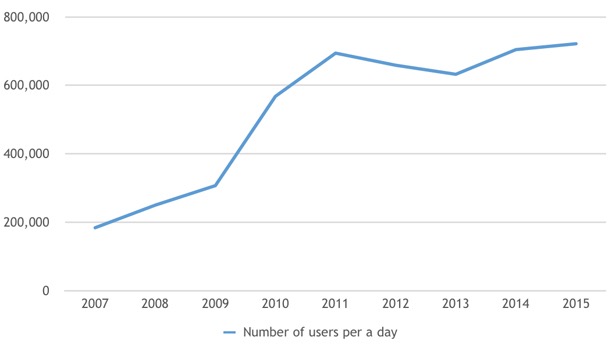

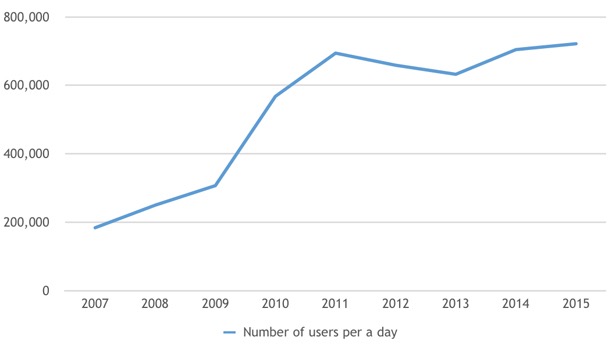

Figure 1. Number of EBS video lecture users, Ministry of Education South Korea (2016).

Volume 18, Number 4

SuBeom Kwak

The Ohio State University

Since 2005, open educational resources (OER) have played a key role in K-12 education in South Korea; so far, however, there has been little discussion about OER efficacy in South Korean K-12 education. In the meantime, South Korean education has been attracting a lot of interest around the world. Former U.S. President Obama's comments about South Korean education might also be caused by South Korean students' academic performance evaluated by international large-scale assessments such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). This article uses an ethnographic perspective to explore the experiences of teachers and students in the Korean context. The analysis of the findings shows how teachers adopt and adapt OER for their 12th grade (the final year of secondary school) Korean language arts classes. Through classroom observations, interviews, and questionnaires, this exploration revealed that nearly 92% of the students perceived OER as beneficial to their studies and that teachers were spurred on to orchestrate differentiated instructional plans by OER. We argue that there is significant value to using OER in the formal educational curriculum, but that a lack of knowledge of how to adapt OER restricts how their potential is realized in practice. We identify implications for maximizing OER adaptation and successful usage of OER in K-12 education.

Keywords: OER, open educational resources, EBS, Korean language arts, K-12

Since a UNESCO Forum on Open Courseware in 2002, many countries have seen the rapid development of OER. Open educational resources (OER) are important: OER are a way of addressing issues such as the rising cost of textbooks for students, they provide opportunities for teachers to customize materials, and overall can strengthen school education. With increasing potential, OER came to the surface to support the conventional educational system in many countries around the world (Butcher & Wilson-Strydom, 2008). In South Korea, as an approach to adapting OER into the practice of teaching in formal education, Korea's Educational Broadcasting System (EBS) K-12 curriculum was established in 2004. The main purposes of the EBS curriculum launch were to cut per-household educational expenses, to supplement school education, and to ensure the internal stability of school education.

In the K-12 education phase, many countries have implemented open courseware (OCW) type approaches to address the problems of a conventional education curriculum (Butcher & Wilson-Strydom, 2008). Such approaches were meaningful in that students could access additional learning opportunities outside of the formal education system. At the same time, there was a limitation in the fact that the status of mainstream education would remain unchanged. In contrast, the South Korean central government launched the EBS K-12 e-learning programs so students could practice OER within the mainstream education curriculum. For instance, on the subject of 12th grade Korean language arts, EBS published 44 coursebooks in 2015, 34 coursebooks in 2014, 31 coursebooks in 2013, and 23 coursebooks in 2012. For the students, the EBS also provides video lectures (both streaming and download) for every single coursebook, online forums for discussions, and question-and-answer bulletins. For the Korean language arts teachers, the EBS provides a teacher edition of each coursebook, with extra notes. With these efforts, over the last decade, the average number of users per a day is 524,400 (Ministry of Education South Korea, 2016). Figure 1 reveals that there has been a steady increase in the number of users of EBS resources since 2007.

Figure 1. Number of EBS video lecture users, Ministry of Education South Korea (2016).

At the same time that OER are being adopted and implemented in many countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, South Africa, and India, one major drawback of OER is the quality problem (Jones, 2015; Wiley, Bliss, & McEwen, 2014). Quality problems may concern the two aspects of difficulties regarding OER: One is the difficulty of finding high quality material that can be of equal or greater usefulness and effectiveness than traditional resources, and the other is the difficulty of using OER to meet learning objectives. Therefore, it is important to examine how OER are represented in an integrated curriculum because these representations affect how a subject is taught in the classroom. Implied benefits and challenges can be identified by exploring how teachers respond to adopting an integrated curriculum including OER. Additionally, interrogating practices of teaching and learning based upon these integrated curriculums, including teachers' and students' views toward adopted OER, indicates how OER affect experiences of teaching and learning. Exploring views of teachers and students, classroom instructions, and EBS coursebooks, we argue that teachers and students in the Korean language arts classroom address two practical problems of OER: discovery and quality issues. In addressing these issues, teachers and students would get better teaching and learning experiences.

In this study, we look specifically at how teachers have adopted and adapted OER (EBS resources) in their classroom, and how students have responded to the implementation of OER. Due to the EBS curriculum's power to greatly influence classroom instruction, investigating practices of teaching and learning in the classroom is essential for ensuring Korean students are engaged in meaningful learning experiences. The following questions guided this study in order to identify benefits and challenges in adoption and adaptation of OER:

I begin the next section by illustrating the rationale of the ethnographic method for this study, particularly focusing on the Korean context. This discussion further explores how classroom ethnography would be an appropriate way of investigating the Korean high school classroom context. The findings of this research will extend our knowledge of OER in K-12 education. We also examine the benefits and challenges of teaching and learning using OER for constructing a new understanding of OER within the formal education curriculum.

This study falls within the line of inquiry established by Newell (Newell & Connors, 2011; Newell, VanDerHeide, & Olsen, 2014), conducting ethnographic study of high school classrooms. Van Maanen (2011) uses the term "ethnography" to refer to "documents that pose questions at the margins between two cultures" (p. 4). For Van Maanen, ethnography should seek understanding of different cultures.

Any classroom, of course, has its own culture, since teachers, students, and school curriculums are intertwined. For instance, when different teachers teach Macbeth to the same grade students, the cultures shaped by different teachers would be different according to teachers' teaching philosophies, approaches, concerns, ways of communication, and rapport. From the perspective of teachers, even when they rely on the same method of teaching literature and choose to use exactly the same teaching plans, they often experience different cultures according to different classrooms or student populations. In that case, what is ethnography and ethnographic research?

When it comes to the classroom context, classroom ethnography has been used to refer to a research practice of observing events in the classroom and of describing them fully. From this perspective, an ethnographer observes a teacher's instruction, student responses, and interactions between a teacher and students in the classroom for a more extended period of time than in other qualitative research such as case study. The roles of an ethnographer encompass these features:

Many researchers have a tacit awareness that hypothesis-testing or pre-to-post testing experiments is a scientific, rigorous, and high-level method, but qualitative observation, interviews, and analysis of language usage in daily life are often assumed as low-level method (Agar, 2013). This hierarchical misunderstanding has resulted in researchers adopting traditional science laboratory methods for their research: comparison between groups in simplified controlled settings. From the perspective of experimental methods, a researcher wants to test the hypothesis like all scientific research.

The problem is that our lives, teaching, and learning do not occur in isolated, decontextualized, or laboratory conditions. Within a traditional research setting, a researcher usually focuses on several variables to figure out their inter-relationships or cause-and-effect. Yet, in a real-life situations, outside of experimental conditions, there are many factors that influence outcomes or effects, such as beliefs, desires, interpretations, and backgrounds (Smagorinsky, Rhym, & Moore, 2013). Agar (2013) is critical of the tendency of these research methods by stating, "What if you don't have a theory or a hypothesis? What if you just want to explore how the world works?" (p. 8).

In this way, one question that needs to be asked is how teachers and students respond to OER in real situations; that is, the context of the classroom. Drawing on the basic characteristics of classroom ethnography described above, in this article, we identify and discuss how three Korean language arts teachers teach students using EBS resources.

In this study, we focus on the South Korean education system. This system has recently attracted renewed interest among politicians, researchers, and teachers around the world because students' academic performance has been evaluated by international large scale assessments. For example, according to the 2009 and 2012 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) results, Korean students rank second and fifth in reading among OECD countries, and Korea ranks first in PISA measures of educational equity (Areepattamannil & Caleon, 2013; Page, 2015). As a result, many organizations and leaders, including then-U.S. President Obama, have praised Korea for its successful educational system. A considerable amount of educational studies have also investigated Korean educational systems (e.g., Bozkurt, 2014; Byun, Schofer, & Kim, 2012; Cheung, Sit, Soh, Ieong, & Mak, 2014; Sánchez, Salinas, & Harris, 2011).

Education has been identified as a driving force of South Korea's rapid economic growth from a devastatingly poverty-stricken country to a leading information and communication technology (ICT) country (Lee, 2003). In particular, the Korean government has invested heavily in technology in education to encourage much more effective teaching and learning in secondary education. Consequently, since 2005, open educational resources (OER), including the EBS coursebooks and open courseware have played a key role in K-12 education in South Korea. Further, the Korean Ministry of Education established and enforced a new EBS educational policy stipulating that more than 70% of problems in Korea's College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) were taken from EBS coursebooks. CSAT is a standardized test accepted by Korean universities and is offered once a year. As the CSAT score plays a key role in determining which university will accept the student, this new EBS policy has exercised a great influence on the landscape of high school classrooms. This investment and the policy were launched as an effort to address the excessive private education market. Considering this Korean context of active adoption of OER in formal education, the exploration of the physical place—the Korean high school classroom—should be of interest to educators in other countries as well as researchers involved in OER in education.

For a decade, a large number of researchers have examined OER; all the studies reviewed so far, however, suffer from the fact that there is a degree of uncertainty around the terminology in "OER." The term "OER" was coined in the Forum on the Impact of Open Courseware for Higher Education in Developing Countries in 2002. The term "OER" was suggested and adopted to describe the new education model:

The open provision of educational resources, enabled by information and communication technologies, for consultation, use and adaptation by a community of users for non-commercial purposes. (UNESCO, 2002, p. 24)

OER have become a commonly-used concept in education since 2002 and even though many other researchers have offered definitions, it remains a difficult concept to precisely define (Wiley et al., 2014). Again, OER were described as "any educational resources... that are openly available for use by educators and students, without an accompanying need to pay royalties or license fees" (UNESCO, 2015, p. 5). Sometimes, the terms open courseware (OCW) and OER are used interchangeably, but OCW was defined by the OCW Consortium as "a free and open digital publication of high quality university-level educational materials." Although OER can support OCW, the two are not the same in that OER is a more overarching term, encompassing not only university but also elementary and secondary levels.

In this study, the term OER is used in its broadest sense to refer to all educational materials that are available free of cost and that exist in the public domain; for example, open textbooks, open courseware, and other open educational products. To be more specific, we will discuss how teachers and students adopt and adapt EBS coursebooks and lectures for their instruction in Korean language arts classes.

A great deal of previous research into OER has identified their positive effect on education. There are two main types of benefits of OER: quicker course development and education quality improvement. Adoption and adaptation of OER in education repeatedly results in making the course development faster than the traditional development process (Caudill, 2011; Wiley et al., 2014). Pitt (2015) reports that most educators in surveys had positive experiences with OER as a result of the effectiveness of high quality resources in strengthening their teaching practices. Likewise, a number of authors have showed that OER increase the effectiveness of education by saving costs for resources and by making instructional plans easier. Yet, Mtebe and Raisamo (2014a) point out that positive effects on education are not happening simply by adopting OER, but rather that this would come along with careful planning in advance. Without instructors' understanding and careful orchestration, OER are just another form of educational resources and would end up failing to change the current status quo. The problem is that most teachers have no knowledge of how to adopt and adapt OER in order to incorporate them into their instructions.

Nowadays, the EBS provides open educational resources at various levels by using different technologies including one-to-one academic coaching, mobile and smartphone applications, and an educator resource centre. Although BBC2 in the United Kingdom, PBS in the United States, TVO in Canada, and NHK2 in Japan all broadcast educational content, PBS and TVO broadcast educational animation mainly for children and NHK is also usually producing educational programs aimed at elementary and middle school level (Kim, 2014). The principal difference is that the EBS puts much more emphasis on OER at high school level; specifically, in 2015, 56 online courses were produced only for 12th grade Korean language arts. Each online course is made up of a series of video streaming around thirty to sixty hours, a coursebook, and an online platform for discussion and feedback.

One of the most significant barriers for long-term OER projects are financial difficulties (Annand, 2015; Butcher & Wilson-Strydom, 2008). The lack of business model is pointed out as a main weakness of OER (Downes, 2007; Hylén, 2006; Wiley et al., 2014). Against this backdrop, there are compelling examples of successful OER projects. For instance, OpenStax CNX by Rice University, Open.Michigan by the University of Michigan, and the Open Education Consortium at MIT are often referred to as successful OER projects. So far, however, very little attention has been paid to the role of OER at secondary level. On the other hand, the EBS had a turnover of US$100 million in 2012 and its net profit from 2010 to 2012 reached US$60 million (Kim, 2013; Lee, Kim, & Jeong, 2015). This is primarily because EBS coursebooks are provided both in PDF and hardcopy formats; users could download them online while students who prefer to use hardcopy for their study often chose to buy hardcopies for a reasonable price at bookstores.

Although many of the previous studies were conducted to investigate the correlation of OER in the classroom, previous published studies have only focused on the contexts of the United States (e.g., Kelly, 2014; Pitt, 2015; Yuan & Recker, 2015), United Kingdom (e.g., Bell, 2011; Connolly, 2013), Canada (e.g., Ives & Pringle, 2013; McGreal, Anderson, & Conrad, 2015; McKerlich, Ives, & McGreal, 2013), India (e.g., Khanna & Basak, 2013; Kumar, 2009; Panda, 2011), and South Africa (e.g., Mtebe & Raisamo, 2014a, 2014b; Prasad & Usagawa, 2014). In addition to the problem of the narrow scope of prior research contexts, as explained earlier in previous section, Context of Investigation: South Korea, it is true that there are several recent studies investigating the Korean educational system because of Korean students' high performance. However, these studies fail to give sufficient consideration to the experience and voices of classroom teachers and students. The main weakness with previous research on Korean education is that most attempted to analyze policy documents or used quantitative methods to examine Korean context.

While uncertainty still exists about how educators may use OER differently worldwide, this article reports on a study that addressed these constraints through a mixed-method approach with an ethnographic lens. This study enabled in-depth examination of the use of OER in the Korean high school classroom. Therefore, it provides new insights into OER research by filling a gap in the literature.

The first author visited Korean language arts classes to recruit participants—three Korean language arts teachers and 129 students. Students were enrolled in 12th grade Korean language arts courses. Wentworth High School (pseudonym) has a reputation for academic excellence in Seoul, the capital city of South Korea. Three teachers—Ms. Lee, Mr. Kim, and Ms. Park—taught 12th grade Korean language arts classes. The majority of students in three classes were expected to go to universities. See Table 1 for the participants' profiles; all names are pseudonyms.

Table 1

Information about Case Study Teachers

| Name | Ethnicity/Race | Grade level | Course | Educational background |

| Mr. Kim | Korean | 12th | Korean language arts | MA in Koreanlanguage arts education |

| Ms. Lee | Korean | 12th | Korean language arts | BA in Korean language arts education |

| Ms. Park | Korean | 12th | Korean language arts | MA in Korean language arts education |

Using ethnographic-oriented methods, we observed each of the three teachers teaching their Korean language arts classes from 2014 to 2015. The application of an ethnographic lens to our methodology inevitably brings these issues closer. In particular, as an ethnographer, working with, rather than testing, students, we tried to establish intimacy that is not available to quantitative or other kinds of researchers. We wrote field notes, created audio recordings of instruction based on OER, and collected teaching materials (e.g., copies of EBS coursebook pages and worksheets).

After observing each class session, we wrote reflective memos to add details to the field notes written during the observation and to reflect on insights about theoretical issues. To avoid misinterpretation of participants' performance, we tried to capture the participants' whole process within the learner's community, the classrooms, instead of simplified controlled settings (Vygotsky, 1978, 1934/1987). We also interviewed the teachers and students to more fully grasp their views toward an OER-integrated curriculum by drawing on Smagorinsky et al.'s (2013) interview questions. We were able to interview the teachers both formally and informally according to their interests, availability, and time. In other words, many of the interviews with teachers were closer to conversations among colleagues rather than formal interviews with a stranger.

Data analysis was an iterative process conducted alongside data collection. The data from field notes, recordings, and interviews were analyzed by drawing on Vygotsky's (1978, 1934/1987) views on the social nature of human activity. From a Vygotskian perspective, data are "social constructs" established through the relationship of research context, participants, and researcher (Smagorinsky, 1995; Newell et al., 2014). The goal of data analysis was to identify salient patterns of characteristics regarding use of the EBS with our developing understanding of the classroom context. Through this data analysis process, we contextualized our developing understanding of the use of the EBS in the classroom context.

Table 2

Summary of Collected Data and Analyses

| Teacher | |

| Sources of data | Focus of analysis |

| Initial interview (N=1) | Intellectual biography Purposes for teaching Korean/language arts |

| Retrospective interview (N=1) | Perceptions of field experience settings Adaptation of teaching tools from EBS as OER |

| Classroom observations (N=15; 750 min.) | Uses of EBS resources Social context of teaching |

| Post-observation debriefings (N=3) | Decisions during teaching Self-evaluation of lessons |

| Artifacts (e.g., lesson plans, instructional materials, and EBS coursebooks) | Evidence for planning Evidence for use of EBS resources |

| Curriculum documents | Conceptions of teaching and learning Sources of influence on instructional decisions |

| Student | |

| Sources of data | Focus of analysis |

| Questionnaires (N=129) | Perceptions of OER for teaching and learning |

| Retrospective interview (N=5) | Exploration of learning experience |

Figure 2. Pre-observation interview. (Source: From Smagorinsky et al.'s (2013) interview questions).

Figure 3. Post-observation interview. (Source: From Smagorinsky et al.'s (2013) interview questions).

Figure 4. Interview protocol for students. (Source: From Smagorinsky et al.'s (2013) interview questions).

Mr. Kim described good attributes of the EBS as involving good quality resources to use by emphasizing the fact that teachers can customize reading materials and worksheets easily through the user-friendly EBS website. Sometimes, he mentioned high expectations from students since many of them already watched online video lectures provided by the EBS before his class. As online video lectures usually deliver fixed sets of literary interpretation based on new criticism, Mr. Kim took a more comprehensive approach to teach reading comprehension and literature. Sometimes, he stated the key points for each topic like an EBS video lecturer. And besides, Mr. Kim explicitly explained ways of solving problems more quickly and easily in testing situations from the students' view in a way that was more effective than the EBS video lectures. This is an enhanced traditional approach, which gives opportunities for students to see how to solve problems and answer the questions more quickly and easily during high-stakes tests.

Ms. Lee preferred to promote student thinking rather than simply memorizing or restating what others [EBS coursebook authors] presented. She said, "I always encourage my students to share their ideas instead of conveying someone else's understanding unilaterally at the podium." When her class read Please Look After Mom, she said, the class divided into small groups, and students shared their ideas and discussed the same topic from the perspectives of different characters in the novel. Furthermore, she ran an activity-based class with creative writing, asking students to write in response to the protagonist following a certain event within the novel. This instruction often encouraged students to widen their views by considering different possibilities and interpretations between the lines. In this way, this instruction yielded high levels of interaction between teacher and students in the classroom. Her effort shaped her teaching belief and her own identity as a teacher: "I want to teach something beyond the teacher edition of textbooks and EBS coursebooks. I am not saying that guidelines for teachers in the teacher edition are not useful, but I want my students to try thinking differently, to look deeper."

Ms. Park relied more heavily on the content of EBS resources than the other two teachers. There are multiple resources designed by the EBS for teachers. Mr. Park stated, "EBS coursebooks and video lectures are made by famous language arts teachers who have been making various books and video lectures for students. They continuously revise EBS books and lectures every year so that they could reflect on students and teachers' responses." As there are plenty of video lectures by a number of language arts teachers, Ms. Park selected, and spent her spare time watching, a series of lectures by a teacher she thought would provide a good model for her instruction. In this way, she tried to fill a gap between EBS resources and her professional knowledge at the stage of planning her instruction.

On the whole, these results suggest that the use of EBS resources was helpful for teachers when orchestrating instructional plans. This is because the EBS provides teachers with various tools such as guidelines for teachers, slides, and basic forms of lesson plans, and then teachers relied on these resources to improve their instruction in classes even though the underlying driving factors are different.

Most teachers who made the EBS online video lectures are famous for their previous published books for students, for their prestigious educational backgrounds, and multiple experiences in educational fields. All these factors seem to be consistent with high quality EBS resources as OER. Ms. Lee, when asked, expressed the following belief:

Unlike many, I don't think all the content and teachers showed as great a quality as I could hope, but I would admit the fact that teachers in every region in this country are able to see how celebrated teachers teach the same concept by simply clicking a link on the EBS website. And this appears to lead to a better teaching quality in many classrooms because teachers could not help caring about EBS resources due to the fact that every student knows how other teachers teach the same subject.

Ms. Lee's belief, then, appears to suggest that distribution of EBS resources boosted the general level of teaching by functioning as the means of standard. However, she did not see the EBS teachers as a sort of threat to her authority. Yet, one unanticipated finding was that the high quality of these EBS teachers' performance might become a threat to the teacher's authority. Talking about this issue, Ms. Park said:

This is not the EBS teachers' fault, but I feel uncomfortable when students ask a question to me by referring to one of the popular EBS language arts lectures. When it comes to subject knowledge, students occasionally seem to trust the teacher in online video lecture more than me. Most EBS teachers are the kind of people who graduated from top schools, really going places, and haven't looked back. I appreciated the EBS resources, but it feels like I am never going to win the competition.

Although, another teacher, Mr. Kim, did not refer to the EBS courses specifically, he expressed an awareness that the existence of EBS resources and lectures might shape his teaching plans repeatedly by stating, "They [EBS teachers] also made many mistakes, and I often fixed both obvious and trifling errors of them during my class because students heavily rely on EBS coursebooks." As detailed in the previous section, Discovery and Quality, Mr. Kim's instruction focused on a compromised method of covering one single fixed answer and various ways of interpreting a certain concept through teacher-centered instruction. Each of his instructions involved a much more detailed explanation, compared with EBS lectures.

Consequently, Mr. Kim's teaching approaches positively re-asserted his authority as a teacher since students came to prefer Mr. Kim's instruction for his practical and detailed illustration over EBS video lectures. Regarding teachers' authorities, Mr. Kim said, "I did not intend to apportion blame for their [EBS teachers] mistakes as we all make mistakes. But I don't think they are special and distinct from us even though some language arts teachers tend to look up to them or even feel overwhelmed for EBS teachers' impressive academic backgrounds."

Overall, these results indicate that teachers' authorities are re-asserted implicitly and may become a scapegoat by student preferences, EBS teachers' prestigious educational background, and teachers' own ironic awareness of the high quality of EBS resources.

Meanwhile, the high quality of EBS resources imposes high expectations. As students can watch video lectures in advance, they often know ways of teaching a certain topic and concept to students before the lesson. This formed such a demanding atmosphere, Ms. Park said, that "it really pushed me to work hard to prepare instructional plans, because if I say something different from video lectures, students ask about this right away." She continued, "EBS coursebooks and lectures are great in that teachers and students can use various educational sources, but from the perspective of a teacher, I felt it as an additional responsibility or new pressure." EBS resources function as one of several key influences on instructional plans for the rest of teachers, Mr. Kim and Ms. Lee. In particular, Mr. Kim commented, "I didn't necessarily work as hard if EBS did not have an OER that had been zealously pushed forward by the government." He understood that more well-orchestrated instructional plans are required to meet his students' increasing needs stemming from learning the subject through EBS video lectures and coursebooks. Students' perceptions of EBS resources by questionnaires are below.

Table 3

Means and Standard Deviations of Students' Perceived Helpfulness of Ways of Learning Language Arts Subject (1 = very unhelpful, 4 = very helpful)

| N | Mean | SD | ||

| Valid | Missing | |||

| Group discussion of sample or problems | 129 | 0 | 3.19 | 0.69 |

| Teacher explains EBS course book | 129 | 0 | 2.93 | 0.78 |

| Studying language arts outside of class (i.e., as shadow education based on EBS) | 129 | 0 | 3.09 | 0.69 |

| EBS online video lectures | 129 | 0 | 2.98 | 0.81 |

| Study with other types of materials (not EBS resources) | 129 | 0 | 2.81 | 0.82 |

Despite the fact that some students perceived EBS resources on Korean language arts as challenging, nearly 92% of the students perceived learning language arts through EBS resources in the classroom as at least somewhat beneficial. In addition, through retrospective interviews, focal students described how their learning through the EBS affected their understanding of the Korean language arts subject. "I felt EBS video lectures are more effective in learning mainly because of their well-structured plans and EBS teachers' professional knowledge," one of interviewees, student A, said. She believed that "EBS teachers are different... even though both school teachers and EBS teachers use the same EBS coursebook." This view was echoed by other interviewees (students B, C, and E). "At the end of the semester, school teachers tend to rush in to finish progress or jump several chapters. But EBS teachers usually teach every page at a steady pace. I don't know why this happens repeatedly," student C stated.

The results of questionnaires indicate students' positive perceptions toward EBS resources. However, if we now turn to interviews with students, it reveals their preference for EBS teachers, which triggers an issue of teachers' authorities as we discussed above. In summary, these results show that the high quality of EBS resources has raised the expected level of teaching quality. The next section, therefore, moves on to discuss not only the benefits but also the challenges of OER in the Korean context, and we will also examine what this study adds.

Three teachers we investigated took different stances in relation to the integration of OER into their instruction: Mr. Kim prepared his teaching lessons to exceed the overall quality of EBS video lectures on the same topic to attract students' attention; Ms. Lee focused on the rich interactions between teacher and student or among students to provide a differentiated lesson that cannot be fulfilled via online video lectures; and Ms. Park endeavored to watch and learn how prominent teachers delivered a lecture to the same grade students. Although these three teachers took different approaches to integrating OER into their teaching practices, the underlying driving forces behind these changes were the adoption and adaptation of OER into their instructions. An implication of this educational improvement is the possibility that integration of OER into the formal educational curriculum improves the quality of classroom instruction by raising the bar.

As the findings demonstrate, all three teachers faced some threats to their authority as a teacher in the classroom due to EBS teachers' high quality lectures. The case presented here reconfirms Knox's (2014) finding that the authority of a teacher was simultaneously re-asserted and questioned when OER were introduced. In addition, Ms. Park's struggle to maintain her teacher authority reaffirmed the concern: how can less prestigious institutions compete with the world's most prestigious ones (Holford, Jarvis, Milana, Waller, & Webb, 2014)? Further, how can positive effects can be maintained simply adopting OER, without careful planning in advance (Mtebe & Raisamo, 2014a)? A possible answer to these questions also emerges from the analysis of the fact that two teachers, Mr. Kim and Ms. Lee, successfully developed their own instructions integrating OER.

Of course, these two teachers' cases above cannot fully illustrate the complex nature of the integration of OER in formal K-12 education. This is because of the myriad factors influencing each classroom: each individual teacher's teaching philosophy, professional knowledge, students, policy, and curriculum. To be more exact, these two teachers figured out how to handle OER individually, on their own, with no outside help. To better recognize and maximize the use of OER, however, professional development and teacher education would benefit from multiple opportunities to consider theoretical foundations and practical implications for contextualization. In short, both re-educating experienced teachers and preparing new teachers should complement ways of adopting and adapting OER to reflect on newer demands to promptly meet the needs of the times. As I illustrated in the previous section, without knowledge of how to use OER, the tool will not be effective as we could expect.

Because of a well-organized EBS database system—"the discovery problem"—the difficulty of finding educational resources (Wiley et al., 2014) is adequately addressed. Search services by grades, level of difficulty, and segmented topics have been created to help students and teachers to find OER more easily according to the individual's situation. For instance, students could watch only the small portion of a video lecture covering a certain part by entering a coursebook page or a question number. The "quality problem" of OER (Lee, Lin, & Bonk, 2007), is also addressed by governmental investment, diversified coursebooks, and prominent teachers' high performances in video lectures. In retrospect, one interviewee, student D, remarked that:

This was a fascinating opportunity to view different teachers' teaching methods about the same topic and concept. I remember thinking that I was unprepared for 12th grade Korean language arts subject, but I could choose the "right" coursebook and a video lecturer for me to catch up with the class. I absolutely did not think of teachers in my school as inferior to EBS teachers, but rather that EBS resources would be a great channel for bridging the gap by individualizing for myself, not to mention saving costs for shadow education.

Her reflection confirms our interpretation that the EBS as OER demonstrates one way to succeed in school from the student's perspective. However, re-contextualization of EBS content for the particular classroom continues to be a demanding challenge for teachers, educators, and researchers. This struggle is important to acknowledge and address because appropriate adaptation increases the usefulness of OER (Geith & Vignare, 2008; Willems & Bossu, 2012).

All three teachers struggled with OER, at least somewhat. Although teachers are aware of the possibilities of OER, they may have no knowledge of how to adopt and adapt OER into their conventional practice of teaching. We do not simply parade educational philosophies, pedagogies, and teaching strategies to preservice teachers during teacher education. Likewise, we do not ask preservice teachers to pick up and make a convenience of such concepts after having simply paraded various ideas. We do try to teach preservice teachers to grasp how these philosophies, pedagogies, and strategies interrelate with one another and how each idea was constructed in social and disciplinary contexts.

We are not arguing that OER in the Korean context is meaningless. Instead, we argue for a more complex view of adoption and adaptation of OER as both teachers' interpretation and as a discursive social practice. We reject the tacit assumption that teachers would pick up and use OER as if OER are additional texts or books teachers are already familiar with. We argue that what is evident from this empirical study is that it is pedagogical reflection and re-education that are absent but that are actually most required and need to be embedded in teaching and learning principles that maximize the usefulness of OER. Without a knowledge of OER, teachers would choose whatever OER with no reflection on their choice. The problem is, without reflection, OER would remain just one of many marginal educational resources.

This article has sought to apply an ethnographic lens to the research process to more fully understand and describe the use of OER in the Korean high school classroom. This has allowed me to explore aspects of my research practice that may have otherwise been overlooked or taken for granted. An ethnographic perspective has facilitated an underlying analysis of the benefits, challenges, and struggles of teachers and students with regard to the use of OER in formal educational curriculum.

The influences of OER that our participants identified include reduction not only of teachers' working time spent in designing teaching plans, but also of households' private education costs. Aside from these economic aspects, increased teaching qualities accompanying EBS resources, differentiated methods of teaching, and a flexible curriculum for students are revealed as positive effects of OER.

However, for the significance of appropriate use of OER, by adapting them, to be fully realized, we need to be concerned about how little attention is given when educating teachers to the subject of incorporating OER into instruction. Current concerns about the absence of any practical guidelines to help teachers adopt and adapt OER are in many respects concerns about the quality, effectiveness, and usefulness associated with OER. Bridging the gap between educational theories and practices, we will be constantly aware not only of the possibilities offered by OER, but also of the challenges they might pose to teachers and educators.

The key strengths of this study are its long period of classroom observation through an ethnographic lens and a thick description of the participants' views. This work contributes to existing knowledge of OER by assisting in our understanding of the effects of OER in K-12 education in the Korean context. A limitation of this study is the scope of this research. The scope of this study was limited in terms of the context of investigation, South Korea. The generalizability of these results might be subject to this research context. Notwithstanding this limitation, the study suggests that more research using ethnographic perspectives is needed to determine the efficacy of OER in K-12 education to better understand OER. Accordingly, further research could usefully explore how teachers and students in different countries adopt and adapt OER in their teaching and learning. More information on OER in K-12 education would help us to establish a greater degree of accuracy on this matter.

Agar, M. (2013). The lively science: Remodeling human social research. Minneapolis, MN: Mill City Press.

Annand, D. (2015). Developing a sustainable financial model in higher education for open educational resources. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(5), 1-15.

Areepattamannil, S., & Caleon, I. S. (2013). Relationships of cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies to mathematics achievement in four high-performing East Asian education systems. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 174(6), 696-702.

Bell, F. (2011). Connectivism: Its place in theory-informed research and innovation in technology-enabled learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(3), 98-118.

Bozkurt, B. Ü. (2014). Development of reading literacy in South Korea from PISA 2000 to PISA 2009. Education and Science, 39(173), 140-154.

Butcher, N., & Wilson-Strydom, M. (2008). Technology and open learning: The potential of open education resources for K-12 education. In Voogt, J., & Knezek, G. (Eds.), International handbook of information technology in primary and secondary education (pp. 725-745). New York, NY: Springer.

Byun, S. Y., Schofer, E., & Kim, K. K. (2012). Revisiting the role of cultural capital in East Asian educational systems: The case of South Korea. Sociology of Education, 85(3), 219-239.

Caudill, J. (2011). Using OpenCourseWare to enhance on-campus educational programs. TCC Worldwide Online Conference Refereed Proceedings (pp. 43–47). Retrieved from http://etec.hawaii.edu/ proceedings/2011/

Cheung, K. C., Sit, P. S., Soh, K. C., Ieong, M. K., & Mak, S. K. (2014). Predicting academic resilience with reading engagement and demographic variables: Comparing Shanghai, Hong Kong, Korea, and Singapore from the PISA perspective. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23(4), 895-909.

Connolly, T. (2013). Visualization mapping approaches for developing and understanding OER. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(2), 129-155.

Downes, S. (2007). Models for sustainable open educational resources. Interdisciplinary Journal of Knowledge and Learning Objects, 3, 30-44.

Geith, C., & Vignare, K. (2008). Access to education with online learning and open educational resources: Can they close the gap? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(1), 105-126.

Holford, J., Jarvis, P., Milana, M., Waller, R., & Webb, S. (2014). The MOOC phenomenon: toward lifelong education for all? International Journal of Lifelong Education, 33(5), 569-572.

Hylén, J. (2006). Open educational resources: Opportunities and challenges. Proceedings of Open Education, 49-63.

Ives, C., & Pringle, M. M. (2013). Moving to open educational resources at Athabasca University: A case study. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(2), 1-13.

Jones, C. (2015). Networked learning and institutions. In Jones, C. Networked learning: an educational paradigm for the age of digital networks. (pp. 107-136). New York, NY: Springer.

Kelly, H. (2014). A path analysis of educator perceptions of open educational resources using the technology acceptance model. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2), 26-42.

Khanna, P., & Basak, P. C. (2013). An OER architecture framework: need and design. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(1), 65-83.

Kim, J. E. (2013, August 22). The Asia Economic Daily. Retrieved from http://www.asiae.co.kr/news/view.htm?idxno=2013082211414971525

Kim, Y. Y. (2014). Progress and Seeking for new ways of EBS Programs. Journal of Media and Education, 4(1), 9-25.

Knox, J. (2014). Digital culture clash: "massive" education in the E-learning and Digital Cultures MOOC. Distance Education, 35(2), 164-177.

Kumar, M. V. (2009). Open educational resources in India's national development. Open Learning, 24(1), 77-84.

Lee, H. A., Kim, Y. H., & Jeong, J. H. (2015). Research trends regarding Korea's Educational Broadcasting System (EBS) (1990-2015). The Journal of Korean Education, 42(2), 29-54.

Lee, M. M., Lin, M. F. G., & Bonk, C. J. (2007). OOPS, Turning MIT Opencourseware into Chinese: An analysis of a community of practice of global translators. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 8(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/viewArticle/463

Lee, S. M. (2003). South Korea: From the land of morning calm to ICT hotbed. The Academy of Management Executive, 17(2), 7-18.

McGreal, R., Anderson, T., & Conrad, D. (2015). Open educational resources in Canada 2015. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(5), 161-175.

McKerlich, R. C., Ives, C., & McGreal, R. (2013). Measuring use and creation of open educational resources in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(4), 90-103.

Ministry of Education South Korea (2016). The usage status of EBS learning resources. Retrieved from http://www.index.go.kr/potal/stts/idxMain/selectPoSttsIdxMainPrint.do?idx_cd=1560&board_cd=INDX_001#link

Mtebe, J. S., & Raisamo, R. (2014a). Challenges and instructors' intention to adopt and use open educational resources in higher education in Tanzania. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(1), 249-271.

Mtebe, J. S., & Raisamo, R. (2014b). Investigating perceived barriers to the use of open educational resources in higher education in Tanzania. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2), 43-66.

Newell, G. E., & Connors, S. P. (2011). "Why Do You Think That?" A supervisor's mediation of a preservice English teacher's understanding of instructional scaffolding. English Education, 43(3), 225-261.

Newell, G. E., VanDerHeide, J., & Olsen, A. W. (2014). High school English language arts teachers' argumentative epistemologies for teaching writing. Research in the Teaching of English, 49(2), 95-119.

Page, T. M. (2015). Common pressures, same results? Recent reforms in professional standards and competences in teacher education for secondary teachers in England, France and Germany. Journal of Education for Teaching, 41(2), 180-202.

Panda, S. (2011). Continuing education and lifelong learning in the Indian sub-continent: Critical reflections. International Journal of Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning, 4(1), 25-48.

Pitt, R. (2015). Mainstreaming open textbooks: Educator perspectives on the impact of openstax college open textbooks. The International Review of Research in Open And Distributed Learning, 16(4), 133-155.

Prasad, D., & Usagawa, T. (2014). Towards development of OER derived custom-built open textbooks: A baseline survey of university teachers at the University of the South Pacific. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(4), 226-247.

Sánchez, J., Salinas, Á., & Harris, J. (2011). Education with ICT in South Korea and Chile. International Journal of Educational Development, 31(2), 126-148.

Smagorinsky, P. (1995). The social construction of data: Methodological problems of investigating learning in the zone of proximal development. Review of educational research, 65(3), 191-212.

Smagorinsky, P., Rhym, D., & Moore, C. P. (2013). Competing centers of gravity: A beginning English teacher's socialization process within conflictual settings. English Education, 45(2), 147-183.

UNESCO. (2002). Forum on the impact of open courseware for higher education in developing countries: Final report. Retrieved from www.unesco.org/iiep/eng/focus/opensrc/PDF/OERForumFinal Report.pdf

UNESCO. (2015). A Basic Guide to Open Educational Resources (OER). Retrieved from unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002158/215804e.pdf

Van Maanen, J. (2011). Tales of the field: On writing ethnography (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In L. S. Vygotsky, Collected works (Vol. 1, pp. 39-285) (R. Rieber & A. Carton, Eds; N. Minick, Trans.). New York: Plenum. (Original work published 1934)

Wiley, D., Bliss, T. J., & McEwen, M. (2014). Open educational resources: A review of the literature. In Spector J. et al. (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 781-789). New York, NY: Springer.

Willems, J., & Bossu, C. (2012). Equity considerations for open educational resources in the globalization of education. Distance Education, 33(2), 185-199.

Yuan, M., & Recker, M. (2015). Not all rubrics are equal: A review of rubrics for evaluating the quality of open educational resources. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(5), 16-38.

How Korean Language Arts Teachers Adopt and Adapt Open Educational Resources: A Study of Teachers' and Students' Perspectives by SuBeom Kwak is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.