|

|

|

|

Paul Gorsky, Avner Caspi, Ina Blau, Yodfat Vine (not shown) and Amit Billet

Open University of Israel

The goal of this study is to further corroborate a hypothesized population parameter for the frequencies of social presence versus the sum of teaching presence and cognitive presence as defined by the community of inquiry model in higher education asynchronous course forums. This parameter has been found across five variables: academic institution (distance university vs. campus-based college), academic discipline (exact sciences vs. humanities), academic level (graduate vs. undergraduate), course level (introduction vs. regular vs. advanced), and course size (small vs. medium vs. large), that is, the number of students enrolled. To date, the quantitative content analyses have been carried out using the syntactic unit of message. In an attempt to further establish the parameter’s goodness-of-fit, it is now tested across two different syntactic units, message versus sentence. To do so, the same three-week segments from 15 Open University undergraduate course forums (10 from humanities and five from exact sciences) were analyzed twice—once by the unit message and once by the unit sentence. We found that the hypothesized parameter remained viable when the unit of analysis is the sentence. We also found that the choice of syntactic unit is indeed a critical factor that determines the “content” of the transcript and its inferred meaning.

Keywords: Higher education; asynchronous forums; protocol analysis; community of inquiry model; quantitative content analysis; syntactic units

We first present a brief overview of the research carried out. Concepts and variables mentioned here will be elaborated upon and placed in a more explicit perspective further below.

The community of inquiry framework has become an accepted and widely used model that describes teaching and learning in online and blended learning environments. The model assumes three dimensions or presences (social presence, teaching presence, and cognitive presence), through which dialogic behavior (verbal interactions) may be categorized. Considerable research has been conducted using the framework (Akyol et al., 2009). One particular line of inquiry, carried out by Gorsky and his colleagues (Gorsky, 2011; Gorsky & Blau, 2009; Gorsky, Caspi, Antonovsky, Blau, & Mansur, 2010; Gorsky, Caspi, & Blau, 2011), has been the search for recurrent patterns in the frequencies of social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence in higher education, asynchronous course forums. To date, a ratio for the frequencies of “social presence” (the sum of its three categories) versus the sum of “teaching presence” and “cognitive presence” (the sum of their combined seven categories) has been calculated. This ratio (61.75%:38.25%) has been found stable across five variables: academic institution (distance university vs. campus-based college), academic discipline (exact sciences vs. humanities), academic level (graduate vs. undergraduate), course level (introduction vs. regular vs. advanced), and group size (small vs. medium vs. large), that is, the number of students enrolled. Given the recurrence of this ratio, we suggest that it may represent a population parameter that holds for higher education asynchronous course forums.

To date, the quantitative content analyses that established the parameter have been carried out using the syntactic unit of a message. The first objective of this investigation is to further corroborate the parameter’s viability, that is, its goodness-of-fit, across two different units of analysis, message and sentence. To do so, we analyze the same 15 forums twice, first by message then by sentence.

The second objective of this investigation is to document similarities and differences that emerge from using two different analytic procedures on the same protocols. Although the importance of selecting an appropriate unit of analysis has been noted (Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, & Archer, 2001), to the best of our knowledge, no research has been carried out which shows the explicit costs and benefits associated with each procedure in the manner we propose. Furthermore, De Wever, Schellens, Valcke, and Van Keer (2006, p. 19) criticized current reporting practices, noting that “most authors do not mention arguments for selecting or determining the unit of analysis.” We hope to provide criteria for selecting either sentences or messages as the unit of analysis.

In the following two sections, we summarize the research that led to the discovery of the hypothesized parameter and the research into the impact of unit of analysis on the outcomes of content analysis. We will not discuss the community of inquiry model. Readers unfamiliar with the model are referred to the Web site (http://www.communitiesofinquiry.com).

A parameter is a number (or set of numbers) that describes a particular characteristic of a given population. The population under question in this ongoing research project is the set of all higher education asynchronous course forums, university and college, both distance and campus-based. The characteristic being investigated is the ratio of “social presence” versus the sum of “teaching presence” and “cognitive presence.”

We believe that this particular ratio is meaningful for two reasons. First, whatever the setting (e.g., institution type, academic discipline, course level, etc.), rates of social presence (calculated from different samples) distribute closely around a hypothesized parameter. Second, although individual rates of teaching presence and cognitive presence vary within different settings, their sum also distributes closely around a hypothesized parameter.

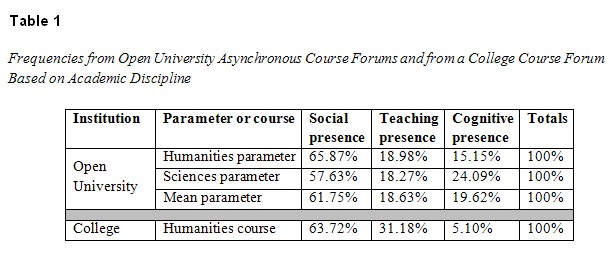

The hypothesized population parameter emerged from a study (Gorsky et al., 2010) that analyzed three-week segments from 50 undergraduate course forums, 25 from exact sciences and 25 from humanities, at the Open University of Israel using the quantitative content analysis technique (Rourke et al., 2001) derived from the community of inquiry model (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000). The initial goal of that study was to determine the impact of academic discipline (exact science vs. humanities) on dialogic behavior in course forums. For both disciplines, frequencies of teaching presence, cognitive presence, and social presence were calculated. Findings pointed toward two distinct distributions, one for each discipline. The individual frequencies, as well as their mean frequency, are shown in Table 1.

Further analysis (Gorsky et al., 2010) showed that, in addition to academic discipline, the mean frequencies were constant across the variables course level (introductory, regular, advanced), academic level (undergraduate and graduate courses), and group size (small, medium, large), that is, the number of students enrolled. At this point, it was proposed that these three frequencies might represent actual population parameters.

An additional study (Gorsky et al., 2011) was carried out to corroborate the existence of these frequencies at a different kind of institution for higher education, namely a campus-based college which also routinely used asynchronous course forums as an instructional resource. We carried out quantitative content analysis on an entire year-long, two-semester humanities course. We compared these frequencies with those obtained from the Open University. Findings (Table 1) showed that the frequencies for each of the three presences differed significantly at each institution (for in-depth statistical analyses and for an explanation as to how and why rates of cognitive presence and teaching presence differed, see Gorsky et al., 2011). However, the similar rates of social presence for the forums in both institutions (Table 1) are striking.

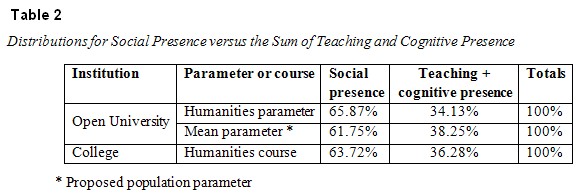

Table 2 shows an alternate representation of the data shown in Table 1. In this format, there is no significant difference between the frequencies from the campus-based college course forum and the frequencies from the Open University humanities forums and the frequencies for the mean parameter (the proposed population parameter). It was also noted by Gorsky (2011) that the proposed population parameter (61.75:38.25) approximates the Golden Ratio with 99.75% precision.

Content analysis has been defined as “any technique for making inferences by objectively and systematically identifying specified characteristics of messages” (Holsti, 1969, p. 14). To date, content analysis is characterized by two separate but complementary methodologies, quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative methodologies generally code and summarize communications. Frequencies, which serve as a basis for comparison and statistical analysis, are often calculated. Qualitative methodologies are generally grounded in interpretive paradigms that attempt to identify major themes or categories within a transcript or protocol and to describe the social reality derived from those themes or categories in a particular setting.

A great deal of research in protocol analysis, both within and outside the community of inquiry model, has been carried out using different units of analysis. Associated with qualitative content analysis, Henri (1992) used a thematic unit. Murphy and Ciszewska-Carr (2005) pointed out that Henri’s thematic unit was later adopted in a number of other studies (they cited Aviv, 2001; Gunawardena, Lowe, & Anderson, 1997; Howell-Richardson & Mellar, 1996; Jeong, 2003; McDonald, 1998; Newman, Webb, & Cochrane, 1995; Turcotte & Laferrière, 2004). Associated with quantitative content analysis, Hara, Bonk, and Angeli (2000) used a paragraph; Aviv, Erlich, Ravid, and Geva (2003) and Gorsky (2011) and Gorsky and colleagues (2009, 2010, 2011) used the entire message; Fahy (2001, 2002) and Poscente and Fahy (2003) chose the sentence.

These researchers chose units of analysis in accord with their research objectives. For example, Poscente and Fahy (2003) sought to identify strategic initial sentences (triggers) in computer conferencing transcripts. In line with this objective, the sentence is obviously the best unit of analysis. Aviv et al. (2003) analyzed transcripts by message in an attempt to understand the collaborative process in asynchronous course forums. They innovatively assigned more than one code to a message if it included more than one type of behavior. Gorsky (2011) and his colleagues (2009; 2010; 2011), in their search for recurrent patterns in the frequencies of social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence, chose the message unit since it combines a high-level overview of the dialogic behavior in course forums with very high rates of inter-rater reliability. They also assigned more than one category to an entire message.

When selecting syntactic message units, Rourke et al. (2001) cited four important criteria that should be taken into account. First, the unit must be “objectively identifiable”; that is, different raters can agree consistently on the total number of cases and who posted each case. The ability to identify units reliably increases with the size of the syntactic unit. Given the nature of archived transcripts, a message can be identified as such with 100% reliability. Identifying a paragraph or sentence may be problematic. For example, Rourke et al. (2001, p. 16) noted difficulty in identifying sentences. The syntax in the conferences they studied “combined a telegraphic writing style with the informality of oral conversation.” An example from their paper follows:

Certain subjects could be called training subjects . . . i.e. How to apply artificial respiration. . . . as in first aid . . . and though you may want to be a guide on the side. . . . one must know the correct procedures in order to teach competency . . . other subjects lead themselves very well to exploration and comment/research . . .

Second, the unit should generate “a manageable set of cases.” Murphy and Ciszewska-Carr (2005, p. 549) noted that “the choice of a sentence as a unit of analysis may prove problematic with long and multiple transcripts.” Rourke et al. (2001) reported that participants in their study wrote more than 2,000 sentences during a 13-week discussion. They deemed this “an enormous amount of cases.”

Third, the unit should yield relatively high rates of “inter-rater reliability.” More than 30 years ago, Saris-Gallhofer, Saris, and Morton (1978) found that shorter coding units, such as words, yielded higher reliability than longer units, such as sentences or paragraphs. On the other hand, Insch, Moore, and Murphy (1997) noted that choosing too small a unit may result in obscuring subtle interpretations of statements in context.

Fourth, the unit should possess “discriminant capability”; that is, the structure of the unit should enable the researcher to discriminate between the different constructs being observed. Rourke et al. (2001, p. 11) noted that fixed syntactic units “do not always properly encompass the construct under investigation.”

Using these four criteria, we attempt to determine the impact of unit of analysis on the results of content analysis, that is, on the frequencies measured by each.

As noted, the goals of this study are twofold: (a) to validate the hypothesized population parameters by using an alternative analytic procedure; and (b) to investigate the impact of unit of analysis (message vs. sentence) on the results of content analysis, that is, the frequencies of the different presences. If the parameter is not viable (i.e., low goodness-of-fit as determined by chi square statistics) for the same forums analyzed twice, once by message and a second time by sentence, then it is an artifact of a very specific analytic procedure and its significance is limited, at best, and meaningless, at worst. If the hypothesized parameter holds (that is, there is no significant difference between the frequencies for social presence and the sum of teaching presence and cognitive presence) across academic discipline, academic institution, academic level, course level, group size (the number of students enrolled), and syntactic unit, then this study is another small, but possibly meaningful step toward finding a population parameter for higher education asynchronous course forums. Such a parameter might be named the community of inquiry constant or CoI constant.

Rourke et al. (2001) noted the importance of selecting the unit of analysis when doing content analysis of this particular type. Almost every research paper that uses the quantitative content analysis procedure to study communities of inquiry cites this reference; however, to the best of our knowledge, no findings have been reported as to the actual differences obtained when the two procedures are applied to the same forum or forums. The operational research questions being asked are framed in the criteria suggested by Rourke et al. (2001). When comparing content analyses carried out on the same transcripts with two different units of analysis, sentence versus message:

a. What are the overall distributions of “social presence,” “teaching presence,” and “cognitive presence” and what are the distributions across different disciplines? In other words, will these two distributions differ significantly when analyzed by sentence and message?

b. What are the distributions of “social presence,” “teaching presence,” and “cognitive presence” for instructors and for students, both overall and across different disciplines?

Finally, regarding the hypothesized parameters, we ask:

In other words, will these distributions differ significantly from the hypothesized (two-dimensional) population parameter and humanities parameter?

The Open University of Israel is a distance education university that offers undergraduate and graduate studies to students throughout Israel. The learning environment is blended: The University offers a learning method based on printed textbooks, face-to-face tutorials, and an online learning content management system (LCMS) wherein each course has its own Web site. Course sites simplify organizational procedures and enrich students’ learning opportunities and experiences. Web site use is optional, non-mandatory so that equality among students is preserved. It does not replace textbooks or face-to-face tutorials, which are the pedagogical foundations of the Open University. The Web site provides forums for asynchronous instructor-student and student-student interactions. Each course has a coordinator, who is responsible for all administrative and academic activities, and instructors, who lead tutorials. Instructors and coordinators are available for telephone consultations at specified days and times.

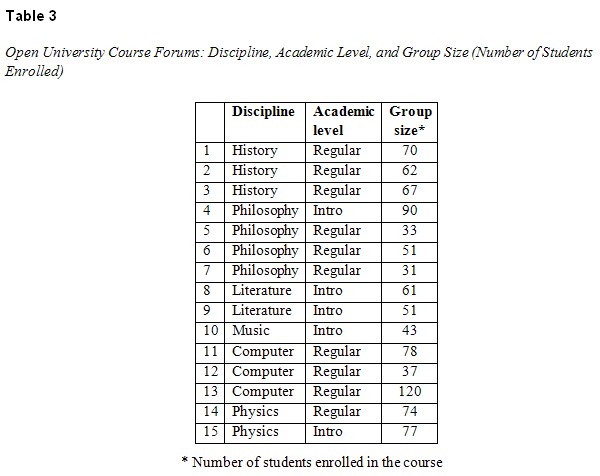

We analyzed three-week segments from 15 undergraduate Open University course forums, 10 from the humanities and five from the exact sciences. The trial period began one month after the start of the semester in order to insure that opening messages and initial enthusiasm had waned and that the final exam was still far distant. Participation in all forums was non-obligatory; no grades or bonuses were linked to student participation. Courses are shown in Table 3.

The quantitative content analysis technique was used to code and analyze transcriptions from the forum. This technique has been widely used; when used properly, it is reliable and valid (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007). We will discuss here both the technique and the technicians (those who carried out the content analyses). Regarding the technique, several issues must be dealt with.

The first issue is the unit of analysis. In this study, two different syntactical units of analysis were used, message and sentence. Indeed, it is the outcomes of this distinction that are being investigated.

A second issue is the level of coding (e.g., indicator vs. category). Content analysis, as described by Rourke and Anderson (2004), is time-consuming, and coding at the indicator level is difficult, often yielding poor reliability (Murphy & Ciszewska-Carr, 2005). In this study, as in the previous ones (Gorsky, 2011, Gorsky & Blau, 2009; Gorsky et al., 2010, Gorsky et al., 2011), coding was at the category level in order to obtain a reliable, high-level overview of dialogic behavior.

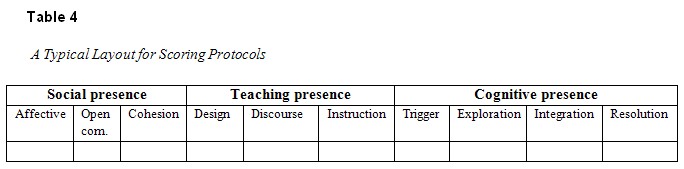

A third issue is scoring. As in the previous studies cited above, we analyzed each unit, message or sentence, and scored each of the 10 categories as either present or not present (1 or 0). In other words, if a category occurred more than once in a given message or a given sentence (say, two distinct occurrences of “open communication”), we recorded present only once. We did not count multiple recurrences of a category within the same message or sentence. Codes were recorded in a spreadsheet. Each row is a syntactic unit, either message or sentence, all of which were numbered. Table 4 shows a typical layout.

The rationale for this scoring method is simple: When analyzing a message, it is taken in its entirety; for example, either the category “cohesion” is present or not. If it is present more than once, then it is present in an additional sentence. In other words, such analysis would be taking place at the level of sentence, not message. In a similar manner, when analyzing a sentence, it too is taken in its entirety; either the category “cohesion” is present or not. If it is present more than once, then it is present in an additional clause, either dependent or independent. In other words, such analysis would be taking place at the level of sentence clauses, or even words, not sentences.

Regarding the technicians, those who analyzed and coded the transcripts, we describe briefly how they were selected and prepared for the task at hand. Four different raters took part in this study: Rater A (third author) is a senior faculty member at the Open University of Israel and an expert in the field of quantitative content analysis. She trained raters B, C (fourth author), and D (fifth author), who were graduate students working toward their degrees in educational technology. Training included participation in a three-hour workshop that dealt with the theoretical basis of the CoI model and with the practical applications of quantitative content analysis. After the seminar, the trainees analyzed transcripts until they reached high inter-rater agreement with the instructor, Rater A.

Raters A and B analyzed messages in a study whose findings were reported by Gorsky et al. (2010); these findings had no relationship at all with the findings presented here. Raters C and D analyzed the same protocols, by sentence. They were aware that their findings would be compared with those obtained from analysis by message. Given the very large number of sentences analyzed, such awareness could have no possible impact on their coding.

Three-week segments from 15 Open University undergraduate course forums (10 from humanities and five from exact sciences), were analyzed twice, once by message, once by sentence. The 15 forums included 664 messages composed of 3,243 sentences. Findings are presented in accord with the research questions asked.

1. To what extent are sentences “objectively identifiable” as such?

In order to overcome any potential difficulties involved with identifying sentences, two raters worked together as suggested by Rourke et al. (2001). They agreed upon the syntactical structure of the entire transcript prior to the content analysis and reliability check. They did so based on the following guidelines, which we defined:

Given these guidelines, close to full agreement was achieved. For about 30 sentences (about 1% of the total), discussion resolved any lack of agreement.

2. What is the ratio of sentences to messages?

The ratio of sentences to messages is 4.88:1. In other words, content analysis by sentence requires about five times the effort needed to analyze the identical transcripts by message. Messages in the humanities had 23.50% more sentences than their counterparts in the exact sciences. This does not necessarily indicate greater verbosity (words were not counted), only that humanities students wrote more sentences, whatever their length.

3. What is the impact on “inter-rater reliability”?

Twenty-five percent of postings were randomly chosen and re-estimated by a second rater. Ninety-two percent agreement was recorded (Cohen’s κ = 0.89) for the 15 forums analyzed by message; 95% agreement was recorded (Cohen’s κ = 0.91) for the 15 forums analyzed by sentence.

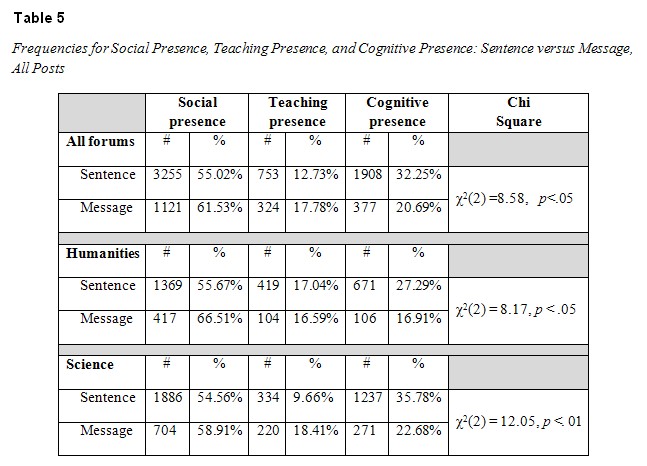

4a. What are the overall distributions of “social presence,” “teaching presence,” and “cognitive presence” and what are the distributions across different disciplines? In other words, how does the unit of analysis affect “discriminant capability”? Table 5 presents these findings.

As seen from the data in Table 5, there were statistically significant differences between each of the distributions. In other words, different analytic procedures, based on the unit of analysis, yielded different results. When analyzed by sentence, as opposed to message, forums in the humanities were characterized by increased cognitive presence and reduced social presence. Forums in the sciences were characterized by increased cognitive presence and reduced teaching presence.

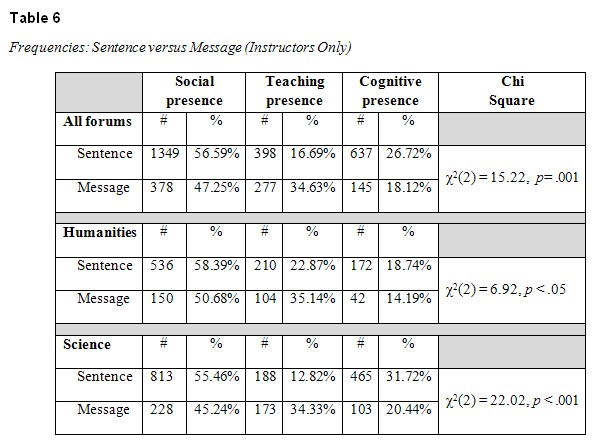

4b. What are the distributions of “social presence,” “teaching presence,” and “cognitive presence” for instructors and for students, both overall and across different disciplines? These findings also reflect the “discriminant capability” of each unit of analysis. Data based on postings made by instructors only are presented in Table 6.

As seen from the data in Table 6, the distributions differ significantly. When analyzed by sentence, as opposed to message, the dialogic behavior of instructors in the humanities and sciences was similar: reduced teaching presence and increased cognitive presence and social presence.

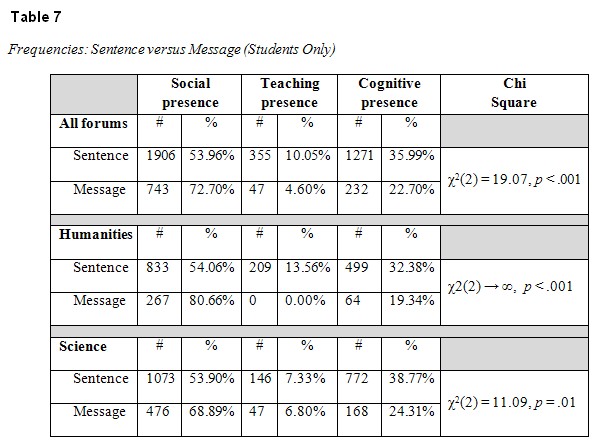

Next, we analyzed the distributions based on postings made by students only. Findings are shown in Table 7.

Again, as seen from the data in Table 7, there are highly significant statistical differences between each of the distributions. When analyzed by sentence, as opposed to message, the dialogic behavior of students in the humanities was characterized by highly reduced social presence and increased cognitive presence and teaching presence. Students’ dialogic behavior in the sciences was characterized by reduced social presence and increased cognitive presence. Teaching presence remained about the same.

One specific finding in Table 7 is highly anomalous, namely no recorded incidents of students’ teaching presence in the humanities were recorded when the protocols were analyzed by message. When the same protocols were analyzed by sentence, 209 incidents were recorded. This anomaly will be addressed below in the Discussion section.

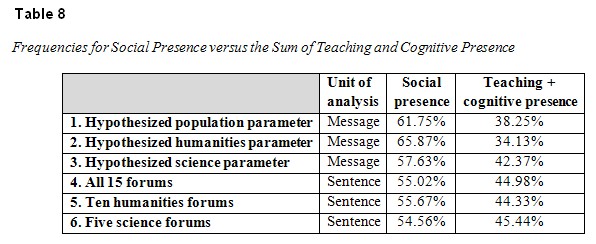

Finally, in order to corroborate the three hypothesized parameters (population parameter, humanities parameter, and science parameter) across units of analysis, we calculated the overall distributions of “social presence” versus the sum of “teaching presence” and “cognitive presence” for the same forums, analyzed first by message and then by sentence. Table 8 presents these findings.

No significant differences were found for the following parameters (analyzed by message) and the following forums (analyzed by sentence):

Borderline difference between the hypothesized humanities parameter and the 10 humanities forums was noted (χ2(1) = 3.81, p = .05).

In other words, the hypothesized population parameter (calculated by analyzing messages) is viable or compatible with the same ratios obtained from forums calculated by analyzing sentences.

We asked two broad research questions. First, do the hypothesized parameters for the frequencies of “social presence” versus the sum of “cognitive presence” and “teaching presence” in higher education asynchronous forums remain viable when different units of analysis are used? Second, what is the impact of unit (sentence vs. message) on the results of quantitative content analysis; that is, what similarities and differences emerge when the same forum is analyzed using different units of analysis, message and sentence? We begin with the latter issue.

The Impact of Unit (Sentence vs. Message) on the Results of Quantitative Content Analysis

We will discuss the outcomes of the content analyses in terms of the four criteria noted by Rourke et al. (2001).

1. Both procedures yielded “objectively identifiable” units. Although messages are automatically identified as such, sentences were also relatively easily identified and mutually agreed upon by the raters before the start of the analyses. For whatever reasons, students generally wrote sentence-based text and did not use a telegraphic writing style associated with the informality of oral conversation as reported by Rourke et al. (2001). This criterion, therefore, need not be an obstacle that prevents the use of the sentence as a reliable and valid unit of analysis.

2. High rates of “inter-rater reliability” were achieved in both analyses, by sentence (95% agreement) and by message (92% agreement). Again, this is not a restrictive factor.

At this point, we will discuss the anomalous findings noted in Table 7. (No recorded incidents of students’ teaching presence in the humanities were recorded when the protocols were analyzed by message. When the same protocols were analyzed by sentence, 209 incidents were recorded.) We suggest that these findings are related to inter-rater reliability and that they do not change the findings reported here in any statistically significant way. We now review the process of content analysis and its accompanying inter-rater reliability test.

As noted above, four raters were employed. Rater B analyzed the protocols by message; Rater A re-estimated 25% of postings that were randomly chosen. Ninety-two percent agreement was recorded (Cohen’s κ = 0.89). Rater C analyzed the protocols by sentence; Rater D re-estimated 25% of postings that were randomly chosen. Ninety-five percent agreement was recorded (Cohen’s κ = 0.91).

We suggest two possible explanations for the apparent discrepancies. First, high rates of agreement were scored between raters A and B and between raters C and D. No such reliability tests were carried out between raters A and C. In retrospect, it may have been preferable to have used one pair of raters only for both content analyses (sentence and message). This would have assured a uniformly high rate of inter-rater reliability. The downside of this procedure, however, would be in the creation of a potential prejudicial cross-over problem since the raters would be rescoring the same texts they had already reviewed.

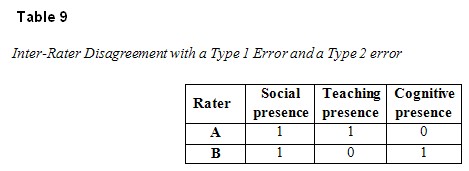

Second, to account for the “disappearance” of incidents of teaching presence from the messages of humanities students, we reviewed the reliability check between raters A and B. We found a total of 44 instances of inter-rater disagreement between cognitive presence and teaching presence that occurred in the same message. Such disagreement means that a type 1 error and a type 2 error occurred in the same message. To illustrate, Table 9 shows two disagreements between raters A and B in the same message.

In retrospect, had rater A performed the entire content analysis and rater B the reliability test, 13 incidents of students’ teaching presence would have been noted (as opposed to the current value of zero). Statistically, whether there are 13 incidents of students’ teaching presence or zero incidents, the difference is insignificant and can be attributed to reasonable fluctuations in inter-rater agreement and disagreement.

3. There were nearly five sentences per message (4.88:1). Is this “a manageable set of cases”? There should be very compelling reasons to invest nearly five times the time, effort, and cost to analyze by sentence.

4. Such reasons may be found in terms of the criterion “discriminant capability” (Rourke et al., 2001). Tables 6 and 7 show the frequencies of the three presences for instructors and for students. For instructors in the humanities, when analyzed by sentence as opposed to message, their transcripts indicate about a 35% decrease in teaching presence. In a similar manner, for instructors in the sciences, when analyzed by sentence, their transcripts indicate about a 63% decrease in teaching presence. For researchers investigating the perceived or “objective” impact that results from instructors’ teaching presence on the dialogic behavior of course forums, these findings appear to be especially meaningful. These findings will be noticeable if and only if the unit of analysis is the sentence where the resolution is five times greater than that of the message. Clearly, given the scoring procedure based on present/not present, additional categories are revealed when forums are analyzed sentence by sentence.

For instructors in the sciences, when analyzed by sentence, their transcripts indicate about a 55% increase in cognitive presence. Again, this finding seems straightforward: Messages from instructors may often include many different ideas expressed in multiple sentences. For researchers investigating the factors associated with the extent and nature of instructors’ cognitive presence in communities of inquiry, these findings may be especially meaningful. Rates of cognitive presence for instructors in the humanities were similar for both units of analysis. These low rates of cognitive presence in humanities forums were described by Gorsky et al. (2010).

For students in both disciplines, social presence was diminished when protocols were analyzed by sentence. Social presence for science students was about 22% less and for humanities students about one third less. This makes sense since social presence is often laconic (e.g., “Hi, all,” “I was thinking the same thing,” etc.) and at higher resolutions, sentence by sentence, is diminished. Again, for researchers investigating the nature of students’ social presence and its relationship to other presences as well as to “perceived learning,” these findings appear to be especially meaningful.

For students in both disciplines, cognitive presence increased by about 50% when protocols were analyzed by sentence. This finding reflects the notion that ideas are often expressed in multiple sentences. Furthermore, it hints at collaborative learning where students aid and abet their fellow students. Such collaborative behavior has been reported by Caspi and Gorsky (2006), Gorsky, Caspi, and Trumper (2004, 2006), and Gorsky, Caspi, and Tuvi-Arad (2004).

In summation, it would seem that researchers seeking causal relationships among the three presences have exceptionally good reasons to analyze by sentence despite the additional burden in time and cost. A large amount of useful data, unobservable when transcripts are analyzed by message, suddenly becomes available.

The two-dimensional ratio (61.75:38.25), the hypothesized population parameter, was found viable for both units of analysis, message and sentence. This is truly surprising given the kinds of changes in dialogic behavior exhibited by instructors (Table 6) and students (Table 7) when analyzed by the different units of analysis. In the wake of this study, this parameter has been found to be constant across six variables: academic institution (distance university vs. campus-based college), academic discipline (exact sciences vs. humanities), academic level (graduate vs. undergraduate), course level (introduction vs. regular vs. advanced), group size (small vs. medium vs. large), that is, the number of students enrolled, and unit of analysis (sentence vs. message). In order to approach some understanding as to what a population parameter means in the framework of this research, we return to some first premises and look again at the nature of content analysis itself.

To begin, we reiterate the obvious, namely, that the results of any content analysis, or any scientific inquiry whatever the discipline, are dependent upon its theoretical base and the selected methodology that includes a particular unit of analysis. Clearly, findings are the outcome of particular decisions that determined the questions asked and the analytical tools used. This was noted by Heisenberg (1958), one of the founders of quantum theory: “We have to remember that what we observe is not nature herself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.”

Thus said, the hypothesized parameters are relevant only for the given theoretical base (community of inquiry model, Garrison et al., 2000) and for the given methodology (quantitative content analysis, Rourke et al., 2001) that encompasses two units of analysis, message and sentence. Within these restraints, the hypothesized population parameter may be named the community of inquiry constant or the CoI constant.

Once again, before continuing on, we wish to emphasize that the parameters and/or CoI constant and/or symmetry inferred from these and previous findings are, at best, extremely tentative. In order to more fully support the parameter, first and foremost, corroborative research needs to be carried out. In addition, research needs to be carried out in a wider context that may include different learning environments, different coding processes, and different coders not trained by the third author. We have, however, pointed to the intriguing possibility that such a parameter may exist.

To conclude, we will momentarily suspend disbelief and attempt to assign meaning to this parameter, as if it does indeed exist. First and foremost, any parameter, constant, or symmetry in the behavioral sciences is rare. This hypothesized parameter describes symmetry between social presence and the sum of cognitive and teaching presence in certain kinds of communities of inquiry. Regarding behaviors associated with teaching and learning, we are social beings, and this essence is expressed in the parameter: Our social nature (“social presence”) is in a fixed proportion with the nature of teaching and learning (“teaching presence” and “cognitive presence”). And . . . social presence outweighs the sum of teaching presence and cognitive presence.

Akyol, Z., Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2009). A response to the review of the community of inquiry framework. Journal of Distance Education, 23, 123–136.

Aviv, R. (2001). Educational performance of ALN via content analysis. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 4, 53–72.

Aviv, R., Erlich, Z., Ravid, G., & Geva, A. (2003). Network analysis of knowledge construction in asynchronous learning networks. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7, 1–23.

Caspi, A., & Gorsky, P. (2006). Open University students’ use of dialogue. Studies in Higher Education, 31(6), 735–752.

De Wever, B., Schellens, T., Valcke, M., & Van Keer, H. (2006). Content analysis schemes to analyze transcripts of online asynchronous discussion groups: A review. Computers and Education, 46, 6–28.

Fahy, P. J. (2001). Addressing some common problems in transcript analysis. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 1. Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/321/530

Fahy, P. J. (2002). Epistolary and expository interaction patterns in a computer conference transcript. Journal of Distance Education, 17, 20–35.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2, 87–105.

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Education, 10, 157–172.

Gorsky, P. (2011). Hidden structures in asynchronous course forums: Toward a golden ratio population parameter. In Proceedings of Ninth International Conference on Computer Supported Collaborative Learning: Connecting Computer Supported Collaborative Learning to Policy and Practice. Center for Information Technology in Education, University of Hong Kong.

Gorsky, P., & Blau, I. (2009). Effective online teaching: A tale of two instructors. International Review of Research on Distance Learning, 10(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/712/1270

Gorsky, P., Caspi, A., Antonovsky, A., Blau, I., & Mansur, A. (2010). The relationship between academic discipline and dialogic behavior in Open University course forums. International Review of Research on Distance Learning, 11(2). Retrieved fromhttp://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/820/1546

Gorsky, P., Caspi, A., & Blau, I. (2011). Communities of inquiry in higher education asynchronous course forums: Toward a population parameter. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Gorsky, P., Caspi, A., & Trumper, R. (2004). Dialogue in a distance education physics course. Open Learning: The Journal of Open and Distance Learning, 19(3), 265–277.

Gorsky, P., Caspi, A., & Trumper, R. (2006). Campus-based university students’ use of dialogue. Studies in Higher Education, 31(1), 71–87.

Gorsky, P., Caspi, A., & Tuvi-Arad, I. (2004). Use of instructional dialogue by university students in a distance education chemistry course. Journal of Distance Education, 19(1), 1–19.

Gunawardena, C., Lowe, C. A., & Anderson, T. (1997). Analysis of a global online debate and the development of an interaction analysis model for examining social construction of knowledge in computer conferencing. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 17, 397–431.

Hara, N., Bonk, C. J., & Angeli, C. (2000). Content analyses of on-line discussion in an applied educational psychology course. Instructional Science, 28, 115–152.

Heisenberg, W. (1958). Physics and philosophy: The revolution in modern science. Lectures delivered at University of St. Andrews, Scotland, Winter, 1955–56. New York: Harper and Row.

Henri, F. (1992). Computer conferencing and content analysis. In A. R. Kaye (Ed.), Collaborative learning through computer conferencing (pp. 117–136). Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Howell-Richardson, C., & Mellar, H. (1996). A methodology for the analysis of patterns of interactions of participation within computer mediated communication courses. Instructional Science, 24, 47–69.

Insch, G., Moore, J. E., & Murphy, L. D. (1997). Content analysis in leadership research: Examples, procedures, and suggestions for future use. Leadership Quarterly, 8, 1–25.

Jeong, A. C. (2003). The sequential analysis of group interaction and critical thinking in online threaded discussions. American Journal of Distance Education, 17, 25–43.

McDonald, J. (1998). Interpersonal group dynamics and development in computer conferencing: The rest of the story. In Proceedings of the 14th conference on distance teaching and learning. Madison, WI: Continuing and Vocational Education, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Murphy, E., & Ciszewska-Carr, J. (2005). Contrasting syntactic and semantic units in the analysis of online discussions. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 21, 546–566.

Newman, D. R., Webb, B., & Cochrane, C. (1995). A content analysis method to measure critical thinking in face-to-face and computer supported group learning. Interpersonal Computing and Technology Journal, 3, 56–77.

Poscente, K. R., & Fahy, P. J. (2003). Investigating triggers in CMC text transcripts. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 4(2). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/content/v4.2/poscente_fahy.html

Rourke, L., & Anderson, T. (2004). Validity issues in quantitative computer conference transcript analysis. Educational Technology Research and Development, 52, 5–18.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Methodological issues in the content analysis of computer conference transcripts. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 12, 8–22.

Saris-Gallhofer, I. N., Saris, W. E., & Morton, E. L. (1978). A validation study of Holsti’’s content analysis procedure. Quality and Quantity, 12, 131–145.

Turcotte, S., & Laferrière, T. (2004). Integration of an online discussion forum in a campus-based undergraduate biology class. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 30, 73–92.