Alexander McAuley and Fiona Walton

University of Prince Edward Island, Canada

Offered between 2006 and 2009 and graduating 21 Inuit candidates, the Nunavut Master of Education program was a collaborative effort made to address the erosion of Inuit leadership in the K-12 school system after the creation of Nunavut, Canada’s newest territory, in 1999. Delivered to a large extent in short, intensive, face-to-face courses, the program also made extensive use of online supports. This paper outlines the design challenges – geographical, technological, pedagogical, and cultural – that faced the development and delivery of the online portion of the program. It highlights the intersection of the design decisions with the decolonizing principles that framed the program as a whole, the various and varying roles played by the online environment over the course of the program, and the program’s contribution to student success.

Keywords: Inuit; Aboriginal; distance graduate program; decolonization; pedagogy; K-12; school administrator; Indigenous education; Nunavut; decolonizing; educational leadership; distance education; distance learning; blended learning; knowledge building

Nunavut, created in 1999, translates to our land in English. As its name suggests, the territory was the culmination of nearly three decades of lobbying and negotiation by the Inuit of northernmost Canada for recognition of their rights to the lands they had occupied for centuries. As well as being the most significant change to the map of Canada in 50 years, the process of creating Nunavut made the Inuit the largest group of private landowners in the world and established a de facto Aboriginal government by virtue of the territory’s 85% Inuit demographic.

While satisfying the legal and political requirements for an Inuit homeland, the creation of Nunavut was problematic with respect to establishing such things as the new government and economic self-sufficiency. In terms of the education system, the challenges of establishing the new territory resulted in a significant reduction in the number of Inuit educators in schools as many moved to jobs in the new bureaucracy. Advances in local control were also undermined because the divisional boards of education were eliminated. The net result of these events was fewer Inuit educators in schools, especially in leadership positions, which caused feelings of isolation and disempowerment to develop among Inuit who remained in the education system (O’Donoghue et al., 2005).

A survey of all educators in the Nunavut regions during the mid-1990s identified the need for graduate studies to be offered in Nunavut for Inuit (Nunavut Boards of Education, 1995; O’Donoghue, 1998). A 2004 study (O’Donoghue et al., 2005) reaffirmed this finding and set in motion a chain of events that resulted in the creation of the Nunavut Master of Education (MEd) program, initially offered between 2006 and 2009 (Tompkins, McAuley, & Walton, 2009). The program was based on highly successful MEd outreach programs developed by the University of Prince Edward Island (UPEI) for small communities in northern Alberta. Unlike its Alberta counterparts, however, the Nunavut MEd made significant use of an online component. The remainder of this paper will situate the online component within the MEd program, explore the pragmatic and theoretical reasons for its inclusion and design, and summarize its contribution to the program as a whole. The authors will conclude the paper with lessons learned and plans for the program to continue to be offered through 2010–2013.

From a geographic perspective, Nunavut seems like a natural candidate for distance learning programs. Its 30,000 residents live in 28 communities with populations ranging in number from 140 to 6,200 scattered across the northeastern portion of Canada’s landmass. The territory constitutes one-fifth of the entire country, nearly 2 million square kilometers. There are no roads between communities or between Nunavut and southern Canada, and except for snowmobile trails and a brief shipping season from August to October, only transportation by air is available. Bringing people together is expensive at the best of times and is often impossible because of extreme weather conditions. Even so, all communities have satellite access to TV, radio, and the Internet.

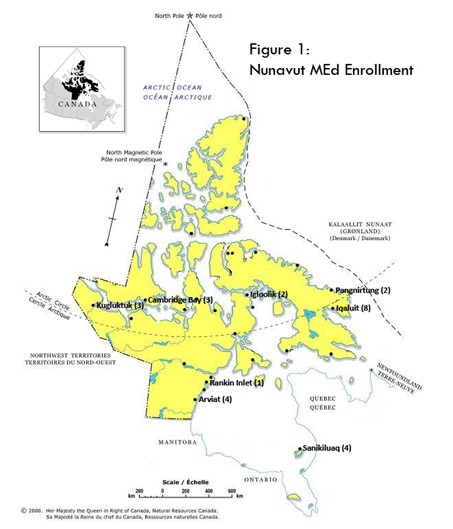

The 27 candidates in the program came from eight of these communities – Igloolik, Iqaluit, Pangnirtung, Sanikiluaq, Kugluktuk, Cambridge Bay, Arviat, and Rankin Inlet (Figure 1). All were Inuit women with bachelor of education degrees who held leadership positions in education and their communities and who spoke Inuktitut or Inuinnaqtun as their mother tongue. While some were graduates of the northern high school system, several were survivors of the residential schooling model, a colonial legacy that existed into the 1980s. The candidates were therefore representative of 85% of the Inuit population of Nunavut and, more particularly, of the 50% of Inuit who still identify Inuktitut as their home language.

The restriction of the Nunavut MEd to Inuit candidates was regarded as a controversial policy at first, incurring charges of racism from some quarters. It was, however, based on the fact that Inuit educators and the linguistic and cultural capital they bring with them are severely underrepresented in the school system, particularly in leadership positions. Moreover, compared to non-Inuit educators, Inuit are more likely to find that family and community obligations make it difficult for them to take graduate programs at universities in the south. A graduate program offered to Inuit in Nunavut therefore fit within the stated goals of the Government of Nunavut for a public service that reflects the territory’s demographics and is shaped by Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit or traditional Inuit values.

Although geography and logistics argued for the potential of distance learning as a delivery mode for the MEd in Nunavut, other factors urged caution. As mentioned above, while Inuit educators in Nunavut had expressed an interest in starting an MEd program by distance education, they were only one-sixth as likely to wish to take courses or workshops by distance education as their non-Inuit peers (Nunavut Boards of Education, 1995, p. 6) and over twice as likely to “find it hard to take a distance education course” (p. 14). The choice of the typical ten-course, part-time outreach MEd program from UPEI partially addressed this issue with its emphasis on short, intensive, face-to-face courses. It did, however, require further adaptation to the Nunavut context. Most salient for this paper, given the distribution of the program candidates, a fully face-to-face program would have been prohibitively expensive and would have required unacceptably long absences from candidates’ home communities. A blended program combining face-to-face meetings and distance learning was therefore necessary. How the blending would take place was the next issue.

Whether face-to-face or at a distance, the program had to respond to a number of fundamental concerns. All candidates were Inuit and spoke Inuit Uqausingit (Inuit languages) as their mother tongue and believed strongly in the importance of Inuit language and culture in the MEd program in particular and the school system in general. At the same time, many expressed the fear that the program might become “watered down,” an accusation also leveled by a number of the program’s critics. Because there were no Inuit with advanced degrees in education at the time, the decision was made to hire lead instructors with extensive experience in the North and to draw on the participation of Elders and guest speakers as adjunct instructors. A related decision was to encourage the use of written and spoken Inuit Uqausingit in courses wherever possible.

At a deeper level in terms of both program content and design, designers of the Nunavut MEd program intended to acknowledge and create a critical focus on the postcolonial context in which it existed. To what extent do the values and methods for creating and validating knowledge in a conventional academic program intersect, conflict with, or dominate those at the heart of Inuit society? To what extent and how could the MEd program provide access to the academic and economic capital of a graduate degree while questioning and reframing the underlying assumptions? As an initial step toward addressing this concern, an instructor with extensive northern Canadian experience and a background in cultural grief counselling became an integral member of the program team and a part of virtually every course. In addition, content that drew from Indigenous experience in the North and elsewhere was used extensively. Finally, several courses integrated presentations by Elders, and two of these individuals, Mariano Aupilardjuk and Meeka Arnakaq, received honorary degrees from the University of PEI at the end of the program (Tompkins, McAuley, & Walton, 2009).

Smith’s “Indigenous Research Agenda” (1999, p. 117), with its emphasis on decolonizing, mobilization, and transformation through four “tides” (survival, recovery, development, and self-determination), provided an initial conceptual framework that situated the overall goals of the Nunavut MEd within the larger sociocultural, -political, -epistemological, and -ontological contexts. Reflected in various forms of writing explored by students throughout the program, her “Twenty-five Indigenous Projects” helped make explicit the connection between their individual and collective work and the wider project of decolonization.

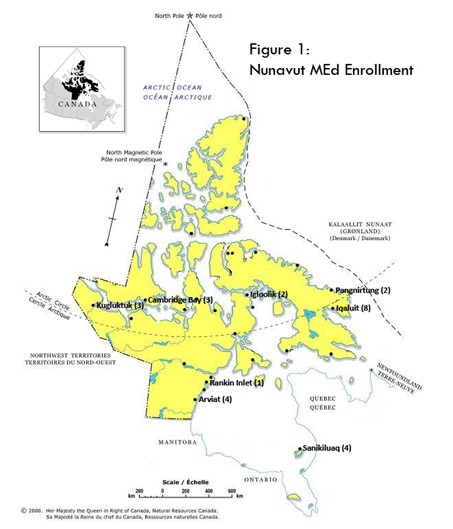

A second, perhaps more diffuse conceptual framework permeating the Nunavut MEd, was that of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ). A framework that “embraces all aspects of traditional Inuit culture including values, world-view, language, social organization, knowledge, life skills, perceptions and expectations” (Government of Nunavut, 2005, p. 5), Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit is being used to guide the development of all government initiatives in Nunavut, including education. The diffuseness of this framework with respect to the Nunavut MEd is a result of its being an emergent “work in progress,” particularly at its intersection with the values and structures of contemporary governmental institutions and practices.

As Figure 2 illustrates, six of the eight Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit principles are relational, that is, they focus on connections between individuals and their sociocultural, psychosocial, and physical environments. Although all eight principles influenced the design of the distance learning portion of the MEd, relationality was particularly important.

Based on this discussion, the ideal distance learning environment for the Nunavut MEd would support enduring relationships between widely distributed students and instructors over the three-year program, bridging both geographic separation and the gaps between courses. As well as supporting program delivery, the goal was to create a sense of the persistence of the course content and student–student, instructor–student, and instructor–instructor relationships. Asynchronous text-based interaction in Inuit Uqausingit and English was the minimum necessary requirement; however, a synchronous audiovisual mode would have enhanced the sense of presence between participants and extended it to the participation of Inuit Elders and their knowledge, which is primarily oral. A final goal was to make the environment lend itself to student control, that is, not dependent solely on instructional or institutional impetus for use.

The explosion of multimodal web-based technologies over the past 10 years should have made possible all of these affordances. Two limiting factors intervened, however, the first being the erratic nature of broadband Internet connections within Nunavut and the second the desire for a consistent and coherent means of online support. Although all Nunavut communities have broadband Internet access and the quality of that access has improved since it first became available in the mid-1990s, it still lags far behind what is available in most of southern Canada in terms of both bandwidth and reliability. Experiments with iVocalize, Elluminate, and Skype quickly demonstrated that Internet-based synchronous audio and audio-video multipoint interaction were a greater source of frustration than facilitation as participants inevitably dropped offline unexpectedly, had difficulty connecting, or experienced garbled transmissions. Non-Internet teleconferencing alternatives might have been possible, but were generally much more expensive, less flexible, and less open to student-initiated ad hoc use. Synchronous multipoint interaction was therefore reduced to scheduled teleconference calls, and even these were handicapped by having to coordinate four time zones. Yet despite its shortcomings, Skype did find a very useful role for casual, point-to-point contact because its contact list readily displayed the online status of program participants.

Although the results of experiments with synchronous multimedia environments were disappointing, they had been anticipated, and the decision to rest most of the distance learning component of the program on an asynchronous web-based system was made well before the program began. Abundant alternatives meet these criteria, ranging from open source learning management systems (LMS) such as Moodle and Sakai to commercial products such as Blackboard and Desire2Learn. Because its use had been intrinsic to a longitudinal study of network-supported knowledge building in the Northwest Territories/Nunavut and because that research had documented a knowledge building framework relevant to and effective within the cross-cultural northern context (McAuley, 1998; McAuley, 2001; McAuley, 2004; McAuley, 2009), a knowledge building environment (KBE) called Knowledge Forum became the underlying technology for the program. While Knowledge Forum had superficial similarities to other environments in terms of its support for such things as nested discussions, uploaded documents, inline display of a variety of multimedia formats, and links to external web-based resources, conceptually and in terms of some critical technological affordances it was very different.

The Knowledge Forum environment implemented to support the Nunavut MEd was built around three organizing principles: community, agency, and ideas (McAuley, 2004). Candidates in the program were expected to contribute to a community that worked with ideas in order to create new knowledge. Participation in this community required that candidates take active roles (agency) both in the processes of working with the ideas (contributing, questioning, critiquing, synthesizing, and so on) and in shaping the social processes by which the community worked (supporting each other, dividing labor, being open, and sharing resources). Agency was also critical for participants to integrate the emerging IQ principles into the online environment. Given that the principles are as much “a living technology . . . a means of organizing family and society into coherent wholes” (Arnakak, 2001) as they are a fixed set of traditional values, allowing the non-Inuit lead instructors to predefine their roles in the online environment would have been inappropriate at best. Consistent with Scardamalia and Bereiter’s work on the principles underlying effective knowledge building communities and the technical and social affordances of knowledge building environments to support them (Scardamalia, 2002), and Cummins’ work on effective intervention for collaborative empowerment in bilingual contexts (Cummins, 2001, 1996), the community/agency/ideas framework provided a starting point from which to begin exploring a distance learning environment consistent with both Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and the Nunavut MEd as a decolonizing project.

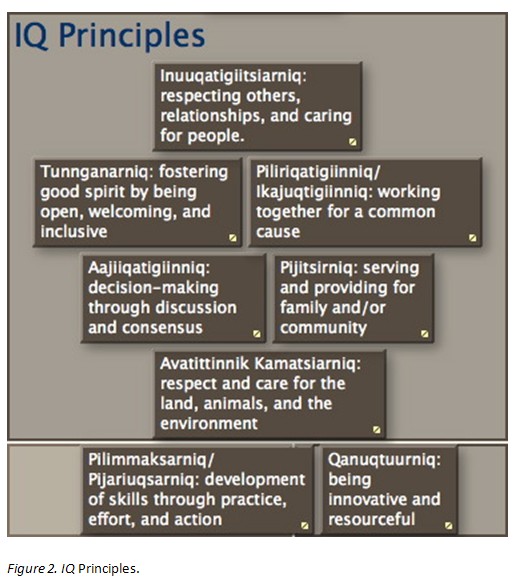

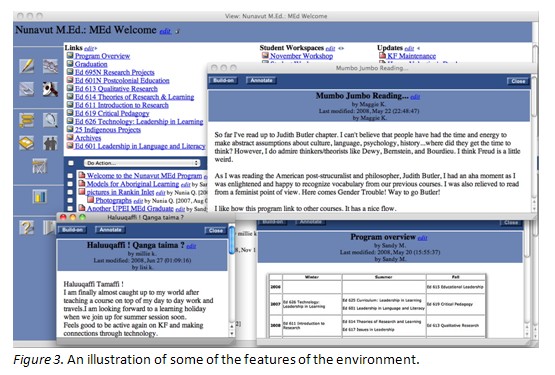

Password protected and accessible via a Web browser (a more sophisticated Java-based interface exists, but might not have survived problematic Nunavut Internet connections), the Nunavut MEd Knowledge Forum environment created a single envelope for all online aspects of the program. Instructors defined the initial organizing structures for each course and students followed these structures for their initial contributions, but the fluidity of the environment allowed emergent structures as well. So, for example, if a participant wished to pursue an idea or question later in the program, she could search the entire corpus of the Knowledge Forum database for relevant contributions, create a new view, and continue to work with the material, all without leaving the environment. Regardless of when it was made, each contribution to the Knowledge Forum persisted throughout the full length of the program as a potential resource. The knowledge embodied in the Knowledge Forum was not static, but continually open to review, reassessment, and revision. In the spirit of an open community, all contributions were visible and open to comments and annotations by all participants.

The image in Figure 3 shows the opening view of the Nunavut MEd database and three notes, one of which is partly in Inuinnaqtun and another which contains a graphic. A view, which might be considered analogous to a topic, is an online space to which contributions in the form of notes can be posted to form threaded discussions. Notes can contain text, graphics, multimedia objects, and file attachments such as PDFs. The upper space of the view has been designed with a header that provides ready access to critical notes and commonly used hyperlinks to other views. Participants can respond to notes with “annotations” (electronic post-it notes) inserted into a note or “build-ons” external to the note that are indented to form the “thread” of the discussion. The left-hand portion of the view provides access to tools that allow participants to create notes, views, and links, attach documents and multimedia objects, and search across the database using a number of criteria. Additional tools such as keywords, problem fields, discourse scaffolds, and automatic referencing facilitate participants to move beyond simply contributing to a discussion to work with the knowledge that emerges from them.

The notion of actually working with the notes contributed to the online discussions and is probably the defining feature of Knowledge Forum, distinguishing it from most other online environments. All participants, instructors, and students alike can create new views and move notes into those views from others to emphasize new or emerging understandings. They can edit and revise their notes in response to annotations or to reflect deeper understanding. This kind of “knowledge work” was probably best shown in student portfolio views, in which students drew together notes from across several views to demonstrate their learning or in pre-course assignments which asked them to reframe work from previous courses in preparation for engaging new concepts or material.

While Knowledge Forum served as the foundation for the online support of the Nunavut MEd, Skype and low-bandwidth multimedia presentations created using Impatica for PowerPoint supplemented it in the courses offered solely at a distance. As indicated previously, Skype allowed participants and instructors to see who was online at any given time and thus encouraged communication and relationship building without incurring large costs or the time wasted playing “telephone tag.” PowerPoint presentations could be created by instructors without sophisticated digital production skills and were used to support learners working in their second language and to supplement mainstream academic texts with relevant northern examples. Participants used them as user-friendly audiovisual introductions to their academic English-language texts. Figure 4 shows the first slide of one such presentation. Based on a Nunavut MEd research quilt, developed by course candidates during a fall workshop, it contextualized the first week’s work in the online course beginning the following January.

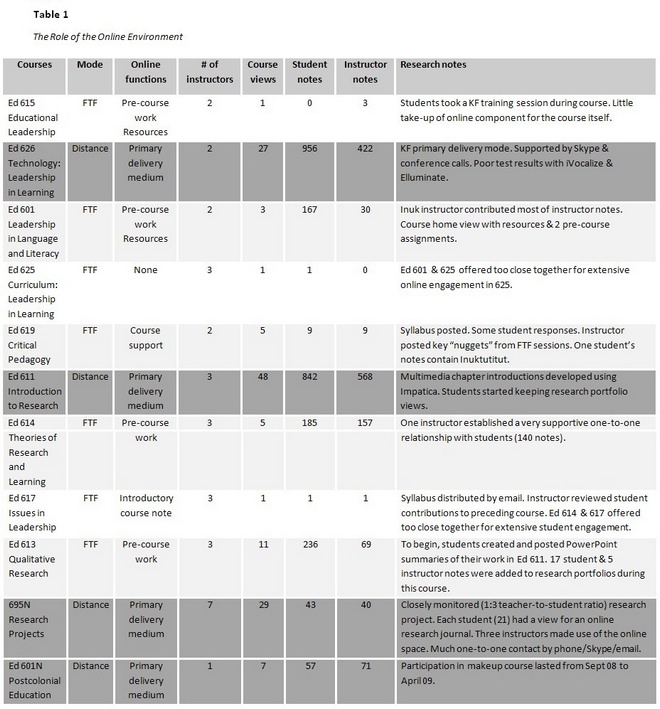

The following table summarizes the role of the online environment across the 10 regular courses and one makeup course of the Nunavut MEd. White rows indicate courses in which the online environment played little or no role, while light grey rows indicate those in which it played some role, and dark grey rows indicate courses offered completely via distance learning. A larger number in the course views column indicates greater complexity in the use of the online environment than a smaller number. The numbers of student and instructor notes provide a rough measure of the extent of online engagement. The research notes column highlights additional details about each course.

As Table 1 shows, the online environment played the main role in four of the eleven courses, a lesser role in four more, and no significant role in the remaining three. No online expectation had been set up for the first course of the program, during which a training session for using the program was held. The lack of a significant role for the online environment in the other two courses was partially the result of their being the second course in two-course, back-to-back summer offerings and partially the result of an instructor’s lack of comfort with the environment.

Informal feedback, anonymous course evaluations, and feedback from structured interviews painted an almost universally positive picture of the contribution of the online component to the Nunavut MEd. Described as a “big plus” by one MEd candidate and “our lifeline” by another, its overall importance was probably best summarized in the words of a third:

Knowledge Forum allows for interaction that couldn’t take place otherwise. Collaboration can take place across Nunavut. When we are forced to use technology we learn new ways to feel part of a community in such a large territory. Sometimes being forced to do something launches you into it. (Telephone interview)

Access to other students and instructors that would have otherwise been impossible was a recurring theme in much of the feedback and speaks to the creation of a community that spanned the vast distances, geographic and otherwise, that separated candidates and instructors. Another student speaks to this on a more conceptual level, noting that, “What worked was we learned to share our views online openly” (Ed 626 Student Evaluation). Given the complicated interpersonal relationships that sometimes played out in both the small communities and the face-to-face sessions, the confidence to share openly is very significant. This is not to say that the online engagement was without challenges. As another student’s comment demonstrates, sometimes the complexities of life in a small community made working online difficult: “It was my first time to do [an] online course. It was difficult to concentrate on my work because I work at home most of the time” (Walton, McAuley, Tompkins, Fortes, & Frenette, 2008).

Whether using the online environment as the primary delivery medium or as a supplement to face-to-face sessions and regardless of their previous experience with online or distance learning, the majority of instructors were very positive about Knowledge Forum. One instructor’s comment echoes the students’ opinion about the role of Knowledge Forum then goes on to extend it to one of the program goals, enhancing student writing skills: “Knowledge Forum has provided a valuable support in facilitating communication and provides a site for the development of writing skills. It needs to be maintained and used in all courses whenever possible.” The instructor elaborates, “This means that instructors not familiar with Knowledge Forum and how to use it must be told of this expectation and given support to implement it” (Walton et al., 2008, p. 30).

This comment reflects a certain initial ambivalence toward the online environment in the program as a whole. Although there were debates about the specific platform and whether a synchronous audiovisual capability was a “need” or a “want,” the necessity of an online environment in the distance learning courses was never questioned. Given the skepticism about distance learning expressed by Inuit educators in the Pauqatigiit survey (Nunavut Boards of Education, 1995), the reluctance to adopt a top-down mandate that would push instructors into unfamiliar territory, and the uncertainty of whether adequate assistance could be put into place to support them fully if they ventured there, the possibility that online engagement would supplement the intensive face-to-face courses was for the most part left to chance. It took the cumulative experience of the entire three-year program to develop and demonstrate a coherent, integral role for the online component.

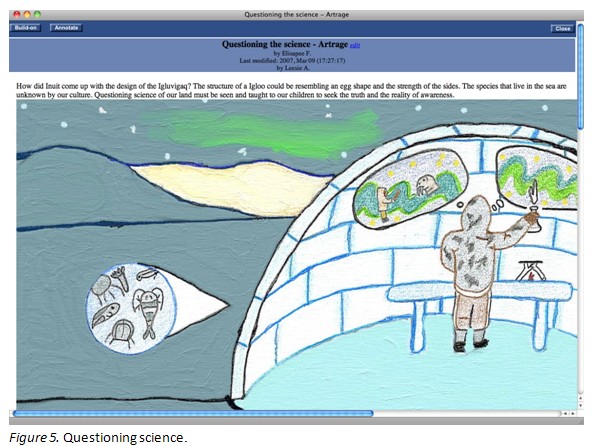

With its juxtaposition of a graphic created by an MEd candidate using a natural media computer-based drawing program called ArtRage (which was free at that time) and a text-based reflection on the intersection of Inuit and Qallunaat ways of knowing, Figure 5 encapsulates the potential of the Knowledge Forum environment as a medium to support the processes of decolonization and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit integral to the Nunavut MEd.

The Knowledge Forum environment that was constructed for the program and, more importantly, that evolved over its course provided a consistent interface, a set of tools to facilitate working with knowledge contributed by both instructors and students and the flexibility to respond to emerging priorities. By supporting a single interface for all Nunavut MEd courses and providing the means to seamlessly search for, identify, and move contributions from one course to any other, the program helped to create a community with social and learning dimensions that extended across Nunavut and between the courses. As well as the course material preserved there, the online space provided a persistent, living record of many of the challenges that the candidates faced over the three years.

Although any number of other technologies might have supported similar processes to some extent, as Mott and Wiley (2009) point out, most LMSs embody a banking model of education (Freire, 1970, 2000). While straightforward and efficient, a system based on this model would have reinforced the colonial framework the Nunavut MEd was intended to problematize. The knowledge building principles and the sociotechnological affordances of Knowledge Forum based on them (Scardamalia, 2002) facilitated an approach to online support for the Nunavut MEd that explicitly acknowledged and responded to the underlying principles of the overall program, specifically the colonial history of Nunavut, its detrimental influence on Inuit education, and the effort to move beyond these through critical foci on decolonizing practices and the relational principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. Although its implementation was tentative and somewhat inconsistent over the three years of the program, this approach contributed to the success of an environment that encouraged one student to say in an interview, “We learned as much from each other through KF as we did from our instructors.”

While both students and instructors recommended that the second iteration of the Nunavut MEd retain the Knowledge Forum online environment when it launches in the fall of 2010, a number of changes are planned to build on the lessons learned over the last three years. Perhaps most significantly, all courses will be planned with a significant online component regardless of whether the primary delivery mode is face-to-face or at a distance. Instructors will be offered regular and consistent support to that end, both formally from the program’s distance learning coordinator and informally from the experiences of past instructors returning to the program, which include a number of Inuit graduates from the previous cohort. The challenge remains, of course, to maintain and strengthen the emphasis on the underlying principles of the program while supporting an emergent online environment that responds both to instructional requirements and the sociocultural learning goals of candidates.

A final challenge remains for the longer term. Although the Nunavut MEd Knowledge Forum environment has remained open at the request of students since the program ended, no participation has taken place since shortly after the graduation ceremony in July 2009. Apparently having done its job, it has fallen silent and the knowledge created by program candidates remains inaccessible. Given the groundbreaking work completed by several candidates in their efforts to understand the colonial forces that have shaped education in Nunavut and to contribute to its decolonization, this is a major loss. To avoid similar losses in the future, an easy-to-use bridge between the walled garden of Knowledge Forum and more open and accessible web-based media must be developed.

Arnakak, J. (2001). What is Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit? Retrieved from http://www.turtletrack.org/Issues01/Co01132001/CO_01132001_Inuit.htm

Cummins, J. (1996/2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society. Los Angeles, CA: California Association for Bilingual Education.

Freire, P. (1970/2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: The Seabury Press.

Government of Nunavut, Curriculum and School Services. (2005). Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit education framework. Iqaluit, NU: Author.

McAuley, A. (1998). Virtual teaching on the tundra. Technos, 7(3), 11–14.

McAuley, A. (2001). Creating a community of learners: Computer support in the eastern Arctic. Education Canada, 40(4), 8–11.

McAuley, A. (2004). Illiniqatigiit: Implementing a knowledge building environment in the eastern Arctic (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Toronto, ON: OISE/University of Toronto.

McAuley, A. (2009) Knowedge building in an Aboriginal context. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 35(1). Retrieved from http://www.cjlt.ca/index.php/cjlt/article/view/514/244

Mott, J., & Wiley, D. (2009). Open for learning: The CMS and the open learning network. In Education, 15(2). Retrieved from http://www.ineducation.ca/article/open-learning-cms-and-open-learning-network

Nunavut Boards of Education (1995). Pauqatigiit: Professional needs of Nunavut educators. Iqaluit, NU: Author.

O’Donoghue, F. (1998). The hunger for professional learning in Nunavut schools (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Toronto, ON: OISE/University of Toronto.

O’Donoghhue, F., Tompkins, J., McAuley, A., Hainnu, J., Fortes, E., Metuq, L., & Qanatsiaq, N. (2005). Decolonizing Inuit education in the Qikitani region of Nunavut from 1980–1999. Ottawa, ON: Social Science and Humanities Research Council.

Scardamalia, M. (2002). Collective cognitive responsibility for the advancement of knowledge. In B. Smith (Ed.), Liberal education in a knowledge society (pp. 67–96). Chicago, IL: Open Court.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies. London, UK: Zed Books.

Tompkins, J., McAuley, A., & Walton, F. (2009). Protecting the embers to light the qulliit of Inuit learning in Nunavut communities. Inuit Studies, 33(1–2), 95–113.

Walton, F., McAuley, A., Tompkins, J., Metuq, L., Qanatsiaq, N., & Fortes, E. (2005). Pursuing a dream: Inuit education in the Qikiqtani region of Nunavut from 1980–1999 (Research report submitted to the Department of Education, Government of Nunavut). University of Prince Edward Island, Faculty of Education: Authors.