciting opportunities, it also presents a number of challenges. For example, many instructors are being asked to teach online with little to no previous experience, and have reported difficulty determining how to make the best use of their time in the online environment (Van de Vord & Pogue, 2012). Also, students participating in online courses have reported that they feel disconnected from their peers and instructor, struggle to understand instructional goals, and miss receiving real-time feedback (Kim, Liu, & Bonk, 2005; Kruger-Ross & Waters, 2013; Song, Singleton, Hill, & Koh, 2004). Many of these reported challenges relate to the frequency, type, and timing of communication methods used in developing relationships and interpersonal connections in the online environment (Swan, 2002).

Researchers have reported that an instructor’s ability to establish his/her presence in an online course can potentially mitigate these challenges (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2007; Swan, 2002). However, many online instructors have insufficient guidance for enacting their presence in online environments. This study conceptualizes and investigates the concept of instructor presence, the intersection of social and teaching presence as defined within the Community of Inquiry literature, allowing us to glimpse what instructor presence looks like in practice.

To consider the dynamics and challenges present in online instructional environments, many scholars have utilized the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework to ensure that research explorations are completed in a meaningful and efficient manner (Garrison, 2007). The CoI framework is comprised of three key constructs: social presence, teaching presence, and cognitive presence, and contends that the resulting online educational experience for students is determined by how these three elements interrelate. In general, students reported that feelings of isolation relate to the construct of social presence, while instructors’ approaches to addressing this specific challenge relates to the construct of teaching presence (Anderson, Rourke, Garrison, & Archer, 2001; Richardson & Swan, 2003).

Social presence in online learning is commonly defined as the degree to which participants feel connected to one another in an online community (Boston, Diaz, Gibson, Ice, Richardson & Swan, 2009; Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007; Oztok & Brett, 2011). The CoI framework characterizes it as the elements of affective expression (“where learners share personal experiences of emotion, feelings, beliefs, and values”), open communication (“where learners build and sustain a sense of group commitment”), and group cohesion (“where learners interact around common intellectual activities and tasks”) (Swan, Garrison & Richardson, 2009, p. 52). These elements are designated by indicators for affective (e.g., paralanguage, emotions, humor), cohesive (e.g., greetings, vocatives, social sharing), and interactive (e.g., invitation, approval, advice) responses (Swan, et. al., , 2009, p. 52). In practice, a number of instructional strategies and behaviors (e.g., providing students timely feedback, using audio feedback, and using digital storytelling) have been found to enhance social presence (Aragon, 2003; Lowenthal & Dunlap, 2010; Rourke, Anderson, Garrison & Archer, 1999). Furthermore, there is general agreement that social presence plays a mediating role for both teaching presence and cognitive presence within a Community of Inquiry (Garrison, 2011; Garrison & Akyol, 2013; Kozan & Richardson, 2014; Oztok & Brett, 2011; Shea, Vickers, & Hayes, 2010).

Moreover, research has demonstrated that social presence is related to students’ actual and perceived learning (Hostetter & Busch, 2013; Picciano, 2002; Richardson & Swan, 2003). Researchers have reported a positive relationship between students’ perceived social presence and their satisfaction with their instructors (Richardson & Swan, 2003), with their courses (Akyol & Garrison, 2008; Hostetter & Busch, 2006), as well as with retention rates in online courses (Boston, et. al., 2009). These findings point to the importance of social presence in the learning process.

Teaching presence is also a critical aspect in creating effective online learning communities. Garrison et al. (2000) argued that even though both social and content-related interactions among participants are necessary in online communities, online interactions are not enough to ensure effective online learning. For this reason, teaching presence is considered important in directing these interactions. Teaching presence represents “the ‘methods’ that instructors use to create the quality online instructional experiences that support and sustain productive communities of inquiry” (Bangert, 2008, p. 40). Teaching presence behaviors utilized by online instructors can be broken into specific categories: design and organization (“the planning and design of the structure, process, interaction, and evaluation aspects of the online course”), direct instruction (“the instructor provision of intellectual and scholarly leadership in part through the sharing of their subject matter knowledge with the students”), and facilitating discourse (“the means by which students are engaged in interacting about and building upon the information provided in the course instructional materials”) (Swan, Shea, Richardson, Ice, Garrison, Cleveland-Innes & Arbaugh, 2008, p. 3). Finally, a more recent fourth category, assessment, includes “both formative and summative assessment across a broad range of instructor and student activities that occur within an online course” (Shea et al., 2010, p. 134).

In addition to defining teaching presence, efforts have been made to identify what teaching presence looks like in practice (Swan, 2002; Shea, et al., 2006; Shea et al., 2010). For instance, using survey data, Shea et al. (2006) found that students were “significantly more likely to report higher levels of learning and community when they perceived higher teaching presence behaviors” (p. 185). Similarly, Kupczynski, Ice, Wiesenmayer, and McCluskey (2010) found that, depending on student level (i.e., undergraduate vs. graduate), students perceived different teaching presence factors related to their success (e.g., direct instruction, facilitation, and discourse) or lack of success (e.g., lack of feedback, unclear course communications) in an online course.

Emerging from the intersection of social presence and teaching presence is the concept of instructor presence. In some cases to date, this term appears to be used interchangeably with teaching presence (Lear, Isernhagen, LaCost, & King, 2009; Sheridan & Kelly, 2010). However, there are distinct differences between these two constructs in that instructor presence is based on more observable instructional behaviors and actions than teaching presence. In other words, instructor presence is more likely to be manifested in the “live” part of courses—as they are being implemented—as opposed to during the course design process. This is important to note since instructors often teach courses they did not design or develop and this practice continues to grow as online learning enrollment numbers continue to grow.

Synthesizing literature focused on aspects of instructor presence is insightful. Students value many actions, attributes, and behaviors of instructors and likely develop a perception of an instructor’s presence from their observations of what has been traditionally considered either social or teaching presence. Wise, Chang, Duffy, and Valle (2004) describe instructor social presence as a factor enabling learners to see their instructors as caring, helpful people. Research reveals that students value instructors who are responsive to their needs (Hodges & Cowan, 2012; Sheridan & Kelly, 2010). Additionally, an aspect of instructor presence is instructor immediacy. Based on the reviewed research, instructors reduced the student perception of distance through timely responses and feedback, and developing a sense of community with students (Hodges & Cowan, 2012; Sheridan & Kelly, 2010). Students rated clear directions and course requirements as one of the most important aspects of instructor presence (Hodges & Cowan, 2012; Sheridan & Kelly, 2010). Synthesizing these ideas, we are defining instructor presence as the specific actions and behaviors taken by the instructor that project him/herself as a real person. In other words, instructor presence relates to how an instructor positions him/herself socially and pedagogically in an online community, and would fall at the intersection of teaching presence and social presence within the CoI framework.

Breaking down this construct and describing specific cases of instructor presence allows us to gain a deeper understanding of the online instructor processes, and to consider specific instructor actions, interactions, and styles influencing this process. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the construct of instructor presence in an online environment. Specifically, the following research questions guided this study:

How is instructor presence conceptualized and how do online instructors incorporate instructor presence in their courses?

How do specific actions and behaviors taken by instructors come together to form profiles of instructor presence?

To examine instructor presence in online environments, this research used a descriptive multiple-case study approach (Yin, 2009) with the intent to both build an explanation of instructor presence behaviors and actions and conduct a cross-case synthesis. Descriptive case studies are useful in describing “an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred” (Baxter & Jack, 2008, p. 548), and using this approach while considering instructor presence in an online instructional environment affords the opportunity to consider this construct while relying on the literature to guide the process (Yin, 2014).

At the same time, using a multiple-case study approach provides the opportunity for a more robust and reliable study and can overcome weaknesses (e.g., uniqueness and artificial conditions) associated with single case studies (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Yin, 2014). By analyzing multiple cases, instructor presence can be more fully understood, as this phenomenon was considered both from studying the individual instructor’s approach and the combined methods of all instructors in an online program. Additionally, by examining instructor presence across 12 instructors and 4 courses, we can begin to develop profiles of online instructor presence, or build an explanation of such (Yin, 2009). As a framework for understanding instructor presence, we used the CoI framework and focused on the juncture of teaching presence and social presence, the area that is conceptually most aligned with the role of the instructor.

The data were gathered from an online Master’s Program in Learning Design and Technology (LDT) at a large Midwestern public university. The online Master’s Program is a 20-month, fully online program which enrolls approximately 200 students on a continuous basis. Courses in the program run eight weeks in length.

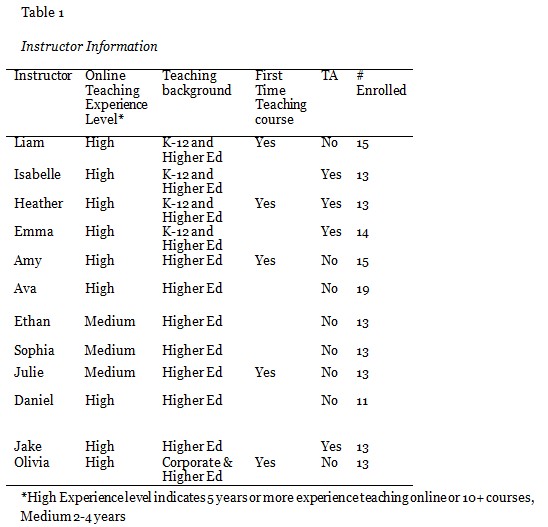

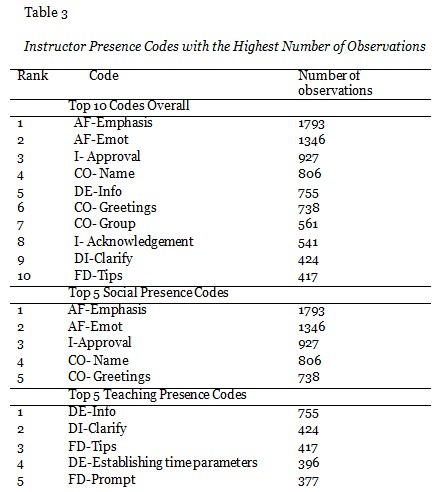

This study examined the instructor presence of 12 instructors in these sections allowing for individual instructors to be the unit of analysis. Instructors for these courses include both full-time university faculty members (n=3) and limited-term lecturers (n=9). Table 1 presents information regarding instructor information; pseudonyms were assigned.

Purposive sampling was employed when selecting instructors for the study. In this research, three required courses were selected to explore instructor presence: EDCI 53100 (Learning Theories and ID), EDCI 57200 (Learning Systems Design), and EDCI 67200 (Advanced Practices in Learning Systems Design). These courses were chosen as they represent three diverse experiences and perspectives including both introductory and advanced coursework. These sections were offered during the summer and fall of 2013 and spring of 2014. The courses were designed by full-time faculty members and common elements (e.g., weekly overviews, discussion question prompts) across each section of a course were present.

From Blackboard, instructors’ communications, interactions, and actions were collected for each course instructor within the learning management system. Any interactions that may have occurred outside of the BB system (e.g., e-mail communications with students) were not included as we did not have complete access to those aspects for each instructor. The data sources were coded at the sentence level.

To conceptualize instructor presence and answer the first research question, the research team began by developing instructor audits or individual instructor case studies (Creswell, 2014, p. 193). We developed a coding schema which was based on social presence and teaching presence indicators presented by previous researchers (Akyol, 2009; Rourke et al., 1999; Shea et al., 2010; Swan, 2002); deductive and inductive methods were utilized. After piloting the initial codes, the research team met on multiple occasions to further enhance the coding schema through an analytic induction process that included (1) the development of emergent codes, (2) broadening or narrowing of previous codes, (3) collapsing codes, and (4) deletion of codes not related to the instructor’s actions or behaviors.

Considering that the previous teaching and social presence indicators and codes were based not only on instructor’s actions and behaviors but also student action and behaviors, our first step was to delete codes that were not directly related to our instructors. Next, codes were modified generally based on a need to narrow, broaden, or fine tune codes, based on their previous use. For example, Swan’s “social sharing”, “course reflection”, and “paralanguage” were modified in our coding schema (2002). Social sharing was broken out into several other codes, including Affective (AF)-Self-disclosure, AF-Value, and AF-Humor. Paralanguage had previously been used to convey emotions outside of formal text (Swan, 2002, p. 37); in our case, we found some paralanguage examples were based in emotion while others were used to add emphasis (e.g., due date reminders). This also led to the code AF-Emphasis being added. An example of broadening a code is Shea et al.’s (2010) Summarizing Discussion to our facilitating discussion (FD-Summ) to be inclusive of all course activities and not just discussions. Additionally, the development of emergent codes was an ongoing process that mostly began with noting codes that seemed to fall outside current codes. Finally, we felt it was necessary to include new social presence Cohesive codes (CO) related to collaboration and diversity—two aspects that the program in the study has been working to integrate. The new codes were piloted and modified or collapsed in a number of cases. Emergent codes were considered acceptable once 5 or more instances were located within the data. See Appendix A for the final coding schema with definitions, examples, notes on revisions, and number of observed occurrences.

Upon reaching the point of saturation within the codes (Creswell, 2014), the final coding schema led to 43 items focusing on the two main categories: teaching presence (28 indicators) and social presence (15 indicators). A total of 12,602 references were coded.

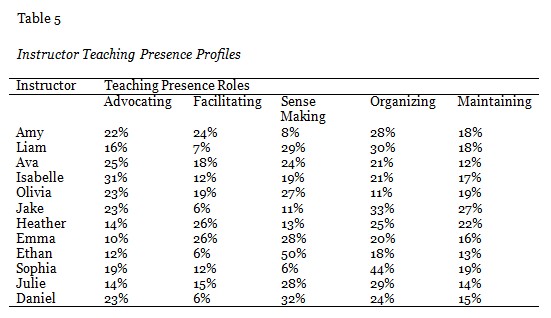

For the second research question, using the indicators as a descriptive framework, the research team organized and grouped data to form instructor presence profiles (Yin, 2014). Specifically, this process was completed by making connections across teaching presence categories through grouping similar indicators together. Once indicators were grouped based on similarity, prominent roles were identified in order to describe and classify the indicators. Then, for each instructor, a teaching presence profile was constructed by calculating the percentage each role represented of the total number of indicators observed in a particular course. Finally, social presence indicators were considered in combination with the teaching presence profiles. For each of the roles indicated from the teaching presence indicators, ways that social presence indicators enhanced the instructional approach were identified and described.

In order to establish the reliability of the coding procedure, three researchers independently coded instructors’ postings allowing for triangulation of coding. We then compared the results and consensus building allowed for 100 % inter-coder agreement for all courses (Creswell, 2014). Additionally, the research team avoided “code drifting” by meeting regularly and discussing any misunderstandings or uncommon coding aspects as they arose (e.g., peer debriefing) (Creswell, 2014, p. 203).

When ensuring validity of the research, it is important to note that each member of the research team was familiar, either as a student or instructor, with the online program under study, which allowed for insight into the general operations of and layout of the courses (e.g., prolonged engagement). We attempted to overcome any bias in their association with the program by engaging in researcher reflexivity (Creswell, 2014), and ensuring no researcher coded a course in which they were enrolled, served as an instructor/teaching assistant, or was taught by their advisor. As the coding schema developed over time, an audit trail was kept to remind the team where we had been, decisions we had made, and questions we planned to revisit as the schema evolved (Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014).

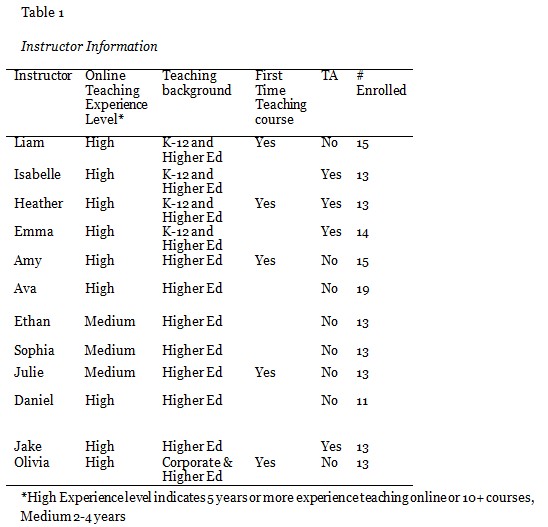

Case studies were developed for the twelve instructors and commonalities and differences were noted as a means to better understand what was happening across the courses and what instructor presence “looked like”. Instructors’ involvement levels were the highest in discussion and announcement portions of the courses as was anticipated. As researchers we determined that quantitative content analysis would not be effective as various codes hold more weight than others. In other words, a coded segment that provides a detailed explanation or example would take more effort for an instructor versus a coded segment that was based on highlighting a due date yet each would count as 1 coded segment. However, using the codes is a useful descriptive tool. As evidenced in Table 2, the number of codes for instructors ranged from 478-2,792 for a single course. We can also see that a number of our instructors were fairly balanced (45-55% or 55-45%) between social presence and teaching presence codes. All but three instructors had an equal or greater number of social presence codes compared to teaching presence codes.

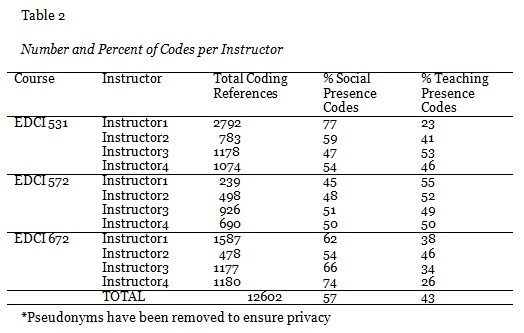

The categories for the social presence (Affective, Cohesive, Interactive) and teaching presence codes (Design and Organization, Direct Instruction, Facilitating Discussion, and Assessment) were examined to identify potential patterns in the instructor cases. For each instructor, the two categories with the most observed indicators were identified (see Table 3). Across all instructors, the categories that were most prevalent were Affective (AF) (n=7), Design and Organization (DE) (n=7), Interactive (I) (n=5), and Cohesive (CO) (n=3). Direct Instruction (DI) was only the most popular for one instructor and Assessment (AS), as would be expected, was not the most popular for any instructor. However, it was interesting to note that Facilitating Discourse (FD) was also not highly represented.

Next, we examined the instructor cases for specific codes from within the categories, specifically the number of observations. Table 3 shows the codes with the highest number of observations.

Interestingly, of the top ten codes observed across the cases, seven fell within the social presence category. However, a closer look at the actual categories reminds us of the differing weight that should be given to codes based on instructor effort. Codes such as AF-Emphasis (e.g., highlighting), AF-Emotions (e.g., the use of text, emoticons, or unusual punctuation to express “nonverbal” emotions), and CO-Name (e.g., use of student’s name) are easily added without much instructor effort, yet are very important in the scope of the instructor role. The top five teaching presence indicators tell us that the instructors’ actions and behaviors go a long way to trying to help keep students on track and informed (e.g., establishing time parameters for learning activities), clarifying misunderstandings, providing tips on how to succeed, and moving their thinking and knowledge forward through the use of required prompts. By looking at the most common codes observed, we can get a sense of the instructors’ role in an online course and even the ease of being present with behaviors and actions that are not very time consuming (e.g., due date reminders).

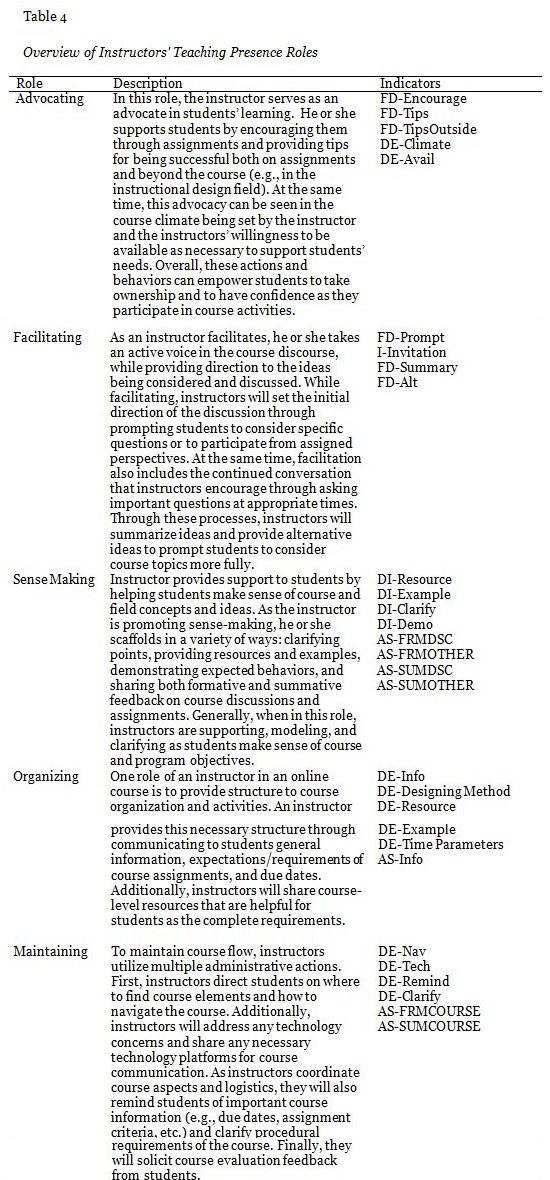

To develop meaningful profiles for researchers and practitioners we began by identifying prominent instructional roles, by grouping similar teaching presence indicators together. From this process, five distinct instructional roles emerged: advocating, facilitating, sense making, organizing, and maintaining.

While teaching presence is a well-established construct (Garrison et al., 2000, 2001) and a number of indicators for teaching presence have been established (Shea et al., 2010), the roles described here attempt to connect aspects of the teaching presence construct across teaching presence categories. Table 4 includes a full description of each role and the indicators that illustrate that role.

Considering how the various roles work together is very useful in describing an instructor’s teaching presence. For instance, an instructor whose teaching presence is dominated by administrative roles projects a different presence than an instructor whose prominent teaching roles consist of facilitating and helping students make sense of the course’s various activities. At the same time, examining the combination of the roles is interesting when considering the ways in which an instructor teaches a course. Some instructors dedicate time consistently across many roles, while others direct efforts to primarily one or two roles. While the ideal combination of roles is unclear, an instructor who dedicates their time to only one or two roles may have gaps in his or her teaching presence (Anderson et al., 2001).

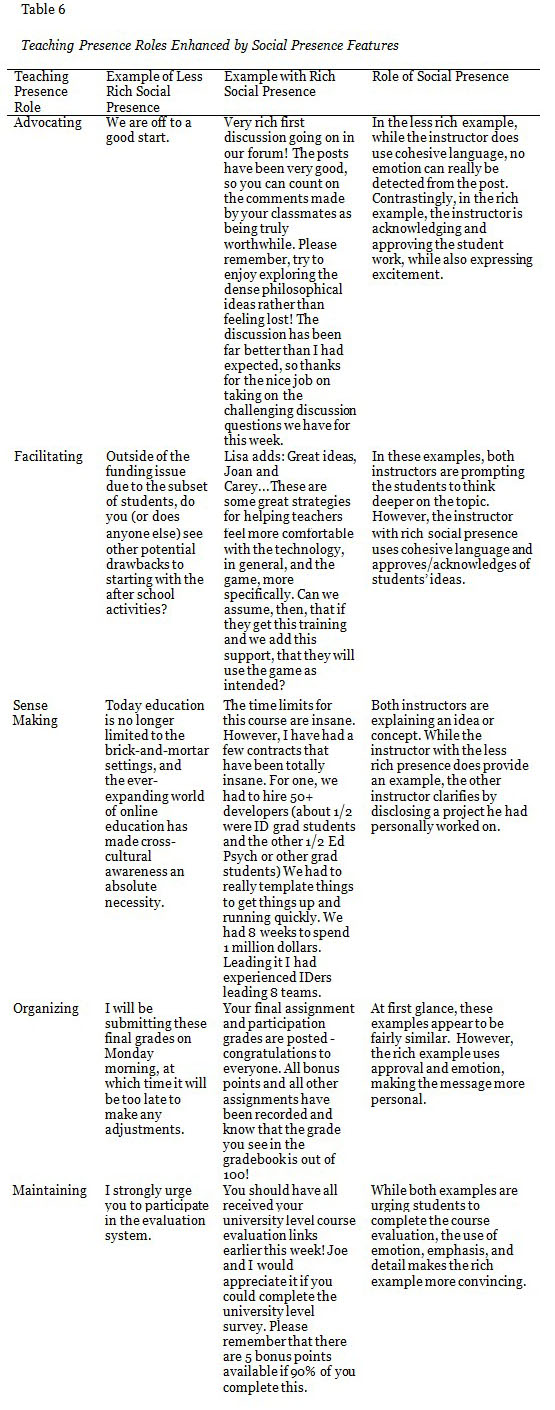

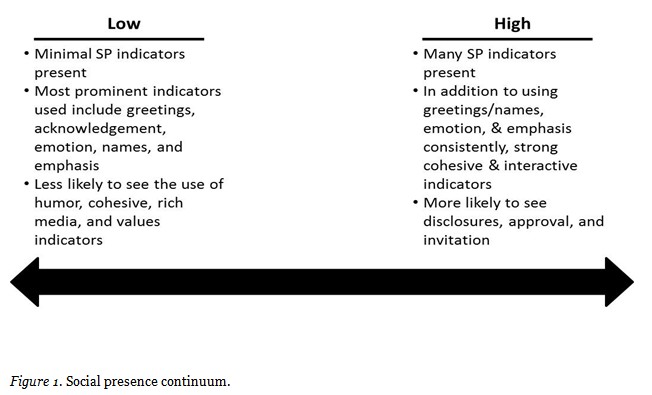

Next, as the instructor presence profiles were constructed, social presence indicators in the courses were considered. In this sense, social presence indicators represent characteristics of instructors, as social presence represents a communication style or the adaptation of a specific communication medium (Dunlap & Lowenthal, 2014) and therefore characteristics that enhanced their teaching presence roles. As an instructor teaches a course, he or she exhibits a certain amount of social presence depending on the particular actions and behaviors taken (Aragon, 2003; Bangert, 2008). At the same time, as instructors project their presence in one of the teaching presence roles, they may exhibit higher or lower social presence. For example, as Olivia advocates for students, her social presence is very high yet her social presence level is moderate when facilitating and organizing, and low when sense making and maintaining.

When considering the role of social presence features in instructor presence, a couple of aspects must be acknowledged. First, the number of observed indicators can impact an instructor’s presence. For instance, students will likely have different perceptions of an instructor who discloses only a few pieces of information compared to an instructor who actively shares personal details. Second, an instructor’s use of social presence indicators can communicate a specific overall style to students (e.g., formality vs. informality). Finally, when considering the role of both teaching presence and social presence in forming instructor presence profiles, the interaction between these elements appears to be essential (Bangert, 2008). Specifically, social presence indicators appear to play an enhancing and enabling role (Bangert, 2008; Schutt, Allen, & Laumakis, 2009; Swan & Shih, 2005) to the five teaching presence roles. When social presence indicators work with the teaching presence roles, the resulting instructor presence can be more meaningful and very powerful. Table 6 provides examples of how teaching presence roles can be enhanced by social presence indicators.

These samples highlight the richness social presence adds to a teaching presence role. While the message may be similar across the same role with or without social presence indicators, an instructor utilizing emotion or emphasis can communicate additional importance when sharing a due date—just like an instructor clarifying a concept can help promote deeper connections and sense making by sharing a professional experience. Figure 1 helps to demonstrate this conception.

This study examined the instructor’s role as a whole during the course implementation process. Instructor presence, at the intersection of social and teaching presence as defined within the CoI framework, allows researchers and practitioners to better understand that role regardless if an instructor is teaching a pre-designed course or is a course designer-instructor. Perhaps one of the most notable aspects of this study is the fact that the instructor plays so many roles and they use strategies across the continuum of the codes.

By examining the 12 instructor cases we were able to observe the activities of the instructors, the “what and how” of their actions and behaviors, allowing us to see what instructor presence looks like and provide insight into the behaviors and action of instructors as they go about their routines within an online course. Each indicator provides a definition and example which can serve as a gateway to strategies (See Appendix A). This can be especially helpful for those instructors new to online teaching and learning because when viewed as a playbook of strategies, they can use it as they embark on new ventures. Similarly, determining the balance between teaching presence and social presence can be difficult to gauge for new to online instructors. However, the instructors in this study demonstrate the multiple styles taken while also providing insight into that balance; in this case we found that instructor actions and behaviors were fairly balanced (45-55% or 55-45%) between social presence and teaching presence.

The instructors in this study also demonstrated the relative ease with which one can provide social and learning supports to students by the sheer number of “easily inserted” or low effort behaviors that include such effects as emphasis, use of student names, and reminders of upcoming due dates. As Van de Vord & Pogue (2012), reported many online instructors have difficulty determining how to make the best use of their time in the online environment and these observations help with that challenge. In addition, course designers equipped with more knowledge about what instructor presence looks like will enable the design of online learning environments where instructors are able to more effectively leverage strategies that enhance their presence. Specifically, shifting instructors’ attention on the importance of instructor presence can eliminate the common technological distractors associated with online teaching (Ladyshesky, 2013). Most importantly, instructors are able to begin to develop their own “online teacher personas” (Baran, Correia & Thompson, 2011; Richardson & Alsup, 2015).

While the focus of this study did not garner learner perspectives regarding instructor presence, it has been well documented that the online “social exchange” with their instructors is paramount to their own sense of social presence and overall satisfaction within an online learning environment (Boling, Hough, Krinsky, Saleem, & Stevens, 2012, p. 123; Liaw, 2008). Depending on whether an instructor showcases high or low levels of instructor presence can considerably impact this part of the teaching and learning dynamic. Thus, this study provides guidance for current and future online instructors to develop a deeper understanding of how to increase sense of community in the course, how to use social and teaching aspects of learning in online environments, and how to establish more effective online communication with learners.

What we observed also suggests that online teaching has indeed evolved since its major launch over a decade ago. By examining the list of indicators resulting from this study (See Appendix A) we can witness the evolution taking place in online environments as they become more commonplace. For example, we can see that the online instructors in this study transcend expectations of the early years of online learning—when providing direct instruction was considered the major task—and now incorporate a number of social presence behaviors to help students overcome the feeling of isolation, engage in a safe learning environment, and interact around common intellectual activities and tasks to build a community of inquiry. Moreover, the inclusion of new codes, such as our Cohesive codes (CO) for diversity and collaboration, demonstrate the evolution of what is important to us as instructors and designers in the area of online learning. We also know that this is an area to be visited and revisited again as the online learning community increases in number of instructors, students, new technologies, and online models.

The results of our second research question provide a rich description of instructor presence, as well as the various intricacies involved in its formation. The results highlight how instructor presence can vary even within the same course. Moreover, the profiles offer a window into the ways instructional presence elements work together.

In practical terms, the profiling method provides a useful way for practitioners to improve their own experiences. Examining specific instructor presence profiles reveals that social presence behaviors enhance the teaching roles that an online instructor assumes when teaching a course. Depending on whether an instructor utilizes high or low social presence actions can considerably change the resulting instructional efforts. While we cannot determine from this study if one profile is more meaningful than another, we can examine the roles and behaviors utilized individually and appreciate where there is room for improvement. By examining the sample profiles established here and the examples provided by instructor profiles, online educators can reflect on their own experiences, which in turn can help them locate strengths and weaknesses within their online instructional approaches. As Baran, Correia, and Thompson (2011) suggest, the research of online teaching practices not only informs future online design and teaching, but can provide a roadmap for the training and support of online instructors as well.

Limitations for this study include observations that were limited to the actions of the course instructor within a learning management system. Additionally, online educational programs vary in course structure, design, and teaching methods, and therefore, these findings may not apply to all online educational programs. This research focuses on a single graduate program and findings may not be applicable to other graduate programs, programs in other disciplines, or to undergraduate programs (Liu et al., 2005).

The limitations in our research suggest some important directions for further research. First, future research should explore the possibility of course design as a mediating factor for the role of instructor presence. Next, this study identified how instructors project their presence by analyzing their course postings; but further research should consider how instructors perceive their instructor presence and should identify the extent to which the instructors’ perceptions coincide with their behaviors. Future research should also seek to identify the students’ perceptions and attitudes toward instructor presence to the degree to which it impacts their perceived or actual learning and possibly allowing us to determine ideal profiles.

While the results from this study underscore the importance of instructor presence, more research is needed to confirm and to expand on these findings. As the prominence of the online learning format for instructional experiences continues to grow, understanding these constructs will ensure the further improvement of the online experiences for both students and instructors. As we have seen in the research, the role of the instructor has and will continue to evolve over time, as will instructor presence.

This project stemmed from a doctoral research seminar and we would like to extend our thanks to the other members of that course who were involved in the protocol development and data collection: Dr. Marisa Exter, Elizabeth Beese, Clark Cory, Steven Lancette, Yizhou Qian, Rodolfo (Rudy) Rico, and Lauren Sperlak.

Akyol, Z. (2009). Examining teaching presence, social presence, cognitive presence, satisfaction and learning in online and blended course contexts (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Middle East Technical University, Ankara.

Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2008). The Development of a community of inquiry over time in an online course: Understanding the progression and integration of social, cognitive and teaching presence. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3-4), 3-22.

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2013). Changing course: Ten years of tracking online education in the United States. Newburyport, MA: Sloan Consortium.

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teacher presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2), 1-17.

Aragon, S. R. (2003). Creating social presence in online environments. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2003(100), 57-68.

Bangert, A. (2008). The influence of social presence and teaching presence on the quality of online critical inquiry. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 20(1), 34-61.

Baran, E., Correia, A. P., & Thompson, A. (2011). Transforming online teaching practice: critical analysis of the literature on the roles and competencies of online teachers. Distance Education, 32(3), 421-439.

Baxter, P. & & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report , 13(4), 544-559. Retrieved on April 1, 2015 from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR13-4/baxter.pdf

Bawane, J., & Spector, J. M. (2009). Prioritization of online instructor roles: implications for competency‐based teacher education programs. Distance Education, 30(3), 383-397.

Boling, E. C., Hough, M., Krinsky, H., Saleem, H., & Stevens, M. (2012). Cutting the distance in distance education: Perspectives on what promotes positive, online learning experiences. The Internet and Higher Education , 15(2), 118-126.

Boston, W., Diaz, S., Gibson, A., Ice, P., Richardson, J., & Swan, K. (2009). An exploration of the relationship between indicators of the Community of Inquiry framework and retention in online programs. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 13(3), 67-83.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dunlap, J. C., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2014). The Power of presence: Our quest for the right mix of social presence in online courses. In A. A. Piña & A. P. Mizell (Eds.) Real life distance education: Case studies in practice (pp. 41-66). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishers.

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61-72.

Garrison, D. R. (2011). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Garrison, D. R., & Akyol, Z. (2013). The community of inquiry theoretical framework. In M. G. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of distance education (pp. 104-119). New York, NY: Routledge.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87-105.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7-23.

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the Community of Inquiry Framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(3), 157-172.

Hodges, C. B., & Forrest Cowan, S. (2012). Preservice teachers’ views of instructor presence in online courses. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 28(4), 139-145.

Hostetter, C., & Busch, M. (2006). Measuring up online: The relationship between social presence and student learning satisfaction. Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6(2), 1-12.

Hostetter, C., & Busch, M. (2013). Community matters: Social presence and learning outcomes. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol. 13, No. 1, February 2013, pp. 77 – 86.

Ke, F. (2010). Examining online teaching, cognitive, and social presence for adult students. Computers & Education, 55(2), 808-820.

Kim, K., Liu, S., & Bonk, C. J. (2005). Online MBA students’ perceptions of online learning: Benefits, challenges, and suggestions. The Internet and Higher Education, 8(4), 335-344.

Kozan, K. & Richardson, J. C. (2014). Interrelationships between and among Social, Teaching and Cognitive Presence. The Internet and Higher Education, 21, 68-73.

Kruger-Ross, M. J., & Waters, R. D. (2013). Predicting online learning success: Applying the situational theory of publics to the virtual classroom. Computers & Education, 61, 176-184.

Kupczynski, L., Ice, P., Weisenmayer, R., & McCluskey, F. (2010). Student perceptions of the relationship between indicators of teaching presence and success in online courses. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 9(1), 23-43.

Ladyshewsky, R. K. (2013). Instructor presence in online courses and student satisfaction. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 7(1), 13.

Lear, J. L., Isernhagen, J. C., LaCost, B. A., & King, J. W. (2009). Instructor Presence for Web-Based Classes. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal, 51(2), 86-98.

Liaw, S. S. (2008). Investigating students’ perceived satisfaction, behavioral intention, and effectiveness of e-learning: A case study of the Blackboard system. Computers & Education , 51(2), 864-873.

Liu, X., Bonk, C. J., Magjuka, R. J., Lee, S. H., & Su, B. (2005). Exploring four dimensions of online instructor roles: A program level case study. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(4), 29-48.

Lowenthal, P. R., & Dunlap, J. C. (2010). From pixel on a screen to real person in your students’ lives: Establishing social presence using digital storytelling. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1), 70-72.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Sage Publications.

Oztok, M., & Brett, C. (2011). Social presence and online learning: A review of research. Journal of Distance Education, 25(3).

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2007). Building online learning communities: Effective strategies for the virtual classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Picciano, A. G. (2002). Beyond student perceptions: Issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 21-40.

Richardson, J.C. & Alsup, J. (2015). Moving from the classroom to the keyboard: How seven teachers created their online teacher identities. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 16(1), 142-167.

Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 68-88.

Roby, T., Ashe, S., Singh, N., & Clark, C. (2013). Shaping the online experience: How administrators can influence student and instructor perceptions through policy and practice. The Internet and Higher Education, 17, 29-37.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (1999). Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 50–71.

Schutt, M., Allen, B. S., & Laumakis, M. A. (2009). The effects of instructor immediacy behaviors in online learning environments. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 10(2), 135-148.

Shea, P., Li, C. S., & Pickett, A. (2006). A study of teaching presence and student sense of learning community in fully online and web-enhanced college courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 9(3), 175−190.

Shea, P., Vickers, J., & Hayes, S. (2010). Online instructional effort measured through the lens of teaching presence in the Community of Inquiry Framework: A re-examination of measures and approach. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 11(3), 127-154.

Sheridan, K., & Kelly, M. A. (2010). The indicators of instructor presence that are important to students in online courses. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 6(4), 767-779.

Swan, K. (2002). Building learning communities in online courses: The importance of interaction. Education, Communication & Information, 2(1), 23-49.

Swan, K., Garrison, D. R., & Richardson, J. C. (2009). A constructivist approach to online learning: the Community of Inquiry framework. Information technology and constructivism in higher education: Progressive learning frameworks (pp. 43-57). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Swan, K., Shea, P., Richardson, J., Ice, P., Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2008). Validating a measurement tool of presence in online communities of inquiry. E-mentor, 2(24), 1-12.

Swan, K., & Shih, L. F. (2005). On the nature and development of social presence in online course discussions. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(3), 115-136.

Song, L., Singleton, E. S., Hill, J. R., & Koh, M. H. (2004). Improving online learning: Student perceptions of useful and challenging characteristics. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(1), 59-70.

Van de Vord, R., & Pogue, K. (2012). Teaching time investment: Does online really take more time than face-to-face? International Review of Research in Open & Distance Learning, 13(3), 132-146.

Wise, A., Chang, J., Duffy, T., & Valle, R. D. (2004). The effects of teacher social presence on student satisfaction, engagement, and learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 31(3), 247-271.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Final Coding Schema and Indicator Counts

Please see Supplementary files on the right side of the screen under the heading, Article Tools.