|

Pumela Msweli

University of South Africa

Open distance learning is viewed as a system of learning that blends student support, curriculum and instruction design, flexibility of learning provision, removal of barriers to access, credit of prior learning, and other academic activities such as programme delivery and assessment for the purpose of meeting the diverse needs of students. Internationalisation, on the other hand, is viewed as a process that blends intercultural international dimensions into different academic activities, such as teaching, learning, and research, into the purpose and functions of higher education. The common feature in the narratives that define open distance learning and internationalisation is the blending of university services to achieve specific outcomes. This blending feature has instigated an inquiry into identifying the interplay between the two concepts in as far as how the concepts are defined and what their goals and rationale are in the context of higher education institutions. While there are a breadth and variety of interpretations of the two concepts, there are differences and common features. The purpose of such an analysis is to open a new window through which institutions of higher learning can be viewed.

Keywords: Curriculum design; higher education institutions; South Africa; internationalisation; student support; teaching and learning

Both open distance learning (ODL) and internationalisation of higher education convey a variety of understandings, interpretations, and applications. For example, ODL is viewed as a system of meeting multiple and diverse learning needs of students through course design, administrative processes, and learner support (O’Rourke, 2009). Another view that is more nuanced towards promoting flexibility in learning provision is propounded by a number of scholars such as Braimoh (2003) and Sonnekus, Louw, and Wilson (2006). There is also a view of ODL that emphasises acquiring, creating, and sharing knowledge by interacting asynchronously or synchronously without the constraints of space and time (De Beer & Bezuidenhout, 2006; Monk, 2001; Littlejohn & Margaryan, 2010; De Beer, 2010; Heydenrych & Prinsloo, 2010). While these views are not necessarily mutually exclusive, they portray a system of learning that weaves together student support, curriculum and instructional design, and other academic activities such as programme delivery and assessment for the purpose of meeting the diverse needs of students.

It is not only the variety of interpretations that lend ODL comparable to internationalisation, but it is also the interplay between the meaning and definitions of these concepts, especially the blending or integrative characteristics of certain features of these concepts. For instance, a view of internationalisation as a process of integrating an international dimension into the research, teaching, and services function of higher education, as propounded by Knight (2004), depicts the blending feature in the process of internationalisation that is similar to one of the key features of ODL.

Internationalisation literature also presents divergent views about the dimensionality of the construct. For example, Krause, Coates, and James (2005) see internationalisation as a five-dimensional concept including (1) teaching and curriculum issues, (2) faculty, (3) research, (4) student issues, and (5) strategy; whereas Elkin, Farnsworth, and Templer (2008) present a nine-dimensional measure of internationalisation in their study that explores the relationship between strategy and the extent of externalisation. These include (1) undergraduate international students, (2) postgraduate international students, (3) student exchange programmes, (4) staff exchange programmes, (5) staff interaction in international contexts at international conferences, (6) internationally focused programmes of study, (7) international research collaboration, (8) support for international students, and (9) international institutional links.

The integrative feature of the concepts of internationalisation and ODL has raised a question of how the two concepts converge in a manner that enhances the outputs and outcomes of higher education. The purpose of this article is to map out the interplay between these two concepts, with a special focus on how the concepts are defined as well as on the goals and rationale of the two concepts. Shedding light on the interconnectedness of the concepts is likely to strengthen the ability of higher education institutions to design offerings and systems that are more customer focused. This discourse is organised into four parts. The first part paints in broad brush strokes the context of ODL and internationalisation in South Africa. The second part of the paper is an explication of the meaning and definition of the two concepts. The third part looks into the rationale and goals of the two concepts then maps out how the two concepts are related. This is followed by a discussion on implications for higher education institutions.

Globalisation has posed many challenges to the South African economy. The 2008 global economic downturn, which was characterised by a fall in gross domestic product (GDP) and severe job losses, is a clarion call for higher education institutions to create new global competencies. The message is quite clear: Those who are skilled will secure the benefits of the global economy and thrive in the 21st century. The pressure is mounting with the New Growth Path Framework (Patel, 2011) to seek ways of creating 5 million jobs by 2020. The compelling pressure from all angles has opened up a space in the higher education sector to interrogate the employability of graduates for the new economy. At the regional level, the Higher Education and Training protocol for the nations of Southern Africa calls for harmonisation of the regional education systems and stresses maintenance of acceptable quality standards (SAUVCA, 2004). The quality imperative is being driven at the national policy level and it is at this level where strong messages are being sent for internationalisation of education systems in the region. The Council on Higher Education (CHE, 2009) entrenches the idea of increasing recruitment of students from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) as a process of internationalisation. The outcome of attracting SADC students is not only to enrich the experience of South African students, but also to add to enrolment and graduation subsidies of host institutions (CHE, 2009).

In a comprehensive study on internationalisation in South Africa, McLellan (2008) argues for the importance of developing a broad framework for internationalisation that clarifies the government’s position on issues such as

Notwithstanding the lack of a framework that clarifies the government’s position, the CHE (2009) encourages South African institutions to engage with internationalisation because the country enjoys a leading position in research output and the number of foreign students it attracts to its shores in comparison to other African countries.

ODL is envisaged by the CHE (2009) to be the mechanism for opening access to people who would not have been able to study in face-to-face instructional situations or at a traditional institution. Out of the 23 public higher education institutions in South Africa, the highest proportion of enrolments (37.6%) in 2007 was in distance programmes (CHE, 2009). The 2004 merger between the University of South Africa, Technikon SA, and the distance learning element of Vista marked a significant development in distance and open education in South Africa (CHE, 2009). University of South Africa is the dominant player in the provision of distance education.

As suggested by Heydenrych and Prinsloo (2010) there is no homogeneity in terms when it comes to describing ODL. Heydenrych and Prinsloo (2010) point out that even though open distance learning is used interchangeably with distance learning, not all distance education institutions embrace ODL, but all ODL institutions offer distance education. The terms used to describe ODL have differed across different geographical areas and institutions. The Commonwealth of Learning suggests that there is no single phrase that captures the essence of ODL. The rather different approaches and different terms that can be used to describe the concept may include “learner-centred education, open learning, open access, flexible learning and distributed learning” (Commonwealth of Learning, 2000, p. 2). To elucidate the point about the variants of distance education, the Commonwealth of Learning maps out four scenarios for ODL and points out that most ODL institutions use a combination of the four scenarios.

Scenario 1 – Same time, same place: Classroom teaching, face-to-face tutorials, seminars, workshops, and residential schools

Scenario 2 – Same time, different place: Audio conferences and video conferences, television, one-way or two-way videos etc.

Scenario 3 – Different time, same place: Learning resource centres which learners visit at their leisure

Scenario 4 – Different time, different place: Home study, computer conferencing, tutorial support by e-mail and fax communication

Table 1 presents a sample of ODL definitions. The definition offered by the CHE (2009) seems to be comprehensive enough to include key elements of distance learning featured in most ODL literature: (1) learner centredness, (2) lifelong learning, (3) flexibility, (4) provision of learner support, and (5) removal of barriers to access. What makes the definition particularly relevant for South Africa is an addition of the recognition of prior learning (RPL) element which espouses a more inclusive approach to education. The principle of learner centredness in the CHE definition of ODL takes into account that learners come from different socioeconomic backgrounds with different needs that should be catered for in an open distance learning system.

A descriptive definition that portrays ODL from a European perspective was put forward by the Open and Distance Learning Quality Council of the European Association for Distance Learning (2010) as a form of learning that includes

any provision in which a significant element of the management of the provision is at the discretion of the learner, supported and facilitated by the provider. This ranges from traditional correspondence courses, on-line learning centres and face-to-face provision where a significant element of flexibility, self-study, and learning support, is integral to the provision.

The definition is descriptive because it not only provides an explanation of ODL, it also clarifies the application of the concept by describing the range of scenarios that providers can apply as an integral part of learning provision. As a matter of fact, the definition resonates with the four scenarios of ODL propounded by the Commonwealth of Learning (2000). The definition also makes it clear that ODL is a learner-centred approach to learning that requires the provider to use all institutional resources to ensure that a diverse range of learners’ needs are met.

Table 2 presents sample definitions of internationalisation in chronological order from 1977 to 2011. An analysis of internationalisation definitions suggests a convergence towards an idea that internationalisation is a process. Johanson and Vahlne’s (1977) study has been cited (see Galan, Galende, & Gonzalez-Benito, 1999) as having shaped the conceptualisation of internationalisation as a process, even though the study did not deal with universities specifically. Johanson and Vahlne (1977, p. 23) define internationalisation as a process of “…gradual acquisition, integration and use of knowledge about foreign markets and operations, and on the incrementally increasing commitments to foreign markets.” The process approach that Johanson and Vahlne (1977) propound views internationalisation as an “incrementally increasing commitment to foreign markets.” What differentiates Johanson and Vahlne’s definition from other definitions is that they specify the domain of the internationalisation process and posit a theory that explains how four specific variables, market knowledge, commitment decisions, current activities, and market commitment, interact to explain the internationalisation process.

Soderqvist’s (2007, p. 29) definition of internationalisation introduces a change process in the management of the internationalisation project in higher education institutions (HEIs):

The internationalisation of a higher-education institution is a change process from a national HEI into an international HEI leading to the inclusion of an international dimension in all aspects of its holistic management in order to enhance the quality of teaching and research and to achieve the desired competencies.

The change process is explained by a five-stage model that starts with the zero stage. According to Soderqvist (2007), the zero stage is characterised by marginal internationalisation activity. This stage is posited to be followed by the student mobility stage then curriculum and research; subsequent to that is the institutionalisation of internationalisation and commercialisation of the outcomes of internationalisation. Soderqvist’s conceptualisation of internationalisation espouses Johanson and Vahlne’s model of “incremental change” although nuanced towards enhancement of quality in teaching and research.

Ayoubi and Massoud (2007) view internationalisation as a process with three phases: (1) international strategy design phase, (2) implementation of the internationalisation process, and (3) evaluating the internationalisation strategy. The authors proceed to measure some aspects of internationalisation without providing conceptual definitions and details of how the items in the measures represent the domain of the constructs being measured.

Knight (1999) presents a different internationalisation process in her widely accepted definition of internationalisation. She states that internationalisation is “the process of integrating an international dimension into the research, teaching and services function of higher education.” Arguably, Knight’s decision (2004) to include the international, intercultural, or global dimensions in a modified definition of internationalisation was influenced by the emergence of the Internationalisation at Home project (Crowther, Joris, Nilsson, Teekens, & Wachter, 2000). Knight (2006) refers to the international, intercultural, and global dimensions as the “triad” of the internationalisation process. She defines internationalisation as the process that involves integrating the triad into the purpose, functions, or delivery of postsecondary education (Knight, 2004). In Europe, internationalisation has become a strategic issue as pointed out by Crowther (2000, p. 37) in this statement: “Internationalisation has become central to universities’ mission, and the focus is on ‘systemic internationalisation’ more than on mobility.”

Literature shows that internationalisation definitions have widened to include strategies on teaching and learning, quality assurance, governance, human resource development, and resource mobilisation (see Bartell, 2003; Soderqvist, 2007; Ayoubi & Massoud, 2007; Elkin, Farnsworth, & Templer, 2008; McLellan, 2008).

A number of internationalisation definitions offered by different authors illustrate the fact that, similar to ODL, there is not a single definition of internationalisation that satisfies all legitimate actions or applications of internationalisation. Scheffler (1960) suggests that when there is a myriad of definitions offered in literature, it is better to adopt a definition that suits a particular context. Following that line of argument, this study adopts the following definition of internationalisation: “Internationalisation is the extent to which an institution is strategically positioned to operate within an international and intercultural sphere through its academic activities” (Msweli, 2011, p. 14).

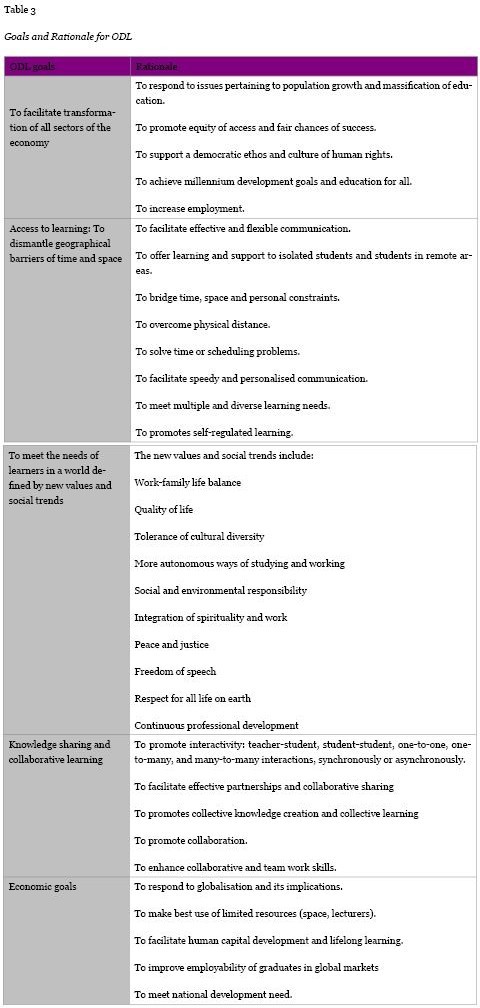

A careful look at the goals of ODL as depicted in Table 3 shows that ODL is a way of responding to a global environment characterised by significant political and socioeconomic trends as well as by technological advances. Undeniably, the most significant trend in the world is the rate of population growth. By 1960 the world population had reached 3 billion and almost doubled in 1974 with approximately 5.3 billion people (Hutchinson, 1996). According to the United States Census Bureau (2012) there are about 7.01 billion people in the world. The sharp rise in the number of people calls for more flexible ways of accessing education.

As pointed out by Banathy (1996), it is an ‘old story’ to attribute changes just to technology and globalisation. As environmental, socioeconomic, legislative, and ethical issues gain more prominence, the demands for governments to respond to the pressures of democratising economic institutions have increased. The dynamics of the new world environment requires institutions to embrace not only new technologies but new value systems in order to remain relevant and to survive in the global economic environment. Table 3 shows that ODL espouses the values of more autonomous ways of studying and working, accessible education for all, and continuous professional development.

Access to learning and the goal to meet the needs of learners are the two most prized goals of ODL. This is because ODL extends access to those who would have been excluded on the basis of physical distance, personal constraints, or because of full-time employment or family responsibilities. The goal of access is also identified as one of the key goals of the National Plan for Higher Education (Ministry of Education, 2001) in South Africa. Linked to the goal of access is the requirement to provide educational opportunities to “an expanding range of population irrespective of race, gender, age, creed or class or other forms of discrimination” (Ministry of Education, 2001). ODL has been recognised by a number of scholars as an effective way of increasing equity in education access (Braimoh, 2003; Sonnekus, Louw, & Wilson, 2006; De Beer & Bezuidenhout, 2006; Heydenrych & Prinsloo, 2010).

It is a widely accepted view amongst internationalisation scholars (De Wit, 2006; Knight, 2004; Soderqvist, 2007; McLellan, 2008) that there are four broad categories of rationale for internationalisation of higher education. However, the predominance of any one category may vary from country to country.

The GATS sets general rules and national schedules which list individual countries’ commitments to access to their domestic markets by foreign suppliers. As a result, universities all over the world are showing increasing interest in the potential for exporting education for economic benefit.

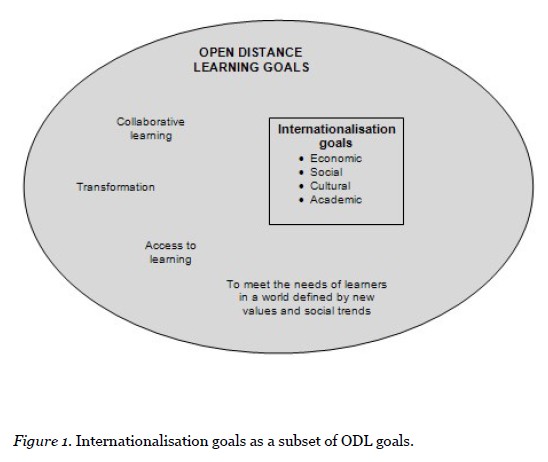

Similar to internationalisation, ODL is driven by economic, social, cultural, and academic values; however, ODL has a bigger range of goals, as illustrated in Figure 1. As Figure 1 shows, and as depicted by the definitions provided earlier, ODL is a system with multiple interrelated processes. Internationalisation is one such process in the dynamic ODL system.

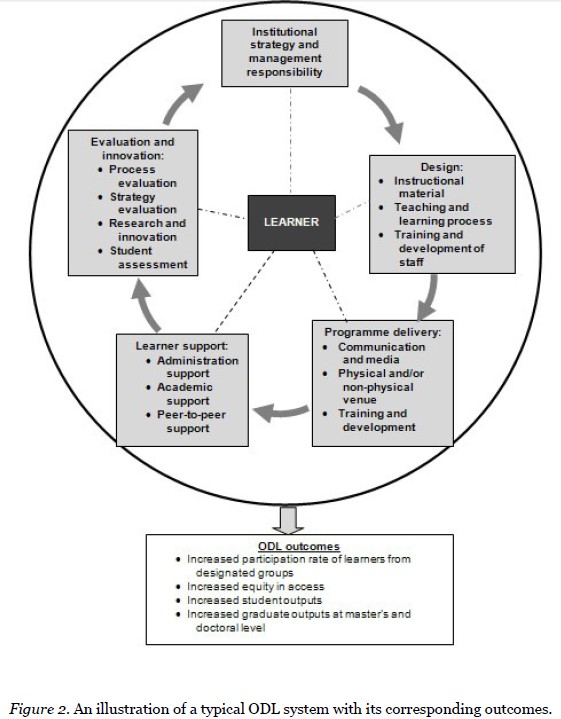

The metaphoric view of ODL as a system and internationalisation as a process provides an indication of how these concepts are related. The word system in the definition of ODL suggests that there are different components or variables that have to work together to achieve the goal of a system. On the other hand, the word process suggests a flow of activities in a sequence that could either be linear or dynamic. Hoyle (2009) provides a helpful framework explaining the distinction between system and process. He suggests that a process is ordinarily static and it delivers tangible outputs; whereas, a system is dynamic and produces outcomes (level of performance) that might be associated with a process or output. Figure 2 depicts a typical ODL system with different components as well as some of the desired outcomes of an ODL system.

As depicted in Figure 2, the ODL system is centred on meeting the needs of learners and the target market as would be identified in the strategic plan of an ODL institution. The illustration also shows that training and development is an integral part of the different components of the ODL system. The system is characterised by a continuous evaluation process that should inform strategy review processes.

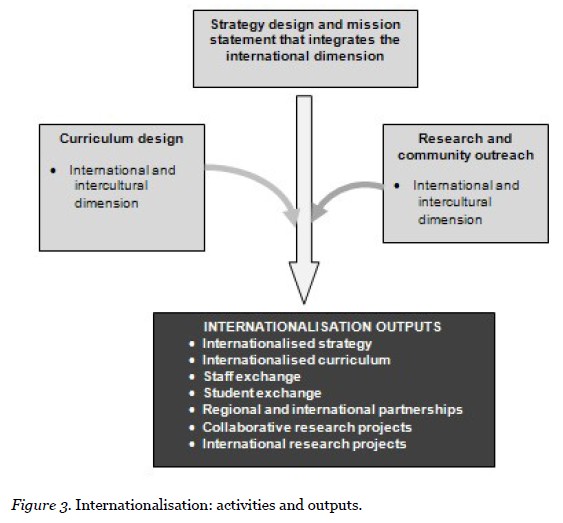

Figure 3 depicts the different activities of the internationalisation process and some of the desired outputs of internationalisation.

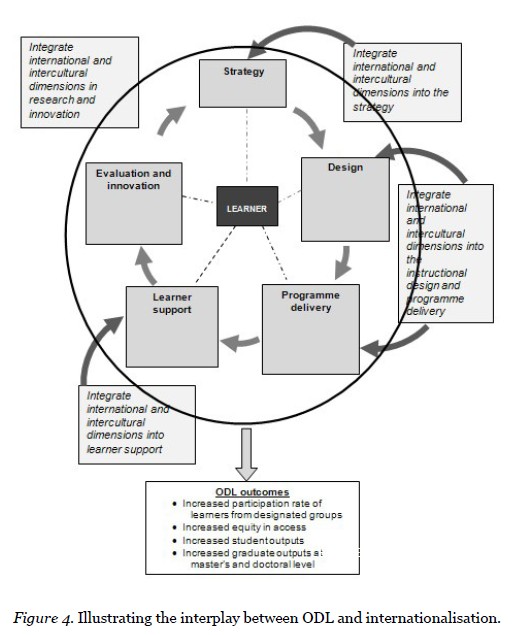

As Figure 3 shows, the key outputs derived from the internationalisation process include an internationalised strategy and curriculum, staff and student exchange, partnerships, and research collaborations. This paper posits that to fully realise the benefits of an ODL system, each component of the ODL system must be internationalised.

Figure 4 shows that each component of the ODL system can and should be internationalised to derive the full outcomes of ODL which include an expanded and equitable access to education and training and increased student outputs.

There are two significant contributions to knowledge that this study makes. Firstly, this study provides an exposition of how the rationale and goals of ODL converge with those of internationalisation. For example, in a higher education institution that embraces the ODL system, the ODL strategy of the institution shapes the different components and processes within the system and the manner in which resources are allocated. In such a scenario senior management works with different functions throughout the institution in the development of corresponding operational plans that deal with instructional material design, teaching, and learning strategy. Such strategies are informed by the learner needs and the outcomes that the institution seeks to achieve. This study suggests that the entire ODL system is dynamic rather than linear and is continuously informed by research and innovation.

The second contribution that this study makes is in showing that internationalisation is a process embedded in each component of the ODL system. The manner in which internationalisation is linked to ODL, as illustrated in Figure 4, suggests that internationalisation is as dynamic as ODL. As Figure 4 shows, there are internationalisation dimensions in each component of the ODL system. This study puts forward an argument that for an ODL institution to derive the fullest benefit of resources deployed to implement ODL it has to be perfectly internationalised at all levels. Arguably, all higher education institutions, whether they embrace distance learning or open distance learning, are national institutions operating in international spaces locally, regionally, and abroad. As such, internationalisation has to feature at the very least in the teaching, learning, and research processes of all higher learning institutions. Expanding on the same logic, an ODL institution that seeks to increase equitable access and to increase graduation rates of students who have relevant skills for the globalised world would want to ensure that all elements of the ODL system are internationalised.

Further research is needed, firstly, to look into the factors that explain each of the five components of the ODL system as delineated in Figure 2, and, secondly, to test the empirical validity of the proposition that a combination of internationalisation dimensions with components of ODL is likely to yield better outcomes in terms of equitable access, increased participation rates of students from designated groups, increased student outputs, and increased graduate outputs at master’s and doctoral levels. Although it is apparent that the distinction between ODL and internationalisation is somewhat diffused with respect to economic, social, and cultural rationales, it is critical to understand the process of internationalisation as it affects ODL institutions in South Africa. In South Africa, the higher education sector is still engaged in debates on how to internationalise while simultaneously dealing with local, regional, and global environmental factors shaping higher education. An opportunity exists for further research to explore the levels of internationalisation and how internationalisation is linked to the strategic focus of ODL institutions in South Africa.

The author thanks the editor and reviewers of IRRODL for their helpful comments, which have enhanced the quality of this paper.

Ayoubi, R.M., & Massoud, H.K. (2007). The strategy of internationalisation in universities – a quantitative evaluation of the intent and implementation in UK universities. International Journal of Educational Management, 21(4), 329-349.

Banathy, B.H. (1996). Designing social systems in a changing world. New York, Plenum.

Bartell, M. (2003). Internationalisation of universities: A university culture-based framework. Higher Education, 45(1), 43-70.

Braimoh, D. (2003). Transforming tertiary institutions for mass higher education through distance and open learning approaches in Africa: A telescopic view. South African Journal of Higher Education, 17(3), 13-25.

Commonwealth of Learning. (2000). An introduction to open and distance learning. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/resources/publications/trainingresources/Pages/intro.aspx

Council on Higher Education (CHE) (2009). The state of higher education in South Africa. Higher Education Monitor, 8 (October).

Crowther, P., Joris M., Nilsson B., Teekens, H., & Wachter B. (2000). Internationalisation at Home position paper. European Association for International Education.

Crowther, P. (2000). Internationalisation at home – institutional implications. In Internationalisation at Home position paper. European Association for International Education.

De Beer, K.J. (2010). Open and distance e-learning at the Central University of Technology. Progressio, 9(2), 41-58.

De Beer, K., & Bezuidenhout, J. (2006). A preliminary literature overview of open learning at the Central University of Technology, Free State, South Africa. Progressio, 28(1 & 2), 64-81.

De Wit, H. (2006). Changing dynamics in the internationalisation of higher education. In R. Kishun (Ed.), The internationalisation of higher education in South Africa (pp. 29-39). Durban: IEASA.

Elkin, G., Farnsworth, J., & Templer, A. (2008). Strategy and the internationalisation of universities. International Journal of Educational Management, 22(3), 239-250.

Galan, J.I., Galende, J., & Gonalez-Benito, J. (1999). Determinant factors of international development: Some empirical evidence. Management Decision, 37(10), 778-785.

Heydenrych, J.F., & Prinsloo, P. (2010). Revisiting the five generations of distance education: Quo vadis? Progressio, 32(1), 5-26.

Hoyle, D.D. (2009). Systems and processes – Is there a difference? Retrieved from http://www.thecqi.org/Documents/community/South%20Western/Wessex%20Branch/

Systems%20and%20Processes%20article%20by%20David%20Hoyle%20Oct09%20(2).pdf

Hutchinson, F. (1996). Educating beyond violent futures. Routledge: London.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm – a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23-32.

Knight, J. (2003). Internationalisation of higher education: Practices and priorities. International Association of Universities.

Knight, J. (2006). Internationalisation in the 21st century: Evolution and revolution. In R. Kishun (Ed.), The internationalisation of higher education in South Africa (pp. 41-58). Durban: IEASA.

Krause, K., Coates, H., & James, R. (2005). Monitoring the internationalisation of higher education: Are there useful quantitative performance indicators? International Perspectives on Higher Education Research, 3, 233-253.

Littlejohn, A. (2011). Change 11 position paper: Connected learning, collective learning. Retrieved from http://littlebylittlejohn.com/change11-position-paper/

Littlejohn, A., & Margaryan, A. (2010). Sharing resources in educational communities. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 5(2). Doi:10.3001/ijet.v5i2.857.

McLellan, C.E. (2008). Speaking of internationalisation: An analysis policy of discourses on internationalisation of higher education in post-apartheid South Africa. Journal of Studies in International Education, 12(2), 131-147.

Ministry of Education. (2001). National plan for higher education in South Africa. Pretoria.

Monk, D. (2001). Open/distance learning in the United Kingdom. Why do people do it here (and elsewhere)? Perspective in Education, 19(3), 53-65.

Msweli, P. (2011, August/September). Internationalisation in higher education institutions in South Africa: Scale development and measurement. Paper presented at 15th Annual IEASA Conference, Durban.

Open and Distance Learning Quality Council. (2010). Open and distance learning – a formal definition. Retrieved from http://www.odlqc.org.uk/odl.htm

O’Rourke, J. (2009). Meeting diverse learning needs. Progressio, 31(1 & 2), 5-16.

Patel E. (2011). The New Growth Path: The framework. Retrieved from http://www.info.gov.za/view/DownloadFileAction?id=135748

Smout, M (Ed.) (2003). Internationalisation and quality in South African universities. South African Universities' Vice-Chancellors' Association (SAUVCA).

Soderqvist, M. (2007). Internationalisation and its management at higher-education institutions – applying conceptual, content and discourse analysis. Helsinki: Helsinki School of Economics.

Sonnekus, P., Louw, W., & Wilson, H. (2006). Emergent learner support at University of South Africa: An informal report. Progressio, 28(1 & 20), 44-53.

Swanepoel, E., De Beer, A., & Muller, H. (2009). Using satellite classes to optimise access to and participation in first-year business management: A case at an open and distance-learning university in South Africa. Perspectives in Education, 27(3), September, 311-319.

United States Census Bureau (2012). US & world population clocks. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/main/www/popclock.html

United States Distance Learning Association. (2010). Home. Retrieved from http://www.usdla.org/

Wächter, B. (2000). Internationalisation at home – the context. Internationalisation at Home position paper. European Association for International Education.