|

Charity Akuadi Okonkwo

National Open University of Nigeria

Nigeria has joined the global race of teaching and learning in a changing educational environment by adopting open and distance learning (ODL). Although it is a global trend, ODL poses some challenges at local levels, one of which is the untimely production of teaching materials currently affecting instructional delivery in Nigeria. The modern approach to ameliorating this challenge is the deployment of open educational resources (OER), and this practice is enabled by information and communication technology (ICT). Hence, today’s educators need OER tools and ICT skills to address the changing nature of education. This paper assessed the needs, readiness, and willingness of ODL professionals from two dual-mode universities in Nigeria to deploy OER in teaching and learning. Data were collected using structured questionnaire items. The major findings of the study’s survey indicated that educators have not really embedded OER in teaching and learning, but they are very eager to be trained in the rudiments of OER and wish to employ them thereafter. The results indicate there is an urgent need for professional development to include training in the rudiments of OER for educators.

Keywords: Open education resources; educators; instructional materials; distance learner

“Everyone has the right to education” (United Nations, 1948, Article 26); this right was enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights over sixty years ago. Therefore, many countries are making a concerted effort to ensure that all people have the opportunity to be educated, a target in line with Education for All (EFA) and the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), which both placed emphasis on the issue. This effort is examplified in the modern adoption and deployment of open and distance education delivery systems in Nigeria to fulfill the nation’s commitment to provide education for all, within the context of reaching the World Forum on Education for All (EFA) goals by 2015. These goals involve ensuring that the learning needs of all young people and adults are met through equitable access to appropriate learning and life skillls programs; improving all aspects of quality of education; and ensuring excellence for all so that recognized and measurable learning outcomes are achieved, especially in literacy, numeracy, and essential life skills (Federal Ministry of Education, 2002).

The substantial efforts several governments have made to achieve EFA and MDGs have led to a significant increase in the number of children attending primary and secondary schools in developing countries (Wright & Reju, 2012). Many African countries have invested heavily in education because it is widely accepted as a leading instrument for promoting economic growth (Bloom, Canning, & Chan, 2006, p. 1), and Nigeria is not an exception. Nevertheless, higher education in Nigeria has been under immense pressure to grow from a population that increasingly demands access. The National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN), the premier open and distance learning (ODL) university in the country, was established to widen access to all. But demand is still high, so ODL has come to be recognized in Nigeria as a viable alternative to the conventional school system which hitherto dominated the country’s education sector. There are currently six schools in the country which may be regarded as dual-mode universities, with limited capacity to deliver degree programs using open and distance learning in addition to the conventional face-to-face mode (NUC, n.d.).

Researchers have observed that only 36% of those who want to enroll in secondary education programs in sub-Saharan Africa can find seats in schools (UNESCO, 2011). In Nigeria, this situation is even worse at the tertiary level of education, which is expected to provide the opportunity for those willing and able to further their studies. But providing education for all is a daunting task, considering the size of the country’s population (about 150 million), and the compelling needs of the people (Okonkwo, 2012). The ever-growing demand for education in Nigeria cannot be met by the traditional means of face-to-face classroom instructional delivery alone.

The National Open University of Nigeria was established because the capacity of face-to-face conventional tertiary institutions in Nigeria was insufficient. For instance, about 1.5 million candidates sat for the 2012 Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) in Nigeria. A breakdown of the applications to the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board (JAMB) showed that 83,865 individuals applied for admission at the University of Lagos in 2012, and 99,115 in 2011 (Alechenu, 2012); the school’s capacity, according to the National Universities Commission (NUC, the regulatory body for universities in Nigeria), is only 9,507. These figures only include applicants selecting the university as their most preferred choice, and do not include those who listed it as their second choice.

Also, in South Africa, 85,000 potential learners applied for one of the only 11,000 seats available at the University of Johannesburg (Polgreen, 2012). Allen (2010) opined that, “globally, of those 20 years old or younger people, 30 million are qualified to attend university, but there are no places for them. This number is likely to increase by 100 million in 2020.” In their own report, Atkins, Brown, and Hammond (2007) remarked that, “in order to serve the number of youths qualified to enter university in 2020, a major university would need to be opened every week.” This statement agrees with Wright and Reju’s submission (2012) that demand for education, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, is much greater than what existing and planned academic institutions can accommodate. UNESCO estimates (based on 2004 data) that 3.8 million teachers will have to be recruited by 2015 in Africa alone if the goal of universal primary education is to be achieved (United Nations, 2009, p. 16). According to Wright and Reju (2012), African governments do not have the financial resources to hire that number of teachers. For instance, between 1991 and 2006, the number of students registered in African higher education institutions rose by 16%, but expenditures on education rose by only 6% (World Bank, 2010). Hence, the demand for educational services is outstripping what countries are allocating to education.

In some local areas in Anambra State of Nigeria, teachers are hired and paid by the parent-teacher association (PTA) to teach in primary schools in order to make up for the shortage of the required number of teachers in the system. This challenge is not peculiar to Nigeria alone. The Niger Republic also hired “Volunteer” teachers (Lambert, 2004) who had no teaching experience and often lacked knowledge of subject matter they were teaching. In the Republic of Congo, some teachers were not paid for several years (Prozonic, 2011). These realities mean it is therefore not feasible for governments to continue to build, staff, and resource schools, universities, and teacher training facilities in order to meet the demand over the next 5, 10, and 20 years (Wright & Reju, 2012).

In order to fully realize the concepts of education for all and equitable access to educational oppportunities, experts are exploring other options. Notable opportunities are the increased use of distance education combined with information and communication technologies (ICTs), which have greatly influenced education and teaching practices in recent years, in addition to OER, which are being researched for use in both conventional and distance education settings.

It is clear that unless the assumptions that guide academics in open and distance learning are precisely defined, problems of “quality” and “equity” will haunt this mode of education (Das, 2010). There has been a remarkable increase in OER production since 2002, when it was first defined in a UNESCO workshop. There has also been a strong international debate on how to apply OER in actual practice, and UNESCO chaired a vivid discussion about this through its International Institute of Educational Planning (IIEP) (Das, 2010).

Before now, distance education referred to a kind of learning made possible over spatial distance between the teacher and the learner. But today’s open and distance education is no longer what it used to be. In the changing arena of higher education today, the description of open and distance education has to include “arrangements to enable people to learn at the time, place and space which satisfies their circumstances and requirements” (Das, 2010).Open education resources make learning available at the time of the learner’s choice and at a place suited to his or her requirements. Thus, addressing the issue of openness in distance education contextually and pedagogically brings along with it the need to use digital technologies and ICT beyond borders. I envisage OER as a tool to enable viable outreach in higher education systems in general, and ODL in particular, incorporating innovative strategies in teaching and learning. I also anticipate that OER are capable of enriching learning much more than the materials that we have in the face-to-face institutions, which hitherto have been handicapped by a lack of resources. Despite the laudable vision of ODL globally, it poses some challenges to educators in Nigeria (Okonkwo & Ikpe, 2011). For instance, the writing and development of instructional materials, the backbone of instructional delivery, continues to be a major hindrance to NOUN’s vision and mission (Okonkwo, 2012).

This paper focused on the premise of using open educational resources as viable tools for all professionals in open and distance learning to enable their successful participation in the changing educational environment. These resources are becoming increasingly accepted as part of the range of materials that learners and educators can use to bring about change in educational systems in a profound way. But the method of learning in this open way does not come naturally to everyone. Hence there is a need for educators to access continuing professional development in the effective use of open educational resources. Such training will equip them with the knowledge of how this open approach operates for teaching and learning. This paper therefore assessed the need for continuing professional development for educators with respect to open educational resources.

Open education resources are teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or creative common area and are freely available to anyone over the Web. They are an important element of the learning infrastructure and range from podcasts and digital libraries to royalty-free textbooks and games. There have been many definitions of OER; I provide four here.

Open Educational Resources (OER) are teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under the intellectual property right license that permits their free use or re-purposing by others. Open educational resources include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and any other tools, materials, or techniques used to support access to knowledge (Atkins, Brown, & Hammond, 2007).

Open Educational Resources (OER) are materials that may be freely used to support education and may be freely accessed, reused, modified and shared by anyone (Downes, 2011).

Open Educational Resources (OER) are teaching, learning and research materials in any medium that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others (Creative Commons, 2012).

Open Educational Resources are digitized materials offered freely and openly for educators, students, and self-learners to use and reuse for teaching, learning and research. OER includes learning content, software tools to develop, use, and distribute content, and implementation resources such as open licenses (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2007).

The above definitions illustrate that the definition of OER is maturing parallel to the increased adoption of open education by formal education institutions around the world.

Other scholars have also defined OER as teaching, learning, and research resources with intellectual property licenses that permit them to be reused, reworked, remixed, and redistributed (D’Antoni, 2009; Hilton, Wiley, Stein, & Johnson, 2009; Plotkin, 2010; Wiley, 2009). They observed that some conditions may be placed on the use of OER, such as the provision of attribution, but all OER are accessible to anyone. They are seen as having the potential to change the practice of learners, educators, and organizations in a profound way (McAndrew, 2010). These untapped resources have the potential to reduce costs, improve quality, and increase access to educational opportunities (Daniel, 2011; Plotkin, 2010; Wright & Reju, 2012). Educators can find free-to-use teaching content from around the world to add to the OER commons. The resources offer opportunities to create systemic change in teaching and learning through accessible content, and, importantly, they embed participatory processes in the courses that use them. The content comes from trusted individuals and organizations.

For ODL practitioners in Nigeria to benefit from this laudable trend of OER offerings in education, they have to be knowledgeable enough about the issues involved to use them. It is only when Nigerian educators have been trained that they can effectively contribute to the global discussion on OER and use them meaningfully in the education system.

Reliable sources of OER include (but are not limited to)

Some of these resources include understanding OER, finding OER, and OER in action.

The potential benefits of OER for users already identified in literature (Das, 2010) are

Open and distance learning institutions and educational leaders must grasp the potential of OER by making the collective commitment to use this innovation in order to pursue the goal of education for all. This can be achieved by building on the OER success stories of the African Virtual University (AVU), OER Africa, SAIDE, the Virtual University for Small States of Commonwealth (VUSSC, http://www.vussc.info/), and other African and global OER initiatives. In addition to earlier identified benefits, Wright and Reju (2012, p. 189) opined that OER

Kanwar, Kodhandaraman, and Umar (2010) noted that one of the emerging issues in educational discourse today is the development and use of open educational resources, and their potential to expand access to and improve the quality of education, particularly in developing countries where there is a dearth of quality materials. The Commonwealth of Learning (COL) supported the development of the Science, Technology, and Mathematics Program (STAMP 2000+) teachers’ training materials in the late nineties, long before the term OER had entered the educational lexicon (Kanwar et al., 2010). They stated that 140 course writers from eight south African countries, namely, Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, wrote 46 modules of material for training upper primary and junior secondary teachers. The modules focused on four subject areas: science, technology, mathematics, and general education. Yet an external evaluation of the COL’s programs conducted in 2006 revealed that there was very little attempt to use the modules by teacher education institutions in Africa (Spaven, cited in Kanwar et al.). The reasons ascribed for not using these materials as expected were lack of awareness about the program and its benefits; no clear strategy for implementation; and assumption that once OER are developed, teacher training institutions would automatically use them (Kanwar et al., 2010). They advocated based on the lessons learned from the above experience that, henceforth, there were three important issues to address.

The advocacy of Kanwar et al. (2010) can only be effective if teachers are first empowered with the necessary ICT skills. Giving basic ICT training will open more opportunities for them in the following ways:

The institution will also benefit if teachers start producing educational materials using multimedia because they will be able to develop their own customized content; instructors will be free to modify and update content from time to time according to curriculum requirements with minimum cost; and the teaching quality of the institution will increase. Teachers with ICT skills can also put their content on the Internet and get it peer reviewed. This will ensure that more resources on the Internet are authentic and valid. It will also allow individuals who are not able to get a formal education to access learning resources.

The concept of open educational resources has become well known in Nigeria. Nevertheless, the extent of educators’ use of OER and how they were used was not very impressive. This study assessed if there was a the need for continuing professional development of educators in the use of OER for teaching and learning. It identified the extent to which educators perceived and used OER in teaching and learning, their preferences for and regularity of use of OER tools, level of agreement with relevant OER issues, and their readiness to attend workshops or training on OER.

Data were collected using structured questionnaire items given to a focused group of academic staff from two Nigerian universities at a workshop on course material development for distance learners. The results of the study revealed the need for professional development of educators in the use of OER. The role of continuing professional development for educators in this regard remains clear. There is much to learn from OER in our globalized and digital world in terms of educational provisions; ODL professionals cannot afford to be left out. Hence, the need for continuing professional development for educators to ensure they can effectively use OER in ODL institutions cannot be overemphasized.

The objectives of this study are

The study used a survey which collected data with a structured questionnaire adapted from an unpublished RETRIDAL (2011) questionnaire on OER used for the National Open University of Nigeria community. The population from which the sample was drawn consisted of academic staff from Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH) in Ogbomosho and the Federal University of Technology (FUTA) in Minna. The sample consisted of twenty academic staff from the two universities directly involved with the development of course materials for distance learners. Out of the 20 participants, 19 responded to the questionnaire items. The 19 respondents consisted of 16 males and 3 females, with ages ranging between 31 and 56 years. They had varied amounts of teaching experience, ranging from 2 to 25 years in tertiary teaching as graduate lecturers in conventional institutions.

The data collected in the questionnaire were analyzed using SPSS 16. The analyses are descriptive, consisting of either a determination of the percentage of responses to items in various sections of the questionnaire, or both a determination of the percentage of responses using various Likert scales and calculations of the mean, standard deviation, and the variance for given items. The cutoff point for the acceptance of responses to research questions with percentages only was set at 55%. The 55% cutoff point served as benchmark for acceptance of a participant’s response to a given item because it is above average and therefore is meaningful. Thus, any response of 55% and above was accepted as favorable. This condition applied to objective 1 and 5. The Likert-type scale was used for objectives 2 to 4. The responses for objective 2 and their weight were very regularly (3), regularly (2), occasionally (1), and not at all (0). The boundaries of each response in the 3-point Likert scale from 0 to 3 was calculated by dividing the serial width (3) by the number of responses (4), and was found to be 0.75. This value was used to interpret the mean values. Thus, depending on this calculation, the accepted boundaries for each response to objective 2 are presented below:

0 = 0 + 0.75 = 0.75

1 = 0.75 + 0.75 = 1.5

2 = 1.5 + 0.75 = 2.25

3 = 2.25 + 0.75 = 3.0

A score of 2.25 and above on the scale was taken as a meaningful indicator of participants’ purposes for and the extent of their use of OER. Any score below 2.25 was taken as an indicator of participants’ low purposes for and limited extent of use of OER. These values were enough to meet the objectives. However, the variance (V) and standard deviation (SD) were also presented to show how the individual raw scores from which the mean was computed were dispersed (Okonkwo & Ikpe, 2011).

Also, the responses objective 3 and their weights were regularly (2), occasionally (1), and not at all (0). In this case, the boundaries of each response in the resulting 2-point Likert scale (from 0 to 2) was calculated by dividing the serial width (2) by the number of responses (3) and was found to be approximately 0.67. This value was used to interpret the mean values. Thus, depending on this calculation, the accepted boundaries for each response are presented below:

0 = 0 + 0.67 = 0.67

1 = 0.67 + 0.67 = 1.34

2 = 1.34 + 0.67 = 2.01 = 2.00

A score of 1.34 and above on the scale was taken as a meaningful indicator of participants’ preference for and regular use of OER tools.

Similarly, for objective 4 responses and weights were strongly agree (4), agree (3), disagree (2), strongly disagree (1), and not applicable (0). The boundaries of each response in the 4-point Likert scale were calculated by dividing the serial width (4) by the number of responses (5) and was found to be 0.8 (Topkaya, 2010). This value was used to interpret the mean values. Thus, depending on this calculation, the accepted boundaries for each response are presented below.

0 = 0 + 0.8 = 0.8

1 = 0.8 + 0.8 = 1.6

2 = 1.6 + 0.8 = 2.4

3 = 2.4 + 0.8 = 3.2

4 = 3.2 + 0.8 = 4.0

A score of 2.4 and above on the scale was taken as an indicator of participants’ moderate agreement with identified OER issues, while 3.2 and above showed strong agreement. Any score below 3.4 was taken as an indicator of low agreement with OER issues.

The data analyses and results are presented in the tables below. The tables show a summary of the research objectives dealing with the various sections of the study.

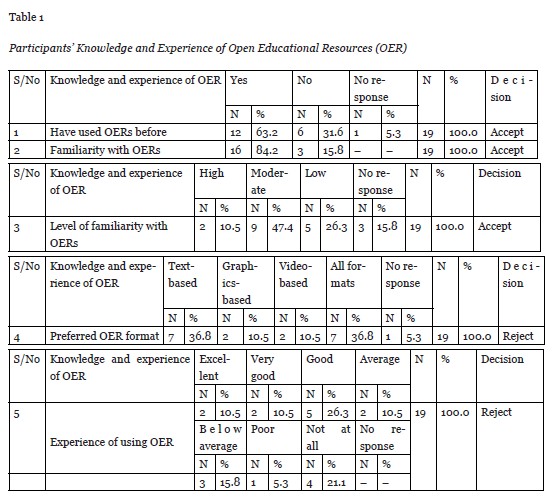

Table 1 reveals that the participants have used OER before (63.2%) and they are very familiar with OER (84.2%). Their level of familiarity is also moderately high (high, 10.5%) and (moderate, 47.4%). However, they have not really used the various formats of OER meaningfully, and this is obvious from their described experience of using OER, which was below the acceptable cutoff point, and was therefore rejected.

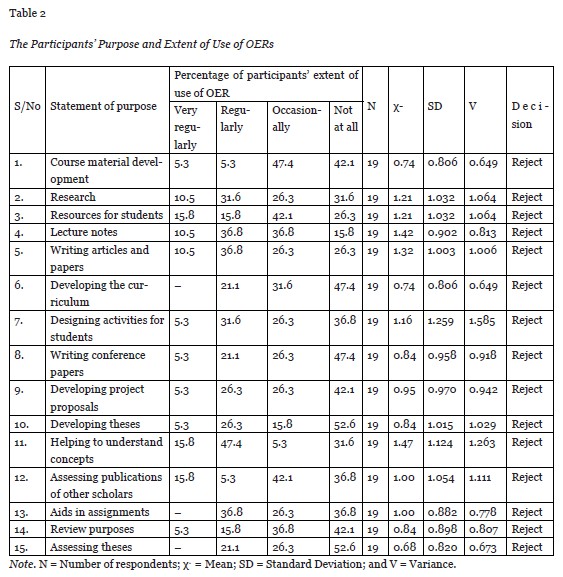

Table 2 shows that none of the fifteen identified purposes for which educators can use OER in teaching and learning were accepted. All the means were below 2.4, the cutoff point for the acceptability of a meaningful response. Participant responses ranged from 0.68 to 1.42. This implies that OER are not yet part of the educational resources used by these academics. This finding was not what I expected based on the various definitions of OER, which opined that the materials are available for educators to use and reuse for teaching, learning, and research, or can be modified and shared to support education (Creative Commons, 2012; Downes, 2011). This result indicates that the participants have yet to benefit from the advantages of the open educational resources in teaching and learning. If instructors at our dual-mode institutions continue to remain at this current level of awareness about OER and their uses, then the objective of using open and distance learning to achieve Education for All and the Millennium Development Goals in Nigeria may not be achieved.

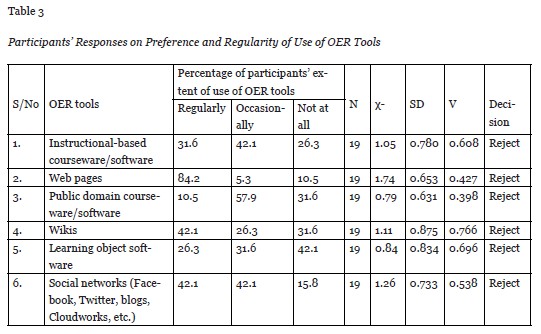

The revelations of Table 3 agree with the earlier observations in Table 2 that Nigerian educators from the dual-mode institutions surveyed in this study have yet to use OER tools as is currently done elsewhere around the globe. Hence, cogent and deliberate action needs to be undertaken urgently to revise this adverse trend in Nigeria’s educational system.

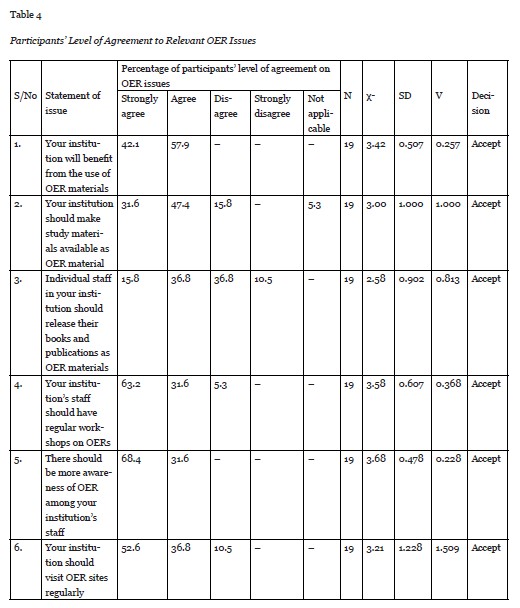

Table 4 indicates the participants’ levels of agreement with relevant OER issues. All the items included in this section of the questionnaire were accepted as meaningful and relevant. This is not surprising since OER are now the global trend, and Nigerians cannot afford to be left behind. In fact, the surveyed educators also have realized there is a need for active involvement in the demands of OER. This is observed in their responses, which ranged from 2.58 to 3.68, that is from moderate (item 2 mean = 3.00; item 3 mean = 2.58) to high mean scores (ranging from 3.32 to 3.68).

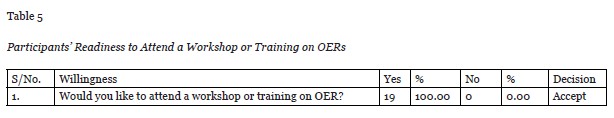

Table 5 needs no further interpretation. Educators from these tertiary institutions practicing dual mode instruction (both conventional face-to-face and open and distance learning) indicated their forward-looking interest and full grasp of what OER could provide; they indicated their 100% willingness and readiness to receive training on OER. This calls for immediate follow-up action through workshops and seminars to further educate teachers in Nigeria about this topic and to actualize this need as a global issue. This will go a long way to enhancing teaching and learning in our changing environment; the emergence of ICT has repositioned ODL and enhanced it with OER.

It is obvious that the capacities of our conventional institutions cannot ensure that the learning needs of our young people and adults will be met. Education for All (EFA) and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have both placed emphasis on the importance of education to economic prosperity. These have brought about open and distance learning (ODL) in Nigeria, a method of instruction which has received a global acceptance. But ODL is highly dependent on self-directed instructional materials as the backbone for course delivery. So far, the realization of a complete ODL program in Nigeria has been greatly challenged by the untimely production of instructional materials (Okonkwo, 2012). Ameliorating this challenge necessitates continuing professional development for educators in ODL. Indeed, OER and the emergence of ICT in education are playing key roles in repositioning educational provision in higher education, especially in ODL scenarios, since it has come to stay in Nigeria as a viable alternative to conventional systems of education. The ODL approach worldwide depends largely on the deployment of OER and the use of technology to thrive and succeed. Hence, effective and efficient implementation of ODL in Nigeria calls for the professional development of educators, who are the backbone of high-level academic institutions. These personnel are needed for the effective delivery of classes and have been introduced in response to strong social demands for access to higher education. However, the results of this study indicate the following.

The paper therefore recommends that there should be training programs covering the rudiments of OER and the ICT skills needed for effective implementation of OER for all educators (both those serving in the conventional systems and those in the open and distance learning environment). This can be done with workshops and seminars for practicing professionals, and the program should be deliberately included in the curriculum for students in Nigerian teacher education institutions.

Alechenu, J. (2012, March 31). 2012 UTME: Only 3 candidates scored above 300 – JAMB. Punch. Retrieved from http://www.punchng.com/news/2012-utme-only-3-candidates-scored-above-300-jamb/

Allen, N. H. (2010, September 1–3). Education for all: Access? Equity? Quality? Presentation for the Standing Conference of Presidents (SCOP) Policy Forum, Pretoria, South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.unisa.ac.za/scop2010/docs/education-for-all_scop2010.pdf

Atkins, D. E., Brown, J. S., & Hammond, A. L. (2007, February). A review of the open educational resources (OER) movement: Achievements, challenges, and new opportunities (Report to the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation). Retrieved from http://www.hewlett.org/uploads/files/ReviewoftheOERMovement.pdf

Bloom, D., Canning, D., & Chan, K. (2006, February). Higher education and economic development in Africa. Washington, DC: Human Development Sector, Africa Region, The World Bank. Retrieved from http://www.arp.harvard.edu/AfricaHigherEducation/Reports/BloomAndCanning.pdf

Creative Commons (2012). What is OER? [Web page]. Retrieved from http://wiki.creativecommons.org/What_is_OER%3F

Daniel, J. (2011, September 11). GLOBAL: New guidelines for open educational resources. University World News. Retrieved from http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20110909190605514

D’Antoni, S. (2009, February). Open educational resources: Reviewing initiatives and issues. Open Learning, 24(1), 3–10.

Das, P. (2010, November). Open education resources and community development: Exploring new pathways of knowledge in the field of higher education in Assam. Paper presented at the Sixth Pan-Commonwealth Forum on Open Learning, Kochi, India.

Downes, S. (2011, July 14). Educational resources: A definition [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://halfanhour.blogspot.ca/2011/07/open-educational-resources-definition.html

Federal Ministry of Education (2002). Blueprint and implementation plan for the National Open and Distance Learning Programme, Nigeria.

Hilton, J., III, Wiley, D., Stein, J., & Johnson, A. (2009). The four R’s of openness and ALMS analysis: Frameworks for open educational resources. Retrieved from https://www.redhat.com/archives/osdc-edu-authors/2011-January/pdfoziqzY4Mtn.pdf

Kanwar, A., Kodhandaraman, B., & Umar, A. (2010, November). If content is king, why are OER still uncrowned? A developing world perspective. Paper presented at the Sixth Pan-Commonwealth Forum on Open Learning, Kochi, India.

Lambert, S. (2004, April 23). Teachers’ pay and conditions: An assessment of recent trends in Africa. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001466/146656e.pdf

Leichty, R. (2012). OER update. Retrieved from www.classroom-aid.com

McAndrew, P. (2010). Fostering open educational practices. ICT in teacher education: Policy, open educational resources, and partnerships. Proceedings of International Conference IITE-2010, St. Petersburg, Russia (pp. 124–129). Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0019/001936/193658e.pdf

NUC (n.d.). National Universities Commission guidelines for open and distance learning in Nigerian Universities. Abuja, Nigeria: National Universities Commission.

Okonkwo, C. A. (2012). Assessment of challenges in developing self-instructional course materials at the National Open University of Nigeria. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(2), 221–230.

Okonkwo, C. A., & Ikpe, A. (2011). Professional development of Science Educators through effective collaboration. Journal of Science Teachers Association of Nigeria, 46(2), 108–118.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2007). Giving knowledge for free: The emergence of open educational resources. Paris: Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, OECD.

Plotkin, H. (2010). Free to learn: An open educational resources policy development guidebook for community college governance officials. San Francisco, CA: Creative Commons. Retrieved from http://wiki.creativecommons.org/images/6/67/FreetoLearnGuide.pdf

Polgreen, L. (2012, January 10). Fatal stampede in South Africa points up university crisis. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/11/world/africa/stampede- highlights-crisis-at-south-african-universities.html?hp

Prozonic, C. (2011, December 31). A Fulbright student seeks a greater voice. Lehigh University News. Retrieved from http://www4.lehigh.edu/news/newsarticle.aspx?Channels/News:+2011WorkflowItemID=3bd2592b-57bc-47c9-9952-73617e95693e

RETRIDAL (2011). Questionnaire on open education resources used by RETRIDAL for National Open University of Nigeria community.

Topkaya, E. Z. (2010). Pre-service English language teachers’ perceptions of computer self-efficacy and general self-efficacy. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 9(1), 143–156.

UNESCO (2011). Global education digest: Comparing education statistics across the world. Montreal, QC: Institute for Statistics of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved from http://www.uis.unesco.org/Library/Documents/global_education_digest_2011_en.pdf

United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. New York, NY: Author. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/

United Nations. (2009). The Millennium Development Goals report 2009. New York, NY: Author. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/MDG_Report_2009_ENG.pdf

Wiley, D. (2009, November 16). Defining open. [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/1123

World Bank. (2010). Directions in development: Human development—Financing higher education in Africa. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EDUCATION/Resources/278200-1099079877269/Financing_higher_edu_Africa.pdf

Wright, C. R., & Reju, S. A. (2012). Developing and deploying OERs in sub-Saharan Africa: Building on the present. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(2), 181–220.