|

|

|

Kerry de Hart, Yuraisha Chetty, and Elizabeth Archer

University of South Africa

Open Educational Resources (OER) emerged within the context of open education which is typically characterized by the sharing of knowledge and resources and the exchange of ideas. Unisa as a mega open distance learning (ODL) university has publicly communicated its intention to take part in the use and creation of OER. As global and local university research on OER is limited, this prompted an investigation to gauge the uptake of OER at Unisa, by staff, with the purpose of institutional information gathering for decision making and planning in this area. During 2014, a survey was undertaken for this reason. The survey examined knowledge of OER, Intellectual Property (IP) Rights and Licensing, participation in OER, barriers to OER and OER in the Unisa context with a view to determining the stage at which the institution is in terms of adopting and engaging with the OER initiative. The results indicated that although there is knowledge and understanding of OER, this has not been converted into active participation. It further highlighted the barriers that are prohibiting the operationalization of OER and resulted in recommendations for planning and activities in respect of OER. The constructs investigated and the results thereof might not be generalizable to other contexts, although commonalities are likely. The insights should prove useful to a variety of contexts. The paper illustrates the need for institutions, irrespective of context, to take stock of the impact of initiatives and in this case evaluate how the institution and staff mature through various phases in the uptake of OER in order to guide effective planning, decision making and implementation.

Keywords: Open educational resources; OER, adoption; barriers; knowledge; Intellectual Property Rights; IP; institutional planning; open licensing

He who receives ideas from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine receives light without darkening me. Thomas Jefferson

Encapsulated in the above is the notion that education/expertise should be about sharing in a spirit of non-rivalry. At the heart of this is the principle of openness as a philosophy which underpins education. The World Wide Web has facilitated the exchanging of ideas and the sharing of resources by educators online (Ives & Pringle, 2013). Open Educational Resources (OER) are a fairly recent disruption, especially in South Africa but which have gained increasing attention and momentum in higher education across the world (McKerlich, Ives & McGreal, 2013). According to Mulder (2011), OER have become an unstoppable development since MIT started publishing educational resources online as OpenCourseWare (OCW) in 2001.

Allen & Seaman (2012), allude to the fact that formal OER initiatives can be traced to the late 20th Century through the developments in distance and online learning. The term Open Educational Resources (OER) was adopted at a UNESCO Forum on Open Courseware in 2002 to refer to the “open provision of educational resources, enabled by information and communication technologies, for consultation, use and adaptation by a community of users for non-commercial purposes” (UNESCO, 2002). The initial concept was crystallized further as follows:

...technology-enabled, open provision of educational resources for consultation, use and adaptation by a community of users for non-commercial purposes. They are typically made freely available over the Web or the Internet. Their principle use is by teachers and educational institutions to support course development, but they can also be used directly by students. Open Educational Resources include learning objects such as lecture material, references and readings, simulations, experiments and demonstrations, as well as syllabuses, curricula, and teachers guides. (Wiley, 2007)

Chetty (2011) refers to a report by the William and Hewlett foundation, a donor and major champion of openly licensed resources, wherein the notion of serving the public good and sharing knowledge is given expression. It is made explicit that “at the heart of the movement toward Open Educational Resources is the simple and powerful idea that the world’s knowledge is a public good and that technology in general and the World Wide Web in particular provide an extraordinary opportunity for everyone to share, use, and reuse knowledge” (Smith & Casserly, 2006). OER are the parts of that knowledge that comprise the fundamental components of education – content and tools for teaching, learning and research” (Atkins, Brown & Hammond, 2007).

Although there are many attempts at defining OER, as the concept matures, so the definitions have been shaped and have evolved. Unisa has adopted the UNESCO definition, in that OER are “teaching, learning and research materials in any medium, digital or otherwise, that reside in the public domain or that have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaption and redistribution with no or limited restrictions” (Atkins et al, 2007).

Licensing is the key component that sets OER apart from other resources and open licensing is currently dominated by Creative commons licensing regime (Butcher, nd) which provides a framework that sets out guidelines for sharing resources, namely:

At the core of open education is a commitment of open access to high quality education on a global scale as well as collaboration between higher education institutions (Phelan, 2012). The increasing number and range of OER initiatives and programmes globally is a testament to its recognized potential to change traditional modes of higher education provision and the development of study materials. These initiatives are furthermore enabled by the rapid rise of various information and communication technologies (ICTs) and software technologies, which are being employed in varying forms in teaching and learning practice, and have led to an increasing focus on virtual learning environments (VLEs). OER can be seen as the “emergence of creative participation in the development of digital content in the education sector” (OECD, 2007).

Today, there is an exceptional ability to contribute, share and leverage shared resources to educate (Bissell, 2009). The systematic integration into its courses of openly licensed content that is produced and made available openly, will enable higher education institutions to focus squarely on the provision of a much higher quality of service to students, that is not based exclusively or primarily on content delivery (Butcher, 2011). In this regard the amount of openly licensed content available for reuse and repurpose, is growing exponentially, already exceeding 250 million items in 2009 (Business Critical Learning, 2011).

Contextualizing OER within a distance education environment, it can be argued that OER initiatives’ aspiration to open access resonates strongly with the fundamental principle underpinning distance education. This principal is that spatial, geographical, economic and demographic boundaries must be reduced to facilitate and increase access to higher education.

This paper investigates the extent to which this institutional intent has been operationalized within an organization, taking stock of what is happening at the coal face of distance teaching and learning. It examines the factors inhibiting progress and highlights the type of support required to realize this commitment and both contribute and harness the potential of OER for the benefit of learners. Moreover the study endeavors to link the phase of adoption with respect to the OER initiative, to the interventions or actions that are required.

The creation and use of OER by staff is central to the OER initiative. Therefore it is essential to understand their attitude towards OER and to ascertain a baseline in order to monitor the institutional maturation with respect to the adoption of OER (Rolfe, 2012).

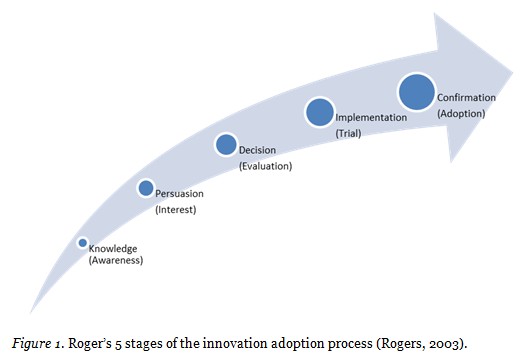

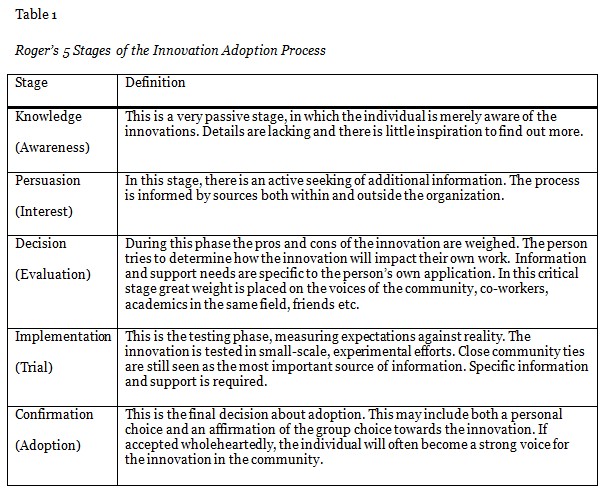

Any major disruption due to innovations such as OER, is a process, with staff and institutions alike moving through various stages of adoption. In this paper we will make use of the seminal work of Rogers: “Diffusion of Innovation” (Rogers, 2003) to conceptualize the various OER adoption stages. Rogers (2003) proposes that four main elements influence the spread of a new idea: the innovation itself, communication channels, time, and a social system. The innovation, in this case OER, must be widely adopted in order to self-sustain. This study thus provided an avenue to examine how Unisa staff members had matured through the various phases of adoption in order to facilitate appropriate support, communication and implementation efforts at each stage. These stages of innovation adoption would be appropriate across various contexts and provide a guideline for institutions to map their OER adoption trajectory.

The various stages in the innovation adoption process are associated with different informational and support needs. The first two stages, Knowledge and Persuasion are associated with awareness raising. In the case of OER, the institution plays a large role in sensitizing the community to the innovation and then providing more general information to support the growing knowledge. In the case of the OER implementation at Unisa, this was supported through internal communication efforts on the part of the institution as well as by providing repositories of relevant information.

The Decision and budding Implementation stage at Unisa has been supported by facilitating access to actual OER (e.g. on portals) to encourage the accessing of OER, initial efforts to use OER for teaching and learning purposes and concerns about barriers to implementation. It could also be characterized by efforts to engage with the barriers (perceived or real) and attempt to find workable solutions. Prohibitive barriers would need to be removed in order for the OER initiative to be fully operationalized.

The final stage of Confirmation will only be achieved with institution-wide roll out of OER, embedding OER into teaching and learning practice. This would require an optimal ICT infrastructure and support from teaching staff. It would therefore need to be preceded by actions to address various barriers. It would also be characterized by advocacy on the part of teaching staff who become the champions of the OER initiative, taking ownership and sustaining it. This study highlights the need to evaluate institutional initiatives in order to determine institutional maturity in terms of innovation adoption. Armed with this information, institutional efforts can be directed appropriately.

Higher Education and Training in South Africa includes undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, certificates, and diplomas, up to the level of doctoral degree. The country has 23 state-funded tertiary institutions (with 2 more currently being built). These consist of 11 universities, six universities of technology and six comprehensive institutions. Unisa is a comprehensive university offering a combination of academic and vocational diplomas and degrees (SouthAfrica.info). Until recently, Unisa was the only dedicated distance education institution in South Africa, however the White Paper for Post-School Education and Training specifically states that the Department of Higher Education and Training will encourage all universities to expand online and blended learning (DHET, 2014).

Governments can play an important role for setting the scene for innovation in terms of the policy environment that they create for higher education systems (COL, 2011). In South Africa, the White Paper for Post-School Education and Training (DHET, 2014) has added impetus to OER in South Africa, by contributing government policy commitment to the OER efforts that already exist in pockets within the country. The White Paper states that South Africa will create a post-school distance education landscape based on open learning principles. Further to this, the White Paper affirms that the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) will support efforts that invest in the design and development of high-quality learning resources that should be made freely available as open resources. The White Paper cites the key motivations for OER as the potential for improvements in the quality of education and reductions in cost (DHET, 2014).

The Commonwealth of Learning (2011) in its “Guidelines for Open Educational Resources (OER) in Higher Education” suggests that further to the role that the government plays in the OER arena, is the critical role that the institution will fulfill through support of their teaching staff. The first guideline given to an institution is that they should develop institutional strategies for the integration of OER (COL, 2011). Therefore the OER initiative at Unisa is based in an environment supported by both government and institutional management (Unisa has an approved OER Strategy and an OER coordinator appointed in the Pro Vice-Chancellor’s Office).

To provide further context for this article, it is necessary to briefly describe the specific institutional context within which we can locate the OER initiative under review. With specific reference to its magnitude and influence, the University of South Africa (Unisa) is a mega ODL university offering study opportunities to more than 400,000 students around the world. Qualifications from certificates to degree (up to doctorate level) are offered. During the 2012 academic year, registered students were studying towards 891 formal qualifications. Unisa is South Africa’s most productive university, accounting for 12,8% of all degrees conferred by the country’s 23 universities and universities of technology (Unisa Online, 2014a).

Unisa is also a university in the midst of transformation at several levels. Many historic processes, including the development of teaching materials, are being disrupted by advances in information and communication technology (ICT). Current teaching and learning practice at Unisa involves the use of blended techniques based on a predominantly paper based correspondence method that has been transferred to digital delivery via a Learning Management System. Study material development at Unisa is carried out by a team. The team consists mainly of academics and a curriculum designer. The team is supplemented from time to time as necessary by a librarian, graphic designer and language consultant. Going forward, Unisa has plans to convert to differing degrees of online teaching depending on the requirements of the content and the accessibility of the target population to the internet and even in some cases their access to devices. Further to these planned changes of increased delivery of courses in the online arena, the approval of the OER strategy in the midst of this transformation process, demonstrates that Unisa management has recognized that the vast quantities of teaching and learning content, especially openly licensed content, have the potential to contribute to the quality of the teaching and learning experience of its students.

The OER initiative at Unisa has been predominantly management led through the appointment of an OER coordinator and further to this the development and approval of an OER strategy. The emphasis of the OER strategy at Unisa is initially on the harnessing of available openly licensed resources, for the development of courseware. Through the OER strategy, the management of the institution has acknowledged that OER can no longer be considered as marginal, socially acceptable, ‘nice-to-have’ materials and that the use of OER needs to be integrated into mainstream institutional processes if their true potential is to be harnessed in the process of pedagogical transformation. In order for this high level strategic direction to be attained, OER integration needs to take root within the university processes and this was the crux of the matter being investigated in the baseline survey.

Based on a qualitative study carried out during 2011 at Unisa, the fears of respondents at that stage were that the successful implementation of an OER initiative would be plagued by issues relating to intellectual property, current workloads of academic staff and from an operational level, systems failures were also listed. From a strategic perspective, this earlier study of limited scope also highlighted the need for a clear policy, framework or strategy on OER (Chetty & Archer, 2011).

On the other hand there were also many enabling factors that were listed in this earlier study including the support of top management, the ODL environment, academic collaboration as well as the improvement of materials used for teaching and learning including the Africanization of resources (Chetty & Archer, 2011).

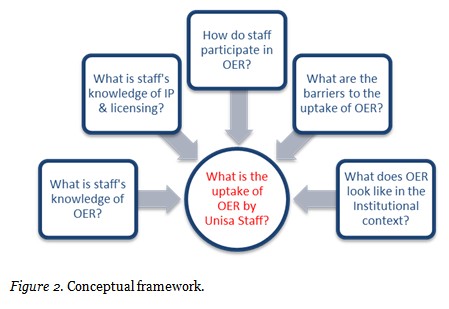

In light of the actions that have been undertaken by the university, the overarching research question was “What is the uptake of OER by Unisa staff?”. By answering this question, the maturity of the institution in terms of the implementation of OER can be measured. The survey questions covered five main areas in respect of OER, namely knowledge of OER, IP and licensing, participation in OER, barriers to participation in OER and OER in the Institutional context. This formed the conceptual framework of the research which informed a range of questions. The conceptual framework was guided by an extensive literature review on OER as well as the particular interests of Unisa as an ODL institution. In order to achieve the latter, a nuanced level of customization was necessary to ensure that the conceptual framework addressed the contextual peculiarities of the university.

The study was aimed at all academic staff (total population) and also targeted professional and administrative staff involved in teaching and learning or research issues (purposive sampling). The sample thus covered the first three Higher Education Management Information System (HEMIS) personnel categories of staff, including both permanent and contract staff with contracts of 1 year and longer:

This resulted in a sample of 3,800, with academic staff comprising 74,7%, professional 16,6% and administrative staff 8,7%. There were 483 respondents to the survey, constituting a 12,7% response rate. As this is a finite population, this provides an estimated sampling error of 4,3% (for p=50% assumed).

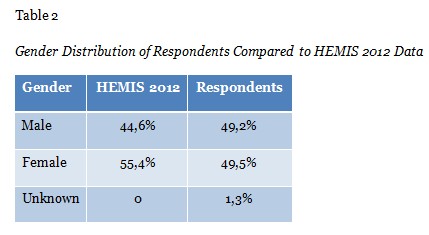

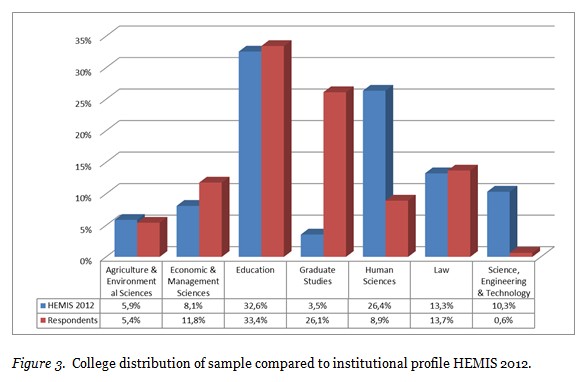

The respondents to the survey had a mean period of 6,1 years of employment at Unisa. All the South African regions were represented, with 76,2% of respondents residing in the Gauteng Province, reflecting the staff regional distribution of the institution. The gender and college profiles of respondents were further compared to the institutional profile as per the audited 2012 HEMIS staff data (see Table 2 and Figure 3) to determine representativeness.

It is evident that both genders were fairly equally represented in the sample with a slightly higher male representation than what is found in the general staff population. All the academic colleges in the institution were represented (see Figure 3). In terms of college representation, the College of Graduate Studies (a fairly small college) was over represented with the Colleges of Science, Engineering and Technology and Human Sciences being under represented.

The study was a follow-up to the 2011 OER study at Unisa. The original study aimed to establish the feasibility of initiating OER at Unisa. The study encompassed three phases, namely, a literature study to map the OER landscape, a review of OER initiatives, tools and resources and a feasibility study. The 2011 study formed part of the initial phase of the OER journey at Unisa. The feasibility phase was a precursor to the study being discussed in the article. The 2011 feasibility study consisted of hour-long semi-structured interviews with staff members who were either early-adopters of OER, or knowledgeable about OER which was at the time a fairly recent drive. The interviews focused on conceptual and definitional issues, benefits and challenges, different funding models, sustainability, key stakeholders, flagship projects and initiatives and OER practice at Unisa.

This article documents the next phase of studies on OER at Unisa. The latest study was informed by the 2011 studies, but is also acknowledgement that Unisa had matured beyond being only familiar to early-uptakers to being familiar to most staff. It was thus necessary to examine the level of uptake of OER throughout the entire Unisa community to determine how best to direct planning and efforts for the OER drive at Unisa. This investigation into the uptake of OER at Unisa took the form of a survey research design. Ethical clearance was sought and granted by the Unisa Senate Research and Innovation and Higher Degrees Committee before the research commenced. Staff were targeted through an online survey with quantitative (close-ended) and qualitative (open-ended) aspects.

The development and refinement of an appropriate instrument for Unisa’s context was guided by relevant literature on OER. Based on the literature, the survey focused on five main areas namely knowledge of OER, IP and licensing, participation in OER, barriers to participation in OER and OER in the Unisa context. As befits an OER study, the authors also examined existing instruments to see how these may be re-designed and re-used for the study. The survey instrument employed in an Australian research project on the “Adoption, use and management of Open Education Resources to enhance teaching and learning in Australia” (ALTC project, 2013) was identified as being useful in this regard. The instrument employed in the Unisa study thus incorporated many original items as well as expanded and refined items from the ALTC project. A few items were maintained to allow for comparison with the data from the ALTC project to enable benchmarking. The development of items and response categories were further guided by issues raised in the 2011 (Chetty & Archer) study as well as feedback and requests during engagement with staff during OER initiatives. The instrument attempted to include a wide variety of response categories, but allowed respondents to add additional responses not catered for in the instrument. Although the survey employed mainly closed ended questions for ease of administration and analysis, open-ended questions were included to provide staff with an opportunity to raise issues which may not have been captured in the provided options. The instrument was piloted prior to administration to improve the quality of the instrument by ensuring that questions were clear and unambiguous and that the logic and flow was appropriate.

The survey covered five main areas in respect of OER, namely: knowledge of OER, IP and licensing, participation in OER, barriers to participation in OER and OER in the Unisa context. The discussion of the results is organized according to these five main areas.

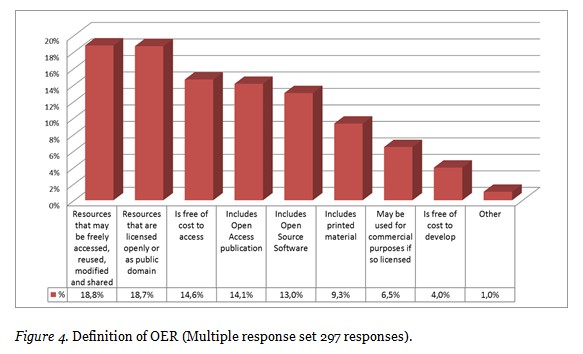

Seventy three per cent (73,5%) of respondents reported being aware of OER. The high level of awareness of OER was supported by the comprehensive understanding of what constitutes OER (Figure 4) demonstrated by participants. In terms of the initiative this bodes well for the institution in that staff members who are responsible for taking ownership and implementing have a good knowledge of the core of the initiative. Knowledge is the basis for institutional adoption with regards to the implementation of OER, as illustrated in the first stage of the innovation adoption process (Figure 2).

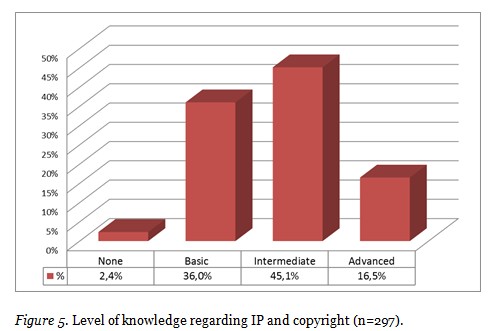

Respondents were asked to rate their level of knowledge regarding IP and copyright.

Survey participants were questioned about their knowledge of copyright in relation to the teaching materials that they developed at Unisa as part of their employment. The responses in terms of IP reveal a general lack of knowledge of intellectual property rights in respect of materials created by them as well as a lack of knowledge about open licenses.

Open licensing is the very aspect which sets OER apart and gives them potential. It is imperative that this knowledge is improved as it is a barrier which could prevent the implementation of OER or the conversion of knowledge of OER to obtain the actual benefit from the reuse, remixing and repurposing.

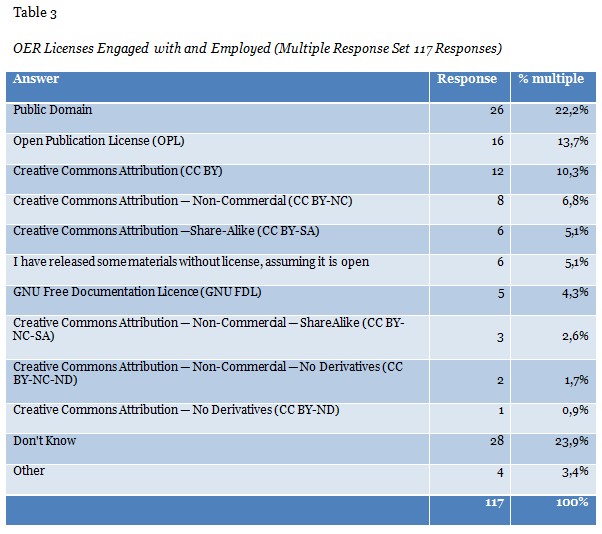

Further to this, the lack of knowledge of open licensing was evidenced in the fact that respondents reported that when they did engage with OER materials, they preferred less restrictive licenses, which are less complex to interpret (see Table 3).

The lack of knowledge of IP and specifically, open licensing, is a common thread in many studies on the adoption of OER (Allen & Seaman, 2014; Kursun, Cagiltay & Can, 2014; Bossu, Brown & Bull, 2012; Wild, 2011) and although the aim is not to turn authors into IP specialists there is a level of understanding that all creators of knowledge should have with regards to IP and related topics like open licensing.

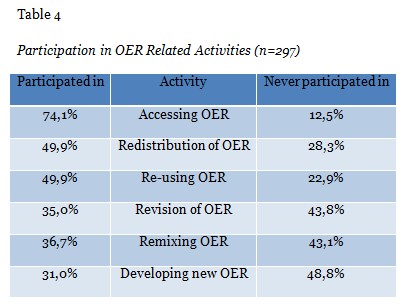

These questions measured how respondents had transferred their knowledge of OER into activities. This is an important indication of institutional readiness to eventually move up the OER adoption stages towards full adoption and commitment.

It is clear from the survey that there is a definite order within the frequency with which staff engages with OER related activities. Activities relating to the use of OER (accessing, redistributing and re-using) are far more frequent than activities relating to contributing to OER (revision, remixing, developing). This represents a healthy balance as the OER paradigm embraces collective production and sharing to harness efforts and avoid duplication. While it is important for academics to continue contributing to the global body of OER, the benefit of OER lies in the harnessing of existing resources rather than recreation.

Those involved in OER reported that they did so as they felt that it improved the quality of their teaching. Furthermore, a positive finding was that 73,4% of respondents indicated that they would like to be involved in OER activities in the future (with this item receiving over 30% of responses). This is supported by the responses to the position on sharing of own work, below. Participation in OER has two sides – creating resources to be shared with others and the reuse of resources which have been created by third parties, therefore participation in OER activities should measure both aspects.

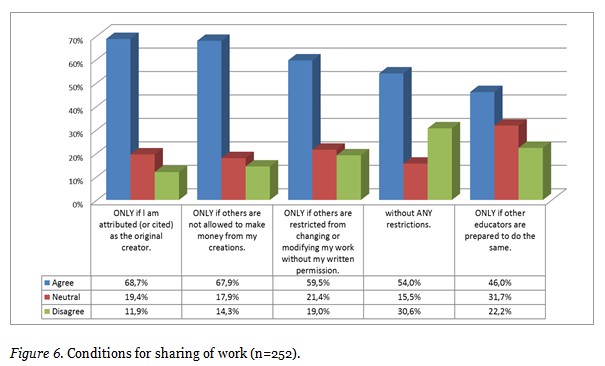

Respondents were generally amenable to sharing their work where they are attributed or if others were not allowed to make money from their creations. This indicates that the basic ethos for OER is in place, however once again the question of why this is not actively happening leads us to the barriers to OER and overcoming these, so that attitude can lead to operationalization. Other than the condition of attribution, the biggest reluctance to sharing of their own work was the concern that others may make money from it. Respondents were apparently confident about the quality of their offerings and were not concerned about their work being subject to scrutiny by others. This is in contrast to the earlier qualitative study carried out in the institution, where the attitude of academics to exposing their work to extensive peer review was regarded as a perceived barrier to OER implementation at the institution (Chetty & Archer, 2011). The attitudinal elements and dynamics which underpin the activity of sharing work are an important component of OER adoption, and might need to be interrogated in further research. If these aspects are ignored, it could hinder the progression of the institution towards full adoption and engagement of OER.

Respondents felt strongly that they would only use the work of others if they were allowed to adapt them for their own purposes and context. This provides an interesting comparison with the 59,5% of respondents who indicated that they only felt comfortable sharing their work if others were restricted from modifying their work without written permission. It’s also interesting to note one of the highest rated barriers to the use of OER are the fact that they are not created for specific contexts, yet respondents showed a high preparedness to adapting OER, suggesting that the barrier could be less of an issue than actually perceived.

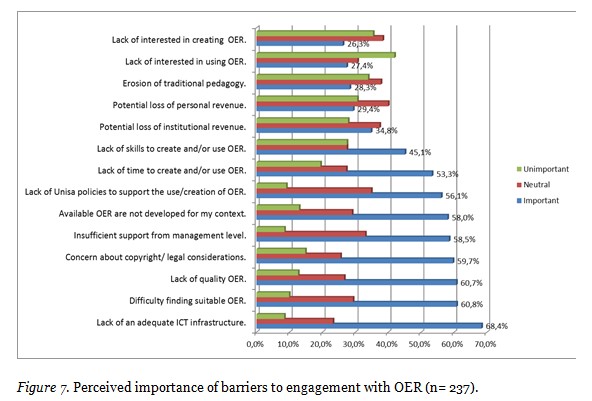

Based on literature, a list of potential barriers was provided, and respondents were requested to rate the importance of each barrier in their choice of engaging with OER. Participants could also select the other category and indicate additional barriers.

For the purpose of finding solutions to overcoming these barriers and in some cases perceived barriers, the authors were able to group the barriers into three groups, namely the intrinsic nature of OER, institutional infrastructure and personal attributes of staff. These will be discussed briefly in turn.

These barriers exist mostly due to the inherent nature of OER, for example, quality issues, format, and context. There is not much that the institution can do about these barriers, but in some instances training and support could mitigate some or parts of these barriers as they might be perceived rather than actual.

Findings indicate that 58% of respondents said that available OER are not developed for their context but in line with their attitude on the re-use of OER, parts of this barrier could be mitigated by adapting the resource for the intended context. The results also raised important questions about the location of suitable or high quality OER as well as how to determine if these were of a high quality once found. The finding that 60,8% said that suitable OER are difficult to find, points to a lack of knowledge about the possible sources of OER and suggests the need for training in where to find and access suitable or high quality OER. This could include training in identifying portals, repositories and other sources. The lack of quality OER as raised by 60,7% of respondents is a difficult barrier to remove, although it is suggested that a higher quality is expected of OER than of other resources. This barrier could also be addressed through appropriate training to assist academics in identifying OER of a high quality using various pre-determined criteria. These criteria could be developed by the teaching and learning committees across the various colleges within the institution. These quality OER could subsequently reside in a repository for use by the broader academic community within the institution. The processes for identifying quality OER and the development of relevant criteria to guide selection might vary across different subject matter and institutional contexts (Maloney, Moss, Keating, Kotsanas & Morgan, 2013). However, there might also be generic criteria which could be applicable across subjects and contexts.

These barriers are created due to institutional processes and policies and can be dealt with at an institutional level. Each institution will need to identify its own particular barriers in this category. The barrier that had the highest responses was the lack of adequate ICT infrastructure to support the creation and/or use of OER (68,4%). Many respondents also felt that there was a lack of policies to support the use or creation of OER (56,2%), and 48,4% reported that there was insufficient support from management. The last mentioned barrier is an interesting perception given that management has driven the OER strategy and associated institutional intention, suggesting their commitment. The fact that management are perceived as providing insufficient support would therefore warrant further probing, with a particular lens on how respondents understand “support” from management or what it means to them. Management’s efforts to drive the OER strategy may therefore not be interpreted as “support” by respondents. From the qualitative responses to the question of potential barriers, it is clear that support is required in terms of incentives – “no real incentive or recognition”, “tuition efforts are not linked to promotion, “extra time (Saturdays and Sundays) is rather used for research to ensure promotion”. Regarding the provision of training – “Lack of coaching in order to create due to scarce resources” or even the provision of skilled resources – “support especially skills”. Another area of support was seen to be the provision to make time to find, use and create OERs –

“In order to make use of OERs, and perhaps more importantly, to contribute to them in terms of both teaching & learning and research, training needs to be given. As with so many other projects that come to life in the University, inadequate training and time to acquaint oneself with new programmes is provided. Thus, one is simply expected to become part of something of which one has very little knowledge.”

“Finding time to participate and learn”

While a further probing falls out of the scope of this research, the study could be expanded in future to explore such aspects.

These barriers relate directly to the respondent and can be overcome through professional development and planning. The respondents rated their concern about copyright and legal considerations as the most important personal barrier (59,7%), while not having sufficient time available to create and/or use OER was rated second (52,3%). A lack of skills was rated as the third most important personal barrier to the creation and/or use of OER (45,1%). As licensing is a key element of OER, it was expected that it would be one of the predominant barriers (Bissell, 2009). Interestingly, the loss of personal revenue (29,4%) and not being interested in using (27,4%) or creating (26,3%) OER were not as highly rated in terms of being important barriers to OER. This indicates a positive attitude towards the creation and use of OER by staff.

It is interesting to note that even though South Africa is considered a developing economy, similar barriers exist in Unisa to those that have been identified in previous research (Pawlowski, 2012), even in more developed economies. Common barriers to the adoption of OER include lack of legal and intellectual property rights, lack of time, finding appropriate OER as well as the question of the quality of OERs (Pawlowski, 2012; Abeywardena, Dhanarajan & Chan 2012; Allen & Seaman, 2012). Therefore, the findings of this study in relation to the barriers to OER are clearly relevant to other contexts and are not merely context-specific.

The barriers pertaining to the institutional infrastructure and the personal attributes of staff will also relate very closely to the maturity of the institution in relation to its journey to full OER adoption.

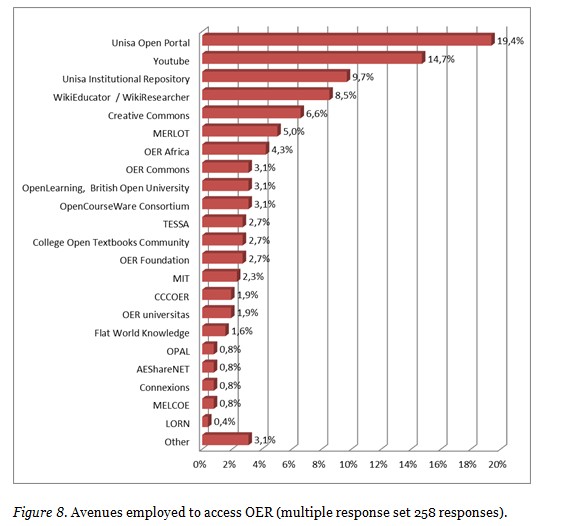

Almost a quarter (22,0%) of respondents, reported that they had been introduced to OER through Unisa’s internal communications, while 15,0% stated that Unisa colleagues had introduced them to OER. Staff reported the most popular avenue for accessing OER materials as the Unisa Open Portal (http://unisa.ac.za/oer), while the Unisa institutional repository was indicated as the third most popular avenue (see Figure 8). The fact that both Unisa’s internal communications and the Unisa Open Portal are shown to be effective in respect to advocating OER suggests that efforts to communicate about OER can continue to make use of these platforms, amongst others. The popularity of these avenues in many cases above huge global OER collections such as those hosted by Youtube, WikiEducator/WikiResearcher and Creative Commons speaks to the effectiveness and practicality of these institutional initiatives.

Earlier findings revealed discontent with aspects of the institutional infrastructure, including policies and an inadequate ICT infrastructure. The popularity of the portal which is a part of this infrastructure could point to the success of institutional communication and advocacy efforts and respondents’ willingness to use what was available to them. This does not detract from their general dissatisfaction with the ICT infrastructure. Future research could perhaps attempt to unpack exactly what about the ICT infrastructure was problematic to avoid confusion and generalizations.

The research further explored levels of commitment among staff to OER as a key initiative.

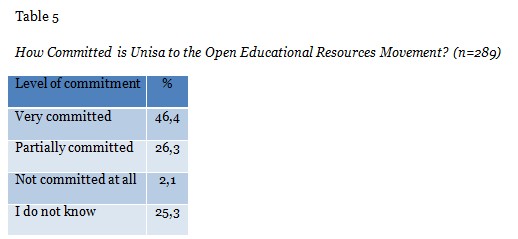

Most respondents (72,0%) reported being aware of Unisa OER projects and a similar percentage (72,7%) stated that they felt that Unisa was committed to OER. Only 2,1% felt that Unisa was not committed at all.

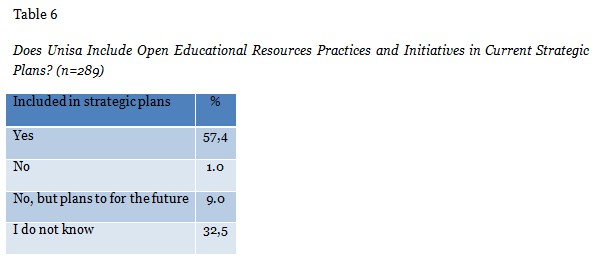

Findings revealed that 57,4% of respondents agreed that Unisa includes OER practices and initiatives in current strategic plans, while a third of the respondents (32,5%) did not know if this was the case. In light of the fact that these respondents might not engage with internal communications, it was suggested that other forms of advocacy may be necessary.

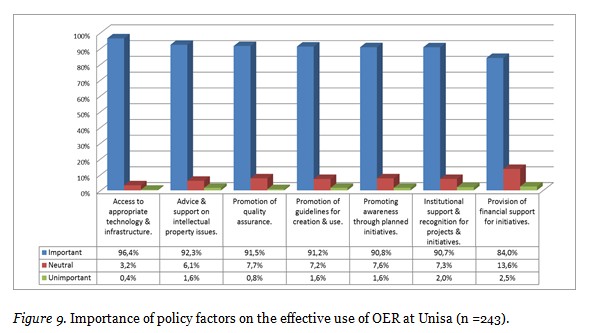

It is clear from the survey that the incorporation of OER into all relevant policies and processes will be an enabling factor and should be given attention. All seven factors listed in the survey were deemed important for the effective use of OER at Unisa. From the responses obtained, it is evident that policy will need to address all of them, namely, access to appropriate technology and infrastructure, advice and support on intellectual property issues, promotion of quality assurance, promotion of guidelines for creation and use, promoting awareness through planned initiatives, institutional support and recognition for initiatives and provision of financial support for initiatives (see Figure 9).

The highest value of OER was placed on the potential to increase collaboration within Unisa and internationally. Over 80,0% of respondents also agreed that OER: are well aligned with academic traditions of sharing knowledge; are beneficial to learners; have the potential to raise the international profile of Unisa; and have the potential to save development time. Over 70,0% of respondents placed value on OER for Unisa in that they: help enhance the quality of teaching and learning; help reduce the cost of development; are a good marketing strategy to showcase Unisa; and can improve the quality of learning materials.

The highest rated statement (93,9%) was the observation that, in order to stimulate the use of OER, specific technological infrastructure was required. Added to this was agreement that specific skills support (87,2%) and training (87,2%) was required in the use of OER. In line with the findings that active participation in the re-use of OER is not very high at the institution, these aspects will need to be given attention. Furthermore, 78,2% of respondents agreed that the mainstream adoption of OER will be challenging for the institution and 84,9% agreed that the use of OER will lead to new pedagogical practices. In response to the latter, given that the use of OER is not yet mainstreamed at the institution and widely incorporated into teaching and learning practices, it is not surprising that their use is seen as leading to “new” pedagogical practices.

This study was aimed at providing baseline data on the uptake and current success of mainstreaming OER at an open distance learning institution with a view to determining the maturity of the staff in adopting and engaging with the OER initiative. The results of this study were instructive and provided pointers to the institution with regard to where the majority of staff are located in terms of the five adoption stages. Data revealed that as an institution there has been a progression through the stages achieving greater OER adoption, but that this has been a slow process. In particular, it confirmed that while some Innovators and Early Adopters have moved towards the Decision and Implementation stage, the majority of Unisa staff are still grappling with the Persuasion and Decision stages. It will therefore still be some time until a critical mass of adopters is achieved for OER at Unisa, ensuring sustainability for the initiative.

The study provided a gauge of the effectiveness of current OER initiatives, strategies and efforts at the institution. From the data it is evident that awareness and knowledge of OER is quite high (73,5%) among staff. This indicates some success for the OER efforts at the institution and signals that this institution has reached a level of maturity with regards to OER adoption, where the focus can shift from awareness towards increasing the adoption of and engagement with OER.

Increasing engagement is, however, a multi-pronged process requiring institutional intervention to address barriers such as insufficient ICT infrastructure and policy issues. Training is also required to provide staff with the skills and knowledge to confidently engage with IP issues. The recommendations emanating from the study have interdependencies but will assist in prioritising activities in terms of OER coordination to ensure that the important foundation achieved in terms of knowledge and awareness of OER is built on through the operationalizing and implementation of OER in terms of the OER strategy. The fact that the study was undertaken in an open distance learning context does not make the findings or recommendations less applicable to contact institutions.

The study while undertaken within a particular context has relevance to institutions in other contexts and the broader higher education sector generally. In particular, it highlights the need to monitor institutional initiatives to evaluate the impact they are having and ascertain where effort should be directed. Any major shift, due to disruptive innovations such as the OER movement, is a process, with the staff and institution moving through various phases of growth and maturity (Wild, 2011). Awareness of how staff are progressing through the various stages of adoption of an innovation (Rogers, 2003) such as OER provides a structure against which to measure progress and plan communication and intervention. The data is crucial for evidence-based decision making, planning and policy implementation.

Aberywardena, I.S., Dhanarajan, G., & Chan, C.S. (2012). Searching and locating OER: Barriers to the wider adoption of OER for teaching in Asia. Proceedings of the Regional Symposium on Open Educational Resources.

Aitkens, D.E., Brown, J.S. & Hammond, A.L. (2007). A review of the Open Educational Resources (OER) Movement: Achievements, Challenges, and New Opportunities. Report to the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Allen, I.E. & Seaman, J. (2012). Growing the Curriculum: Open Education Resources in U.S. Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/growingthecurriculum.pdf

Allen, I.E. & Seaman, J. (2014). Opening the Curriculum: Open Education Resources in U.S. Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/oer.html

ALTC project. (2013). OER in Australia - WikiResearcher. Retrieved from http://wikiresearcher.org/OER_in_Australia

Bissell, A.N. (2009). Permission granted: Open licensing for educational resources. Open Learning, 24(1), February 2009, 97-106.

Bossu, C. Brown, M. & Bull, D. (2012). Do Open Educational Resources represent additional challenges or advantages to the current climate of change in the Australian higher education sector? Conference proceedings. Ascilite 2012. Retrieved from http://eprints.usq.edu.au/23472/2/Bossu_Brown_Bull _ASCILITE2012 _PV.pdf

Business Critical Learning (2011, April 6). LS2011: Open Educational Resources. Retrieved from http://businesscriticallearning.com/ls2011-open-education-resources/

Butcher, N. (nd). OER dossier: Open Educational Resources and Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/OER_Open_Educational_Resources_and_Higher_Education.pdf

Butcher, N. (2011). A Basic Guide to Open Educational Resources (OER). Commonwealth of Learning and UNESCO. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/PublicationDocuments/Basic-Guide-To-OER.pdf\

Commonwealth of Learning. (2011.) Guidelines for Open Educational Resources (OER) in Higher Education. Commonwealth of Learning: Vancouver.

Chetty, Y.B. (2011). Briefing on Open Educational Resources. DISA: Pretoria.

Chetty, Y.B & Archer E. (2011). Open Educational Resources (OER) feasibility study. DISA: Pretoria

Department of Higher education and training (2014). White Paper for Post-School Education and Training. Building an expanded, effective and integrated post-school system. DHET: Pretoria.

Ives, C. & Pringle, M.M. (2013). Moving to Open Educational Resources at Athabasca University: A case study. IRRODL, 14(2).

Kursun, E. Cagiltay, K & Can, G. (2014). An Investigation of Faculty Perspectives on Barriers, Incentives, and Benefits of the OER Movement in Turkey. IRRODL, 15(6), December 2014.

Maloney, S., Moss, A., Keating, J., Kotsanas, G., & Morgan, P. (2013). Sharing teaching and learning resources: Perceptions of a university’s faculty members. Medical Education, (47), 811-819.

McKerlich, R., Ives, C. & McGreal, R. (2013). Measuring Use and Creation of Open Educational Resources in Higher Education. IRRODL, 14(4), October 2013.

Mulder, A. (2011, September 11). Open Educational Resources and the Role of the university. EDUCAUSE review online. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/open-educational-resources-and-role-university.

OECD. (2007). Giving knowledge for free: The emergence of Open Educational Resources. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pawlowski, J.M. (2012). Emotional Ownership as the Key to OER Adoption: From Sharing Products and Resources to Sharing Ideas and Commitment across Borders. EFQUEL Innovation Forum, Sep. 2012.

Phelan, L., (2012). Politics, practices, and possibilities of open educational resources. Distance Education, 33(2), August 2012, 279 – 282.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations, 5th Edition. (p. 512).

Rolfe, V. (2012). Open educational resources: staff attitutdes and awareness. Research in Learning Technology, 20, 2012.

SouthAfrica.info. Retrieved from http://www.southafrica.info/about/education/education.htm

Smith, M.S., and Casserly, C.M. (2006). The promise of Open Educational Resources. Change, 38(5), 8-17.

UNESCO. (2002). Forum on the impact of open courseware for higher education in developing countries. Final Report. UNESCO. Paris.

UNESCO & Commonwealth of Learning. (2011). Guidelines for open educational resources (OER) in higher education. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/resources/publications/Pages/detail.aspx?PID=364

Unisa Online (2014a). Student success. Accessed from http://www.unisa.ac.za/Default.asp?Cmd=ViewContent&ContentID=15928.

Unisa Online (2014b). Teaching. Accessed from http://www.unisa.ac.za/Default.asp?Cmd=ViewContent&ContentID=18121

Wild, J. (2011). OER Engagement Study. Promoting OER Reuse Among Academics. Score Research Report.

Wiley, D. (2007). On the sustainability of open educational resource initiatives in higher education. France: OECD publishing.

© De Hart, Chetty and Archer