|

|

|

Scott Bulfin, Luci Pangrazio, and Neil Selwyn

Monash University, Australia

One notable ‘disruptive’ impact of massive open online courses (MOOCs) has been an increased public discussion of online education. While much debate over the potential and challenges of MOOCs has taken place online confined largely to niche communities of practitioners and advocates, the rise of corporate ‘xMOOC’ ventures such as Coursera, edX and Udacity has prompted popular mass media interest at levels not seen with previous educational innovations. This article addresses this important societal outcome of the recent emergence of MOOCs as an educational form by examining the popular discursive construction of MOOCs over the past 24 months within mainstream news media sources in United States, Australia and the UK. In particular, we provide a critical account of what has been an important phase in the history of educational technology—detailing a period when popular discussion of MOOCs has far outweighed actual use/participation. We argue that a critical analysis of MOOC discourse throughout the past two years highlights broader societal struggles over education and digital technology—capturing a significant moment before these debates subside with the anticipated normalization and assimilation of MOOCs into educational practice. This analysis also sheds light on the influences underpinning how many people perceive MOOCs thereby leading to a better understanding of acceptance/adoption and rejection/resistance amongst various professional and popular publics.

Keywords: MOOC; higher education; education reform; elearning; discourse; news media

One of the most notable ‘disruptive’ impacts of massive open online courses (MOOCs) to date has been the increased public discussion of online education and e-learning. Of course, much debate over the rights and wrongs of MOOCs has taken place online (through blogs, Twitter and other social media platforms), but thereby confined largely to niche communities of likeminded education technology practitioners and advocates. However, the rise of corporate ‘xMOOC’ ventures such as Coursera, edX and Udacity has prompted popular mass media interest at levels not seen with previous educational innovations. Indeed, perhaps the most tangible impact of MOOCs to date has been their stimulation of an unprecedented volume and urgency of debate about higher education in the digital age.

This article (and the broader MRI-funded project that it provides a ‘first glimpse’ of) addresses this important societal outcome of the recent emergence of MOOCs as an educational form—examining the popular discursive construction of MOOCs over the past 24 months within mainstream news media sources. Such an approach provides a counterpoint to many of the other research articles in this Special Issue. In particular, this article provides a critical account of what has been an important phase in the history of educational technology—detailing a period when popular discussion of MOOCs has far outweighed actual use/participation. As such, a critical analysis of MOOC discourse throughout the past two years highlights broader societal struggles over education and digital technology—capturing a significant moment before these debates subside with the anticipated normalization and assimilation of MOOC-like online education, in whatever form, into educational practice. This analysis also has a practical benefit of shedding light on the influences underpinning how many people perceive MOOCs—leading to a better understanding of acceptance/adoption and rejection/resistance amongst various professional and popular publics.

In terms of theoretical approach, this project is situated within the tradition of critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, 2003), and is therefore concerned primarily with the ways in which the discourses around MOOCs reproduce and/or disrupt social and political inequalities within higher education. This approach is well-suited to testing the ideologies and values that have surrounded the recent rise of MOOCs—especially in terms of claims related to: the democratizing of educational opportunity; the challenging of institutional monopolies within higher education; and the benefits/limitations of a diversity of educational provision. As Taylor (2004) argues, taking this approach is of particular value in documenting multiple and competing discourses within education, in highlighting marginalized and hybrid discourses, and in documenting discursive shifts over time. Given the fast-changing and complex nature of the development of MOOCs over the past few years (e.g., from the connectivist model of the ‘cMOOC’ to the corporate and institutionally-focused model of ‘xMOOCs’), a discourse analysis perspective can provide a much-needed socio-political analysis to the prevailing claims and counter-claims currently surrounding this area of educational activity.

Against this background, the remainder of this article will explore the following research questions:

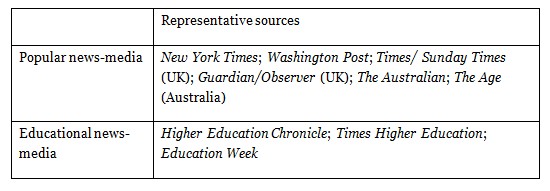

The article adopts a discourse analysis approach to investigating these questions – drawing on established methodologies from social linguistics and the social sciences that have also begun to be used increasingly in educational research (see Rogers et al., 2005 for an overview). First, a large-scale corpus of text was established encompassing news media stories produced between January 2012 and December 2013 in the following two areas of English language discourse production:

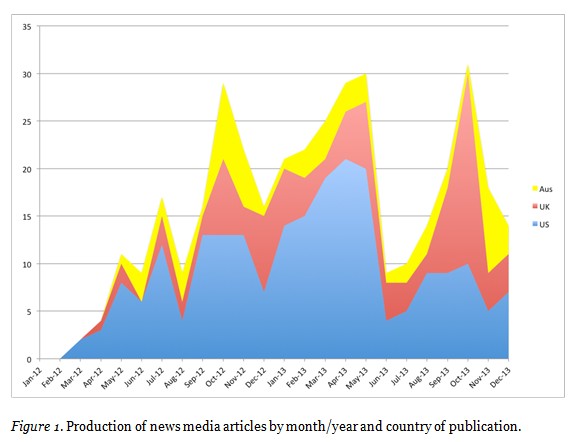

The six popular news-media sources were selected deliberately to include the ‘newspapers of record’ from the US (New York Times), UK (Times) and Australia (Australian), alongside corresponding national titles in each country which have also focused on educational and technology issues (Washington Post, Guardian, Age) . Similarly the three specialist educational news-media titles were selected due to their long-standing reputation as authoritative sources on higher education (Chronicle, Times Higher Education), and their sustained featuring of MOOC-related reports over the past three years (Education Week). Interrogations of these sources through the Factiva databases with the search terms ‘MOOC or Udacity or edX or Coursera’ returned 457 different articles (see Figure 1 for a breakdown of these data by month and country of origin). All text was collated and categorized using the N*VIVO qualitative data analysis application.

The initial phase of data analysis reported upon in this article used a frame analysis of MOOC discourses (Gerhards, 1995; Goffman, 1975; MacLachlan & Reid, 1994). This aimed to analyze the ‘tone’ of the media discourse on MOOCs and ‘sketch’ how MOOC issues are viewed. The data reported on in this article relate to two elements of each newspaper article. First, is the headline attached to the article—usually written by a newspaper’s sub-editor and intended to provide ‘initial summaries of new texts and foreground what the producer regards as most relevant and of maximum interest or appeal to readers’ (Brookes, 1995, p. 467). In this sense, ‘headlines help readers construct an ideological approach to the content of the article … provid[ing] the dominant image of a given event and the way the event is apt to be stored in the mind of readers’ (Johnson & Avery 1999, p. 452). In total 371 headlines were specifically related to MOOCs (as opposed to generic titles such as ‘News In Brief’) and coded accordingly. Second, is the initial orientating description offered within the main text of the news article (if at all) of what a ‘MOOC’ is. In total, 281 such descriptions were identified and coded accordingly. These were typically one or two lines, with an average of 14.53 words per excerpt. Focusing on these two integral elements of each article allows us to identify two important meaning making functions—the ‘what is?’ question (contained in the in-text description) and the ‘so what?’ question (contained within the headline).

Our analysis of these texts was both quantitative and qualitative in nature, thereby aiming to identify the overall patterns of how MOOCs have been interpreted by different sources. Particular attention was paid to identifying patterns between type of discourse and the characteristics of the sources involved (i.e., type of publication, institutions/individuals that are represented and so on.). A further aim of this analysis was to cross-tabulate specific discursive themes/concerns with different types of institution/stakeholder/country—thereby beginning to explore the patterning of MOOC discourses across different sub-groups and contexts.

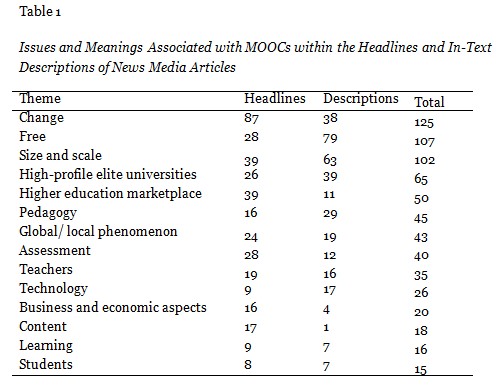

The analysis and coding of the headline and definition texts resulted in 14 distinct themes—the nature and prevalence of which is described in Table 1 and below.

As the data in Table 1 show, the most prevalent definitions and justifications related to the following four themes: i) MOOCs as a source of change; ii) MOOCs as a source of free education; iii) the size and scale of MOOC programs; and iv) the MOOCs of high-profile elite universities.

The most prevalent meaning within the data was that of a vague sense of inevitable, substantial ‘change’ (n=125). MOOCs were described as a ‘digital change agent’ (Chronicle of HE, 4.3.2013) and source of ‘creative destruction’ (Washington Post, 20.5.2013). A key theme here was disruption of the established order—‘the education world has been thrown into disarray’ (Sunday Times, 1.12.2013), with MOOCs ‘disrupting centuries-old models’ (Chronicle of Higher Education, 28.10.2013). These were courses that marked a new educational direction—‘path breaking’ (Chronicle of HE, 25.3.2013) and representing ‘learning’s new path’ (Australian, 17.8.2013). The momentum of these changes was described in forceful terms as a ‘revolution’ (New York Times, 16.5.2012), ‘juggernaut’ (Australian, 7.11.2012) and ‘phenomenon’ (Washington Post, 29.8.2013). Throughout all these descriptions was an unspecified inference that MOOCs were altering substantially the structures of higher education. The MOOC was announced as ‘game-changing’ (Times Higher Ed, 20.12.2012), and as a ‘game-changer’ (New York Times, 17.7.2012) that ‘changes the game’ (Age, 5.6.2012).

The importance of these changes was sometimes described as marking a distinctive point in time – signifying ‘higher education in the digital age’ (Times Higher Ed, 6.6.2013), or an ‘era of free courses’ (Chronicle of HE, 1.10.2012). As the New York Times (4.11.2012) put it, 2012 was ‘The Year of the MOOC’. On occasion such claims of history-in-the-making were tempered with a knowing nod towards the prevailing hyperbole. The topic was acknowledged as ‘the current buzz in higher education’ (New York Times, 15.10.2013); a ‘bandwagon’ (Chronicle of HE, 3.9.2012) and source of ‘irrational exuberance’ (Washington Post, 27.1.2013). As this awkwardly self-aware description put it,

MOOCs. It sounds like a hipster street wear brand, but the acronym stands for massive online open courses—and they are flavour of the month. Just like new street wear, they are seen as the next big thing that everyone will want to have. (Age, 28.8.2012)

Beyond this apparent timeliness, the imagined origins of the change associated with MOOCs were divided along two distinct lines. Crudely, the origin stories associated with MOOCs followed narratives concerned with either ‘science’ or ‘nature’. In the former sense were portrayals of MOOCs as a product of science-like development and innovation. MOOCs were described on numerous occasions as ‘experiments’—that is, ‘an important new experiment in higher education’ (Washington Post, 8.10.2013); ‘somewhat experimental’ (Australian, 6.3.2013); and ‘radical experiments in higher education’ (Times, 17.10.2012). These were ‘wildly innovative offerings’ (Washington Post, 10.05.2012) that stemmed from ‘the soul of invention’ (Chronicle of HE, 25.3.2013). Udacity was introduced as ‘an internet platform created by two Stanford University scientists’ (Times Higher Ed, 17.7.2012)—a feat of invention akin to other ambitious innovations in science and engineering—‘from self-flying helicopters to classrooms of the future’ (Chronicle of HE, 1.10.2012).

These stories of scientific invention and innovation were accompanied by contrasting construction of MOOCs as natural phenomena. Here, parallels were often drawn with forces of nature—a ‘campus tsunami’ (New York Times, 4.5.2012), ‘an avalanche’ (Guardian, 30.4.2013) and ‘an online wave’ (New York Times, 23.9.2013). The capacity of MOOCs for change and renewal was sometimes framed in material and elemental terms—‘instruction for masses knocks down campus walls’ (New York Times, 5.3.2012); ‘MOOCs break the mould’ (Australian, 20.2.2013); ‘MOOCs knocking at the foundations’ (Australian, 20.2.2013); or ‘MOOCs Sends Shock Waves’ (Chronicle of HE, 14.3.2013). On occasion, this association with nature was imagined in bestial rather than elemental terms. MOOCs were ‘a new beast in the academy’ (Times Higher Ed, 6.12.2012) and somewhat fancifully a ‘disruptive dragon’ (Times Higher Ed, 6.12.2012). The implication of such evolution was the eventual distinction of previous forms of education: “The MOOC is the latest stage in a series of technological changes that have made life easier for students and their teachers but have made the traditional lecture look ever more of an endangered species” (Times Higher Ed, 4.10.2012).

The second prominent meaning associated with MOOCs was the more uniformly expressed characteristic of being ‘free’ (n=107). This oft-repeated term was clearly being used in a monetary rather than an emancipatory sense (i.e., ‘free beer’ rather than ‘free spirit’). Thus the most prominent feature of the in-text descriptions (79 of the 281 coded descriptions) was the ostensibly no-cost nature of MOOCs. These were programs that offered university education of ‘the kind once available only to students paying tens of thousands of dollars in tuition at places like Harvard and Stanford’ (Chronicle of HE, 3.6.2013). In this spirit, MOOCs were presented as ‘free education’ (Guardian, 4.12.2012), ‘a new kind of free class’ (New York Times, 21.8.2012), and as an ‘undergraduate-level courses without any fees’ (Times, 17.7.2012). The concept of university-level education being offered to students ‘at no charge’ (Washington Post, 4.11.2012) was generally described in incredulous tones, but also on occasion as a logical development in financially constrained times. As one Washington Post (5.9.2013) headline put it, ‘The Tuition is Too Damn High, Part IX: Will MOOCs save us?’.

As befits the opening word of the acronym, a third defining feature of MOOCs was their size and scale (n=102). Notable throughout the data was news media’s continual attempts to synonymize the concept of ‘massive’. Thus MOOCs were introduced as ‘huge’ (Chronicle of HE, 2.7.2012; Times, 20.6.2013); ‘giant’ (New York Times, 11.3.2013); ‘mass’ (Australian, 8.7.2012) and ‘mega’ (Chronicle of HE, 17.9.2012). This was education on a ‘very large-scale’ (Australian, 27.11.2012) and reaching ‘a very large number of people’ (Washington Post, 28.8.2013). Indeed, the exact quantification of this ‘mass engagement’ (Times Higher Ed, 18.10.2012) varied considerably between sources. The Chronicle of Higher Education (11.6.2012; 1.10.2012; 8.5.2013) was keen to talk about ‘thousands of students’. On other occasions these numbers increased to ‘tens of thousands of people’ (Washington Post, 24.8.2013); ‘courses with more than 100,000 people enrolled’ (Chronicle of HE, 1.10.2012); and more specifically ‘150,000 students’ (New York Times, 22.7.2012). Less precisely was talk of ‘millions of learners around the world’ (Washington Post, 3.5.2012), and even less probably estimates of ‘opening higher education to hundreds of millions of people’ (New York Times, 17.7.2012).

These increased volumes of learners were portrayed consistently as a vast—if not unlimited—expansion of what was previously a constrained process. MOOCs were celebrated for their ‘unlimited capacity for enrolment’ (Chronicle of HE, 22.10.2012) and ‘unfettered’ nature (Chronicle of HE, 8.8.2013). This expansion was typically associated with various economies of scale—facilitating courses that were somehow able to ‘harness the power of their huge enrolments’ (New York Times, 20.11.2012). In particular, descriptions in the mainstream newspapers highlighted the democratizing nature of MOOCs. As one New York Times (5.3.2012) article put it, ‘welcome to the brave new world of Massive Open Online Courses—known as MOOCs—a tool for democratizing higher education’. These were courses ‘open to all’ (New York Times, 15.7.2013), ‘freely available to anyone who wants to use them’ (Guardian 23.10.2012), or at least ‘anyone with an Internet connection’ (New York Times 30.4.2013).

Another defining issue prominent throughout the data (n=65) was the notion that MOOCs were the province of high-profile elite universities. The MOOCs referred to within the majority of articles were being developed by ‘leading unis’ (Guardian, 18.6.2013); ‘top universities’ (New York Times, 18.4.2012; Times, 16.9.2013; Times Higher Ed, 17.7.2012); ‘world-leading universities’ (Age, 2.10.2012) and ‘leading academic brands’ (Washington Post, 4.5.2012). MOOCs were described as being the preserve of ‘elite’ (Washington Post, 2.5.2013; 4.11.2012; 7.2.2013); ‘prestigious’ (Times Higher Ed, 21.3.2013; 10.5.2012; Chronicle of HE, 18.6.2012); ‘stellar’ (Australian, 8.11.2013) and ‘star’ institutions (Times Higher Ed 20.12.2012; Chronicle of HE 5.11.2012). Despite their mass nature, MOOCs were certainly not the realm of the ordinary.

A recurring theme within US news media portrayals of this exceptionalism was the inference that the development of MOOCs was driven by elite American universities—as the Chronicle of HE (1.10.2012) put it, ‘led by some of the nation’s most prestigious research universities’. Alternatively, Australian news media were more likely to stress the involvement of Ivy League universities. Here, MOOCs were positioned as ‘an online phenomenon emanating from the US’s Ivy League’ (Australian, 17.8.2013), with this specific association adding luster to online learning: ‘online courses winning prestige—Ivy League lends knowledge’ (Australian, 4.7.2012). This pride in the Ivy League was conveyed in a few US commentaries. Indeed, the Washington Post (10.5.2012) went as far as to equate MOOCs with recent social uprisings in north Africa and the Middle East—‘what some have referred to as the “Ivy League Spring”’. Thus a telling distinction emerged in these descriptions between institutions that were ‘top dogs’ (Times Higher Ed, 20.9.2012) and ‘big fish’ (Times Higher Ed, 26.9.2013) as opposed to the ‘small fry’ (Times Higher Ed, 26.9.2013).

As can be seen from Table 1, a number of less prevalent meanings and issues were also apparent within the text corpus. First amongst these were a set of issues relating to the higher education marketplace (n=50) and competition between education providers. These descriptions tended to focus on the role of MOOCs in reordering the higher education marketplace. On one hand, universities’ involvement in MOOCs was presented as a prerequisite for remaining a competitive higher education provider—as the Guardian (28.10.2012) put it, ‘traditional universities have felt the need to cover their internet flank by offering courses online’. Conversely, MOOCs were contributing to an uncertain ‘future in flux: the battle for the online market is just beginning’ (Times, 17.10.2012). Flux or not, most of these stories described already successful universities extending their market reach. MOOCs were described as an additional opportunity for universities to extend their ‘export strategy’ (Australian, 1.8.2012) and ‘expands slate of universities’ (New York Times, 19.9.2012). Thus rather than disrupting the pre-existing market dynamics, MOOCs tended to be defined as augmenting rather than altering patterns of market success. As the Australian (6.6.2012) explained, ‘MOOC is not a direct competitor. It is a new kind of product. It could become a second line of credential’. Similarly, as one UK newspaper described, ‘for universities, MOOCs act like virtual shop windows to drive paying students through their doors’ (Sunday Times, 1.12.2013). MOOCs were seen as offering an additional gateway into ‘full’ and more traditional forms of higher education—‘taster’ courses (Australian, 31.10.2012; 27.11.2013).

Second in terms of less prominent issues were those related to pedagogy (n=45). When pedagogic issues were evoked, the texts focused largely on the modes of delivery used in MOOC-based teaching and learning. Here MOOCs were most commonly described using the typical language of university tuition—that is, as ‘online classes’ (New York Times, 18.9.2013); the ‘online lecture’ (Washington Post, 2.5.2013); ‘online tutorials’ (Times, 8.9.2012); the ‘virtual seminar’ (Education Week, 6.2.2013). When not framing MOOCs in these familiar terms, articles and headlines were pointing to another defining pedagogic feature of MOOCs—the use of videos and quizzes—which allowed students to simply ‘watch the videos and do the assignments’ (Washington Post, 5.9.2013). The ‘broadcast’ nature of these pedagogies was expressed most starkly in this description from the Chronicle of HE (13.8.2012)—‘one person can teach the whole world with a cheap webcam and an internet connection’. Tellingly, the pedagogic limitations of these forms of teaching and learning were rarely commented upon. As one atypical headline from the Times Higher Ed (18.10.2012) questioned: ‘nice publicity, shame about the pedagogy’.

Third, were occasionally perceived tensions between MOOCs as a global or local phenomenon (n=43). In the former sense were declarations of MOOCs as ‘the university of the world’ (Australian, 5.11.2012), with a ‘truly international’ (Age, 23.10.2012) reach ‘around the world’ (Washington Post, 19.10.2012; Chronicle of HE, 1.10.2012; Age, 2.10.2012; Washington Post, 24.8.2013). In contrast, were more nationally-bounded descriptions of MOOCs. These stories featured talk of ‘British MOOCs’ (Times Higher Ed, 21.3.2013), a ‘Hong Kong MOOC’ (Chronicle of HE, 22.4.2013) and the US-centric notion of ‘teaching to the world from Central New Jersey’ (Chronicle of HE, 3.9.2012). Indeed, in this latter sense the Times Higher Ed (4.4.2012) reported ‘doubts about uncollaborative and ‘imperialist’ US platforms’.

Nearly as much concern was shown over matters of assessment (n=40), particularly with regards to matters of credentialing, grading, qualifications and measuring quality. One primary concern here was how MOOCs fitted with the traditional university forms of credentialization, with questions raised over ‘campus credit for online classes’ (New York Times, 12.3.2013). Two specific ‘issues’ along these lines recurred within the data. Firstly, were issues of grading and assessment, with questions raised over proposals for some MOOCs to use automated grading software, or ‘a digital auto-grader’ as the Chronicle of HE (3.9.2012) described it. These concerns were encapsulated in the faux-alarmist New York Times (12.4.2013) headline ‘That dastardly computer gave my essay a D!’. A second area of consternation was the prospect of universities awarding certificates for a fee—‘online classes will grant credentials, for a fee’ (Washington Post, 9.1.2013), and the associated risks of online test-takers being able to succeed fraudulently—‘cheating no credit to open course students’ (Age, 28.8.2012).

Teachers who were involved in the development and running of MOOCs—although featured only in 35 headlines and descriptions—were portrayed generally in exceptional terms. These were ‘dynamic, learned professors’ (Chronicle of HE, 3.6.2013); ‘star professors’ (Chronicle of HE, 18.6.2012); and ‘the world’s most esteemed professors’ (Australian, 5.11.2012). MOOCs therefore offered students the opportunity to experience a ‘daily dose of demigod’ (Times Higher Ed, 3.10.2013), or even a chance to engage with celebrity—‘some professors becoming the Kim Kardashians of the academic world’ (Australian, 5.11.2013). In contrast, and as one might expect, dissenting teachers were portrayed in less exceptional terms—that is, ‘scholars sound the alert from the ‘dark side’ of tech innovation’ (Chronicle of HE, 8.5.2013); ‘a chance to get rid of duff scholars’ (Times Higher Ed, 24.10.2013); ‘MOOCs’ revolution spooks academics’ (Times, 27.9.2013) and a ‘faculty backlash’ (Chronicle of HE, 6.5.2013). Notably, teachers not engaging fully with MOOCs tended not to be ‘professors’, but scholars, academics and faculty.

The actual technology of MOOCs was mentioned only occasionally (n=26), and then in vague terms. MOOCs were defined loosely as an ‘education technology platform’ (Australian 31.7.2013) or ‘higher education by computer, iPad or smartphone’ (Australian, 1.8.2012). The technology of MOOCs was most often defined in association with more familiar digital platforms. Thus MOOCs were defined as ‘the iTunes of academe’ (Australian, 31.7.2013) and ‘the YouTube of online learning’ (New York Times, 11.9.2013). As the Chronicle of HE (3.9.2012) surmised: ‘The term ‘MOOCs’ is meant to parallel the video-game acronym ‘MMOGs’ or massively multiplayer online games—collaborative worlds, like World of Warcraft, that have attracted millions of devoted players around the world’.

As with teachers and technology, there was also very little discussion of the business and economic aspects of MOOCs (n=20), with only a few headlines and definitions focusing on the potential role of MOOCs in selling higher education (‘MOOCs: new money for old rope’—Times Higher Ed, 14.2.2012; ‘MOOCs: vending machines of learning—Australian, 21.8.2013). Conversely, doubts concerning the profitability of MOOCs were rare—that is, ‘information wants to be free, but does education?’ (Washington Post, 2.11.2012); ‘more to MOOCs than moolah’ (Times Higher Ed, 10.1.2013). Even less concern was shown with the content of MOOC provision (n=18). The content of these courses was mentioned only with respect to subjects and topics of study that were seemingly incongruous in a technological setting (e.g. ‘making his MOOC an “outreach for poetry”’ Chronicle of HE, 29.4.2013; ‘from single-digit addition to the history of Chinese architecture to flight vehicle aerodynamics’ New York Times, 13.10.2013), or when MOOCs were being developed for serious provision—such as when the International Monetary Fund announced plans to establish their own MOOCs—‘IMF offers public lessons in finance’ (Times, 20.6.2013).

Similarly, the nature of the learning taking place through MOOCs was mentioned rarely (n=16)—depicted usually in terms of ‘opening minds’ (New York Times, 20.11.2012); ‘MOOCs break down barriers to knowledge’ (Australian, 12.12.2012) and even ‘Ivy League online education going to give the Flynn Effect extra juice’ (Washington Post, 10.5.2012). Finally, and perhaps most surprisingly, students were also notable by their absence from all but 15 of the headlines and descriptions. On the occasions that they did feature, this was in terms of students either being advantaged by studying in MOOCs over more traditional forms of learning (‘putting students centre stage’ Guardian, 9.7.2013; ‘gives students what they want’ Age, 5.6.2012), or conversely in need of ‘rights protection’ (Times Higher Ed, 31.1.2013). Otherwise, students did not appear as an integral element of what MOOCs were and what they meant.

These news media headlines and descriptions will certainly have informed many people’s understandings not only of what MOOCs are, but also their wider societal significance. From this basis, then, it would be reasonable to have drawn the following conclusions. That is, MOOCs are clearly a portentous development in the current higher education marketplace. They have emanated from elite US universities in a spirit of online expansion (and perhaps even outreach). In this sense MOOCs are reinforcing the established status quo in higher education—offering an alternative ‘way in’ to later study for ‘proper’ courses at ‘proper’, ‘face to face’ universities. MOOCs are courses that are taught by leading professors and, even in their most modest form, will involve thousands of students or more. The main concern that one need have with MOOCs is economic in nature, with large numbers of students engaging in university-level education for no fee or charge. In contrast, the pedagogical and technological characteristics of MOOCs are of little interest. Indeed, MOOCs are best seen as online versions of familiar university classroom pedagogies—that is, the lecture, the seminar and the tutorial. Similarly, the technological character of MOOCs is akin to familiar, established content-sharing and content-distribution applications (iTunes, YouTube, Google and so on). These familiar features reflect a sense of MOOCs either developing as part of a natural evolution of technology, or else a deliberate process of scientific innovation.

Of course, this analysis is restricted to the concerns of news media based in the US, UK and Australia. As such any conclusions need to be set against the particularities and boundaries of these respective national higher education landscapes – not least the well-established massification and marketization of university education. Indeed, the predominance of commodified ‘traditional’ forms of higher education in the US, UK and Australia undoubtedly have a bearing on these recent understandings of online education. As such, there is clearly room for additional comparative work that maps the discursive constriction of MOOCs in other national contexts – such as the largely publically-funded Scandinavian and central European education systems, as well as emerging higher education systems in regions such as Africa and the Middle East.

These limitations notwithstanding, there are a number of points to make about the persuasive but limited discursive constructions apparent within the news discourses examined in this paper. First, these descriptions and meanings differ considerably to the ways in which MOOCs have tended to be imagined and discussed within specialist educational technology circles. Second, these news media constructions are more straightforward, and certainly more conservative, than the increasingly contentious ways in which MOOCs are discussed on social media and in educational technology conferences, journals and other academic forums. Third, these discourses from the likes of the New York Times, Chronicle of HE, et al. reflect clearly the subsuming of MOOCs into the concerns and interests of the higher education establishment. Unlike their portrayal in many parts of the educational technology profession, MOOCs are certainly not understood as a countercultural, subversive or alternative element of higher education.

Indeed, unlike some of the prevalent discourses within online and professional domains, MOOCs do not appear to have been the subject of a pronounced deluge of hyperbole in the mainstream news media. Instead our data show a fairly consistent level of stories over the past 24 months or so—certainly not constituting a rapid over-saturation of the topic. Similarly, there has been little sign of a backlash against MOOCs in these mainstream sources. For example, while concerns over the relatively high levels of student dropout and disengagement from courses might have been mentioned elsewhere in articles, such negative issues did not rise to be key defining features or headline issues apart from a small handful of stories at the end of 2013 when mention began to be made of ‘setbacks’ (New York Times, 11.12.2013), ‘high hopes trimmed’ (New York Times, 17.12.2013) and ‘MOOC disengagement’ (Guardian, 13.12.2013). Only in December 2013 did an overtly critical headline appear, with the Washington Post (12.12.2013) enquiring plaintively, ‘Are MOOCS already over?’.

In terms of the research questions set out at the beginning of this article, are a number of issues that therefore merit further consideration. In particular there are important questions to ask about whose interests these news media discourses and meanings about MOOCs benefit—thereby questioning the extent to which these constructions of MOOCs are situated within dominant structures of production, power and privilege. Approached in this light, then, concerns should certainly be raised over the rather anodyne depictions of the dynamics underpinning MOOCs’ rise to public prominence. The notions of MOOCs either as a force of nature or a facet of scientific innovation both serve to obscure the socio-technical origins of these educational forms. The descriptions of MOOCs highlighted in this article are ahistorical in a number of significant and concerning ways. First, most of these stories make little or no connection between the recent rise of MOOCs and the wider struggles over higher education markets, funding and governance that have arisen in direct connection to the past thirty years of neoliberal reform of universities. In this sense, MOOCs are certainly not an unprecedented or new phenomenon—rather they are deeply implicated in the longstanding politics and economics of higher education. A second facet of this a-historicism is how these news discourses also give little credence to the past thirty years of e-learning research and practice—not least the efforts of open education and connectivist communities in originating the open courseware and ‘c-MOOC’ concepts during the 2000s. Indeed, only one of the 457 stories made explicit mention of the efforts of George Siemens, Stephen Downes, Dave Cormier and others (‘writers of the MOOC origin story are not fans of the original’ Times Higher Ed, 17.10.2013). Here too, there is a significant ‘alternative’ heritage of shaping influences behind the seemingly rapid rise of MOOCs that is obscured and silenced in the news media.

Also problematic is the partial visibility within news media discourses of many of the key actors and interest groups implicated in the actual growth of MOOCs. For example, these news accounts convey a narrow representation of university institutions as a small number of elite, Ivy League, ‘big fish’ institutions. Similarly, university teachers are portrayed predominantly as ‘world leading’ professors and ‘rock star’ high flyers. The only other high-profile actors in these stories tend to be the poster boys/girls of the major MOOC providers—the innovative inventors and ‘Stanford scientists’, such as Sebastian Thrun, Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller. Of course, the high level of visibility afforded to these elite individuals and institutions is accompanied by a corresponding obscuring of many other significant actors and interests. For example, as we have noted above, painfully little is said within these news accounts about students, beyond suggestions of homogenous masses of passive consumers. Little is said about the vast numbers of MOOC tutors who do not fit into the category of ‘rock star’—that is, the less exalted, far less securely employed foot soldiers of higher education who are actually responsible for the bulk of MOOC teaching. Little is also said about the non-elite, non world-leading universities that are developing and running MOOCs out of ‘Anytown’ USA (or Canada, China, Chile and so on). Perhaps most obviously, little is said about the role of the private sector enterprises, the venture capitalists and shareholders who have invested in and around the nascent MOOC industry in the hope of riding an e-learning financial wave to big returns.

These partial portrayals all serve to obscure some of the most significant dynamics of the recent rise to prominence of MOOCs—not least power imbalances and the domination of elite interests, continued hierarchies and unequal social relations between institutions, teachers and students, and the perpetuation of long-standing inequalities of opportunity and outcome. Take, for example, the notion conveyed in mainstream news stories that MOOCs are taught by privileged professors and taken by masses of students regardless of their circumstance. This belies the reality of a situation where many MOOCs are being taught by largely undistinguished and disempowered faculty and taken/completed mainly by a minority of educated privileged students (see Emanuel, 2013). Not only are these news media discourses obscuring the emerging evidence of MOOCs benefiting students who are already academically privileged rather than democratizing educational participation, but they also serve to side-line important issues relating to the casualization, deprofessionalization and outsourcing of academic labor. Similarly obscured are issues relating to the economics of MOOCs. Where is the reporting and discussion of the role of multinational corporations such as Pearson in supporting the administration of MOOCs, or multi-million dollar investments by venture capitalists? Taken on its own terms, these news media discourses reflect little of the major implications of MOOCs with regards to the potentially radical reform of relationships between the individual and the commons, the public and the private, non-profit and for-profit interests. The over-riding sense that one gains from reading these accounts is that of MOOCs as straightforward product rather than MOOCs as complex and messy process.

There is much more that our research project will address in subsequent analyses—not least how these descriptions, understandings and meanings are remediated from their ‘old media’ origins in arenas such as the New York Times into online comments pages and then onto the blogosphere, Twitter and other social media forums. Yet while the current commentary and debate about MOOCs undeniably is taking place on a diverse poly-medial basis, it would be unwise to dismiss the discursive construction of MOOCs in the established news media sources covered in this article as somehow peripheral to ‘real’ meaning-making in the digital age. On the contrary, these old media continue to be sites where the vast majority of the general public (and a good proportion of education professionals) are being exposed to the notion of ‘MOOCs’. These also are the media sources that continue to exert a disproportionate influence on policymakers and decision-makers, both in government and within higher education institutions. As such, these news media should be seen as having a large bearing on the continued progression of MOOCs from niche educational technology fad to mainstream educational form.

Seen in this light, then, there is clearly a need for more informed and nuanced descriptions and meanings to be added to these debates within news media around the world. While it might appear a minor matter, contesting the language, definitions and implicit assumptions currently being used to describe MOOCs within popular discourse could be seen as an important task for those in the educational technology and e-learning communities to take up. As the data in this article have demonstrated, language and discourse are integral elements of the politics of contemporary education—maintaining the parameters of what is, and what is not, seen as preferable and possible. Challenging—and offering alternatives to—something as apparently trivial as the ways in which MOOCs are being talked about in mainstream news media is therefore an important element of influencing the future conditions of digital higher education. Supporters and opponents of MOOCs in their various guises are well advised to take note, and to take action.

Brookes, H. (1995). Suit, tie and a touch of ju-ju: A critical discourse analysis of news on Africa in the British press. Discourse and Society, 6(4), 461-494.

Emanuel, E. (2013). Online education: MOOCs taken by educated few. Nature, 503, 342, 21st November.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. London: Routledge.

Gerhards, J. (1995). Framing dimensions and framing strategies. Social Science Information, 34(2), 225-248.

Johnson, T., & Avery, P. (1999). The power of the press. Theory and Research in Social Education, 27(4), 447-471.

Liyanagunawardena, T., Adams, A., & Williams, S. (2013). MOOCs: A systematic study of the published literature 2008-2012. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1455/2531

MacLachlan, G., & Reid, I. (1994). Framing and interpretation. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Rogers, R., Malancharuvil-Berkes, E., Mosley, M., Hui, D., & Joseph, G. (2005). Critical discourse analysis in education. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 365-416.

Taylor, S. (2004). Researching educational policy and change in ‘new times: Using critical discourse analysis. Journal of Education Policy, 19(4), 433-451.

© Bulfin, Pangrazio, Selwyn