Volume 22, Number 2

Phil Tietjen1 and Tutaleni I. Asino2

1Davidson-Davie Community College, 2Oklahoma State University

Open pedagogy has been touted by advocates as a promising expansion of open educational resources because it involves shifting from making resources accessible to impacting the practice of teaching. The allure of the term coupled with its promise to bring greater innovation to pedagogy has led to its widespread use at conferences and publications. However, as the concept has gained increasing levels of popularity, it has also sparked considerable debate as to what it means. For example, how is open pedagogy distinct from other forms of pedagogy such as critical or cultural? What does it mean to practice open pedagogy? Without a clear understanding of its meaning, establishing a solid research foundation on which to make claims about the impact of open pedagogy approaches is difficult. Accordingly, this article argues that the current debate signals the need for the development of robust analytical frameworks in order to construct a cohesive body of research that can be used to advance it as a field of study. To do this, the authors review the literature and identify common characteristics within it. The authors then propose a five-part framework that encourages the long-term sustainability of open pedagogy.

Keywords: open educational resources, open pedagogy, open educational practices, framework

The field of open education has been steadily growing since the Cape Town Declaration of 2002. Research has included issues pertaining to adoption of open educational resources (OER) and evaluation and impact at the student, faculty, and institutional levels (Braddlee & VanScoy, 2019; Colvard et al., 2018). Griffiths et al.’s (2020) recent study examining the impact of Achieving the Dream’s OER degree initiative shows an explosion of OER courses, particularly on community college campuses. As OER has gained momentum, some of its ardent supporters have argued that it should consist of more than free books or resources. They state that it offers compelling implications for pedagogy, such as increasing the level of student engagement and pedagogical innovation (Andrade et al., 2011; Orr et al., 2015). Advocates for this view often use the general umbrella term: open pedagogy (OP) (DeRosa & Robison, 2017; Hegarty, 2015; Wiley, 2013). But for those who are interested in practicing OP, what exactly does that mean? What processes, steps, and/or benefits does that entail? How do they make it happen? More broadly, what exactly does it mean to practice or do OP?

On the surface, OP seems attractive, as the term itself evokes a very optimistic and uplifting imagery of teachers openly sharing ideas related to teaching and partnering with students in the education process. However, a review of the literature quickly reveals that there is no agreed-upon definition of what the term OP means; indeed, quite a broad spectrum of proposed definitions exists. Some argue that OP is distinguished by the use of open licenses that enable learning materials to be freely accessed, reused, and remixed (Wiley, 2013). Others assert that it is less about resources and more about pedagogical practices where, for example, students become participants in a broader ecosystem of public knowledge (DeRosa & Robison, 2017; Luke, 2017; Morgan, 2016). As a complement to pedagogical practice, others advocate that it should be strongly connected to matters of social justice (Bali, 2016; Koseoglu, 2017). While the term OP has generated popular appeal, Jhangiani cautions that such popularity can also undermine its meaningfulness: “I am concerned about using the term ‘open’ so broadly and in so many ways that it becomes essentially meaningless” (Open Education Consortium, 2017, “What is Open Pedagogy?”, para. 4). Similarly, Hilton (2017) argues that the need for greater clarity and coherence is central to making research-based claims about the impact of OP:

Open pedagogy is frequently touted at conferences, yet little research has been done on its efficacy, how teachers/students perceive it, and so forth. ... Will widespread adoption of open pedagogy spark dramatic improvements in learning? Those who study this question need to carefully consider what they mean by open pedagogy, an increasingly contested term [emphasis added], and the metrics they use when determining whether open pedagogy leads to increased learning outcomes. (p. iv)

Hilton’s critique underscores the point that to make claims about the efficacy of OP and thereby establish a sustainable foundation of research, it is essential that we bring clarity and cohesion to how we conceptualize OP. With this in mind, we argue that it is time to bring a greater sense of cohesion to the concept of OP by identifying commonalities. Our purpose in this article is twofold: (a) to make sense of the OP concept as it has been discussed in the literature, and (b) to identify commonalities that can be used for building a flexible, responsive framework.

Before proceeding further, two important clarifications need to be made. First, part of the confusion around the definition of OP may be due to ambiguous use of terms. In our research, we often found this ambiguity to manifest itself in one of two ways: either (a) the term OP was used interchangeably with the term open educational practices, or (b) OP was presented as another branch of open education. Our primary interest centers on the adjective that links them both: open. Accordingly, since the purpose of this article is to make sense of this debate, our discussion and analysis will incorporate research that has used the terms OP and/or open educational practices (OEP).

The second clarification pertains to the history of the term OP. Morgan (2016), Jordan (2017), Rolfe (2016), and others have pointed out that the term OP has been around since at least the 1970s. While we recognize that the term is not new, for the purposes of this essay, we are focusing on the debate that has resurfaced since the introduction of social Web technologies as tools for expanding the impact of open education (Brown & Adler, 2008) and especially since the publication of the 2011 Open Educational Quality Initiative (OPAL) report (Andrade et al., 2011), which called for OER to impact pedagogical practice as well as provide access. With this in mind, our discussion pertains to research that has occurred within the general time frame of the 2010s to the present.

In reviewing the literature, we focused on sources that specifically address the challenge of developing a definition or conceptualization of OP. In addition, because we found that the term OP was often used interchangeably with the term open education, we included that term as well.

We used a university library database that simultaneously searches major databases (e.g., EBSCO, PsycINFO). As inclusion criteria, we included the following source types: articles, book chapters, conference proceedings, and books published between 2011 and 2020. We employed Boolean search parameters to ensure that only materials that contained the exact words were returned. This process yielded a total of 938 articles (Table 1).

Table 1

Search Results—Articles

| Term | Source type | No. articles found |

| Open education | Articles, book chapters, conference proceedings, and books | 273 |

| Open education | Peer-reviewed articles only | 181 |

| Open pedagogy (title only) | Articles, book chapters, conference proceedings, and books | 10 |

| Open pedagogy (any field) | Articles, book chapters, conference proceedings, and books | 95 |

| Open pedagogy (any field) | Peer-reviewed articles only | 63 |

| Open educational practices (any field) | Articles, book chapters, conference proceedings, and books | 272 |

| Open educational practices (title only) | Articles, book chapters, conference proceedings, and books | 44 |

| Total articles found | 938 | |

In reviewing of these results, we found that many were duplicate entries; eliminating those narrowed the results to 127 citations. We further analyzed these and found that 87 discussed the issue of definition in more than superficial detail (i.e., more than 1-2 sentences). Similarly, 24 of those 87 discussed it in substantive detail and were considered to have met the relevant criteria.

In addition to research databases, we also consulted blog posts from 2017 that were written by authors interested in OP. We chose to focus on blog posts from 2017 for three reasons. First, Open Education Global (formerly the Open Education Consortium) organized a yearlong celebration of various phenomena related to openness where the month of March was specifically dedicated to OP. Second, the Association for Learning Technology (ALT, 2017) dedicated the theme of its annual conference that year to issues pertinent to open education. Third, one of the more visible voices in OP, Maha Bali, compiled a list of blog posts from various educational technologists, teachers, and researchers who had used the ALT conference as material for writing their own thoughts concerning open education. Our review of this list found that 15 bloggers presented a definition of OP (Table 2).

Table 2

Blog Posts, 2017: Year of Open

| Author | Title | OP definition |

| Atenas | Open education in Palestine: A tool for liberation | No |

| Bell (1) | Preparing for OER17 | No |

| Bell (2) | Ground zero approaches to open #YearofOpen | No |

| Campbell | Open pedagogy—A view from a distance | No |

| Cangialosi | More questions than answers (about open ped) | Yes |

| Cronin (1) | OER17: Personal and political | No |

| Cronin (2) | Opening up open pedagogy | No |

| DeRosa | Open pedagogy: Quick reflection for #YearOfOpen | Yes |

| Fraser | Waves not ripples: Reflections on #OER17 | Yes |

| Groom | I don’t need permission to be open | Yes |

| Jhangiani | Definitions vs. foundational values | Yes |

| Kalir | Marginal syllabus as OER and OEP | Yes |

| Koseoglu | Open pedagogy: A response to David Wiley | Yes |

| LaLonde | Does open pedagogy require OER? | Yes |

| Luke | What’s open? Are OER necessary? | Yes |

| Morgan (1) | Open pedagogy and a very brief history of the concept | Yes |

| Morgan (2) | Reflections on #OER17—From beyond content to open pedagogy | Yes |

| Smith | Feature: Open is as open does | Yes |

| Veneruso | Convergence: Open pedagogy and complexity | Yes |

| Weller | My definition is this | Yes |

| Wiley | When opens collide | Yes |

*Note. OP = open pedagogy; OER = open educational resources; OEP = open educational practices.

In general, we found our first source of data (i.e., journal articles) provided more depth and detail, and so most of our discussion relies on that work.

We organize our findings into two phases: (a) phase 1, 2011-2016, where 2011 marks the publication of the 2011 OPAL report; and (b) phase 2, 2017 and beyond, which corresponds to the occurrence of two key events, namely, the Year of Open (2017), which compiled different definitions of OP, and the OER17 conference, which generated a considerable number of blog posts. In addition, we classified the definitions into two categories: (a) based on characteristics and (b) based on policy. Table 3 presents a sample of the definitions.

Table 3

Definitions of Open Pedagogy and Open Educational Practice

| Citation | Definition | Purpose |

| Bali et al. (2020) | Propose OEP definition based on a three-part typology ranging from (a) content-centric to process-centric, to (b) teacher-centric to learner-centric, to (c) pedagogical to primarily social justice focused | DBC |

| Bloom (2019) | OP refers to the broader practice of leveraging the permissions of open content to redesign educational experience to be more meaningful and engaging to students | DBC |

| Conole & De Cicco (2012) | Defines OEP on four dimensions: (a) strategies and policies, (b) barriers and success factors, (c) tools and tool practices, and (d) skills development and support | DBC |

| Cronin (2017) | OEP are collaborative and pedagogical practices that involve the creation, use, and reuse of OER as well as participatory technologies and social networks to interact, learn, create knowledge, and empower learners | DBC |

| Czerniewicz et al. (2017) | Views OP in terms of four aspects: (a) legal openness, (b) pedagogic openness and learning in networks, (c) encouraging others to teach and learn in open networks, and (d) reusing content in teaching and other contexts | DBC |

| Ehlers (2011) | OEP are defined as practices that support the (re)use and production of OER through institutional policies, promote innovative pedagogical models, and respect and empower learners as coproducers on their lifelong learning path (p. 4) | DBP |

| Franco et al. (2014) | OEP are practices that include the creation, use/reuse, and repurposing of OEP in order to innovate and improve education (OPAL, 2011a) | DBP |

| Hodgkinson-Williams (2014) | Defines OEP based on a proposed five-part framework regarding openness: (a) technical openness, (b) legal openness, (c) cultural openness, (d) pedagogical openness, and (e) financial openness | DBC |

| Koseoglu & Bozkurt (2018) | Defines OEP as “a broad range of practices that are informed by open education initiatives and movements and that embody the values and visions of openness” (p. 455) | DBP |

| Murphy (2013) | OEP refers to “policies and practices implemented by higher education institutions that support the development, use and management of OER, and the formal assessment and accreditation of informal learning undertaken using OERs” (p. 202) | DBP |

| Nascimbeni & Burgos (2016) | OEP are “practices ‘based on a competency-focused, constructivist paradigm of learning [that] promote a creative and collaborative engagement of learners with digital content, tools and services in the learning process’” (p. 1) | DBC |

| Paskevicius et al. (2018) | OP “focuses on the literacies and approaches to teaching and learning that take advantage of the unique affordances of OER” (p. 118) | DBC |

*Note. OEP = open educational practices; DBC = definition based on characteristics; OP = open pedagogy; DPB = definition based on policy.

A pivotal document in facilitating the shift from an emphasis on resources (i.e., OER) to pedagogical practice (e.g., OP, OEP) was the 2011 report by OPAL (Andrade et al., 2011). Ehlers (2011) builds on the OPAL report by proposing a framework that educational organizations can use to determine the degree to which they have shifted to practice. He defines OEP as “practices which support the (re)use and production of OER through institutional policies, promote innovative pedagogical models, and respect and empower learners as co-producers on their lifelong learning path” (p. 4). Nascimbeni and Burgos (2016) conceptualize OEP as a continuum on which the focus is more directly on the individual educator who may be unaware of OER and its implications for pedagogy. They argue that more attention needs to be given to the social change processes that inevitably need to happen if instructors are to adopt the identity of an open educator. Conole (2012) uses OEP as a way to emphasize the social processes that can facilitate a transition from resources to practice:

The vision of open educational practices includes a move from resource-based learning and outcome-based assessment to a learning process in which social processes, validation and reflection are at the heart of education, and learners become experts in judging, reflecting, innovating and navigating through domain knowledge. (p. 250)

Her definition highlights the liberatory dimensions of context as learners are no longer restricted to the boundaries of a proprietary textbook but are presented with pathways for participating in an open learning ecosystem. Hodgkinson-Williams (2014) proposes a framework that specifies five types of openness: technical, legal, cultural, pedagogical, and financial. She argues that successful implementation of OEP requires understanding different types of openness and how overcoming obstacles related to these different levels can vary depending on the geographic region of the world in which the implementation is being attempted. Schreurs et al. (2014) argue that the social learning dynamics that occur in contexts such as OEP are complex and involve shifting levels of membership and activity, therefore necessitating a different framework than more common, established social learning frameworks such as Communities of Practice. They propose conceptualizing OEPs as containing four “dimensions of social configuration”: practice, domain, collective identity, and organization (p. 5).

As noted previously, other scholars have used the term OP. One of the most visible conceptualizations of OP is Wiley’s (2013) 5Rs. First conceived in 2013, Wiley’s definition identifies five specific rights enabled by using an open licensing system:

One of the underlying forces driving Wiley’s conceptualization of OP is to combat the problem of the disposable assignment. In a traditional classroom, the student spends numerous hours working on an assignment that the professor then grades and returns; however, its purpose and usefulness generally end there. Wiley argues that the unfortunate consequence of this traditional academic transaction is that it treats the assignment as a disposable thing. He therefore proposes that students and teachers extend the value of this work by sharing it with the broader outside world. Such an emphasis connects to Scardamalia and Bereiter’s (2014) knowledge-building framework, which is well known in the learning sciences community: “In Knowledge Building theory, pedagogy and technology, students’ work is primarily valued for what it contributes to the community [emphasis added] and secondarily for what it reveals about individual students’ knowledge” (pp. 397-398). In Wiley’s 5Rs framework, having the right to freely distribute materials and therefore without the constraint of copyright is the key element that distinguishes OP from other forms of teaching practice.

From another perspective, Bali calls for greater semantic scrutiny of the word open: “When we call anything ‘open’ we need to clarify: What are we opening, how are we opening it, for whom, and why?” (Open Education Consortium, 2017, “What is Open Pedagogy Anyway?”, para. 1). These important framing questions extend the work of an earlier blog post titled “Reproducing Marginality?” (2016), where Bali looks at OP through a prism of power dynamics and questions that critically examine assumptions regarding how it manifests in practice. She argues that despite good intentions, open communities can still unwittingly create boundaries that marginalize certain voices; therefore, “opening doors is not enough,” since a genuinely open space requires that participants “listen and care and support marginal voices. Whether or not they wish to speak. Whether or not they wish to be present. Whether or not they like what we do” (Bali, 2016, para. 16).

In a similar vein, Bayne et al. (2015) argue that open is all too often viewed with an uncritical eye and framed in exclusively optimistic terms that downplay the different forms and levels of impacts created by implementations of openness: “Much less common is the acknowledgement that openness reconfigures or maintains particular notions of learning, teaching, and human being” (p. 248). They urge researchers and practitioners to view openness in a more nuanced way because without a more critical view, there is a tendency to oversimplify the organizational, political, economic, and other obstacles associated with pursuing educational models characterized as open. Another important contribution comes from Hegarty (2015), who conceptualizes OP as comprising eight attributes (e.g., participatory technologies, connected community). Central to Hegarty’s model is how OP enables individuals to share, modify, and repurpose learning materials with a broader community of learners and educators. Voices such as Hegarty’s represent an important first phase of contributions toward defining OP and OEP. Next, we turn to the second key phase of the definitional debate.

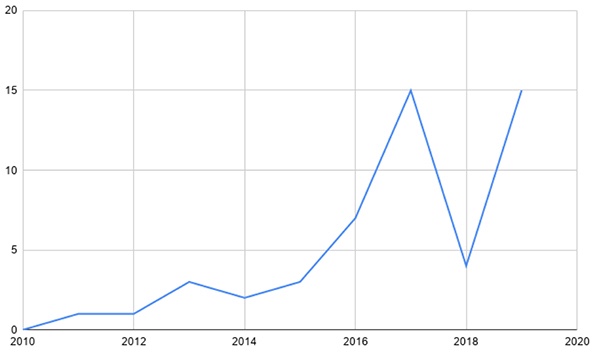

As noted, 2017 marked a significant moment in the various conversations and debates regarding how to define OP. First, there was a dramatic uptick in the number of articles published on the topic of OP (Figure 1). Second, 2017 was established as the Year of Open, with March dedicated to sharing different perspectives on OP. Third, the ALT organized its 2017 conference around discussing issues pertaining to open education, which in turn inspired many blog posts.

Figure 1

Research Articles on Open Pedagogy: Articles Using Open Pedagogy

Much of the literature on OP points to attributes such as open licenses and reusable assignments. For example, Jhangiani’s vision of OP centers on three key elements (Open Education Consortuim, 2017). The first is that open licenses are central to promoting the growth of innovative teaching and learning practices. Second, OP is primarily demonstrated through renewable course assignments. Third, OP actively encourages educators to openly share their course design and development practices. For DeRosa and Robison (2017), one of the most exciting benefits of OP is that students become active participants in knowledge-building communities that live beyond the immediate confines of their own classrooms.

Their conceptualization of OP draws inspiration from Stommel’s (2014) “critical digital pedagogy,” which, among other distinguishing practices, “centers its practice on community and collaboration” and its “application outside traditional institutions of education” (para. 3). Bloom (2019) explores OP within a community college setting and asserts that research studies of OP follow too limited a vision when they confine themselves to simple comparisons between learning contexts that use OER materials and those that do not. One of the distinctive advantages of OP is the way it uses the flexibility of open licenses to address the problem of disposable assignments, thereby enhancing the meaningfulness of the student’s learning experience. Nizami and Shambaugh (2019) see OP as a way to eliminate information barriers between universities and the broader community within which they are situated. They propose that OP should emphasize a holistic approach where open practices are not something that happen only within academic silos but include local community partners such as public libraries that can bring learning materials to marginalized constituents. Thus, social justice represents an important component of Nizami and Shambaugh’s vision of OP.

This second phase of 2017 also witnessed further conceptualizations of the related term OEP. Bali et al. (2020) present a three-dimensional framework that includes (a) content-centric to process-centric and (b) teacher-centric to learner-centric and (c) pedagogy-centric to social justice-centric (p. 2). They argue that successful OEP should actively support and encourage connections to a diverse range of voices. In addition, social justice represents a central component to their framework. They explain that projects such as Equity Unbound and the Open Pedagogy Notebook offer learners ways to channel the learning artifacts they create through OER as a means of ameliorating inequities that exist in the broader world.

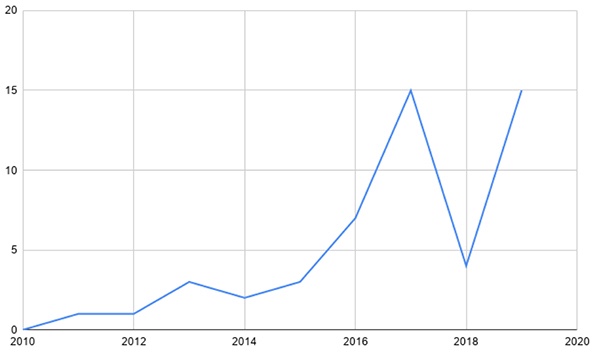

Cronin (2017) proposes a definition of OEP that considers instructors’ attitudes toward openness and how they shape their willingness to practice their teaching in more open ways: “collaborative practices that include the creation, use and reuse of OER, as well as pedagogical practices employing participatory technologies and social networks for interaction, peer learning, knowledge creation and empowerment of learners” (p. 18). Her definition is developed within the larger context of a study investigating the rationale and extent for why academic staff employ OEP. Cronin found that educators’ open practices could be expressed in terms of four dimensions: (a) balancing privacy and openness, (b) developing digital literacies, (d) valuing social learning, and (d) challenging traditional teaching role expectations (p. 23). Most prominent among these four dimensions was (a) balancing privacy and openness. Similarly, further data analysis suggests that the decision making related to this tension between privacy and openness could be expressed as four levels of consideration: macro, micro, meso, and nano (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Adaptation of Cronin’s Privacy and Openness Model

Adapted from “Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education.” By C. Cronin, 2017, The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). CC-BY.

This four-part consideration model underscores the need for greater awareness, connectedness, and recognition of the complexities of openness.

Karunanayaka and Naidu (2017) agree with many other OEP advocates who argue for the need to move beyond the accessibility of OER content and focus more on the way they can impact practice and cultivate creativity. But they extend that argument by asserting that the likelihood for success can be significantly enhanced by using a design-based research approach where OEP evangelists partner with those who are less familiar or enthusiastic. Doing this improves the chances for realizing a successful form of OEP that is more organic and compatible with the local context. Similarly, in a 2019 report for the European Union Joint Research Center, dos Santos and Punie see OEP as a way to shift the emphasis from availability of content (i.e., OER) to pedagogical practice. Echoing this emphasis on practice, Harrison and DeVries (2019) define OEP as including any, or all, of the following practices: creating or incorporating OER materials into learning contexts, using free and open-source software, and open sharing of research and scholarly practice. Koseoglu and Bozkurt (2018) propose that OEP should take an expansive approach, where interested educators and learners have multiple points of entry. These entry points can include practicing open scholarship, open assessments, and open teaching, as well as the creation, use, or adoption of OER materials. Paskevicius (2017) directs attention to how OEP can be aligned with specific phases of instructional practice (e.g., learning objectives, assessment).

A helpful complement to the work that appeared in journal articles was the array of contributions that appeared in educational blogs. Morgan (2017), for example, finds a lot to like in Wiley’s 5Rs but expresses reservations regarding its preoccupation with content: “Is content what defines open pedagogy?” (para. 5). Her vision of OP rests more on the practices and activities—that is, the means of how OP happens—than on the static content. For Cangialosi (2017), OP is about students and educators taking a more active role on the Web by claiming their own domains and digital identities. Practicing OP means making a political statement about individuals’ rights to establish and manage their own digital identities on the Web so they can use that freedom to create, customize, and contribute to learning experiences that are not bound by rules stipulated by commercial interests. Fraser (2017) is critical of the distinction between OP and open practice. She reasons that if OP is all about bringing educational and teaching practices out into the open, then why not use the word practice? She wonders if the word pedagogy is simply being used as “shorthand for educational practice” (para 5). Koseoglu (2017) resists seeing OP through a singular lens. With specific focus on Wiley’s 5Rs model, she asserts that the debate is less about definition than method. Luke (2017) asserts that Wiley’s 5Rs attach too much emphasis on resources, which is problematic because an undue emphasis on resources runs the risk of reducing pedagogy to a commodity or property. He argues that the distinguishing element of pedagogy is process and that this process plays out through traversing six dimensions of openness (e.g., isolation vs. connectedness), where each presents a tension between freedom and authority embedded in pedagogical processes. Overall, 2017 and beyond represents a period of significant volume of activity regarding the challenge of defining OP and OEP. Next, we identify some commonalities among this range of perspectives as a means toward building a framework for analyzing this phenomenon across contexts.

Perhaps aware of the considerable debate generated by the many attempts to define OP, Wiley and Hilton (2018) argue that the attempt to reach agreement on a “common definition” of OP is “essentially impossible” (p. 135). Accordingly, they propose that a more productive path is to avoid pursuing such a goal and instead propose a new term: OER-enabled pedagogy. The authors define OER-enabled pedagogy as a “set of teaching and learning practices that are only possible or practical in the context of the 5R permissions which are characteristic of OER” (p. 135). By moving away from the debate around the word open, they redirect the focus to the material artifacts of OER and the open licensing system that suggests its potential for bringing measurable impacts on teaching and learning. Their proposed new term tightens the link between OER and pedagogy. In this view, open is implicitly defined by the licenses because it is that which allows the artifact to move from something that is an academic classroom object to a community one.

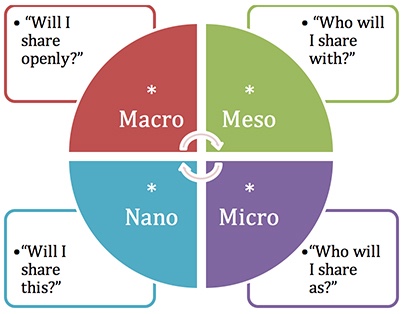

After reflecting on the work above, we conceptualize OP as comprising five elements.

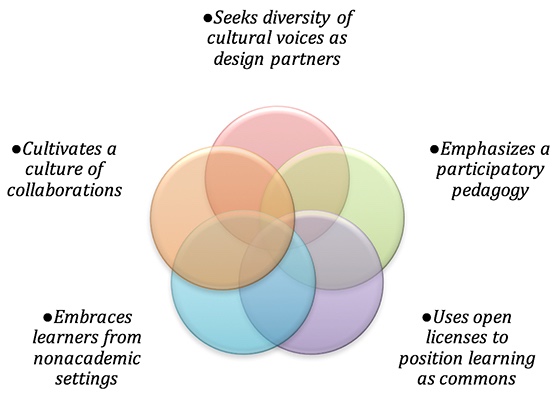

We graphically present these five elements with overlapping circles to emphasize interconnectedness and expand on each (Figure 3).

Figure 3

The Five-Circle Framework

First, we see OP as poly-vocal and thriving on a diverse spectrum of voices. As an Internet-enabled, knowledge-building collective, OP welcomes participation and contributions from around the globe. OP recognizes the vital role that international organizations such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE) have played in promoting the benefits and wider implementation of OP (e.g., OPAL Initiative, 2011). Efforts such as theirs establish the diversity of voices and representation as a distinguishing feature of OP.

Second, OP is a participatory pedagogy. Rather than seeing pedagogy in terms of a traditional instructor-student hierarchy, where the learner is the passive recipient of knowledge, it conceptualizes the learner as a peer contributor to a broader community that extends beyond the boundaries of a specific academic cohort. This is enabled through social Web technologies such as wikis, tagging, open messaging platforms, and similar tools.

Third, another important feature is the role of open licenses: without these, people cannot openly share, reuse, revise, and remix materials. This element draws its inspiration from open-source software and, more broadly, the notion of the commons, where a community openly shares and manages resources to respond to a particular need (Benkler, 2005; Ostrom, 1990). As an educational commons, the goal of students and teachers is to extend the value of their work by inviting the commons to build on it.

Fourth, OP also actively encourages participation from those outside traditional academic contexts. Educational research has long recognized the value of informal learning (Marsick & Watkins, 2001; Rogoff & Lave, 1984). Similarly, social Web technologies have dramatically enabled the growth of informal online learning communities (Greenhow et al., 2015; Thomas & Brown, 2011). OP builds on this existing precedent by welcoming and supporting the interests of learners whose style is more self-directed and not driven by academic credit.

Last, the opportunities to revise, remix, and openly share foster a culture of collaboration that enables opportunities for growth and innovation, especially as they relate to pedagogy, teaching, and learning practices. Practices in OP give wider exposure to a diversity of approaches, and as this diversity disperses outward across a wider network of learners and educators, it accelerates the pace of change and innovation in the field. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has required many faculty members to move their face-to-face classes to exclusively online contexts, but since many have had little experience with teaching online, they have been eager for ideas and resources related to online teaching. A community of OP practitioners can help educators better cope with crisis situations such as this.

As OER and OP mature as areas of educational practice, we believe it is important to make sense of these different perspectives and identify areas of commonality and divergence. In addition, given that OER and OP aim to reach a global audience, it is important to consider perspectives and related issues from researchers and practitioners around the world. One key takeaway from this exploration is that the concept of OP is difficult to reduce to a static, single-sentence definition. This is supported by the journal articles we reviewed, which show that researchers have chosen more often to focus on defining OEP instead of OP. One has to wonder if part of the problem is a refusal to question other fundamentals and ignore other questions, terms, or words that we have not yet settled, such as education or pedagogy.

The use of the word pedagogy is similar to that of education. The word education itself has gone largely overlooked in this debate. Its concept is often accepted at face value without asking what it is, what its purpose is, and whose education is being promoted. Brock-Utne (2002) has brought this question to bear in “Whose Education for All?” by suggesting that although “education for all” sounds nice, we must ask whose education is being promoted. Such an omission should not be overlooked as trivial or unnecessary. Latour (2005), for example, developed the analytical approach of Actor-Network Theory to, in part, call attention to how terms such as sociology become so firmly established in a disciplinary lexicon that they can obscure the debates and negotiations that lead to its firm position. He argues that especially when new developments or ideas emerge in a given field, it becomes important to reexamine or trace the contested lineage behind terms previously seen as immutable.

The conversation around the term pedagogy as it relates to the OP literature is also ominously mute. This is rather odd, given that the term pedagogy has been around for centuries. In the literature, it has often been contested, misread (Stommel, 2014), and at times blurred in translation (Hamilton, 2009); moreover, open is not the only modifier to append itself to the word pedagogy. Examples of others include cultural pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995), second language pedagogy (Prabhu, 1987), feminist pedagogy (Shrewsbury, 1987), pedagogy of the oppressed (Freire, 2018), and critical pedagogies (Darder et al., 2009), among many others. The focus on the modifier “open” is especially odd because what is important before debating a concept is to ensure a shared understanding of that very concept exists. In the literature, the term pedagogy is broadly explained as the art of teaching. However, as Alexander (2004) has aptly noted, “the spectrum of available definitions ranges from the societally broad to the procedurally narrow” (p. 9). Part of this variance is due to teaching being a practice that is contextually and culturally based; as such, if pedagogy is indeed the art of teaching, such a large spectrum of understanding of the term is to be expected. While the interrogation of the word pedagogy is beyond the scope of this article, we raise the omission to point out a rather massive gap in our literature. While we have had numerous debates on what open is, we have not done the same with the term pedagogy and what it specifically means within the context of the debate on the meaning of OP and related terms. This can mean either that we all share the same meaning and understanding of the concept or that we are engaged in a vigorous debate while having different meanings.

More broadly, the challenge that these definitional issues or questions raise is the need for a robust set of theoretical frameworks. Building theoretical perspectives enables us to think about how these different definitions can be linked to broader philosophical foundations and thereby conceptualize the phenomena of interest in more nuanced, richer ways. Indeed, this need for a set of robust theoretical frameworks is a challenge identified by Knox (2013).

Defining terms is an important aspect of any scholarly pursuits. Definitions help bound and guide conversations. They ensure agreement on the nature of a thing and provide a point of departure for discussions, debates, or agreement. Essentially, a definition acts as a calibrating lens to look at a phenomenon. In terms of the importance of a definition of OP, we agree with Wiley and Hilton (2018) that “the dearth of agreement on a common definition makes evaluating the impacts of open pedagogy on student learning, student engagement, and other metrics of interest essentially impossible since we cannot specify what we are evaluating” (p. 135). If OP advocates agree on and advocate for its value, as many of the authors described in our literature review certainly have, then it seems logical and appropriate to investigate its impact on teaching and learning. Doing this requires building a solid research foundation of theoretical frameworks and methods. Similarly, it also means that we, as a community, need to develop a coherent vocabulary so that as we build a corpus of research, there is a clear understanding of how specific terms, frameworks, and methods are being defined. We see this article as a step toward realizing that goal.

Alexander, R. (2004). Still no pedagogy? Principle, pragmatism and compliance in primary education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 34(1), 7-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764042000183106

Andrade, A., Ehlers, U.D., Caine, A., Carneiro, R., Conole, G., Kairamo, A.K., Koskinen, T., Kretschmer, T., Moe-Pryce, N., & Mundin, P. (2011). Beyond OER—Shifting focus to open educational practices: OPAL report 2011. Open Educational Quality Initiative (OPAL). https://www.oerknowledgecloud.org/archive/OPAL2011.pdf

Association for Learning Technology (ALT). (2017, April 5-6). OER17: The politics of open. Association for Learning Technology. https://oer17.oerconf.org/

Bali, M. (2016, September 4). Reproducing marginality? Reflecting Allowed. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://blog.mahabali.me/pedagogy/critical-pedagogy/reproducing-marginality/

Bali, M. (2017, April 21). Curation of posts on open pedagogy #YearOfOpen. Reflecting Allowed. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://blog.mahabali.me/whyopen/curation-of-posts-on-open-pedagogy-yearofopen/

Bali, M., Cronin, C., & Jhangiani, R. S. (2020). Framing open educational practices from a social justice perspective. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.565

Bayne, S., Knox, J., & Ross, J. (2015). Open education: The need for a critical approach. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(3), 247-250. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1065272

Benkler, Y. (2005). Common wisdom: Peer production of educational materials. Center for Open and Sustainable Learning. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/37077901/Common_Wisdom.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Bloom, M. (2019). Assessing the impact of “open pedagogy” on student skills mastery in first-year composition. Open Praxis, 11(4), 343-353. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.11.4.1025

Braddlee, D., & VanScoy, A. (2019). Bridging the chasm: Faculty support roles for academic librarians in the adoption of open educational resources. College & Research Libraries, 80(4), 426-449. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.4.426

Brock-Utne, B. (2002). Whose education for all? The recolonization of the African mind. Routledge.

Brown, J. S., & Adler, R. (2008, January 18). Minds on fire: Open education, the long tail, and learning 2.0. Educause Review. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2008/1/minds-on-fire-open-education-the-long-tail-and-learning-20

Cangialosi, K. (2017, April 23). More questions than answers (about open ped). Karen Cangialosi. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://karencang.net/open-education/more-questions-than-answers-about-open-ed/

Colvard, N. B., Watson, C. E., & Park, H. (2018). The impact of open educational resources on various student success metrics. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 30(2), 262-276. https://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/pdf/IJTLHE3386.pdf

Conole, G. (2012). Realising the vision of open educational resources. In Designing for learning in an open world (Vol. 4, pp. 245-264). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8517-0_13

Conole, G., & De Cicco, E. (2012). Making open educational practices a reality. Adults Learning, 23(3), 43-45.

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

Czerniewicz, L., Deacon, A., Glover, M., & Walji, S. (2017). MOOC—making and open educational practices. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29(1), 81-97

Darder, A., Baltodano, M., & Torres, R. D. (2009). The critical pedagogy reader (2nd ed.). Routledge.

DeRosa, R., & Robison, S. (2017). From OER to open pedagogy: Harnessing the power of open. In R. Jhangiani & R. Biwas-Diener (Eds.), From OER to open pedagogy: Harnessing the power of open (pp. 115-124). Ubiquity Press. https://doi.org/10.5334/bbc.i

dos Santos, A. I., & Punie, Y. (2019). Practical guidelines on open education for academics: Modernising higher education via open educational practices. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/55923

Ehlers, U.D. (2011). Extending the territory: From open educational resources to open educational practices. Journal of Open Flexible and Distance Learning, 15(2), 1-10. http://www.jofdl.nz/index.php/JOFDL/article/view/64

Fraser, J. (2017, April 20). Waves not ripples: Reflections on #OER17. Social Tech. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from http://www.josiefraser.com/2017/04/reflections-on-oer17/

Freire, P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed: 50th anniversary edition. Bloomsbury.

Greenhow, C., Gibbins, T., & Menzer, M. M. (2015). Re-thinking scientific literacy out-of-school: Arguing science issues in a niche Facebook application. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 593-604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.031

Griffiths, R., Mislevy, J., Wang, S., Shear, L., Ball, A., & Desrochers, D. (2020). OER at scale: The academic and economic outcomes of Achieving the Dream’s OER degree initiative. Achieving the Dream. https://www.achievingthedream.org/resource/17993/oer-at-scale-the-academic-and-economic-outcomes-of-achieving-the-dream-s-oer-degree-initiative

Hamilton, D. (2009). Blurred in translation: Reflections on pedagogy in public education. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 17(1), 5-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360902742829

Harrison, M., & DeVries, I. (2019). Open educational practices advocacy: The instructional designer experience. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology/La Revue Canadienne de l’apprentissage et de La Technologie, 45(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt27881

Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology, 55(4), 3-13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44430383

Hilton, J. (2017). Empirical outcomes of openness. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3378

Hodgkinson-Williams, C. (2014, June 25). Degrees of ease: Adoption of OER, open textbooks and MOOCs in the Global South. University of Cape Town. http://hdl.handle.net/11427/1188

Jordan, K. (2017, June 19). The history of open education—A timeline and bibliography. Shift+refresh. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://shiftandrefresh.wordpress.com/2017/06/19/the-history-of-open-education-a-timeline-and-bibliography/

Karunanayaka, S. P., & Naidu, S. (2017). A design-based approach to support and nurture open educational practices. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 12(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-01-2017-0010

Knox, J. (2013). Five critiques of the open educational resources movement. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(8), 821-832. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.774354

Koseoglu, S. (2017, April 21). Open pedagogy: A response to David Wiley. Completely Different Readings. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://differentreadings.com/2017/04/21/open-pedagogy-a-response-to-david-wiley/

Koseoglu, S., & Bozkurt, A. (2018). An exploratory literature review on open educational practices. Distance Education, 39(4), 441-461. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1520042

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00028312032003465

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford University Press.

Luke, J. (2017, April 23). What’s open? Are OER necessary? EconProph. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://econproph.com/2017/04/23/whats-open-are-oer-necessary/

Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. E. (2001). Informal and incidental learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 21(89), 25-34. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.5

Morgan, T. (2016, December 21). Open pedagogy and a very brief history of the concept. Explorations in the Ed Tech World. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://homonym.ca/uncategorized/open-pedagogy-and-a-very-brief-history-of-the-concept/

Morgan, T. (2017, April 13). Reflections on #OER17—From beyond content to open pedagogy. Explorations in the Ed Tech World. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://homonym.ca/uncategorized/reflections-on-oer17-from-beyond-content-to-open-pedagogy/

Nascimbeni, F., & Burgos, D. (2016). In search for the open educator: Proposal of a definition and a framework to increase openness adoption among university educators. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(6). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i6.2736

Nizami, U., & Shambaugh, A. (2019). Open pedagogy through community-directed, student-led partnerships: Establishing CURE (Community-University Research Exchange) at Temple University Libraries. Open Praxis, 11(4), 443-450. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.11.4.1028

OPAL. (2011). Beyond OER: Shifting focus to open educational practices (OPAL Report 2011). Open Education Quality Initiative.

Open Education Consortium. (2017, April). April open perspective: What is open pedagogy? Year of Open. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://www.yearofopen.org/april-open-perspective-what-is-open-pedagogy/

Orr, D., Rimini, M., & Damme, D. van. (2015). Open Educational Resources: A Catalyst for Innovation. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264247543-en

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Paskevicius, M. (2017). Conceptualizing open educational practices through the lens of constructive alignment. Open Praxis, 9(2), 125-140. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.9.2.519

Paskevicius, M., Veletsianos, G., & Kimmons, R. (2018). Content is king: An analysis of how the Twitter discourse surrounding open education unfolded from 2009 to 2016. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i1.3267

Prabhu, N. S. (1987). Second language pedagogy (Vol. 20). Oxford University Press.

Rogoff, B. E., & Lave, J. E. (1984). Everyday cognition: Its development in social context. Harvard University Press.

Rolfe, V. (2016, November 2). Open. But not for criticism? [Conference session]. #OpenEd16: The 13th Annual Open Education Conference, Richmond, VA. https://www.slideshare.net/viv_rolfe/opened16-conference-presentation

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2014). Knowledge building and knowledge creation. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 397-417). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139519526.025

Schreurs, B., Van den Beemt, A., Prinsen, F., Witthaus, G., Conole, G., & De Laat, M. (2014). An investigation into social learning activities by practitioners in open educational practices. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(4). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i4.1905

Shrewsbury, C. M. (1987). What is feminist pedagogy? Women’s Studies Quarterly, 15(3/4), 6-14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40003432

Stommel, J. (2014, November 17). Critical digital pedagogy: A definition. Hybrid Pedagogy. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://hybridpedagogy.org/critical-digital-pedagogy-definition/

Thomas, D., & Brown, J. S. (2011). A new culture of learning: Cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change (1st ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Wiley, D. (2013, October 21). What is open pedagogy? Improving Learning. Retrieved February 25, 2021, https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975

Wiley, D. (2014, March 5). The access compromise and the 5th R. Improving Learning. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/3221

Wiley, D., & Hilton, J. L., III. (2018). Defining OER-enabled pedagogy. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(4). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3601

What Is Open Pedagogy? Identifying Commonalities by Phil Tietjen and Tutaleni I. Asino is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.