|

|

|

|

|

|

Alexandria Walton Radford1, Jessica Robles1, Stacey Cataylo1, Laura Horn1, Jessica Thornton2, and Keith Whitfield2

1RTI International, USA, 2Duke University, USA

While press coverage of MOOCs (massive open online courses) has been considerable and major MOOC providers are beginning to realize that employers may be a market for their courses, research on employers’ receptivity to using MOOCs is scarce. To help fill this gap, the Finding and Developing Talent study surveyed 103 employers and interviewed a subset of 20 about their awareness of MOOCs and their receptivity to using MOOCs in recruiting, hiring, and professional development. Results showed that though awareness of MOOCs was relatively low (31% of the surveyed employers had heard of MOOCs), once they understood what they were, the employers perceived MOOCs positively in hiring decisions, viewing them mainly as indicating employees’ personal attributes like motivation and a desire to learn. A majority of employers (59%) were also receptive to using MOOCs for recruiting purposes—especially for staff with technical skills in high demand. Yet an even higher percentage (83%) were using, considering using, or could see their organization using MOOCs for professional development. Interviews with employers suggested that obtaining evidence about the quality of MOOCs, including the long-term learning and work performance gains that employees accrue from taking them, would increase employers’ use of MOOCs not just in professional development but also in recruiting and hiring.

Keywords: MOOCs; recruitment; hiring; professional development; human resources

Originally, much of the discussion surrounding MOOCs involved how they could be used to help students complete educational credentials. Yet recent research from the University of Pennsylvania suggests that over two-thirds of those taking MOOCs (massive open online courses) self-identify as employees. Moreover, while just 13% are taking MOOCs to gain knowledge to earn a degree, 44% are taking them to gain specific skills to do their job better and 17% are doing so to gain specific skills to get a job (Christensen et al., 2013). These findings suggest that a majority of individuals are taking MOOCs to prepare for or advance their careers. At the same time, major MOOC providers are beginning to realize that employers may be a potential revenue stream (Chafkin, 2013).

Yet employees’ ability to use MOOCs to facilitate their career success and MOOC providers’ ability to secure revenue from employers depends in large part on employers’ receptivity to MOOCs. While the press has provided anecdotal accounts of how a few employers have incorporated MOOCs, more systematic research based on a larger pool of employers, and not just the converted, has been missing from the discussion.

Determining the extent to which taking and completing MOOCs can help individuals (particularly those who are less advantaged) advance in their careers and help fill key employer needs is critical to understanding and capitalizing on the MOOC phenomenon. To explore the current and future roles that MOOCs can play with employers, Duke University, in partnership with RTI International, conducted a quantitative and qualitative study called Finding and Developing Talent: The Role of MOOCs (FDT).

The FDT project first conducted a short, multiple-choice web survey between November 15, 2013, and January 23, 2014. The survey was designed to answer four key research questions:

In addition to the survey, the project conducted qualitative interviews with a subset of 20 survey respondents. These interviews explored employer perceptions of the pros, cons, and feasibility of using MOOCs in recruitment, hiring, and professional development. The phone interviews were completed between December 12, 2013, and January 24, 2014, and participants were selected to ensure that individuals who had a range of experience with and knowledge of MOOCs (as indicated by their survey responses) were included in the interview sample. Interviews were coded using NVivo software. Differences in interview responses by the organization’s use of MOOCs, consideration of using MOOCs, and ability to envision using MOOCs were analyzed and are noted whenever they occurred in the Results section of this article.

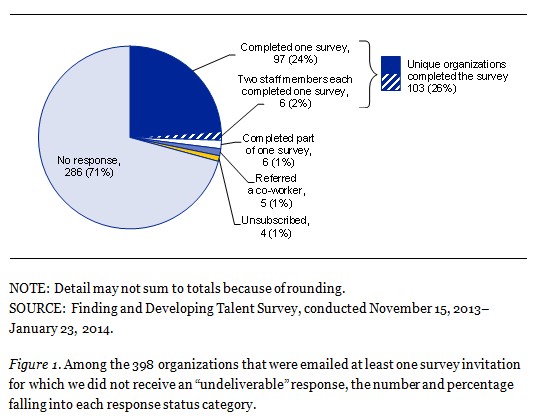

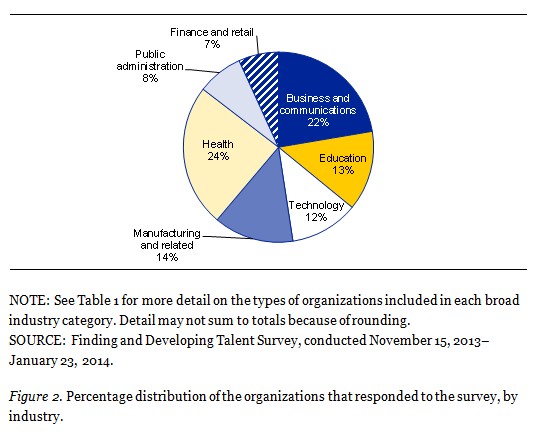

For a variety of reasons, the sample was drawn from employers in North Carolina—a state with the 10th largest population in the United States and a GDP the size of Sweden’s (North Carolina State Government, 2013). The FDT project obtained 706 email addresses for HR staff working for organizations with employees in North Carolina. Of the 706 email addresses sent invitations to participate, 207 undeliverable responses were received, suggesting the study may have had as many as 499 “working emails.” Because an email address was available for multiple HR staff members at some organizations, the 499 “working email” invitations were sent to a total of 398 organizations. Figure 1 shows the distribution of these 398 organizations by completion status. A total of 103 unique organizations (26%) answered all four questions in the web survey. As Figure 2 illustrates, the organizations in the study represent an array of industries. See Table 1 for more detail on the types of organizations included in each broad industry category.

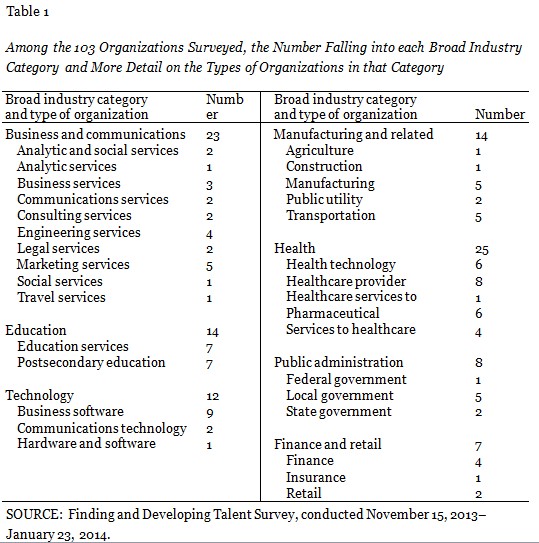

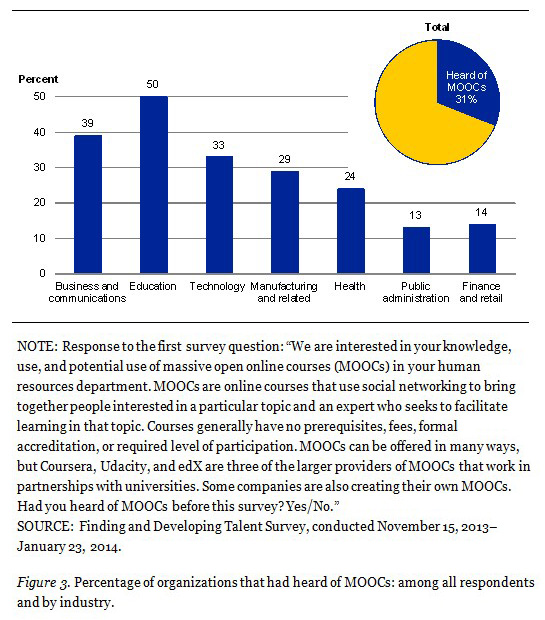

As quoted in Figure 3, the first survey question gave a brief description of MOOCs and asked respondents if they had heard of them before the survey. Some 31% of the HR staff at the organizations surveyed answered “Yes.” While this percentage may seem low, the finding is consistent with those from other surveys about the general public’s knowledge of MOOCs (Brodeur Partners, 2013). Moreover, the term MOOCs was coined as recently as 2008 (Liyanagunawardena, Adams, & Williams, 2013), and two of the leading MOOC providers (Coursera and edX) were founded as recently as 2011 and 2012, respectively (Rivard, 2013; Bombardieri & Landergan, 2013).

By broad industry category, half of all HR respondents from Education organizations had heard of MOOCs, as had 39% of those categorized as Business and communications organizations and 33% of those working in Technology. Awareness of MOOCs was lower (13 and 14%, respectively) among HR staff working in Public administration and Finance and retail.

Interviews revealed that those who were familiar with MOOCs at the time of the survey first learned about them in different ways. Sometimes the organization’s management saw press coverage of MOOCs or thought that MOOCs might offer potential cost savings and asked HR staff to investigate this issue. Other times, employees taking MOOCs on their own started the discussion within the organization. For example, as one interviewee said,

An employee brought [MOOCs] to our attention. [We] started discussion groups through [major MOOC provider]. . . . [MOOCs have been] a great opportunity to provide variety and content to staff. . . . [We] made our staff aware of those opportunities to tailor learning to different topics they are interested in.

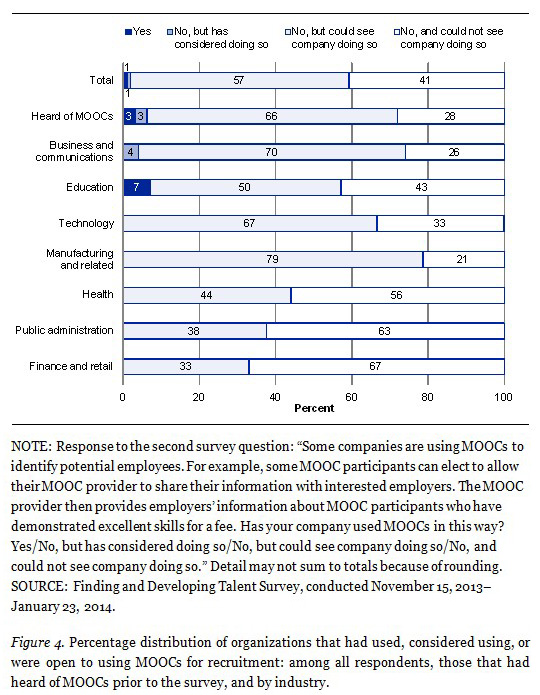

The second survey question asked HR staff whether their organization had worked with a MOOC provider to identify and recruit individuals who have demonstrated excellent skills in a MOOC(s). As Figure 4 shows, only one organization (in Education) reported using MOOCs for recruitment, and only one additional organization (in Business and communications) reported having considered using MOOCs for this purpose.

The low incidence of using MOOCs for recruiting purposes is not particularly surprising because some of the main MOOC providers only started pilot-recruiting programs as recently as 2012 (Young, 2012; Jones-Bey, 2012). Moreover, by December 2013 and January 2014, edX and Udacity announced that they had abandoned these programs, with edX suggesting that they found “Existing HR departments want to go for traditional degree programs and filter out nontraditional candidates” (Udacity, 2012; Kolowich, 2013). Consistent with edX’s claim, our interviews did suggest that taking a MOOC was most often perceived as an “extra” that reflected more about potential employees’ motivation and desire for continued learning than about demonstrating specific knowledge—particularly knowledge equivalent to that acquired in a traditional degree program.

Despite the low percentage of organizations using and considering using MOOCs for recruiting, once ways of using MOOCs for recruiting were described, more than half (57%) of all organizations surveyed could see themselves using MOOCs for recruitment. An even greater percentage of those that had heard of MOOCs prior to the survey (two-thirds) could envision this use. Interviews suggested that some of that receptivity may have had to do with the fact that most organizations interviewed were already using social media recruiting tools, with LinkedIn being most popular.

Nevertheless, a sizeable minority (41%) of all organizations could not see using MOOCs for recruitment. In interviews, HR staff from these organizations explained that they favored in-person methods over online ones. Others did not do any recruiting and instead relied on applications submitted through a website. Thus, organizations that seek employees who are more geographically dispersed, thereby making in-person recruiting less feasible, or organizations that have more flexibility in their recruitment practices may be more open to using MOOCs in this way.

Further industry analysis indicates that while organizations in two industry categories—Technology as well as Manufacturing and related—had not yet used or considered using MOOCs for recruiting, receptivity for doing so was high: 67 and 79%, respectively. In contrast, organizations in both Public administration and Finance and retail were more skeptical. Roughly two-thirds (63 and 67%, respectively) could not see their companies using MOOCs in this way. This view may reflect these organizations’ lack of familiarity with MOOCs because these were the two industry categories that were least likely to have heard of MOOCs before the survey. In fact, eight out of nine respondents in these industry categories who reported they could not see their organizations using MOOCs for recruiting also had not heard of MOOCs. Greater recruitment restrictions may also help explain the more tempered reception of those working in Public administration.

Interviewers also probed about the types of hires for which MOOCs might be particularly helpful in recruiting. Respondents viewed using MOOCs to recruit for jobs that required a broad range of skills or experience as challenging. “[We do] specialized recruiting. One course is not critical; [It’s] really experience level.” The need for multiple factors in considering whom to recruit was also noted. One such interviewee indicated that a MOOC course was not enough to identify a promising candidate. “We don’t hire many entry level [employees] that a [MOOC] completion certification would merit. . . . I can’t see [our company] today saying that ‘This person completed this certificate [so] let’s contact them for this job.’”

On the other hand, some interviewees thought MOOCs could be particularly useful in recruiting if they provided specific technical training in high-demand areas where potential employees were hard to find. As one interviewee explained,

[we have thought about using MOOCs for recruitment] because primarily we look for people with computer science degrees to succeed in roles here, but now with competition the way it is, it’s difficult to recruit experienced individuals. We are looking for creative ways to do things.

Another similarly indicated,

This is a tight market. We rely on software developers that fit our culture and I expect that our need will only increase as we continue to grow and change to a more software based company. . . . Any tactic that we could use to get our name to talented developers would be useful.

For the potential of MOOCs in recruiting to be fully realized, HR staff highlighted three needs. First, they wanted to be confident that the MOOC taught the specific skills needed. As one respondent related, “[Using MOOCs would be dependent on] the right test and curriculum to pull people. A lot of stuff we do is for researchers and techs, [so needs are pretty specific] in terms of skill sets.” Similarly, another indicated,

We have a really hard time recruiting engineers and software developers. . . . We are looking for [x programming language] expertise . . . that is pretty attractive. [I could see us using MOOCs for recruiting] if they have the specific courses we are looking for.

Second, staff who were interviewed wanted evidence of learning so they could trust that a potential hire who had completed a MOOC course had the skills he or she claimed to have. Third, and relatedly, using MOOCs for recruiting would be particularly appealing if MOOCs could make it easy to find and recruit the candidates with the skills needed rather than having to rely on traditional methods of reading through resumes.

Yet recruiting is just one part of filling an employer's workforce. Some employers do not use recruiting at all, while others fill only some positions through recruiting. Whether candidates have been actively recruited or not, employers still must decide among candidates. And oftentimes they have limited information on which to base their decision, for example, a cover letter, a resume, an interview, and a reference. It is therefore important to examine whether employers can use MOOCs to help them differentiate among applicants and to identify better potential employees. If they can do so, taking and completing MOOCs is likely to become even more appealing to those seeking new jobs.

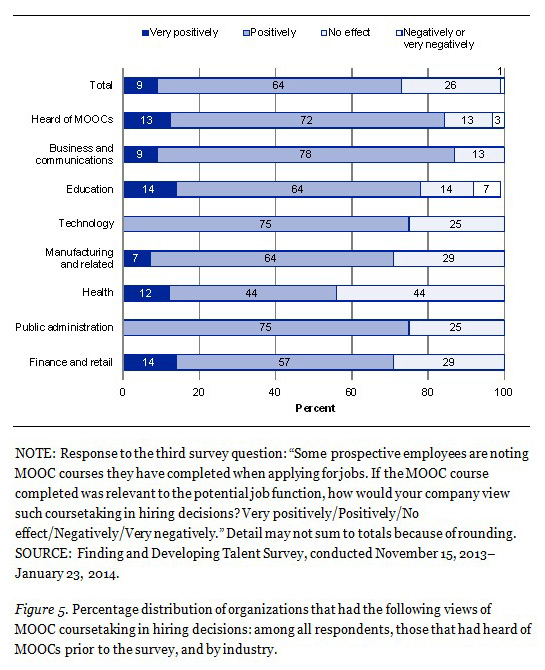

For these reasons, the third survey question asked HR staff to rate how potential employees taking MOOCs relevant to their potential job function would be perceived in hiring decisions. As Figure 5 shows, organizations were receptive to MOOCs when it came to hiring. Specifically, 9% viewed MOOCs very positively, and nearly two-thirds (64%) viewed them positively. Among those that had heard of MOOCs, those percentages were even higher. Some 13% reported very positive views, and 72% reported positive views.

No respondents viewed MOOC coursetaking in hiring very negatively, and only 1% viewed such coursetaking negatively. (Not surprisingly, this one HR respondent who had a negative view could not see his or her organization using MOOCs for recruitment either.)

Some key differences emerged in employers’ views about using MOOCs in recruiting and hiring when comparing responses across MOOC experience levels and industries. However, differences tended to vary within a range of neutral to very positive responses.

Both the one organization that reported using MOOCs in recruiting and the one organization that had considered doing so viewed taking a MOOC positively for hiring purposes. And of the 59 organizations that could see their organization using MOOCs for recruiting, 87% viewed MOOCs positively or very positively in hiring. Even among the 42 organizations that could not see their organization using MOOCs for recruiting, 53% still perceived them positively or very positively for hiring, and 45% viewed them as at least neutral.

Examining responses by industry revealed particularly positive views by organizations in Business and communications: They were most likely to view MOOCs as either very positive or positive (87%), followed by Education (78%), Technology and Public administration (each 75%), and Manufacturing and related and Finance and retail (each 71%). Health organizations were less receptive, with a majority (56%) reporting a very positive or positive reaction, and the remaining 44% reporting that such coursetaking would have no effect.

Interview responses suggest that positions in Health and other industries that require using specialized equipment may be less receptive because, as one HR staff member explained, his or her organization’s positions require extensive lab experience, which necessitates in-person training not deemed possible through MOOCs. Organizations that have less flexible hiring practices may also be prevented from considering MOOC coursetaking. A representative from one such organization reported that MOOC coursetaking would have no effect on hiring decisions until there was a mandate from management to consider MOOC coursetaking in hiring.

In thinking about the role that MOOC coursetaking may play in hiring, it is important to understand how such coursetaking is perceived compared with taking courses in other types of learning environments. HR staff stressed that traditional credentials were still the standard measure of skills rather than MOOC completion, and they were less likely to view MOOC coursetaking as demonstrating specific know-how. Yet because MOOCs are not seen as a prerequisite for hiring and usually do not provide college credit, HR staff tended to perceive MOOC coursetaking as a sign of positive character traits such as dedication and motivation. Specifically, potential hires who had taken MOOCs were seen as willing to continue learning on an ongoing basis and stay “up to date” in their field. They were also seen as having “drive and ambition” and as wanting “to do more for themselves, to develop themselves.” In sum, while MOOC coursetaking was not sufficient to influence a hiring decision by itself, it still tended to be perceived as a “plus factor” when evaluating personal attributes.

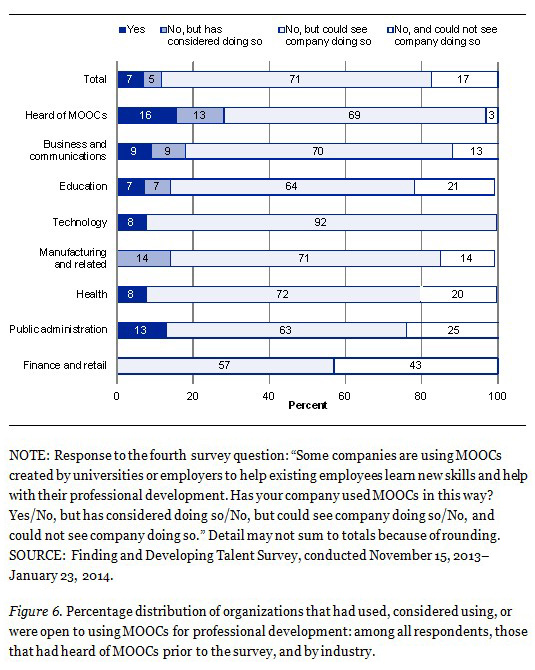

The final survey question asked respondents about their organization’s use or openness to using MOOCs to help existing employees learn new skills and advance in their professional development. Figure 6 shows that about 7% of organizations had already used MOOCs for professional development, reflecting somewhat early adoption of this practice considering that two of the largest MOOC providers were founded in 2011 and 2012, respectively (Rivard, 2013; Bombardieri & Landergan, 2013). An additional 5% indicated that their organization had considered using MOOCs, and another 71% could see their organization using them. Among respondents who had heard of MOOCs prior to the survey, receptivity for their use in professional development was nearly universal: Only 3% indicated that they could not see their organization using MOOCs for this purpose. These results highlight that there is great interest in, and a large potential market for, using MOOCs in this way.

Different industries responded with varying levels of enthusiasm. Of the seven organizations that had already used MOOCs for professional development, two were in Business and communications, two were in Health, and one each was in Education, Technology, or Public administration. All of the companies in Technology were at least open to using MOOCs for professional development. The Finance and retail sector was least receptive, with three such organizations (43%) reporting that they could not see their company using MOOCs for professional development.

Interviews suggested that organizations that were using, considering using, or could see their company using MOOCs for professional development tended to be using other online (as opposed to in-person) training more often than organizations that could not see using MOOCs for this purpose.

Interviewees noted multiple pros and cons for employees using MOOCs for professional development. A key benefit concerned giving employees the ability to engage in their own development, allowing them “to take what they want,” give them “goals to work on,” and help increase their “self-motivation.” MOOCs also enabled employees to take a “refresher course” or “stay up to date” in their field if they had been out of the traditional education system for a while.

Another benefit to using MOOCs for professional development had to do with enabling employees of all levels to advance in their careers. “Anyone could benefit from this if they had something they wanted to develop.” Another respondent agreed, “[Taking MOOCs] could be applicable to everyone. Low-level support staff [could take] classes on how to be more organized and have better time management . . . all the way up to higher level employees that [sic] want to learn about networking.”

At the same time, other respondents felt that MOOCs would be less appealing to employees with lower levels of education. While HR representatives did not think that employees who already had a college degree placed importance on whether they could receive college credit for MOOCs, respondents did think that employees without higher education credentials might prefer to spend any professional development time in courses that could help them earn credit toward a degree. Similarly, they believed those in jobs with continuing education requirements may be less inclined to take additional MOOCs—unless taking those MOOCs could count toward such requirements.

The online nature of MOOCs was seen as both an advantage and a disadvantage. The fact that taking a MOOC does not involve “a huge commitment to leave and go somewhere [like a college, a conference]” was viewed as a benefit, particularly for workers with families. Needing only an Internet connection to access the material was also viewed as especially beneficial for employees who traveled or worked remotely and therefore had a harder time accessing in-office professional development. Yet HR staff also noted that poor or limited Internet access could constrain access for some employees. Also, employees who are accustomed to a classroom setting or more interpersonal interactions might find it more difficult to persist in MOOCs.

MOOCs’ flexibility was also a pro and a con. On one hand, HR staff discussed how “It’s certainly easier for the user. They can access training materials and information at their convenience.” On the other hand, one HR representative explained, “When you have more flexibility then there is more difficulty in making deadlines and taking deadlines seriously. There could be less engagement than there could be in a more structured program.”

HR interviewees indicated that one possible solution for ensuring that the online nature and flexibility of MOOCs held employees’ interest, as well as resulted in greater accountability and completion, was to have employees take the same MOOC at the same time as a cohort. Some organizations were already doing so formally, others had employees who had taken the initiative to form groups, and others had heard that a cohort model had worked well at other organizations.

HR staff also noted multiple pros and cons for employers using MOOCs for professional development. The potential for using existing MOOCs to fill needs was one theme that they discussed. HR representatives appreciated the fact that MOOCs allowed them to expand the breadth of offerings their organization could provide. As one HR representative said, “I don’t think you can have too many options to take and choose from. If anything, [it’s] always helpful to have something available at work.” Organizations with a range of highly technical skilled employees found it especially hard to accommodate any one particular skill in a cost-effective manner. Thus, they felt MOOCs could help fill those gaps for specific demands. Still, HR staff also noted that MOOCs could not fill all training needs and stated, “[Some courses] aren’t going to be very well done in an online education [setting].” Certain training had to be “hands-on” and “more interactive to allow for clarification and [ensure employees] understood the material.”

HR professionals also considered the low cost of taking MOOCs as an advantage when thinking about using them for professional development, but this advantage was counterbalanced by the potentially high labor cost incurred for employees taking MOOCs during their work day. The fact that MOOCs are free was appealing because, in the words of one respondent, professional development is something that can be set aside when “the budget gets tight.” Similarly, another respondent highlighted the fact that because MOOCs are free, they would be a way to help their organization continue to provide professional development during a “budget crunch.” Yet while signing up for a MOOC is technically free, employers were starting to grapple with whether employees would take MOOCs during their work day or on their own time. The labor costs of more highly compensated employees taking semester-long MOOCs during their work day are not inconsequential. If such labor costs were to be incurred, organizations would want more evidence that the course was well taught and had a lasting impact.

HR staff felt that obtaining such evidence was currently difficult. Though several noted that MOOCs are largely taught by faculty at top universities and suggested that the content should therefore be of high value, the newness and online nature of MOOCs still made some wonder about their actual quality.

Finally, HR departments also reported that MOOCs offered by top universities as part of professional development could have positive spillover effects for recruitment and employee retention. A few organizations noted that they wanted to be seen as an “employer of choice” to talented recruits and potential new hires more broadly. They believed that highlighting the availability of professional development using MOOCs taught by prominent university faculty could help them recruit excellent candidates, and particularly job-mobile Millennials—who they claimed tend to be especially interested in training that will help them advance wherever their career takes them. And another HR staff member’s comments suggested that MOOCs might contribute to the retention of current employees, because MOOCs could enable organizations to provide professional development opportunities to employees at all levels, which would help all employees “know they are valued.”

Interviewers also asked respondents about the type of MOOC content that would be most valuable. Three broad areas were discussed: basic computer skills, soft skills in developing management and leadership, and highly specialized training such as software development.

The need for professional development in basic skills like Excel and Powerpoint was least commonly noted. And one HR interviewee felt the market for this type of training was already crowded with companies providing good systems to track progress in these subjects. Access to these types of trainings, however, tends to cost money, and thus free alternatives may be attractive to smaller companies with fewer professional development dollars.

There was greater interest in MOOCs focused on soft skills like “leadership,” “management,” “dealing with customers,” and “account management.” One representative who initially could not envision his organization using MOOCs for professional development said after he learned more: “I really didn’t understand [how MOOCs could work for professional development]. Now I feel like if I can find courses about leadership or management then I’d love to have the guys in office take part in that.” Another stated: “Management . . . is an area we are trying to grow and improve . . . [and that] employees want to develop.” Other HR departments were weighing whether it made sense to develop such courses in-house. As one HR staff member said,

Teaching soft skills . . . there is only a certain amount of content we could teach, but if we had something more convenient for people . . . from another company or course that could teach it, that would be beneficial.

In sum, while the sizeable number of employees interested in leadership and management could make it cost effective for larger organizations to develop such trainings internally, if quality MOOCs could provide the same or better information, that would be of interest to a range of organizations—particularly those with smaller professional development budgets.

Using MOOCs for highly specialized technical training was also of strong interest. As one HR representative explained, “We have a small internal training and HR staff. We’re only going to be able to deliver so much content. We know we’re not going to be the subject matter experts.” And unlike more soft-skill management and leadership classes, HR staff noted that outside professional development companies tended not to focus on specialized topics with limited pools of interested parties. As a result, employees were largely forced to rely on more expensive conferences and brick-and-mortar institutions for such training. MOOCs, with their broad geographic reach, were seen as potentially able to fill this gap. Specialized technical needs noted by respondents included a range of skills: analytics, technology, construction management, engineering design, blueprint design, and mental health/identification of mental illness.

MOOCs vary in course length, but the current preference is toward courses that run for about 6 weeks (Anders, 2013). When HR staff were asked about the course length that would be ideal if MOOCs were to be used for professional development purposes, a variety of time frames were given: “no longer than 10 weeks,” “7 to 8 weeks,” “no more than 6 weeks,” “4 to 6 weeks,” “1 month,” and “2 weeks.” Those who reported they could not see their company using MOOCs for professional development tended to indicate that professional development courses needed to be even shorter: “1 week,” “5 days,” and “half a week.” Other HR representatives noted that course length should be driven by course content. The desired workload for courses was also mentioned. One respondent felt courses should not require more than 5 to 10 hours of work per week or they would feel like a part-time job on top of the job employees already have.

Lastly, interviewees were asked what they needed in order to make MOOCs more useful in professional development.

To begin with, for employers to encourage their employees to use MOOCs for professional development, and especially if employers are going to provide employees with work time to take these courses, numerous interviewees discussed the need for evidence of MOOCs’ legitimacy, rigor, and quality. HR staff also wanted to know how MOOCs compared traditional courses on these measures. MOOCs’ well-publicized low completion rates (Parr, 2013; Reich & Ho, 2014) gave HR staff pause as to the quality and level of student engagement in MOOCs.

In thinking about how MOOCs might be determined to be of value in a professional development setting, it is helpful to understand how traditional courses are assessed. One HR professional explained how researchers and scientists at his company learned from others in their field which specific courses taught at traditional universities or conferences were worth attending, while “for MOOCs the awareness is not as clear. Which ones are good and which ones aren’t? Which ones don’t have people dropping left and right?” Although the cost of a MOOC makes taking it low risk, providing highly compensated staff with the time to take a MOOC that has not yet been vetted by others in the field comes with opportunity costs.

A second need expressed was evidence of completion. Organizations wanted evidence that employees were making progress toward and completing MOOCs they were taking as part of their official professional development. Some in the professional development field are already doing this. As one respondent related, “When we work with [private company x], [course completion] automatically downloads to [the employee’s] transcript and it downloads to the main system and we can track and assess.” MOOC providers are heeding this call. For a small fee, providers like Coursera and edX already enable courestakers to show verified proof that they completed a course (Coursera, 2013; edX, n.d.). Coursera is also exploring the possibility of selling dashboards or analytics tools to companies looking to track employee progress in online training courses (Nadeem, 2013a). And Coursera, edX, Udacity, and others have teamed with LinkedIn in a pilot program that publicly certifies MOOC completions (Nadeem, 2013b).

But tracking coursetakers beyond completion was also important. As one interviewee stated, “I think as we continue to present this to [management], they will want to know . . . how we can assess whether or not these individuals are actually learning.” And others wanted to be able to go beyond assessing the degree to which learning was retained and wanted to know if such coursetaking led to improvement in job performance. An HR staff member explained that to facilitate evaluation of behavior change, he would want information on the course’s learning objectives as well as a simple, short questionnaire or observation checklist that could be given to co-workers and supervisors. His organization was already using such tools for other professional development courses. Such measures and metrics would greatly add to employers’ ability to ascertain the value of a MOOC and encourage their adoption not just for professional development but also for recruiting and hiring.

The findings from this study suggest that the potential for employers’ use of MOOCs is strong. Though MOOCs are only a couple of years old and a majority of employers are just now hearing about them, some employers are already using them or have considered using them and many more could see their organization using MOOCs. Overall, almost three-quarters (73%) viewed MOOC coursetaking positively or very positively when making hiring decisions. A solid majority (59%) of employers were using, considering using, or could see their organization using MOOCs in recruiting, and more than four-fifths (83%) reported positive views for using MOOCs as professional development tools. Yet interviews also indicated employers’ need for evidence of MOOCs’ quality and easy ways to verify employees’ completion of these courses. From a professional development perspective, employers wanted to see assessments of long-term learning and behavioral gains.

Knowledge and use of MOOCs is rapidly evolving. In anticipation of expected changes in how employers perceive, use, and value MOOCs, the authors seek to build upon this study’s findings by conducting a national study that further investigates these issues. Findings from a nationwide study can illuminate ways that employers and MOOC providers might better capitalize on the potential of MOOCs to identify prospective employees and better train and provide professional development to existing ones.

The authors would like to acknowledge that the MOOC Research Initiative, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and housed at Athabasca University, provided financial support for the Finding and Developing Talent study. The authors would also like to express their appreciation for the help of Duke University’s Career Services in providing contact information for human resources staff at North Carolina employers. Bobbi Kridl, Andrea Livingston, Victor Perez-Zubeldia, Martha Hoeper, and Thien Lam of RTI International all provided excellent editing and production expertise. Last but not least, we would like to thank the study’s respondents. This research would not have been possible without their generous participation.

Anders, G. (2013, October 10). Coursera’s online insight: Short classes are education’s future. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/georgeanders/2013/10/10/courseras-online-insight-short-classes-are-educations-future/.

Bombardieri, M., & Landergan, K. (2013, May 21). 15 schools join online classroom initiative; Berklee, BU among new edX participants. The Boston Globe. Retrieved from http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2013/05/21/edx-pioneer-online-courses-founded-harvard-and-mit-doubles-size/VmMGcNYD37lLuVWkyKDwCK/story.html.

Brodeur Partners. (2013, June 26). Study suggests careful navigation in move toward massive open online courses [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.brodeur.com/posts/press-release/the-mooc-minefield-study-suggests-careful-navigation-in-move-toward-massive-open-online-courses/.

Chafkin, M. (2013, November 14). Udacity’s Sebastian Thrun, godfather of free online education, changes course. Fast Company. Retrieved from http://www.fastcompany.com/3021473/udacity-sebastian-thrun-uphill-climb.

Christensen, G., Steinmetz, A., Alcorn, B., Bennett, A., Woods, D., & Emanuel, E. J. (2013). The MOOC phenomenon: Who takes massive open online courses and why? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2350964.

Coursera. (2013, January 9). Introducing signature track [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://blog.coursera.org/post/40080531667/signaturetrack.

edX. (n.d.). Verified certificates of achievement. Retrieved March 21, 2014, from https://www.edx.org/verified-certificate.

Hill, P. (2013, June 4). MOOCs beyond professional development: Coursera’s big announcement in context [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://mfeldstein.com/moocs-beyond-professional-development-courseras-big-announcement-in-context/.

Jones-Bey, L. (2012, December 4). Coursera and your career [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://blog.coursera.org/post/37200369286/coursera-and-your-career.

Kolowich, S. (2013, December 16). edX drops plans to connect MOOC students with employers [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/edx-drops-plans-to-connect-mooc-students-with-employers/48987.

Kolowich, S. (2014, January 17). Credit-for-MOOCs effort hits a snag [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/credit-for-moocs-effort-hits-a-snag/49573.

Liyanagunawardena, T. R., Adams, A. A., & Williams, S. A. (2013). MOOCs: A systematic study of the published literature 2008–2012. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14(3), 202–227. Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1455.

Nadeem, M. (2013a, November 25). Coursera plans to develop corporate training program. Education News. Retrieved from http://www.educationnews.org/online-schools/coursera-plans-to-develop-corporate-training-program/#sthash.MpII1c6Q.dpuf.

Nadeem, M. (2013b, November 19). Linkedin to allow users to add MOOC certifications to profiles. Education News. Retrieved from http://www.educationnews.org/online-schools/linkedin-to-allow-users-to-add-mooc-certifications-to-profiles/#sthash.MZ9vZEM4.dpuf.

North Carolina State Government. (n.d.). About North Carolina. Retrieved March 17, 2014, from http://www.ncgov.com/aboutnc.aspx.

Parr, C. (2013). Not staying the course. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/05/10/new-study-low-mooc-completion-rates.

Reich, J., & Ho, A. (2014, January 23). The tricky task of figuring out what makes a MOOC successful. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/01/the-tricky-task-of-figuring-out-what-makes-a-mooc-successful/283274/.

Rivard, R. (2013). Free to profit. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/04/08/coursera-begins-make-money#ixzz2cW0yPYc6.

Udacity. (2012, June 28). Udacity’s career team is here to help you [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://blog.udacity.com/2012/06/udacity-career-placement-program-is.html.

Young, J. R. (2012). Providers of free MOOC’s now charge employers for access to student data. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from "http://chronicle.com/article/Providers-of-Free-MOOCs-Now/136117/.

© Radford, Robles, Cataylo, Horn, Thornton, Whitfield