Dianne Conrad

Athabasca University, Canada

Within the practice of recognizing prior learning (RPL), language issues – writing, the act of capturing language – are critically important facets of portfolio development. Using data drawn from a study of several postsecondary institutions in three countries, this paper examines the role and impact of language in portfolio development processes. Specifically, it considers the dynamics that contribute to learners’ finding appropriate language and their response to that journey, noting that learners pass through several stages of language growth, beginning with learning the language of academic life and recognizing the importance of that “new” language. The paper also discusses the impact of assessors’ use of language and considers the notion of learners’ transformation as they pass through the portfolio learning process.

Keywords: Prior Learning Assessment; RPL

We are aware in university RPL 1practice of issues of power, pedagogy and protocols in portfolio preparation and assessment processes. Even the well-intentioned action of mentoring learners through their preparation process holds the potential of bias or some type of power differential at play between student and coach (Conrad & Wardrop, 2010; Harris, 2000; Peters, 2006). Perhaps not so obviously, issues of language – especially writing, the act of capturing language – are also critically important facets of portfolio development. This paper examines the role and impact of language in portfolio development processes. Specifically, it will consider the dynamics that contribute to learners’ finding appropriate language and their response to that journey. The paper combines preliminary data from an ongoing study and from the literature.

Some initial assumptions must be made clear. This discussion assumes that no language barrier of ethnic origin or basis exists between learners and institutions. Of course that will not always be the case, but the argument put forth here does not rest on or arise from the presence of a basic language barrier. Research data did not reveal any such language barriers among the study’s participants. The discussion also assumes a portfolio process that requires learners to construct written material, often extensive, that is designed to demonstrate their knowledge of or proficiency in certain areas of expertise. Such a detailed process both encourages and permits learners to learn about their own learning and about themselves in addition to developing new skills in areas of thinking and organizing. For this reason, the term portfolio learning is used here. The paper will describe such a process following a description of the research study. 2

The study that gave rise to this language discussion investigated how learners approached and experienced their own learning while engaged in university-level RPL processes and how those who assisted learners with their RPL processes perceived the effects of their respective approaches in terms of cognition, affect, and outcomes. In other words, this study examined several RPL processes and the learning-centred experiences of individuals within those processes.

The study’s objectives were informed by the central research question: To what extent and in what ways do RPL processes contribute to or encourage learners’ ability to build knowledge? From the exploration of that central question, data that addressed language issues relative to learners’ building knowledge emerged. Those data contribute to this paper. Other findings from the study will be addressed separately as the study concludes.

The study’s qualitative research design included RPL learners, mentors, advisors, faculty, and administrators from four Canadian institutions, four American institutions, and two Scottish institutions. Scotland was chosen as an international location because of its system’s position within a national qualifications framework (SNQF). Participants included learners who were currently engaged in a prior learning process, learners who had completed RPL within the last year, and administrative and faculty participants who were currently working with RPL learners or who had a history of RPL association.

The researcher sought to cast a wide net to explore RPL participants’ experiences in knowledge creation and learning in institutions that practiced systems that encouraged learning through the use of reflection and other learning activities. The institutions in this study follow institution-wide policy-enshrined practice and operate from centralized offices that have both dedicated RPL staff and linkages across the institution. Institutions represented in this study support portfolio learning, which results in the production of rigorous portfolio compilations that exhibit and document learners’ claims of prior learning as described earlier in this paper.

Institutions represented in this study also reflected a number of different delivery formats. Two institutions are open and distance institutions, plying their RPL practice entirely at a distance; several institutions operate over a distributed network of campuses, often embracing substantial geographical distances; only two institutions employ an entirely face-to-face delivery mode. While a comparative element was not included in the study, that is comparing ODL data with face-to-face data, it became obvious that there was no difference in the scope and nature of participants’ responses as regards the challenge of language and their use of language. In light of current educational trends toward widening access and reducing barriers to learning worldwide and of the recent celebration of open educational resources (OERs) as a future support for and contributor to post secondary learning, these findings are encouraging and positive and should help to ease both ODL and traditional institutions toward RPL consideration.

The study comprised several data-gathering stages. Initial questionnaires containing open and closed questions were distributed to identified respondents. These data provided background information and established participants’ broad perceptions of their experiences with the RPL process and placed them within the normal demographic of RPL learners – generally middle-aged working adults who are engaged in part-time postsecondary study. Specifically, questionnaires asked learners about their understanding of knowledge-building activities in their respective systems. RPL practitioners responded to similar but adapted questionnaires. Ethical protocols were strictly observed.

Following the initial data collection, followup interviews and focus groups were conducted with selected participants who had indicated a willingness to engage further. Additionally, many participants engaged as a first step with the primary researcher in one-on-one interviews and focus groups of various sizes, conducted both face-to-face and by teleconference.3

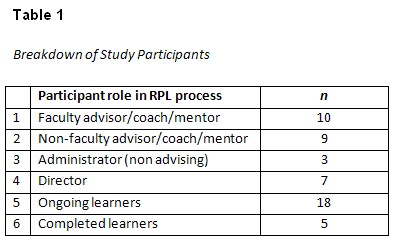

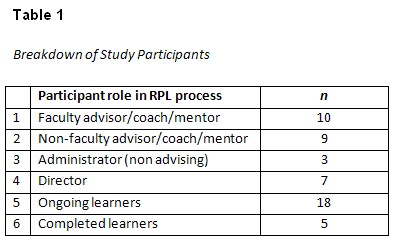

Table 1, below, details the breakdown of participants.

In the qualitative tradition, questions were used as starting-points and participants were able to explore the meanings of questions with the researcher (Creswell, 2003). From the subsequent compilation of data and analysis of participants’ experiences with RPL, researchers codified, categorized, and thematized data (Creswell, 2003). The study was limited by the following conditions pertaining to RPL: only portfolio learning was under study (not prior learning by challenge exam, for example); learners who had withdrawn from an RPL process were not surveyed.

Within the broad spectrum of university recognizing prior learning processes, the systems in question have adopted various combinations of rigorous, intensive, text-based processes and oral interviews. Practitioners’ descriptions of RPL processes as portfolio learning generally reflect embedded emphases on cognition and knowledge-building. Portfolio learning itself is described as a

rigorous, systematic and comprehensive process of identifying, articulating, and documenting one’s own learning, including the skills and knowledge acquired through experiential means (in the workplace, community, and in the family) as well as through structured and formal education and training. (Personal correspondence with D. Myers, 2007)

Portfolio learning is acknowledged to contribute to many positive and desirable outcomes, among them increased self-knowledge, greater appreciation of informal learning, improved communication and organization skills, and greater appreciation of the role of reflection (Brown, 2003).

Portfolio learning comprises two types of learning. At the first and most obvious level, learners are called upon to bring forth their prior and experiential learning and present it to assessors in structures and at levels that are acceptable to the institution. In itself, the backward-looking and self-reflective engagement that is necessary for these processes to occur is cognitively rewarding but arduous (Conrad & Wardrop, 2010; Peters, 2006). Research has shown that learners engaged in this process benefit from a sustained connection with a coach or a mentor (Conrad & Wardrop, 2010).

The opportunity for a second type of learning is created when learners build on the actions of surfacing and articulating university-level and relevant knowledge: in this way, learners are able to reflect on and gain insight into their own learning process, both processually and historically. The longitudinal aspect of examining one’s own knowledge acquisition over many years combined with the in-depth aspect of deep and sustained self-reflection can, theoretically, bring learners face-to-face with an enhanced understanding of their own ability to respond to information, ingest it, and create from the intersection of those actions a new sense of personal awareness. It is a heady process for learners – at the same time empowering and frightening. In one learner’s words,

[RPL] was a great experience! I learned so much about myself. It was really empowering to realize how much experience and knowledge I had gained throughout my work and life. ….It worked out very well for me; it has been an amazing and life-changing experience. …It is a lot of hard work, but definitely worth it, and the results are so rewarding!

Freire (1970) popularized the term banking for educational processes that positioned learners as empty, or at least receptive, vessels, in which teachers deposited information to a desired state of “fullness” and then expected learners to repeat that knowledge back to them. Freire rejected this stance and moved educators toward Bakhtin’s (1981) theory of dialogic teaching which places teachers and learners and the knowledge they exchange in a relationship of co-teaching and co-learning, “cultivating the development of an authentic community of learners, characterized by sharing and support, along with cognitive challenge” (Vella, 2000).

In the same vein, Vygotsky (1978) drew a distinction between learning by patterning and learning by puzzling. Patterning, where we learn by comparing to and building on similar experiences, has been the more traditional process in Western educational systems. Puzzling, where new situations give learners no reference point, does not depend on reaching back to existing generalizations and, as such, requires more social support than learning by patterning. Portfolio learning that asks learners to construct shape and form from their prior experiential learning draws on the puzzling methodology rather than patterning. Or, as Pokorny (2009) suggests,” any [RPL] process which aims to recognize and value learning from different contexts would have to engage with the heterogeneity of the knowledge distribution process rather than seeking familiarity.”

Given the complexities of portfolio learning tasks, it is not surprising that language figures prominently and critically into the learner’s process. Fluency and adeptness in language use, always important in university study, takes on even greater importance in systems where the learner’s presentation to assessors is dependent upon a written document without the possibility of an oral interview.4

A discussion of the importance of language and writing within portfolio learning – the topic of this paper – must be framed within the broader discussion of students’ writing and language use within academic programs of study. Lillis (2001) highlighted “the centrality of writer identity in student writing” (p. 33) by drawing on the work of Bakhtin (1981), who described the complexity of the student voice – “the utterance” – as being “entangled, shot through with shared thoughts, points of view, alien value judgments and access” (p. 276). Bakhtin’s work on utterance and the related concept of addressivity (1986) challenged the notion of language-as-conduit. In this view, which is analogous to the interactive engagement of constructivism as opposed to the positivist transmission model of learning (Pratt, 1998), utterances are alive and fluid; words are understood to create meaning rather than simply convey meaning (Lillis, 2001). Lillis also cites Clark, in Clark and Ivanic (1997), in posing three questions that underpin and inform student writing: “Who can you be [while writing]”? What can you say? And, ultimately, “How can you say it?” Portfolio learners are likewise subject to the breadth of these language concerns.

This discussion proposes that there are three areas of language and writing importance in portfolio learning, and that they occur somewhat sequentially. Initially, learners enter the RPL process, generally, by engaging in some sort of initial advising process with personnel who are trained in this area. The term advisor is used by some institutions; seemingly clear, this term contains a certain amount of ambiguity as it serves, in some institutions, to describe subsequent mentoring or coaching functions as well as initial set-up-oriented, direction-finding functions. Secondly, learners spend time – sometimes the majority of their time – working closely on mastering the articulation and expression of their prior learning. Good language skills, specifically the ability to nuance closely-related terms, are critical to this part of portfolio preparation. Lastly, arising and resulting from the engagement that learners experience with their own learning and with mentors who coach them in understanding their learning dynamics, learners appear to often be able to grow into thinking metaphorically about themselves as learners and, in so doing, develop some fluency in the language of metaphor. This final and third type of language skill is not always sequential in that it may develop together with other language skills over time; often, though, because of the level of difficulty or oddity associated with metaphorical thinking and speaking, this skill comes – if it does – near the end of the portfolio learning process. A more detailed description of these language roles follows.

Research indicates that language is one of the largest issues for learners during portfolio preparation (Conrad & Wardrop, 2010; Pokorny, 2006). The importance of language manifests as soon as learners begin their process. Because learners encounter different types of help from RPL personnel with varying job titles and functions, this discussion addresses three ways in which RPL learners engage with or confront language issues.

On a very technical level, learners must first learn the language of RPL as it distinguishes from other administrative university languages, for example the language of transfer credit. The “high-level stakes” (Barrett & Carney, 2005) importance of the learning determines the base-level need for learners to be exact and precise when referring to university processes, emphasizing the fact that there are many diverse processes that will affect or contribute to their success within the institution. Understanding the complexity of university processes and taking care to reflect those processes in accurate language should mark the beginning learners’ journeys into an academic world that, while set in its ways, holds the promise of open doors. An easy lesson? Perhaps, but still potentially daunting. Those in early contact with new portfolio learners report high levels of anxiety and stupefaction among them as they experience this first learning curve. Learners require and appreciate patience, care, and support at this stage.

This lesson, related to the first, thrusts learners into the knowledge that there is a realm of “university-speak” that is different from what exists outside the academy. This is not an isolated RPL lesson; in fact, it is an extension of the larger, elevated-language plane that hallmarks university life, rightly or wrongly. Learners are often quite taken aback by this knowledge; mastering the curve of university-speak throws them into initial shock (Conrad & Wardrop, 2010). Several processes must occur in tandem with each other as learners move into and through this stage of language-adaptation. They must come to know that the university use of and emphasis on certain words is not affectation, that in fact the nuanced distinction that separates comprehending, for example, from applying is indeed indicative of a different kind of knowledge function.

This is the most influential and difficult of the trio of initial lessons, the “high-level” lesson that should ultimately set the foundation for portfolio learners to bridge from their past understandings of doing something, or performing in a stipulated manner, to creating new territory, as in Vygotsky’s puzzling methodology. Through exposure to and acceptance of the academic lexicon and development of the skills to work within that language, learners become able to think of their own achievements within the new and expanded framework of learned experience. That is, learners begin to see that knowing how to write the report that they produced actually entails many other definable levels of knowledge acquisition and that they indeed have that knowledge. What may have begun, for learners, with a statement that denoted “I wrote a report” will end in their ability to describe myriad activities and steps contained within the report-writing function and to understand the knowledge-base that underpins those actions. For example, some of those steps may include researching and setting the parameters of the report, ascertaining readership or audience for the report, sketching out an outline that follows the cognitive development of the report, and so forth.

Learners’ initial introduction to RPL’s language vagaries and complexities opens the door to a second level of critical language use which helps learners understand how to articulate their learning. Several RPL processes under study relied on Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy as a foundational structure for this work. (Bloom’s work was updated in 2001. Krathwohl and Anderson’s elaborations are acknowledged while the original taxonomy is still respected.) While Bloom’s work does not necessarily provide the only basis for work in this area, it does accommodate RPL satisfactorily and worked well within several processes as the primary tool.

Bloom’s taxonomy distinguishes between six levels of “knowingness.” From most basic to most advanced, Bloom describes his categories as knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Krathwohl and Anderson’s (2001) revision essentially supplanted evaluation with creativity.

The distinctions between various levels of knowing represent a second arena of insightful – and generally novel – thinking for learners, the first being the critical separation of “knowing” from “doing,” as prescribed by RPL standards. In assisting RPL learners, mentors/coaches approach this distinction as the first step on the road to helping learners carefully deconstruct their prior learning. This is often a difficult hurdle for learners, as they are confronted, often for the first time, with surfacing the tacit knowledge that underpins their explicit ability to perform tasks or produce deliverables. Working through this process involved repeated asking of learners, “How? Why? In what way? To what effect? For what reason? The often-painstaking process, termed externalization by Nonaka (1994), has been described by mentors as “yanking and pulling” (Conrad, 2010) and represents a cornerstone in Vygotsky’s (1978) puzzling methodology, whereby learners learn by exception and surprise, rather than by rote patterning.

Once learners have clearly separated the fact of their “doing” from the store of knowledge that they have accumulated from having “done” something (for instance, having delivered a series of training workshops), their language skills are put to the test as they move forward into the process of determining the levels of each type of learning achievement. Do they simply describe how to deliver a stand-up workshop presentation? Can they analyze the tasks and steps buried within complex pre-development and development processes? Can they evaluate the relative worth of the session, of its outcomes, and of its component evolving processes?

The intricate cognition involved in thinking about the fine differences between knowing and doing, and between the various levels of knowing, requires learners to perceive of themselves as proactive agents – as “doers” rather than receivers; to perceive of themselves as owners and managers of the academic language within which they are asked to work; and to negotiate with a vocabulary that permits both actions to successfully occur.

Learners report on the sense of power they experience in coming to this level of comfort with language. The steps involved in this learning, not always sequential or hierarchical, are many and varied and can be quite seemingly small, for instance, introducing learners to active rather than passive voice construction. Helping learners to understand the nuanced differences in describing their participation in a team effort can serve as a large contributing factor to the building of self-esteem and to their appreciation of themselves as vital organizational stalwarts. As an example, “assessed team needs” and “provided planning and direction to team activities” speak of larger and more leadership-oriented team roles than do “assisted team members with product development” or “attended weekly team meetings.” With mentoring and coaching, learners are helped to grow into a process where they are able to discern that their “team assistance” was in fact a planning process that instigated the team’s moving forward.

As with any learning, the RPL process involves circularity, repetition, and movement from the known to the unknown. Generally, from initial levels of unfamiliarity with RPL, learners become acquainted with the idea of RPL through acquisition of new language tools and new vocabulary; with the process of RPL through an expansion of cognitive skills that is accompanied by new language; and with expressions of themselves as active agents, again accompanied by a new dexterity with the language. These types of proficiency with language permit learners to carefully and articulately demonstrate, in writing, their understanding of their own learning process. A type of labeling process results; “that’s what I have been doing all these years” is how one learner described her process of coming to that knowledge and finding the language for it. In one of the systems under discussion, this kind of scrupulous written detailing of prior experiential learning was essential as there is no opportunity for a personal interview or for direct exchange with those who are conducting the assessment of the learning portfolio.

Beyond the functionality of the portfolio, as discussed above, and its rewarding high-stakes outcome in the form of awarded credit toward a university credential, learners’ acquired language use can potentially move them forward into a new sphere of self-understanding that approaches the level of metaphor. In adult education-based or -oriented courses, it is not unusual for learners to either study the use of metaphors or to stumble across writing or resources that use metaphor in their argument. Intense RPL engagement opens similar avenues for learners’ exploration of new ways to envision themselves as learners, professionals, and individuals. “I am a voyageur,” declared a learner. “I am a bridge, spanning past to future,” said another, having found the language to denote both his growth and his work within his organization.” In his work on RPL and metaphor, Starr-Glass (2002) alluded to the strength of “seeing the relationship between the candidate’s experience and the academic norm” (p. 228) while cautioning that “exact replicas” of candidates’ learning will not be located in the academic world.

University study, overall, is fraught with issues of power, authority, and control (Foucault, 1979; Peters, 2006). Reflecting this long-established academic concern, accordingly, recent trends in university education – for example distance education, online learning, and the new worlds of social-networked learning and virtual learning environments (VLEs) – have also opened up discussions around the distribution of power and control (Dron, 2007; Garrison, 2000; Poster, 1996). Learners seeking assessment within RPL processes are equally susceptible to and affected by power dynamics inherent in culture, identity, and language concepts (Harris, 2000; Peters, 2006; Pokorny, 2009). At the root of the issue is the intrinsic difficulty of epistemology, the study of knowledge, and the tendency of higher education institutions to protect and exalt the parameters of that study. From the learners’ perspective, they were sensitive to the need to learn the “ways of the institution,” to learn “how to write academic,” the initial results of which included learners’ self-chastising feelings of “I am not good enough,” “I am out of my depth,” and “I am uneducated.”

New research has shed light on assessors’ perspectives of RPL processes. In their study on the language of assessment, Travers and colleagues (2011) determined the presence of cultural dynamics at every turn. As learners struggle to find and assert their voices and find language that they hope will be appropriate and acceptable to university culture, assessors – usually well entrenched in university culture – are making judgments in a variety of voices, using a range of language that is dependent upon each assessor’s particular stance (Travers et al, 2011). Some assessors simply assert their power, “depend[ing] on an authoritative voice as justification for stating that the learning occurred” (Travers et al, 2011). “For example, comments such as, “it is my belief that she already possesses an expert knowledge” and “I believe [she] deserves to gain credit for her … learning experience” use an authoritative voice,” but the authors point out that, in the interests of good assessment, more explanation and justification is usually provided in order to substantiate the assessment decision.

Assessors’ language is also determined by the culture of their area of study or the culture of their field (Travers et al, 2011). In the same way, learners’ language is dependent upon their culture or the culture of their background areas of interest, but learners’ language is not privileged by a “power stance” in the way that assessors’ language is. For example, learners with a strong computing or science background will write in strong, technical language as befits their training, while assessors’ measures of evaluation of that writing are grounded in university-level, academic and critical thinking rather than in attention to scientific detail.

Learners often speak of the transformative power of RPL engagement. Through the processes of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action (Schön, 1987), learners uncover new and deeper meaning in both their past achievements and their current undertakings. New ways of thinking unfold in front of them; their interior lives become richer places in which to dwell. The “increased self knowledge” outcome, documented in research (Brown, 2003; Conrad & Wardrop, 2010) translates further into a new sense of self-discovery and increased empowerment. Have these RPL learners been transformed?

Mezirow (1990) differentiated reflective learning from transformation, defining reflective learning as involving “assessment or reassessment of assumptions” (p. 6). Of transformative learning, defined as “when assumptions or premises are found to be distorting, inauthentic, or otherwise invalid” (p. 6), he stated:

Transformative learning results in new or transformed meaning schemes, or, when reflection focuses on premises, transformed meaning perspectives. To the extent that adult education strives to foster reflective learning, its goal becomes one of either confirmation or transformation of ways of interpreting experience. (1990, p. 6)

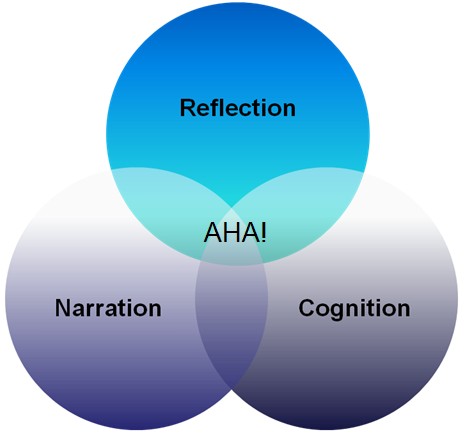

The Venn diagram (below, Figure 1) captures the writer’s view of the tripartite learning process inherent in institutional portfolio learning, as described in this study. Does the “aha” intersection contain transformative learning? It’s possible: learners speak anecdotally of RPL learning as life-changing, as did the learner who described it as “an amazing and life-changing experience.” Similarly, learner Darlene declared that “the self-reflection I have had to engage in during this long and often difficult PLAR assignment has been very helpful to me,” and Karen reiterated that her “portfolio, detailing my entire learning history, has again afforded an opportunity for self-reflection, self-acknowledgement and a sense of accomplishment.”

Figure 1. Venn diagram of the tripartite learning process inherent in institutional portfolio learning.

Whittaker, Whittaker, and Cleary (2006) suggest that, to facilitate transformation, learners “should be encouraged to perceive themselves as taking control of their own learning, which is both empowering and motivating, rather than as simply responding to the demands of academic validation, which, though necessary, is highly de-motivating” (p. 314). Both this suggestion and Whittaker et al.’s (2006) further suggestions of biographical writing and mentorship are all good ones and represent practices followed by the institutions in this study. Whatever the process of transitioning to new abilities, new knowledge, or new identities, or whatever the level of transformation achieved, access to new language is clearly essential to facilitate the journey.

Not all RPL portfolio learners need to – or will – achieve the levels of fluency of thought and language described here in order to succeed in the prior learning process. The earning of university-level credit through RPL may be achieved successfully without noticeable growth and insight, or transformation. Practitioners are generally confident, however, that all learners will have gained value to some level. Similarly, not all learners will term the RPL portfolio experience “the best time of my life” as one learner did. But many will echo this learner’s concluding assessment: “Completing the [RPL] portfolio challenged me to the level that I could ‘feel’ new pathways opening in my brain! It was terrific and terrifying at the same time!” It seems apparent that some of those “new pathways” opening in this learner’s brain resulted from the exploration and expansion of learners and their language, a critically important step in the portfolio process.

It is clear from this limited look at language use in portfolio learning within a smallish study that there is room for a great deal of further research in this area. The discussions contained herein broach on several well-established theoretical areas of investigation around issues of language and origin of language within speakers, identity and the relationship of identity to language, learning cultures, effective academic writing across all institutional study, cognition, and philosophical approaches to learning, specifically transformative learning. The twin notions of power and politics within institutional learning, alone, underpinned by echoes of Freire and Foucault, could drown smaller discussions regarding learners’ performance. Respecting the understanding that research is built on the “shoulders of giants,” the writer is grateful to Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) for the opportunity to contemplate some of these questions and acknowledges the vast terrain open to future research in these areas of study.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl,D. R. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Response to a question from the Novyi Mir editorial staff. In C. Emerson & M. Holquist (Eds.) (translated by V. W. McGee), “Speech genres” and other late essays (pp. 1-9). Austin, TX: University of Texas.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. Austin: University of Texas.

Barrett, H., & Carney, J. (2005). Conflicting paradigms and competing purposes in electronic portfolio development. Retrieved from http://www.taskstream.com/reflect/whitepaper.pdf

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook 1: The cognitive domain. New York: David McKay.

Brown, J. O. (2003). Know thyself: The impact of portfolio development on adult learning. Adult Education Quarterly, 52(3), 228–245.

Clark, R., & Ivanic, R. (1997). The politics of writing. London: Routledge.

Conrad, D. (2010). Through a looking glass, astutely: Authentic and accountable assessment within PLA practice. Adult Higher Education Alliance (AHEA) Proceedings. Saratoga Springs, NY: Empire State College.

Conrad, D., & Wardrop, E. (2010). Exploring the contribution of mentoring to knowledge-building in RPL practice. Canadian Journal for Studies in Adult Education, 23(1), 1–22.

Creswell, J.W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dron, J. (2007). Control and constraint in e-learning: Choosing when to choose. Hershey, PA: Idea Group.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Garrison, D. R. (2000). Theoretical challenges for distance education in the 21st century: A shift from structural to transactional issues. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 1(1).

Harris, J. (2000). RPL: Power, pedagogy and possibility. Pretoria, SA: Human Sciences Research Council.

Ivanic, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lillis, T. M. (2001). Student writing: Access, regulation, desire. London: Routledge.

Mezirow, J., & Associates. (1990). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organizational Science, 5(1), 14-37.

Poster, M. (1996). Databases as discourse, or, electronic interpellations. In D. Lyon & E. Zureik (Eds.), Computers, surveillance, and privacy (pp. 175–192). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Peters, H. (2006). Using critical discourse analysis to illuminate power. In P. Andersson & J. Harris, (Eds.), Re-theorising the recognition of prior learning (pp. 163–182). Leicester, UK: NIACE.

Pokorny, H. (2009). Some reflection on APEL/PLAR practice in England (PowerPoint presentation). Kamloops: International Centre for PLAR Research.

Pratt, D. (1998). Five perspectives on teaching in adult and higher education. Melbourne, FL: Krieger.

Schön, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Starr-Glass, D. (2002). Metaphor and totem: Exploring and evaluating prior experiential learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 2(3), 221–231.

Travers, N., Smith, B., Ellis, L., Brady, T., Feldman, L.,Hakim, K., Bhuwan, O, Panayotou, M., Seamans, L., & Treadwell, A. (2011). Language of evaluation: How PLA evaluators write about student learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning (IRRODL), 12(1), 80–95. Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/946

Vella, J. (2000). A spirited epistemology: Honoring the adult learning as subject. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 85, 7–16.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Whittaker, S., Whittaker, R., & Cleary, P. (2006). Understanding the transformative dimension of RPL. In P. Andersson & J. Harris, (Eds.), Re-theorising the recognition of prior learning (pp. 301-319). Leicester, UK: NIACE.

1The writer uses the more-universal term RPL, Recognition of Prior Learning, instead of the Canadian PLAR.

2Data cited were, and are being, gathered for a SSHRC-funded research project.

3Timing and geographical location created occasions whereby the researcher interviewed or conducted focus groups with willing participants who had not completed the initial questionnaire. In these cases, a detailed description of the research question and intent was provided to participants by the researcher. Questions for discussion were extrapolated from the preliminary analysis of questionnaire responses.

4There are many reasons, often pedagogical, for not including an oral interview as a part of RPL assessment processes. The logistics of distance is only one reason.